My Mom Said: “You Shouldn’t Exist,” Everyone Laughed — Except Me

Part I — The Edge of the Frame

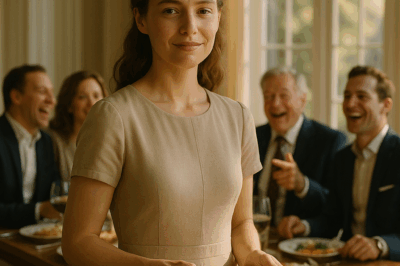

My mother said it as the chocolate cake was being sliced, her voice light as sugar, her words sharp as glass.

“I wish you had never been born.”

For a heartbeat I thought I’d misheard her. Then my father laughed—an easy, tipsy chuckle. Samantha, the eldest, threw her head back and clapped like it was a courtroom victory. Olivia choked on a giggle and reached for her phone to capture the moment she thought was funny.

I didn’t laugh. My fork stayed still. The chandelier turned red wine into rubies, candlelight made our silverware glow, and everything looked picture perfect if you didn’t listen too closely. I listened. I always had.

My name is Claire Mitchell, thirty-four, head nurse at a Dallas hospital. I spend nights coaxing pulses back from the brink, memorizing medication dosages and the way fear sounds when it tries to be brave. I live alone in a quiet townhouse, divorced and unashamed. People like to assign grades to women like me: A+ for independence or F for failing to follow the script. I don’t sit for their exams anymore.

We were three daughters, but at home it never felt like three. Samantha was the parade—debate captain, scholarships, shiny plaques—and my parents lined the streets every time she passed by. Olivia was the poem—oil paint under her nails, a gallery opening she might open, an artist’s melancholy my mother called “creative freedom.” And me? I was the corridor between the rooms. If something broke, I fixed it. If voices rose, I lowered mine and paid the bill.

I used to tell myself I wasn’t jealous, only peripheral. In every photograph I stood at the edge of the frame, half-turned or half-hidden. I laughed about it, once. Then the sound turned hollow.

That night the house in Plano looked exactly as it had for a decade of holidays—Samantha’s diploma framed above the mantle, Olivia’s canvases leaning like clever secrets against the wall. My mother wore an apron and the satisfaction of a woman who had set a table well. My father smelled like cologne and good cheer.

We gathered for Thanksgiving, but really we gathered for Samantha’s promotion to senior partner. I arrived early and did what I always do: whisked gravy, straightened napkins, carried plates. “Is Samantha on her way?” my father asked, patting my shoulder with the absent gratitude of a man who has mistaken furniture for family. “Probably,” I said, and he beamed.

When Olivia breezed in, she kissed everyone and looked at me with a smile that said she loved me, just not loudly. “You look tired. Did the hospital wring you dry again?”

“Yes,” I said, and smiled back. Her hands still smelled faintly of linseed oil. She lifted a phone to show our mother a photograph of her newest painting—smoke and color and the faint outline of a woman dissolving at the edges. Everyone gasped as if a miracle had occurred. Maybe one had. I’d brought a different miracle with me: that morning, after three minutes without a pulse, I’d pressed and breathed and pleaded a seventy-year-old heart back into rhythm. When his eyes opened, he said my name like he’d known it forever.

I tried to tell that story at the table, between a second pour of wine and one of my father’s old favorites about Samantha’s first debate trophy. “He came back,” I said softly. “After the third round of compressions. He looked at me like…” I searched for an exact word, the kind nurses don’t have time to find.

“That’s your job, isn’t it?” my mother said, smiling at Samantha. “Nurses save people.”

As if saving were a shrug. As if breathing were something you check off a list.

The conversation moved along without me. It always did. I smiled where appropriate, nodded when it helped, carried dishes when there was nothing else to do. Eventually dessert arrived—my grandmother’s cake, the one my mother only made “for important events.” The room warmed with cinnamon and the glow of being a family that believed itself good.

And then, like the punchline to a joke we’d rehearsed for thirty years, my mother began: “Do you all remember how we used to tease Claire? That time we told her she was adopted and she cried for hours?”

Laughter broke around me like surf. My father dabbed at his eyes. “She was so gullible.”

“You packed a backpack,” Olivia gasped, delighted by her own memory. “You were eight and tried to run away.”

My mother kept going, story after story, each laugh snagging on the old scar tissue in my chest. The lipstick drawn on my sleeping face. The mirror ghost. The neighbors who thought the house was on fire because my scream was that sharp. I remembered how she’d held me afterward and how she’d laughed with the others anyway. You’re too sensitive, Claire.

