My Nephew Wanted To Turn My Lakefront Cottage Into His Airbnb, So I Prepared A “Surprise.”

Part I — Keys, Water, and the First Phone Call

I signed for the cottage in a downtown Sidney office while October rain stitched gray threads across the window. The agent slid a thin folder toward me and offered the sentence people save for late-life beginnings. “Congratulations, Mr. Cartwright. It’s all yours.”

Mine. The word felt both too small and exactly right.

Forty minutes later I eased off the highway into a tunnel of arbutus and fir, the road shouldering down to Saanich Inlet. The cottage sat fifty feet from the tide line, cedar weathered to the soft brown of an old violin, windows squared toward the water like open hands. A great blue heron worked the shallows with priestly concentration. Across the inlet a ferry stitched white through gray.

I set the only chair where morning light would find it, shelved the books Margaret loved next to the pharmacy journals I had never had time to read, mounted my fishing rod over the door, hung my hammer on the pegboard. The first dawn, coffee in both hands, I watched the sun push a coin of light across the inlet and felt something unknot in my chest that I hadn’t known was tied.

In the evenings I phoned my sister. “I’m here,” I told Carol. “At last.”

“You earned it,” she said. “After everything with Margaret, after all those years behind that counter, you deserve quiet.” Then, in a tone I recognized from childhood, when she’d practice bad news like a foreign language, “Marcus is very interested in real estate these days.”

I said he was welcome to visit—call first. The arbutus kept peeling. The seals kept surfacing. A week later my phone lit up: MARCUS.

“Uncle Thomas!” Salesman bright. “Mom says you found waterfront. I ran the numbers. You’re sitting on a gold mine.”

He spoke without breath: Airbnb, peak season rates, ROI. “We’ll turn your place into a short-term rental,” he said. “You can keep the back bedroom when there aren’t guests. Best of both worlds.”

“My cottage isn’t a portfolio item,” I said. “It’s a home.”

“Don’t decide now. Sleep on it.” His tone cooled a degree. “You’re alone out there. What if you need cash for medical? At least consider it.”

“I have. No.”

We hung up politely—there’s a special Canadian register for that—and the heron stabbed the water and came up shining.

Three days later Carol called, careful as a surgeon. “He says you dismissed him. He’s enthusiastic, that’s all.”

“He wants me in the back room of my own cottage,” I said. “Enthusiasm isn’t the right word.”

“You sound… harder,” she said.

“I sound like a man who worked thirty-seven years for a thing and intends to keep it.”

After I hung up I took out a legal pad—old pharmacy habit—and wrote what had been said, when, and by whom. You don’t document for drama. You document for clarity.

Two weeks of tides and kind chores later, a sedan crunched the gravel unannounced. Marcus and his partner, Vanessa, stepped out the way people step into open houses—with eyes that tally.

“It’s smaller than the listing made it seem,” she said.

“What listing?” I asked.

“Old photos,” she said lightly. “We’re just being thorough.”

They sat at my kitchen table without being asked, and Marcus opened a spreadsheet as if he were a magician about to produce doves.

“Gross sixty thousand,” he said. “Expenses twenty to twenty-five. Net thirty-five to forty. Fifty/fifty split. That’s twenty thousand a year in passive income for you.”

“I want active quiet,” I said. “Not passive chaos.”

Vanessa leaned forward, voice dialed to Gentle Concern. “May I be frank? You’re sixty-four, Thomas. What’s your five-year plan? We’re offering a solution.”

“My plan,” I said, “is coffee at dawn and the heron at seven.”

On their way out Marcus turned. “You might not get terms this favorable again.”

After their taillights went, I called Carol. “Did you tell him I’d be ‘difficult’?”

“I told him you were attached,” she said. “He’s worried. We both are.”

“I’m solitary,” I said. “Not unsafe.” Then I wrote that down, too.

Part II — Posters, A Website, and the First Edge of Fraud

Two weeks later I stopped for beans at the café in town and found my view in the window—my deck, my arbutus—in glossy color beneath the words Stunning Waterfront Cottage—Book Your Dream Getaway. A QR code blinked like a dare.

“Who put that up?” I asked the barista.

“Guy paid cash,” he said. “Said he’s managing bookings.”

Back in the truck I visited the website. A name I hadn’t chosen glowed at the top: Saanich Inlet Retreat. There were interior shots—a photo through my window of my chair—and a calendar with three blocks of red: reserved. Rates: $300 per night. Minimum two nights. A Gmail at the bottom: saanichinlet.rentals.

I called the agent who sold me the place. “I need a property lawyer,” I said. “One with sharp edges.”

Richard Morrison’s office smelled like paper and rain. I slid my laptop across the desk. He looked. He nodded. “This is fraud,” he said. “Civil: cease and desist, injunction, damages. Criminal: RCMP—fraud over $5,000 is indictable.”

“Send both,” I said. “All of it. Also I’m installing cameras.”

