My Mother-In-Law Burned My Wedding Dress Right Before the Ceremony to Stop Me from Marrying Her Son

Part I — Smoke

I didn’t smell the fire at first.

What I smelled was gardenia—the perfume Evelyn always wore like a signature she wanted to force on the room. It got there before she did, the way expensive things tend to. Then came the click of her heels on the marble corridor and the hush that fell through the bridal suite because everyone felt it at once: a front rolling in from the ocean, bringing weather.

She stood in the doorway of the dressing room in a dove-gray column of a gown that shimmered when she moved. Pearls at her throat. A smile that never reached her eyes. She held a long matchbook between two fingers as if it were jewelry. It took one beat for me to understand. Two for my body to go still. Three to realize I had already dreamed this and survived it.

“You’ll never be part of this family, Sarah.” Her voice sounded almost wistful. “You think that cheap little bronze star makes you worthy of my son? You’re a disgrace.”

I have been shot at in a ravine while applying a tourniquet with my teeth. I have crawled beneath a burning vehicle to drag out another medic who was calling for his mother. I have set bones on the side of a road with one hand while holding back a line of soldiers with the other. I know how to freeze myself until the air around me crackles with it.

So I stood there. Calm. Listening.

It is a small thing—a whoosh—and then a roar. Silk is a lesson in combustion. Satin, a hymn to ruin. The flame caught at the hem of the dress first, yellow tongues tasting the edge of the lace I had spent three evenings hand-stitching onto the underskirt while Lucas slept on the couch with a book open on his chest.

I did not move.

Behind me, my maid of honor—Marley, who knows where all my old ghosts lie—made a sound I will carry with me always, half warning, half grief. “Sarah—”

“Don’t,” I said quietly. “Let her finish what she started.”

Evelyn laughed, a little burst of sound like glass breaking in a sink. Smoke curled for the ceiling, delicate as ribbon. The bouquet on the vanity browned and then blackened. The smoke alarm woke up, offended, and began to scream.

“Maybe now,” she said, “you’ll understand your place. You’ll walk away before you humiliate yourself further.”

“You have no idea what you just did,” I whispered.

Her smile faltered.

It wasn’t the dress. The dress was a symbol, yes, and a pretty one—fit like a secret, train like a letter dragged behind a car leaving town—but it was not the thing I needed to keep. What she burned wasn’t silk. It was the last thread holding back everything inside me I’d carefully folded and put away for this day.

I picked up my phone with steady hands and called the fire marshal.

“There’s been an intentional fire at the Carlton estate,” I said, loud enough for her to hear. “The owner of the property is responsible.”

The color fell out of her face so fast it made me think of photographs left in a hot car.

“You wouldn’t dare.”

I tilted my head. “Try me.”

Within half an hour, the foyer of the house she loved more than any person was full of firefighters and the hum of official voices. The dress was gone by then—lace confetti in a circle of ash where it had died—and a second, smaller fire she hadn’t meant to start had climbed a curtain near an overloaded outlet. It had scorched a gilt frame and licked at the antique damask drapes Evelyn liked to tell people were “Louis-something” in exactly the way you say a word for its taste, not its meaning.

Lucas arrived in a shock of blue suit and panic. He came toward the smell of burned fabric like a man moving against wind.

“Mom,” he said, hollower than I’d ever heard him. “What happened?”

“She set her own dress on fire,” Evelyn told him, breathless, wild. “She did it to make me look—” She stopped because she could hear herself and because the fire chief, who had already pulled security footage, was coming down the hall.

“We’ll need your statement,” he said. He looked at me and then at the screen in his hand and then at her.

The truth has a way of dropping into a room like a plumb line. You can ignore it. You can shout over it. But it hangs there, unforgiving, reminding you what straight is.

The video showed her clearly: the way she looked around and closed the door with care, the little flourish with the bottle of lighter fluid, the childlike delight as the flame became performance.

“Mom,” Lucas said again, but this time it was a fact, not a request.

She reached for him and he stepped back.

“You just ruined the one thing that mattered most to me,” he said. He didn’t shout. He didn’t weep. He sounded like a man telling a surgeon to stop cutting.

That was the last time I heard him call her Mom.

Part II — The Letter and the Fuse

I wish I could tell you I felt triumphant when the footage played. That the satisfaction came like a warm flood. It didn’t. What I felt was the click of a switch labeled Now.

A week earlier, an envelope had arrived at our apartment without a return address. Inside were photos of Mark, my first fiancé, who died under a sky that smelled like diesel and fever. Someone had used his memory as a weapon against me, printed grief on glossy paper, and promised to send it to my future if I didn’t step aside.

I didn’t know who had sent it until the fire, until the commotion in the drawing room knocked Evelyn’s designer purse off a side table and the same stationery fluttered out—cream with a hairline gold border, my name in a hand that tried to look neutral and failed.

Here is how you dismantle a fortress built on image: you don’t kick the door; you take out the floodlights.

