At 3AM, I landed and found my grandpa sitting alone at the airport gate — shivering, confused, and holding an empty envelope. He told me my parents had “just dropped him off after signing some papers.” Those papers turned out to be the deed to his house.

Part I — Gate 12

The terminal’s fluorescent hum always makes time feel flatter than it is. Even so, I knew it was 3 a.m. because the digital clock above Gate 12 coughed its seconds into the chill air as if they were something you could inhale. That was where I found him: hat crooked, golf shirt too thin, hands tremoring in the conditioned cold. Walt Morton. Seventy-eight. My grandfather.

“Grandpa,” I said softly.

He blinked, surfacing. “Clare?”

I wrapped my jacket around his shoulders, the one with police stitched discreetly inside. His skin felt like winter glass. His suitcase sat between his shoes like a tired dog. The manila envelope in his lap was stamped in thick black ink: deed transfer.

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

He tried a smile and failed halfway. “Your folks dropped me after supper,” he said. “Said it would be easier if I waited. For the flight. After I signed the papers.”

“What papers?”

“You know,” he said, wobbling the words. “The house.”

We were in a sleeping airport in a country that never sleeps. Somewhere two gates down a baby hiccuped. A floor polisher made one quiet pass like a custodian erasing footprints. A gate agent tilted his head in our direction, then looked away, embarrassed by his own curiosity. I sat beside Grandpa and took his hand.

“Tell me exactly what happened.”

“They said refinancing would help with bills,” he said. “Said I’d sign and they’d handle everything. Afterward, your dad drove, your mom carried the envelope, and we came here. ‘We’ll be right back, Pop,’ they said.” He looked at the empty concourse and managed a fraction of a laugh. “Been coming back ever since.”

“How long?”

“Since supper,” he said. “I think.”

Training flickered through me—checklists and triage from a different uniform. Indicators: sudden property changes, medication gatekeeping, isolation. I didn’t need the checklist to smell the wrong. I needed facts.

“Do you have your meds with you?” I asked, voice low and calm, the way you keep people safe with your tone before you can with your actions.

“In the kitchen,” he said. “Lisa sorts them. I get confused.”

“Right now,” I said, “you’re just cold and tired.”

He nodded and tried to straighten the envelope. It sagged, empty.

“I’ll get coffee,” I said. He shook his head.

“Bring the kind your grandma used to make.”

“They don’t sell that here,” I said, and he chuckled, a sound that broke clean through my anger.

The kiosk was a rectangle of stale muffins and humming urns. I bought two paper cups and a wrapped shortbread—Grandma always had those in the pantry for emergencies, which is what she called company. I stirred his cream the way she did: slow circles, so she could say she could taste the care. When I came back, he was watching the runway like a fisherman reads water for weather.

I laid my scarf across his knees, handed him the coffee, and slipped the envelope into my backpack without making a ceremony of it. The speakers coughed a warning about unattended baggage. Maintenance traced slow arcs with a buffer. I ordered a car. My phone vibrated with a dread that had shape: eighteen missed calls from my father; a nineteenth blinking as I stared. I put the phone away.

“Where are we going?” Grandpa asked.

“Home,” I said. “Mine.”

“To your apartment?” he asked.

“To somewhere that isn’t empty.”

When we stood, his knee complained. I slid an arm around him. The jacket was warm on his shoulders now. We walked slowly past a row of sleeping faces, past a cleaner who nodded that nod people trade only at 3:15 a.m., out into the blank wind that smelled like rain trying to make up its mind.

Part II — My Table, His Story

My apartment is small, honest, and guarded by a porch light that always burns out two days earlier than I expect. I helped him up the steps, settled him on the couch, and brewed fresh coffee. He insisted on washing his mug first—a lifetime of pride in small chores. It grounded both of us.

He laid the envelope on the table between us like an unexploded shell. “You’re going to be angry,” he said.

“I’m already angry,” I said. “But that’s not the plan. The plan is facts.”

He ran a finger along the flap. “Your dad said signing those papers was a favor,” he said. “Said I’d still live in the house. Just… title in their name so they could ‘handle things.’”

“Did you see a lawyer?” I asked.

“‘Family doesn’t need lawyers,’” he said, quoting, tasting the words like they’d gone stale.

“Family protects you with paperwork,” I said. “Not against it.”

He held my gaze and then dropped his eyes to the mug. “Your grandmother used to do the forms,” he said. “I never was good with them. I can put a roof on a house. Couldn’t tell you how to keep one in a file.”