By afternoon I had two motion-activated eyes on the driveway and the deck and one watching the tree line. The next evening a courier delivered Morrison’s letter to the Vancouver address Marcus used on his business cards: take down the site, refund all payments within twenty-four hours, no further contact except through counsel, or we proceed civilly and criminally.

At seven p.m. my phone rang. “You had your lawyer threaten me,” Marcus said. “Over a misunderstanding.”

“You listed my home for rent,” I said. “You took money. There’s no misunderstanding.”

“I advanced our plan,” he said. “I thought you’d come around when you saw I was serious.”

“I was serious when I said no.”

“You wouldn’t charge your own nephew,” he said, testing the word own like a key. “Be reasonable.”

“Be legal,” I said, and hung up.

At 9:31 the deck camera caught Marcus pacing the boards I’d sanded with my own hands, trying the knob, peering like a burglar who thinks family makes him a guest. He left after a long minute with his hands in his pockets and his jaw set.

Three days later a constable in a bun and a weatherproof smile knocked softly on my door. “Constable Shu,” she said. “I hear we have a problem.”

I showed her the website, the poster I’d pried out of the café window, the cease and desist, the grainy night visit, the pad with dates and quotes. “I can’t prove he took payments,” I said, “but the calendar is blocked.”

“If he shows with ‘guests,’” she said, “call me. Don’t open the door.”

He showed at dusk the next day, right on the time block I’d screenshotted—his car first, a rental Kia behind it. He knocked like he owned me. “Uncle Thomas,” he called, cheerful and strained. “My guests are here.”

The couple beside him looked like the kind of people who get up early to beat ferry traffic and buy fresh bread. Confusion sagged their shoulders. I filmed from the dark of my hallway and dialed Constable Shu.

She arrived in twenty minutes, brisk on the gravel, voice clipped and kind. She took the Kia couple aside, and they left in a spray of humiliation and kindness. She handed Marcus papers—the injunction—then said something my porch microphone caught perfectly: “Mr. Cartwright has asked for a criminal investigation. You’re to cease operations, refund immediately, and have no contact except through your lawyer.”

He reddened the way you do when story and law disagree.

That night, quiet reclaimed its reins. Then the phone rang: Carol, fury threaded through grief. “You called the police on my son?”

“Your son tried to run a rental through my home,” I said. “He took deposits. That’s not a misunderstanding. It’s criminal.”

“You could have handled it as family,” she said.

“He could have respected the word no,” I said. “He did not.”

“Margaret would be ashamed,” she said, and the line went dead under the weight of a sentence designed to bruise.

I went out to the deck because cold tells the truth. The heron wasn’t hunting; the tide was too high. Across the inlet, a ferry cut a slow white seam. I stood there until the wood under my feet borrowed my heat and gave it back.

Part III — Crowns, Costs, and an Open Door

Legal processes are both glacial and immediate. Morrison filed for an injunction; the court granted it. Damages in civil court: eleven thousand, plus costs. Crown Counsel reviewed the file for criminal fraud. Marcus called once through his lawyer to ask whether I’d withdraw the complaint “in exchange for reconciliation.” I answered through mine: “No.”

In December the RCMP charged him formally: fraud over five thousand. He took a plea—a conditional discharge, two years’ probation, twenty-five thousand in fines and restitution counting the civil judgment. Morrison explained the math: “He avoids jail if he behaves. The record can be cleared later if he finishes probation. But it’s still a record now.”

The day Morrison called with the news, my phone buzzed with a number I didn’t know. “Vanessa,” the text said. “You ruined his life.”

I deleted it without the dignity of a sigh.

That night Margaret’s photo on the mantle found me. I poured two fingers of scotch. “Would you have done it differently?” I asked the woodstove.

She’d been the gentler of us, but not soft. She’d once told her brother no when he asked for a loan we didn’t have. She sent a Christmas card anyway. “Be kind,” she’d say. “And be clear.” The trick was to keep both.

I wrote an email to my sister. I love you. I’m sorry for what this has cost you. The door is open when you want to talk. I will not apologize for protecting my home.

In January a familiar car idled in the snow on my camera feed. I opened the door before Carol could knock. She looked smaller, as if words had been heavy. “He took the deal,” she said. “He and Vanessa are… not together.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, because sorrow can sit beside relief at the same table.

“You could have stopped it,” she said.

“He could have,” I said.

We had tea with our fingers around the heat the way people hold on to new rules. She looked around the room as if she were seeing it for the first time—Margaret’s photo with three daisies we used to pretend were for her allergies, the books arranged by a logic I didn’t have to explain to anyone, the way the inlet framed itself.

“It’s beautiful,” she said.

“It is,” I said. “It’s also quiet.”

“I enabled him,” she said finally. “All of us did. I thought I was supporting his ambition. I was teaching him he could take.”

We watched the heron—my heron—land and stand like a guardian of nothing. “Can I come again?” she asked at the door. “Not right away. But again.”

“Call first,” I said. “I like my solitude.”