The room blurred at the edges. I listened to their laughter—the past layered over the present until time itself felt like mockery—and realized an old truth: they didn’t laugh with me; they laughed to me, at me, through me. I was entertainment. I was the subject, not the person.

“Come on, Claire,” my father said kindly. “You have to admit it was funny.”

“Funny for who?” I asked, and he looked confused, as if I’d forgotten my cue.

Olivia smirked. “You’re so serious all the time. It’s like no one lasts ten minutes in a conversation with you.”

Her words drifted down, light and cutting. Somewhere inside, a string that had been stretched across years finally snapped. The sound was small and absolute. When my mother said, I wish you had never been born. Maybe then this family would finally be at peace, she said it to the cake.

The fork in my hand touched porcelain with a clean, bright ring. I set it down, looked at each of them the way you look at a painting you’re memorizing before you leave a museum, and felt nothing but a stillness so complete it frightened me with its mercy.

“If that’s what you truly want,” I said, voice steady, “I’ll make it come true.”

No one laughed. My mother attempted a smile and failed. “Oh, Claire. I was only joking.”

They had said that about the orphanage. About the ghost. About the lipstick. A lifetime of punchlines.

I pushed back my chair, folded my napkin, and stood. The legs scraped the floor like a blade. I didn’t look at any of them as I walked out. The door clicked behind me with the finality of a held breath exhaled.

The Texas night had started to rain. I inhaled the cool and tasted metal. Somewhere inside that house they would have fallen into a silence they did not recognize, and for once it would not be mine to soothe.

On the drive home I did not turn on the radio. The tires sang a low, continuous note. By the time I reached my townhouse the decision had already happened, the way a heart decides to beat again. I opened my laptop and searched nurse leadership positions Seattle. The screen filled with possibilities. Each application I submitted sounded like scissors snipping a cord I hadn’t realized was strangling me. I changed my number. I muted every thread. I deleted the contacts that only dialed when they wanted something and the ones that never asked if I needed anything at all.

At two in the morning I walked the perimeter of my small living room and saw it as if for the first time—not as the place I came to collapse, but as a witness. I touched the window, saw my face reflected, and said the kind of promise a nurse trusts: From now on, no one gets to hurt you. Not even them.

Outside, the rain kept time with my breath. For the first time in years, tomorrow didn’t scare me.

Part II — Silence Has a Sound

The calls started three weeks later, first like a drizzle, then like weather. Mom. Samantha. Olivia. Dad. I watched the phone light, go dark, light again. I changed my ringtone to silence, then turned the phone off entirely during breaks because I was afraid of the sound of my mother’s voice. I could survive almost anything, but Claire, I’m sorry might kill me.

One afternoon I came home to a knock that sounded like a past trying to get in. I stood behind the door and listened as my mother sobbed on the other side, words tumbling over each other.

“I didn’t mean it. I was angry. Please come home. I can’t sleep, I can’t eat. I miss you, sweetheart.”

I pressed my palm to the wood. I pictured the flowered apron, the silver in her hair, the careful way she would have practiced those sentences. The muscle memory of daughterhood drew breath to open. The new muscle I had just learned how to flex held me in place.

She waited. She left. The silence she always assigned to me was now hers to carry.

That night, in my inbox, a Seattle hospital wrote: We’d like to interview you for the unit supervisor position. I read the email twice, then a third time, as if a promise could be made more true by repetition. Six weeks later my townhouse was scrubbed clean, the keys slid through a mail slot, and my life fit into two suitcases and a box of books I couldn’t imagine not touching again.

From the plane window Dallas sprawled in beads of light, the net I’d been caught in suddenly delicate enough to break. I didn’t cry. Relief can look like emptiness when you’ve never seen it up close.

Seattle met me with coffee breath and a sky that could not decide what it wanted. I found an apartment near Lake Union where mornings smelled like wet leaves and engines, and nights wore fog like linen. My first day at the new hospital I caught sight of my reflection in the entry glass—white coat, simple bun, tired eyes—and thought, she looks like a person.

No one here knew me as the middle Mitchell girl, the invisible engineer of peace. In staff meetings my name was called with respect instead of request. A new grad nurse cried in the supply room one evening and said, “Thank you for seeing me,” and I laughed softly because I had never been thanked for sight before.

Winter put its hand on the city. I learned how to move inside it. I let the rain touch me instead of outrunning it. I cooked soup for myself. I bought a lamp that gave off a good small light and left it on when I wasn’t home just to see warmth waiting.

In February, a former colleague called. “Claire, are you okay?” she asked, and then, before I could answer, “I saw your mom. She’s thinner. I heard your dad moved out. Your sisters… there’s fighting. Money. The Plano house. Thanksgiving was canceled.”