“We’ll start now,” I said. “We’ll do the forms that save you.”

He smiled without amusement. “I should have called you sooner.”

“Better late,” I said. “We’ll make it count.”

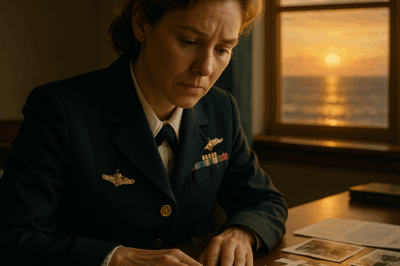

When he finally slept—breathing deep under my spare comforter on the couch because I couldn’t get him to take my bed—I opened my laptop and pulled the county recorder’s index. There it was: deed recorded five days earlier. Grantor: Walt Morton. Grantees: Richard and Elaine Morton. My parents. Not trust. Not life estate. Not anything that resembled decency.

I stared at the screen until the numbers blurred. My father was a retired accountant. He had taught me, against his own character, to balance a checkbook with a tenderness that surprised us both. He knew precisely what he had done.

By sunrise the rain tapped like a quiet person at a door. Grandpa stirred awake to the smell of toast. “You’re up early,” he said.

“I never really slept,” I admitted.

He rubbed his hands, the tremor a little gentler after heat and rest. “He called me stubborn last week,” he said. “Said I was set in my ways.”

“You built those ways,” I said. “There’s no shame in keeping them when they’re good.”

We drove to his house in the after-rain light. The shutters were freshly painted. The oak Grandma planted was a ground stump. There was a for sale sign leaning against the garage that made my stomach do the kind of move only rollercoasters should. I took photos of everything. The mailbox was empty, its flag bent down like a wrist someone had twisted. There were fresh tire tracks in the driveway, the kind you get when people carry the past out in boxes.

Mrs. Franklin from across the street came out in a bathrobe and shock. “Clare?” she said. “I thought you were in the city.”

“Came home,” I said. “How long since you saw him?”

“A month,” she said. “Your parents told us he moved to Florida with a nurse.”

“Florida,” Grandpa repeated, like someone trying out a word that doesn’t fit in his mouth.

I thanked her, and she told me she “didn’t see anything,” and we both understood she had seen everything important.

Back at my apartment, I photographed the papers in the envelope. The notary seal was wrong—wrong county, wrong name. The witness line was a single looping L. I sent the images to a friend in records. Her text came ten minutes later: signature matches an older document exactly; likely tracing. Not a good look for your folks.

“People hate when we make it real,” Grandpa said. He looked smaller and wider at once, like a house when you turn on the lights and see all its corners at the same time.

He dozed while I called Adult Protective Services and a prosecutor I trust in the county attorney’s office. I found the VA letter about the unclaimed widow’s pension and wanted to scream, not because of the money but because of the proof of neglect in black and white. I checked his meds—thirty-day pill organizer with too many empty days in the wrong weeks. I refilled what I could refill that day and made a list for the clinic.

My phone vibrated. Five missed calls from Dad. Then a text: Call us now. It’s not what you think.

I wrote back: We’ll talk to the DA. It’s exactly what I think.

Grandpa woke to chicken noodle soup that tasted like Grandma’s handwriting. “You’re her shadow,” he said. “She’d be proud you learned to make it with too much pepper like I like.”

“Too much pepper is a family trait,” I said.

He smiled and then looked into his bowl the way you look into a well and measure the depth by echo. “You think they’ll apologize?” he asked.

“Not soon,” I said. “But eventually they’ll have to face what they did. That’s not up to us.”

“Justice first,” he said. “Then pie.”

“Always.”

Part III — The Kitchen With Granite

I invited my parents to my apartment for dinner, not because I wanted to feed them but because my table is where my rules apply.

Mom arrived first, pearls, perfume, posture. Dad came in with a blazer and a jaw I’ve seen before, the one that says a man is about to pretend nothing that matters is happening.

“Where’s the old man?” he asked, looking around as if Grandpa were a misplaced umbrella.

“In the bedroom,” I said. “He’ll join us when he’s ready.”

They sat. I put tea on the table because nobody can claim someone is hostile when there’s tea. There’s a Midwest to me even when my badge is in the drawer.

“Clare,” Mom said, “this has all gotten out of hand. You don’t understand the pressure we’re under. Medical bills. Taxes. We had to refinance. It’s complicated.”

