My Mom Said: ‘Stanford Is for Chelsea, Not You’ — So I Brought Out the Proof in Front of Them…

Part I — The Golden Twin

I was born eight minutes after my sister and spent the next eighteen years learning what eight minutes could cost.

Chelsea collected attention the way some people collect charms: easily, loudly, with an audience. I collected everything else—library fines I forgot to pay, late-night edits on group projects I didn’t get credit for, certificates that went straight into a drawer because there was never quite a good time to make a fuss.

At family parties, relatives angled their chairs toward her like sunflowers track the light. “Chelsea lights up a room,” Mom liked to say, and then, as if it were a compliment, “Rachel just…studies.” Dad would kiss my head on his way past and murmur, “We don’t worry about you.” It was meant as praise. It landed like an assignment.

By the time senior year rolled around, the roles had hardened: Chelsea the face, me the foundation. She chaired homecoming committees and forgot due dates. I ran tutoring sessions in the library and remembered everything. When teachers sent home warnings about missing assignments, Mom wrote outraged emails. When mine sent home praise, she filed it somewhere between the coupons and the warranty for the toaster.

Two envelopes from Stanford arrived on a Wednesday that smelled like rain. Chelsea went first, shredding hers with a flourish. The blood drained from her face. We regret to inform you. The room held its breath in solidarity. A minute later I opened mine. Congratulations.

For one suspended heartbeat, I thought maybe—just maybe—my parents would be happy for me. The look that flashed across Mom’s face wasn’t pride. It was panic. The narrative had veered off script, and she was already reaching for the teleprompter.

That night she asked me to sit at the kitchen table. She folded her hands on top of the wood the way you do when you’re about to give a lecture you think will sound like wisdom.

“Rachel,” she began, soft voice, iron core. “You need to give up your spot. Chelsea deserves Stanford more.”

Deserves. I looked down at the word “Congratulations” and felt years of AP exams, lab reports, 5 a.m. study sessions compress into a single, stupid piece of paper. “I earned it,” I said. “You know how long—”

“Chelsea has worked on herself,” Mom interrupted. “She represents us better. Interviews, alumni events, recruiting—she shines in those rooms. You don’t…you’re more…quiet.”

Dad nodded, brows drawn to neutral like Switzerland. “We have to think about what’s best for the family.”

Chelsea came down the stairs later, mascara smudged and jaw set. “Mom says you’ll let me take your place,” she announced like she was trying on the words for fit. “I knew you’d do the right thing.”

“That’s not what I said,” I managed.

But it was, in her head. It always had been.

The next week, little things shifted. Mail no longer lingered on the hall table; Dad scooped it and carried it upstairs. Mom took phone calls in the laundry room with the door closed. Chelsea started humming again, an old Disney tune that used to mean she’d talked them into ice cream before dinner.

Suspicion finally outweighed obedience. One night, when Mom was in the shower and Dad was in the garage, I opened her laptop and searched my name.

There it was: a thread of emails with Stanford’s financial aid office. “As Rachel’s mother, I’m authorized…” Attachments with my name typed at the top. Parent contribution statements. Loan forms. Scholarship disbursements redirected. A scanned signature that looked like mine if you squinted, if you wanted to believe.

I kept scrolling. An uploaded housing deposit sent from an IP address I recognized as our home. A FAFSA correction submitted at 1:11 a.m. The “student” signature: my name, my social security number, my future repositioned by someone who had always sworn she only wanted what was best for me.

My thumb hovered over the trackpad. It would have been easier to close the screen and pretend I hadn’t seen it. Easier than moving the furniture of our life.

The next day an email hit my inbox, subject line: Financial Aid Update. It looked routine. I almost deleted it. Instead, my eyes caught on the line: “As requested by Lorraine Morgan on behalf of Rachel Morgan…” There was a PDF attached. Chelsea’s tuition package, Chelsea’s housing assignment, Chelsea’s name nested inside my identifiers. I clicked through page after page until bile climbed my throat.

Downstairs, Chelsea laughed in the living room, showing Dad a Pinterest board of string lights and duvet covers. Mom’s voice floated in from the kitchen. “Yes, yes, we’re all set—Rachel is on board.”

I lay on my floor and spread the pages around me. When you print betrayal, it stops feeling like a feeling. It becomes a map you can read.

I saw the pattern then, not just in fonts and dates but in a thousand smaller things that had been training me for this moment: the family lore about who “represents us,” the whispered assessments of who “needs” what more. This wasn’t simply favoritism. This was theft.

I gathered everything into a blue folder and slid it under my bed. Paper felt heavier than blood. It was the first time in eighteen years I’d allowed myself to think: I can fight.