I paid a visit to a friend at a local paper and then to a woman I’d met at a VA panel who ran a watchdog account for nonprofit spending. I didn’t rant. I didn’t accuse. I handed them a thumb drive with the video, copies of the blackmail letter and the envelope it came in, a timeline of recent foundation disbursements that did not match public filings, and a list of vendors who had never been paid. I hired a forensic accountant for one week and treated the results like flares.

When the story broke—SOCIALITE TORCHES BRIDE’S GOWN; FOUNDATION FUNDS IN QUESTION—it took six hours for donors to put statements on their websites and four days for the board of Evelyn’s beloved charity to ask for her resignation. She resigned with a paragraph about “focusing on family” that reporters quoted beside a photo of the burned lace. Someone captured her leaving the house under an umbrella, and the internet did what the internet does when hypocrisy finally has a face.

Lucas and I got married two weeks later in a chapel that could have been a broom closet for all I cared. I wore a knee-length white dress I bought for $110 at a vintage store and a pair of boots that had seen Afghanistan. Marley braided a ribbon into my hair. The chaplain from the clinic where I volunteer read a poem about steadiness. We promised to do what we had already been doing for years: choose each other on purpose when it was easy and twice when it was not. We signed our names, hands shaking but not from fear.

There is a peace particular to rooms without flowers. I have come to love it.

Part III — The Knock

Two months after the fire, someone knocked on our door past midnight. The knock wavered—not timid, exactly, but unpracticed. I opened it to find a woman who used to throw parties standing in the rain like a stain trying to wash itself out.

Evelyn held a photograph of Lucas at five. He was in overalls, hair like a wheat field, and looking at the camera as if it were a question he meant to answer. The rain had made her mascara travel. She looked small the way expensive things look when you put them under real light.

“Please,” she said. “I’ve lost everything. My reputation. The house. My son. Tell him I’m sorry. Tell him I didn’t mean—” She stopped because even she could hear the word mean asking too much of her.

“You did mean it,” I said. Not cruel; just precise. “You meant it every time you said he was too good for me. Every time you told him strength was the same thing as control. Every time you used love like a currency and then were surprised when it didn’t spend.”

She sank to her knees on our porch like a woman at a river that refuses to part.

“I was trying to protect him,” she whispered. “You’ve seen… you know what war does to—” She gestured at me as if soldier were a slur.

“I do,” I said. “It made me better at telling the truth. It taught me where to stand.”

We are not required to be brave and kind at the same time. Sometimes the kindest thing is a locked door. Sometimes bravery looks like not opening it.

“I’ll tell him you were here,” I said. “I’ll tell him you’re sorry. But forgiveness is not a coupon. You don’t clip it and hand it over at the register.”

I closed the door as gently as I could. I stood with my forehead against the wood until I could breathe evenly again. In the morning, I told Lucas. He nodded slowly, pain and relief passing across his face like weather.

“She’s never said sorry,” he said.

“She did,” I answered. “When it was the only thing left to spend.”

Part IV — The Work

If stories ended where people expect them to, I’d tell you Evelyn disappeared into a smaller life and we lived in the larger one she tried to burn down. But people don’t change because they’re caught. They change because staying the same becomes a worse pain.

Three months after the rain, the volunteer coordinator at the VA hospital told me someone had joined our Tuesday afternoon shift in the physical therapy wing. “New intake,” she said. “Late fifties. Quiet. Good with towels. Not great with small talk yet.” She showed me the roster.

It was not lost on me that the first place Evelyn tried to be useful in years was a room where nobody cared how much you’d given to galas if you knew how to hold a leg steady while a man learned to walk again.

We did not pretend to be friends. We learned each other’s names slowly the way you learn the weight of a pitcher before you pour. She folded blankets like prayer. She watched the way I placed my hands along the length of a scar, thumb and index finger making a Z of pressure to teach tissue to move again. She stopped wincing when someone cried. She stopped flinching when I walked into the room.

If you are looking for glory in redemption, you will be disappointed. It looks like the ninth time you show up when nobody asked you to and there’s an empty cart that needs stocking and you do it without sighing.

One day, between sessions, the volunteer coordinator handed me an envelope with no name on it. Inside was a letter in a hand I had only seen on place cards.

Sarah,

I used to think that if I’d had your courage I would have been kinder. I can see now I had plenty of chances to try. I don’t expect you to trust me. I do hope you will let me keep showing up where it matters and learn from people who have been brave in ways I cannot imagine.

I am proud my son married someone who knows the difference between spectacle and service.

—E

I didn’t show it to Lucas that day. Not because I wanted to keep it, but because I wanted to sit with the odd place inside me that letter reached, the place where grace lives like a small stubborn animal, mistrustful and warm.

I wrote back one line and left it in the volunteer bin.

Show up again next Tuesday.

She did.