“Forgery isn’t complicated,” I said.

Dad’s eyes flashed. “You watch too much TV, Officer.”

“I watch too many seniors lose homes to people they trusted,” I said. “That’s what I watch.”

He leaned forward. “Don’t lecture me about family. You left.”

“You left him at an airport,” I said. “At night. After you took his title.”

Grandpa came out then, wearing his Sunday shirt. His voice trembled from use, not fear. “Then what should she lecture you about, Richard—money or conscience?”

Mom folded her arms around herself in a way that made her look smaller than she ever allows. “We’ve been taking care of you,” she said tightly. “Paying bills, sorting your meds, cleaning the house. You’d be in a nursing home without us.”

“This isn’t taking care of me,” he said. “This is taking from me.”

I slid my phone onto the table, the red recording light steady. “Say that again,” I told my father. “For the record.”

He glared at the dot. “You can’t threaten me.”

“You’re confusing my profession with my patience,” I said. “They’re not the same.”

He tried a different tactic. “We were drowning,” he said. “We thought he wouldn’t last another year.”

The room stopped breathing. He realized what he’d said exactly when I ended the recording.

“Thank you,” I said. “That’s what we needed.”

“You can’t—” he started.

“I did,” I said. “And so did you.”

They left with a smell of guilt I couldn’t get out of my curtains for days. Grandpa sagged back in his chair, a man who had a little less weight to carry because the burden finally had a name. “I didn’t want it to be this,” he said.

“I know,” I said. “But silence is a ceiling. We’ll move to bigger rooms.”

Part IV — Case Number, Parade Route

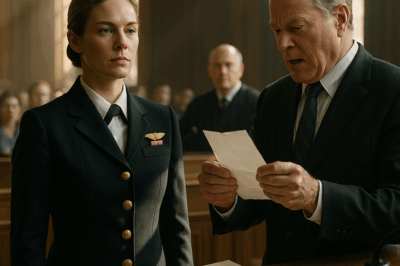

APS opened the case. Marjorie Weller—cat-eye glasses, cardigan that had fought winters—told me most families settle privately. “I’m not interested in quiet,” I said. “I’m interested in clean.”

The county attorney received the file with the kind of blank expression that means something is going to happen and it’s not a maybe. An old Marine turned lawyer—the kind who still starches truths—filed a notice of dispute at the recorder’s office and taught me the phrase undue influence in a way that felt like a lever.

“Win?” I asked.

“You already did,” he said. “They’ll fold. The question is whether you want your win whispered or announced.”

Honesty without humiliation. Grandma’s phrase. I chose daylight.

Colonel James Miller called from the veterans council and asked if Grandpa would consider being grand marshal for Memorial Day. “It’s a parade,” he said. “Not a deposition. But there will be microphones.”

“I haven’t worn the uniform in years,” Grandpa said.

“It still fits,” I said.

He smiled at himself in the mirror in a way that made the house stand up a little straighter. “Truth walks slow,” he said. “But it deserves a band.”

Memorial Day came with flag shadows on Main Street and kids with pinwheels and a brass band trying on several keys before settling. Mom and Dad stood near the reviewing stand as if they had been cast in a pageant against their will. Grandpa rode in a cherry red Mustang with Colonel Miller and looked like a statue that had decided it was bored and wanted to breathe.

He spoke into the mic with the control of a man who once held very different tools steady under worse skies. He didn’t name them. He named what they had done. He named what we had done. He named what he had survived. He said the thing that matters most.

“Sometimes the enemy isn’t overseas,” he said. “Sometimes it’s at your dinner table. That’s not treason; that’s a map.”

He pulled the envelope from his pocket. “Evidence belongs in daylight,” he said, and handed it to the district attorney standing under the banner with a face that gave nothing away and promised everything to the process.

My father shouted defamation because his vocabulary failed him exactly when he needed it. My mother cried without a handkerchief and looked around for someone to hand her something. The crowd didn’t heckle. They watched. Which is worse, if you’re guilty.

Grandpa finished with a sentence he stole from Grandma and now owns. “The truth might walk slow,” he said, “but it never limps.”

The band played the anthem. People stood. My father stayed seated, a small man in a chair too big for him. The DA’s office filed charges two days later: forgery, exploitation, financial abuse. They froze the accounts. Dad called me outside the precinct in an SUV that smelled like a salesman’s idea of success. Get in, he said. I didn’t. He said I’d ruined them. I told him he’d done it to himself and asked him to deliver a message: tell him I’m sorry. I hung up.