Part II — Freezing the Frame

I don’t have a poker face, but I’ve learned how to buy time. The next morning I skipped first period, took the bus to the library across town, and fed quarters into a pay phone that still worked if you hit it twice. If Mom had called Stanford pretending to be me, she’d have left a footprint. I was hoping to step where she’d stepped and step louder.

“Financial Aid, this is May,” a tired voice answered.

“Hi, my name is Rachel Morgan,” I said, pulse trying to kick through my throat. “I have a question about my file.”

She asked for my student ID and date of birth. I read them from the copy of my acceptance packet. Keys clacked softly in the background.

“Ah,” she said, and then hesitated. “Weren’t we just speaking with your mother this morning?”

I closed my eyes. “No,” I said. “You weren’t.”

There was a pause long enough to set a boundary. “Then I’m glad you called,” she said. “I can’t discuss details without you, but I can put a hold on any changes pending verification. If anyone calls again claiming to be you, we’ll require in-person ID. Do you want to add a note restricting access?”

“Yes.”

“Okay,” she said. “And Ms. Morgan? I’m sorry. We see this more than you think.”

I hung up, palms sweating against the cold metal handset, and walked straight to the next stop on the bus line: the police station. Because this wasn’t just a family drama. It was a crime.

At the front desk, Officer Patel recognized me from school safety week. “You okay?” she asked.

“I need to file a report,” I said. “Identity theft.”

Filing a report didn’t feel like betrayal. It felt like breath. I gave her copies of what I had. She photocopied each page, circled dates, made me sign a sworn statement. “You can place a fraud alert with the credit bureaus,” she said gently. “I know you’re young, but this is your credit. Freeze it. Here—” She slid a pamphlet across the counter. “And talk to the school counselor. You don’t have to do this alone.”

The counselor, Ms. Alvarez, had a jar of chocolate on her credenza and a way of looking at you that made you feel like you arrived capable. She skimmed my folder, frowning. “You’re not overreacting,” she said. “I’ll email Stanford’s admissions liaison and financial aid office and copy you. There’s a protocol for this. They can lock it down on their end. And Rachel?” She swallowed. “I’m sorry.”

The principal called me into her office the next day. “We’re scheduling a meeting with your parents,” she said. “We’re inviting a representative from admissions to Zoom in. You’ll bring your folder. They’ll bring their story. Let’s put everyone in one room and stop letting whispers do the talking.”

I called and froze my credit with the three bureaus. It took fifteen minutes and ended with PINs I wrote in Sharpie and taped inside my folder. I set up text alerts on my bank account. I changed every password I owned. I stopped imagining myself as the kind of person things happen to and started acting like the kind of person who makes things happen.

Chelsea grew cooler by degrees, the way a room does when someone’s been leaving the window open in January. Mom pushed a script across the dining table: “We’ll say Stanford made a mistake. We’ll say you’re taking a gap year. It’s better for our family.” I nodded and said, “Mmm,” and mentally underlined every sentence for future use.

Sometimes the bravest thing you can do in a rigged play is let them improvise while you set up lights and mics.

Part III — The Living Room Hearing

We held the meeting on a Saturday, because appearances matter in our house and Saturdays could be plausibly staged as “family time.” Dad polished the dining table. Mom set out lemon bars like that would sweeten the air. Chelsea wore a Stanford hoodie she’d bought online and a fixed smile she probably practiced in the mirror.

The principal arrived with Ms. Alvarez and a woman from Stanford Admissions—the associate director for our region, Ms. Chen, whose square glasses and clipped sentences suggested she had no patience for mythologies. She opened a laptop and clicked into a Zoom where a financial aid officer, May, and a university counsel with wary eyes appeared.

“Thank you for meeting,” Ms. Chen began. “We’re here to resolve a concern about Rachel Morgan’s file.”

Mom spoke first, tone syrupy. “We’re very proud of both our girls,” she said. “But Rachel is…considering other options. Chelsea would be such a good fit for Stanford. She’s—”

May leaned forward. “Ms. Morgan, we can’t discuss your other daughter’s file. We can discuss Rachel’s. We’ve flagged unauthorized contacts from an email address not associated with Rachel. We’ve also logged calls from a number registered to this residence where the caller identified herself as Rachel.”

“That’s impossible,” Mom said. “I’m her mother.”

“That doesn’t authorize you to sign federal loans in her name,” the counsel said evenly. “We have regulatory obligations. Fraud is not a family governance issue.”

Chelsea shot me a look, the kind we used to exchange when we were little and got caught sneaking cookies. It used to mean, help. It now meant, how dare you.