She almost smiled. “That sounds like you.”

Part IV — The Surprise

People ask me later what the “surprise” was—the thing I’d prepared for weeks after the posters and the website, the part that meant when Marcus arrived with paying “guests,” everything fell in like a tide.

It wasn’t a trap in the cinematic sense. It was a collection of quiet edges:

— The cameras, installed before he thought to show his first renters where the towels were. One pointed at the drive, one at the deck, one at the long dark under the arbutus. Motion activated. Cloud-stored. Time-stamped.

— The paper trail, written in the block letters that had recorded dosages for thirty-seven years. Dates, words, offers declined, calls logged, a copy of the cease and desist with the courier’s signature and the time stamp circled.

— The injunction itself, filed before his first check-in. Not a threat. A legally binding surprise.

— And the phone number on a card by the door: Constable Shu’s direct line, with her calm voice attached to it, the kind that says this won’t be a fight, this will be a procedure.

He thought he’d walk up my deck with people he had taken money from and watch me cave because family. He found the criminal code instead, already waiting with the ink dry and the camera blinking red.

The rest is less story and more living. Winter thinned. The arbutus bled its bark and looked new. Orcas ghosted the inlet once, three fins cutting the gray like punctuation in a sentence written in black water. I replaced a dock plank I decided I disliked on principle. I tried a different brand of coffee and didn’t like it and went back to the one that tastes like mornings in a house that remembers you.

The heron taught me patience by example. The ferry taught me schedule without obedience. The inlet taught me how to own something without owning any part of the light that falls on it.

Sometimes I still hear Carol’s voice on the phone the night she tried to cut me off with the memory of my wife. It stings less because I refuse to let it take anything from Margaret as an instrument. Grief doesn’t like to be wielded. It likes to be held.

Once, late in spring, I found a new poster in town—Bold Investors Network: How to Build an STR Portfolio—with a line of sponsors whose names I didn’t recognize and one I did. I took a photo and sent it to Morrison without comment. “Habits take time to break,” he wrote back. “But consequences help.”

If you’d asked me at the start whether I wanted any of this—the injunctions, the calm constable, the word fraud printed near my family—I would have said no. What I wanted was perfectly ordinary: a chair in morning light; a stove that behaves in snow; a kitchen shelf that holds both Margaret’s novels and my stubbornness. I didn’t move to the inlet to learn the law. I moved to learn the loons.

But boundaries are the quiet kind of love you give to yourself when no one else will. The surprise wasn’t a trap. It was a refusal to be taken.

These days I sweep the deck before the first ferry horns, make coffee, listen for the heron’s wings, and check the cameras only when a crow’s curiosity sets them off. The website is down. The posters composted the way paper should. The only calendar that matters is the one the tide keeps.

If you stand on my deck at dawn, you can hear the inlet breathe. If you turn the knob on my door, it will open—to the right key, not a master one. And if my nephew ever walks this gravel again, I’ll hear his shoes, pour two cups of coffee, and meet him at the top of the steps with two sentences that are not mutually exclusive: I love you. No.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. Navy SEAL Asked Her Rank As A Joke — Then Captain Made The Entire Base Go Silent

Navy SEAL Asked Her Rank As A Joke — Then Captain Made The Entire Base Go Silent Part I…

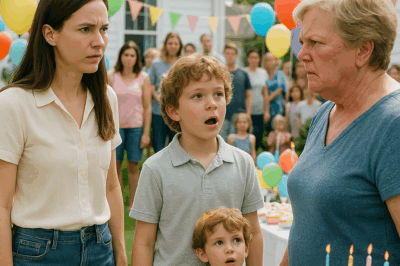

CH2. MIL Called My Twins ‘FAKE GRANDKIDS’ at Their Party—Then My 8yo Exposed Her 40-Year Secret

MIL Called My Twins “FAKE GRANDKIDS” at Their Party—Then My 8yo Exposed Her 40-Year Secret Part I — Paper…

CH2. My Sister Slapped Me At Family Dinner And Mom And Dad Clapped Behind—So I Gave Her Five Minutes To…

My Sister Slapped Me At Family Dinner And Mom And Dad Clapped Behind—So I Gave Her Five Minutes To… …

CH2. My Brother Laughed at My Father’s Funeral—Then a Nurse Handed Me an Envelope That Changed Everything

My Brother Laughed at My Father’s Funeral—Then a Nurse Handed Me an Envelope That Changed Everything Part I At…

CH2. HOA Karen Calls 911 After Her “Master Key” Can’t Open My Lake Cabin — Unaware My Son Is The Sheriff!

HOA Karen Calls 911 After Her “Master Key” Can’t Open My Lake Cabin — Unaware My Son Is The Sheriff!…

CH2. You Earn $3K, Why Is Your Child Hungry? DAD Asked “My Husband Proudly Said, I gave Her Salary To..

When Dad came to take my son for the weekend, he opened the fridge — it was completely empty. Shocked,…

End of content

No more pages to load