I thanked her, hung up, and stood at my window. The lake reflected a thousand jittery city lights. I pressed my fingertips to the glass and felt the cold through the pane. I didn’t feel vindication. I didn’t feel nothing. I felt recognition.

When the person who keeps the peace finally leaves, silence becomes the loudest thing. They were hearing it now, the sound I had known since childhood—the distance between mouths that speak and ears that refuse to.

A week later I walked into a café near the hospital to escape a night shift’s hangover. The only open seat sat by the window. “May I?” a man asked, nodding to the chair across from me. He had the look of someone who understood weather—quiet, polite, the outline of sorrow worn well.

We talked about nothing in a way that felt like something. The Mariners, the way Seattle drivers behave in snow, a bakery in Ballard worth waking early for. He didn’t ask about my family. He said, “When you’re ready,” and meant it. His name was Ethan, and he worked on things that flew—calculations and constraints and making certain that what goes up stays up.

He didn’t fix me. He sat with me while I fixed myself.

We married small by the lake—no speeches, no seating chart, only people who already knew the soft facts of us. No one from Dallas came because no one was invited, and there is a difference between absence and exclusion that people who love to be punished will not admit. I wasn’t sad. Happiness does not require witnesses; it requires ease.

A year later, when a nurse placed a warm bundle on my chest and asked for a name, I said “Grace,” because that is what I had finally given myself. We took her home in rain that didn’t bother asking permission. I promised her out loud what I had already promised myself in a dark room in Dallas:

You will never earn your place here. You will have it.

Sometime after Grace’s second birthday, a letter from my mother arrived—forwarded through channels I hadn’t remembered I’d left open. My dear daughter, it began in a shaky hand, and the rest was apology braided with loneliness. The Plano house sold. Samantha and Olivia not speaking. Your father with a cousin in Waco. I was wrong, she wrote. I wish you would call me Mom again.

I folded the letter. I didn’t cry. I didn’t frame it or burn it. I filed it between medical forms and a recipe card Ethan’s grandmother had mailed us—the archive of a life that had learned the difference between sentiment and surrender.

That night I sat beside Grace’s crib and whispered, “You were born from love, not silence. You never have to be remarkable to be safe.”

Rain stitched the city. The lamp threw a warm square onto the floor. I felt the past take a seat in the corner, where it would always be, and I nodded to it like a neighbor across a fence. It nodded back.

Part III — The Price of Laughter

If you had asked me years ago what retribution looks like, I might have pictured speeches in courtrooms or grand reckonings. It turns out retribution sometimes looks like nothing at all. Like a door that stays closed. Like a number that never rings. Like a Thanksgiving table that never fills.

Ethan and I built a small life with generous edges. We learned to sail badly and to apologize quickly. He taught me an engineer’s gentle reverence for constraints; I taught him a nurse’s rude insistence that pain must be acknowledged out loud. At work I created a mentorship program for new nurses because the first year is an ocean no one should cross alone. I organized a grief group on Tuesday nights for families who had no vocabulary for absence yet and borrowed ours until they did.

One evening, a mother in group said, “I didn’t know silence could be this loud,” and I thought, yes. Another said, “Everyone keeps telling me to be grateful,” and I said, “Gratitude can be a scalpel. You don’t owe anyone your organs.”

We took Grace to a small park by the water. She wore boots that made her walk like a punctuation mark and demanded I notice every dog. She looked up at me, more certainty in her than I had carried at any age, and asked, “Are you proud of me?”

“Yes,” I said. “For being you.”

“Even when I’m not good?” she asked, testing.

“Especially then,” I said, and meant it.

I didn’t know if my mother was in Texas or Tennessee or just an echo walking the rooms of houses that used to be full. Sometimes I pictured her touching the frame where Samantha’s diploma had been and the blank wall it left, the way pride vanishes when it isn’t supported by attention. Sometimes I pictured my father in a garage with a folding chair and a radio, the way men build shrines to things they didn’t know how to say.

Samantha posted less. Olivia’s paintings grew darker. Someone who had once been a neighbor sent a link to a GoFundMe I didn’t open. I had learned that some kinds of information only exist to make you a spectator in a story you chose to leave. I wasn’t that kind of audience anymore.

On a morning when fog lay like linen over the lake, I sat with coffee and realized I could think about Dallas without feeling the ache behind my breastbone. Not gone. Transformed.