I opened my folder and set it on the table like a hymnal. Bank statements, printed emails, screenshots, the acceptance packet. “I didn’t authorize any of it,” I said, voice steady. “This is my signature.” I pointed to one. “This is not.” I pointed to another. “Here’s my report from the police. Here’s the freeze confirmation from the bureaus. Here’s the lock on my student file set by your office,” I told May. “Here’s an email you sent me confirming the hold. I’m sorry you had to do that, and thank you.”

Mom’s composure began to crack around the edges. “You can’t just take away Chelsea’s future,” she hissed, prettiness peeling off. “She shines. She represents us. Rachel, don’t do this. Don’t ruin—”

“Don’t blame me for your choices,” I said. “You promised my sister my spot before you even asked me. You signed my name to loans that would have followed me for decades. You weren’t trying to protect our family. You were trying to protect a story.”

Dad slammed his palm against the table. “I am ashamed that you would humiliate us like this in front of outsiders.”

Ms. Chen’s mouth didn’t move, but her eyes softened toward me. “Rachel,” she said, “Stanford accepted you. We want you. You earned that. We will use this call as documented confirmation that you did not authorize any third-party actions. We’ll send a written summary for you to sign. No financial activity will proceed without your explicit consent—in writing—and in-person ID will be required at orientation. We have resources if you need assistance. You are not alone.”

My throat got tight. Not from grief. From oxygen.

The university counsel turned toward the screen. “As a courtesy, we will not pursue this beyond securing Rachel’s file,” he said. “But you should be aware that federal loans and identity misuse carry penalties.”

Chelsea was crying now, mascara bleeding into little black rivers. “You don’t understand,” she told Ms. Chen. “I’m the one who can…network. Fundraise. I’m better in rooms like that. Rachel doesn’t—she doesn’t shine.”

“Then perhaps,” Ms. Chen said calmly, “you can learn to shine where you are. There are many places to succeed.”

The principal spoke softly. “Chelsea, our counselor can help you identify excellent schools that match your achievements. But we cannot build a future on someone else’s name.”

Mom stood so fast her chair skid. “If you walk out of this meeting, Rachel, don’t come back,” she said, voice low, eyes hot. It was the same ultimatum they’d used when I was seven and didn’t want to perform their chosen piano piece in front of the neighbors. It had scared me then.

It didn’t now.

“Okay,” I said, and surprised myself with how calm the word sounded.

I signed the summary Ms. Chen slid across the table. It felt like signing my own name for the first time.

Part IV — Oxygen

Packing for college felt like exhaling after holding my breath for a decade. I sold my high school desk to a neighbor through a buy-nothing group and carried boxes to the car in the late afternoon when the shadows stretched across the driveway like parentheses around the life I was leaving. Mom texted me recipes and criticisms and finally, silence. Dad handed me a bank envelope with $200 and said, “Don’t embarrass us.” I tucked the envelope into my pocket and didn’t say what I wanted to—that embarrassment is personal, and always has been.

Chelsea didn’t come to the curb when I pulled away. I typed her a paragraph the night before and deleted it. I sent instead: I hope you find the place that wants you for you. She saw it and didn’t reply. Grief comes in strange shapes; sometimes it wears your twin’s hoodie and a history you can’t fit into anymore.

Stanford’s campus smelled like eucalyptus and library dust and, on foggy mornings, the ocean breezing in like possibility. Orientation took an hour longer for me because I had to go to three windows and show my ID three times and answer the same questions three ways. It felt like being inconvenienced by safety. I was grateful for it.

My first class met under a palm outside a building older than our town. The professor wrote “Syllabi” on the board and then said, “Rules are just scaffold. We climb them to build. We don’t live on them.” I copied the sentence into my notebook and underlined it. The underlining made my hand ache and my heart loosen.

At night, I taped one thing over my desk: the acceptance letter I’d folded and unfolded until the edges softened. Not because I needed to prove it was real. Because my eyes liked landing on the word “Congratulations” when I forgot that my worth wasn’t the world’s to authorize.

Spring break came. I didn’t go home. I stayed and worked at the library circulation desk and learned the names of the morning regulars who smelled like coffee and footnotes. Mom sent a postcard of the Grand Canyon with only “We could have had a different life” scrawled on the back. I tossed it in a drawer with the rest of the might-have-beens.

In April, I got an email from Ms. Alvarez. “Can you Zoom into our senior awards night?” she wrote. “We’re giving the underclassmen a talk called ‘Advocacy and Paper Trails.’ We’d love you to speak.” I said yes. It felt right to turn a wound into a blueprint.