Part V — The Dress

We had a wedding album, even though there hadn’t been a dress to photograph. Marley put it together, all cream paper and handwriting that belongs in books of poems. The first picture is Lucas’s hand holding mine over a chipped wooden pew. The second is my boots by the chapel door beside a pair of polished oxfords. The third is a photo Marley took out the car window of a sky the color of forgiveness.

On our first anniversary, Lucas came home with a box that looked like it belonged in a movie where people propose under string lights. Inside was a dress. Knee-length, honest. The hem stitched by a seamstress who left her name inside like a blessing. He’d asked her to sew a small piece of my burned lace into the lining where no one would see it and I would always feel it against me when I moved.

“Not a replacement,” he said. “A reminder.”

That night we ate takeout on the living room floor. I set one white lily in a glass of water between us the way you put a candle in a window when someone is trying to come home.

I don’t think about the fire every day. Trouble doesn’t own me. But when the movie of my life gets still, sometimes I see smoke curling toward a ceiling, and I see my hand holding a phone like a weapon built for truth, and I see a woman built of performance watching a screen tell her who she is.

And I think: we are made by the things that try to burn us down. Not ruined—made. The trick is to decide what to build with what’s left.

Part VI — Ashes and After

If you need the clean ending, it’s this: We are married and steady. The estate was renovated and sold to settle the foundation’s debts after the board forced Evelyn out; she lives in an apartment a bus ride from the hospital and makes a soup I would not eat again. She calls Lucas once a month on Sundays; he answers every other. It’s a move toward the light that costs him less each time.

Some days I catch her watching me tape a patient’s ankle and I can feel her working at a sentence tested on her tongue: “I was wrong.” It matters less now if she ever says it. The saying is in the showing.

There is a framed photo on our hallway table of five shadows on a bright day—me and three men moving forward, one leaning on the other two, Evelyn a step behind with a towel over her arm. If you didn’t know, you couldn’t tell who had once held a match.

On our second anniversary, Marley asked if I wanted to try on a dress for fun. “I have a friend with a sample rack,” she said. “We can play.”

We went and laughed and let silk whisper along skin, and I did not feel haunted. A saleswoman asked where my mother was, and I said, “At work.” It was a truth I liked.

When people ask about my dress—the one that burned—I don’t tell them about flames. I tell them about a chapel with no flowers and a room that knew our names and the way a man took my hand like he meant to keep it. I tell them about ash that nourishes soil. I tell them about lilies that grow in water and refuse to drown.

And when I think of Evelyn, I think of bandage tape on her white blouse, of a woman learning to listen to someone else’s pain and say the only useful sentence: “Tell me where it hurts.”

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. Was On Bed Rest After Surgery When My Sister Texted, ‘You Can Watch My Kids For A Week, Right? I Just Booked A Trip To Paris!’ I Could Barely Walk, But She Didn’t Care. So I Decided To Teach Her A Lesson She’d Remember Forever. When She Came Home From France, She Walked Into A Scene She’ll Never Forget…

Was On Bed Rest After Surgery When My Sister Texted, “You Can Watch My Kids For A Week, Right? I…

CH2. ‘You need to move out’ my parents said on Christmas. “Really?” I replied, the next morning, I packed & left … Now they’re stuck in a lie…

“You need to move out,” my parents said on Christmas. “Really?” I replied. The next morning, I packed & left…

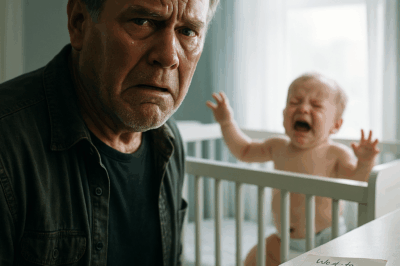

CH2. I used my spare key and found my grandson in his crib, screaming, unchanged for hours. A note said: “Went to Bahamas with girlfriends – back next week. Baby will be fine.” I called my daughter, furious. She laughed, “Dad, relax!” I contacted police and cps. When she returned, she found herself in a

I Used My Spare Key and Found My Grandson in His Crib, Screaming, Unchanged for Hours. A Note Said: “Went…

CH2. My Brother Mocked My Inheritance: I Got The Old House, He Got Dad’s Business — Until The Lawyer…

My Brother Mocked My Inheritance: I Got The Old House, He Got Dad’s Business — Until The Lawyer… Part I…

CH2. At The Family Dinner, I Told Mom I Was Excited for My Sister’s Wedding. She Said…

At The Family Dinner, I Told Mom I Was Excited for My Sister’s Wedding. She Said… Part I — The…

CH2. My Girlfriend Insisted I Apologize to Her Male Best Friend for Upsetting Him. I Complied. I Visited His Home and Said, in Front of His Wife: ‘I Deeply Regret Not Telling My Girlfriend About the Affair You Had Last Summer. I Shouldn’t Have Kept That Secret for You…’

My Girlfriend Insisted I Apologize to Her Male Best Friend for Upsetting Him. I Complied. I Visited His Home and…

End of content

No more pages to load