Mom came alone with stew. She apologized the only way she knew how—like a woman who still loves her first mirror more than her last. “It wasn’t supposed to go this far,” she said. “Fear makes fools of us.”

“Love makes them brave,” Grandpa said. “Choose.”

The DA offered a plea: restitution, probation, community service at the VA clinic. Grandpa surprised me by saying yes. “If they’re going to learn anything,” he said, “let them learn how to serve the kind of people they forgot I was.”

Part V — The Porch Light

Time thickened into the sort of days that make small towns feel like they might be survivable: VA clinic shifts, casseroles with names on masking tape, the sound of hammers fixing porch rails that should have been fixed when asked the first time. My parents completed their hours in Raleigh, carrying paperwork they would’ve once handed off, learning to say thank you without the comma of entitlement. The deed returned to Grandpa’s name. The bank apologized, which is the corporate version of bathing with cold water. The house began to smell like stew and lemon polish and the freshly legal.

Neighbors stopped by and said that what we had done had made their aunts call their lawyers. Veterans shook Grandpa’s hand and thanked him for a different kind of service. A young medic named Louise said her mother had filed a report after watching the parade because she recognized the glance he had used when he told the truth—a mixture of shame and relief. “Tell your mother she’s not alone,” Grandpa said, and meant it.

We hosted a barbecue in late summer. The Lawsons brought peaches. Pastor Don brought cobbler. The precinct ate too much. My parents came and kept their voices low and their hands busy. When Grandpa tapped his glass and said a few words, he didn’t pretend forgiveness is easy. He told the truth until it didn’t need adjectives.

“To family,” he said, “the ones who break you, the ones who mend you, and the ones who remind you who you are.”

We raised our glasses to that. Even my father.

At night, under the porch light, Grandpa admitted something I already knew. “If you hadn’t come,” he said, “I’d still be sitting at that gate.”

“I didn’t rescue you,” I said. “I remembered you.”

“Same thing,” he said, and I didn’t argue.

Fall came early that year. The leaves went rust, and the flag’s shadow stretched longer across the porch at dusk. My parents still came on Thursdays to help prepare meals at the clinic. They kept the plea deal. The plant Mom brought, a peace lily, bloomed again after I cut it back like the care card told me to. “Funny,” Grandpa said. “Your grandmother loved those. Said you have to prune the proud things to get them to behave.”

“Sounds like us,” I said.

He laughed, the sound I first heard at a gate under cruel lights. It had warmed.

When people ask what justice looked like in our case, I tell them about the envelope under the parade banner and the Monday morning summonses. I tell them about APS and affidavits and the way county clerks can look like saviors when they hand you a stack of notarized copies. But mostly I tell them about the porch light we leave on now, not as an apology, not as a warning, but as a signal.

Somewhere, another person is still sitting at a gate, shivering, empty envelope in hand, waiting for someone to come back. If you can be that someone, go. If you can’t, light your porch anyway.

The truth walks slow. It never limps. And under a light someone else forgot to switch on, honor knows the way.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I Thought It Was Just a Family Party, Until My SEAL Said, “This Isn’t a Birthday… It’s a Setup.”

It was supposed to be just a family party — laughter, candles, and a few harmless speeches. But halfway through…

CH2. I Thought My Father Died in 1991 — Until I Saw His Signature in the Navy Record…

They told me my father died in 1991 — a Navy officer lost in a mission no one would talk…

CH2. At My Commissioning, Stepfather Pulled a Gun—Bleeding, The General Beside Me Exploded in Fury.

At My Commissioning, Stepfather Pulled a Gun—Bleeding, The General Beside Me Exploded in Fury. Part I — The Shot…

CH2. At the Hearing, He Said I Didn’t Belong — Then the Judge Read: “Admiral Morgan.”

He called me a disgrace — right there in front of the judge. My father tore the envelope open, ready…

CH2. My Father, An Admiral, Secretly Gave My Promotion To His New Wife’s Daughter — BUT HONOR NEVER LIES

He took my promotion and handed it to his new wife’s daughter — the one who’d never worn mud, sweat,…

CH2. My Father Mocked Me in Front of 500 Guests — Until the Bride Said: “Admiral… Is That You?”

At my brother’s lavish wedding, my father raised his glass and humiliated me in front of 500 guests, calling me…

End of content

No more pages to load