At work that day a patient woke from surgery and, disoriented, asked, “Am I dead?” I smiled. “No. Alive and stubborn.” He gripped my wrist, eyes wet, and said, “Thank you for being here.” I said, “It’s my job,” then corrected myself because words matter. “It’s my honor.”

Driving home, I passed a bookstore with a sign in the window: FORGIVENESS ≠ RECONCILIATION. BOTH ARE OPTIONAL. I parked and went in to buy nothing, because sometimes you enter a place only to let it rearrange you. The clerk said, “You look like you found what you were looking for,” and I laughed because maybe I had.

That evening, after Grace fell asleep, I pulled my mother’s letter from the drawer and read it again. I didn’t write back. Not because there was nothing to say, but because I had already said the truest thing in the only language she could not mistake: I left.

I hope she eats. I hope she sleeps. I hope she learns how to apologize to herself first. I hope my father remembers how to use his hands for building. I hope my sisters love each other without triangulation, a geometry lesson we never passed as a family.

Mostly I hope the laughter they loved has softened into something that doesn’t need an object to aim at.

Part IV — A Clear Ending

Years later, on a day so bright it felt like a dare, Ethan and I sat on a bench by the lake while Grace launched a paper boat toward the far shore. The city glimmered, all steel and intention, and I thought of the first night I had pressed submit on those applications, how my hands shook and how the shaking stopped. I thought of the cake and the fork and the way a door sounds when it closes simply because it has a latch.

“Do you ever miss them?” Ethan asked, because he is the kind of man who asks questions he can hold the answers to.

“I miss a version that never existed,” I said. “And I let her go.”

A gull cut the sky. The paper boat caught a small current and moved faster than seemed possible. Grace clapped. “Look! It’s going all the way.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But going is enough.”

On Thanksgiving we set our own table. Sometimes we invited people who had nowhere else to go; sometimes we stayed in pajamas and ate pancakes shaped vaguely like leaves. We went around and said what we were grateful for, even when gratitude felt like an overlarge coat. When it was my turn I said, “I’m grateful for silence that doesn’t hurt.” Ethan said, “For the choice to stay.” Grace said, “For boats.”

When I tucked her in that night, she asked, “Grandma?” because children learn the shapes of words before the stories they hold.

“She lives far away,” I said. “We don’t see her.”

“Do you love her?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, and felt the truth of it. “And I love us more.”

She nodded, satisfied, as if I had answered a math problem. “Okay.”

After she slept, I stepped onto the balcony. Rain gathered itself in the distance. Seattle’s lights made a mirror of the lake. Somewhere I imagined a woman in Texas walking through a quiet house, touching a wall where a frame had been, holding a phone that would not ring. I imagined her sitting at a table with cake for no one and hearing the sentence she had spoken as if for the first time.

I wish you had never been born.

She had said it like a joke. She had meant it like a weapon. It had become a spell that set me free.

People think endings must explode. Most endings are a clean click. A door. A lock. A choice.

Here is mine, written clearly:

My mother said, “You shouldn’t exist,” and the table laughed. I stood, walked out, and made the sentence untrue by living well. I did not return. I did not perform forgiveness to earn applause. I built a life designed for breath.

The echo they hear now is theirs to quiet.

As for me, I am the one who stayed in the room of my own life and turned on the light.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. From Now On You’ll Eat From Your Own Groceries — My Husband Declared, But On His Birthday He Invited

From Now On You’ll Eat From Your Own Groceries — My Husband Declared, But On His Birthday He Invited Part…

CH2. My MIL Abandoned Me in a Foreign Country with My Husband, So I Made One Phone Call That Changed…

My MIL Abandoned Me in a Foreign Country with My Husband, So I Made One Phone Call That Changed… Part…

CH2. Every Christmas My Brother Left His Kids With Me — Until the Year I Finally Said “No.”

Every Christmas My Brother Left His Kids With Me — Until the Year I Finally Said “No.” Part I Have…

CH2. I Built Everything Without Her — Then My Mom Came Back Asking for Cash.

I Built Everything Without Her — Then My Mom Came Back Asking for Cash Part I — The Night I…

CH2. My Family Mocked My Scar At Reunion—Then Froze When She Learned I’m YOUNGEST SCIENTIST at INSTITUTE

My Family Mocked My Scar At Reunion—Then Froze When She Learned I’m YOUNGEST SCIENTIST at INSTITUTE Part I — The…

CH2. My Family Mocked My ‘Basement-Level Paycheck Life’ To Impress Their Guests—So I Played Along, Smiled

My Family Mocked My ‘Basement-Level Paycheck Life’ To Impress Their Guests—So I Played Along, Smiled Part I Hi, I’m Marlene….

End of content

No more pages to load