In June, Chelsea texted. “I’m at community college,” she wrote. “I hate it.” I typed and erased six answers that started with “You chose…” and landed on: “Transfer counselors are great. Want me to connect you with someone?” She said “No.” Then, after a beat: “I’m sorry.” It wasn’t enough. It wasn’t nothing. Both can be true at once.

The last week of freshman year, I sat on the steps outside the main quad and called May in financial aid to thank her for her kindness on that first day. “We don’t always get to see the end of stories,” she said. “Thank you for telling me how this one is going.”

When I hung up, I scrolled to the photo I’d taken of the table the day of the living room meeting—the papers, the lemon bars, Mom’s hand hovering, Chelsea’s hoodie sleeve in the corner. I didn’t save it to a revenge folder. I saved it to an album labeled “Oxygen.”

I still hear Mom’s sentence sometimes, the one she spoke steadily like a fact: “Stanford is for Chelsea, not you.” It’s a line I learned to answer, not with a scream, not with a speech, but with a portable file box and a calmly dialed phone.

Not everything gets fixed. Some things get named and then left alone. But I learned this: when a story insists you don’t belong in it, sometimes the bravest thing you can do is bring your proof into the room and keep saying your name until the mic remembers it.

At the end of sophomore year, I was walking across campus when a girl I didn’t know jogged up, breathless. “Are you Rachel?” she asked. “I’m Maya. Ms. Alvarez sent me your essay. I’m filing my own report—my uncle tried to sign a loan in my name. I thought I was crazy until I saw your story.”

“Do you have a folder?” I asked.

She lifted a blue one, dog-eared and full. “I do now.”

We sat on the grass and went through her pages. “Remember,” I told her, “they’ll call you dramatic. They’ll say it’s a misunderstanding. They’ll say you’re ruining the family. But paper doesn’t lie. And breathing isn’t betrayal.”

She nodded, eyes wet. “Thank you,” she said. “For not…disappearing.”

I smiled. “Someone tried to write me out,” I said. “I brought a pen.”

The late sun burned down between the palms. Somewhere, a bell tower tolled the hour. I folded my legs under me, tipped my face toward it, and let the light have me.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Mom Screamed: “Where Do We Sleep?!” When I Refused to Let My Brother’s Family Move In My Home

My Mom Screamed: “Where Do We Sleep?!” When I Refused to Let My Brother’s Family Move In My Home …

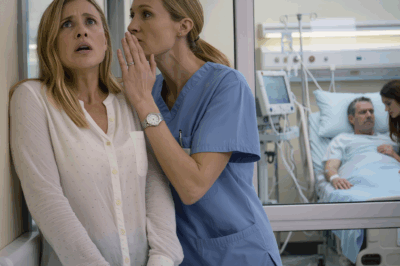

CH2. I Rushed To The ICU For My Husband. A Nurse Stopped Me: “Hide, Wait.” I Froze When I Realized Why…

I Rushed To The ICU For My Husband. A Nurse Stopped Me: “Hide, Wait.” I Froze When I Realized Why……

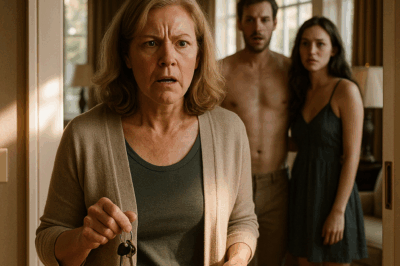

CH2. I Visited My Second Home To Rent It Out And Found My Son-In-Law There With His Mistress

I Visited My Second Home To Rent It Out And Found My Son-In-Law There With His Mistress Part 1 The…

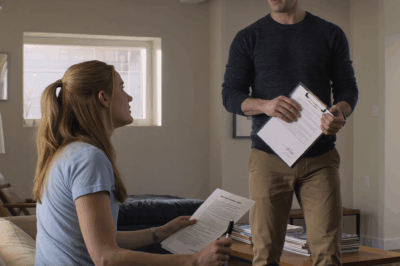

CH2. My Girlfriend Admitted: ‘I Faked Your Signature to Co-Sign a Car Loan for My Brother. You Can Handle the Cost.’ I Responded: ‘I Understand.’

My Girlfriend Admitted: “I Faked Your Signature to Co-Sign a Car Loan for My Brother. You Can Handle the Cost.”…

CH2. My Mom Changed the Locks and Told Me I Had No Home — So I Took Half the House Legally.

My Mom Changed the Locks and Told Me I Had No Home — So I Took Half the House Legally….

CH2. My Mom Said “Flights Are $1,450 Each. If You Can’t Afford It, Stay Behind” Then Charged $9,540 On Me

My Mom Said “Flights Are $1,450 Each. If You Can’t Afford It, Stay Behind” Then Charged $9,540 On Me …

End of content

No more pages to load