My Mom Handed Me A Glass Of Red Wine With A Strange Smile At My Engagement Party. It Smelled Off. I Swapped It With My Sister. Thirty Minutes Later She Collapsed And…

Part I — The Smile, The Stem, The Smell

The first thing that was wrong with the night was my mother’s smile.

It had angles. It had choreography. It did not have warmth.

She drifted through the marquee like a hostess at a banquet held in a stranger’s name, white silk skimming her calves, pearls soft against her throat. People parted for her out of habit. I watched her choose the moment — the exact slice of music, the camera angle, the mirrored glimmer of fairy lights — and then she approached me with a crystal glass cupped in both hands as if she were bringing me pieces of the moon.

“Congratulations, sweetheart.” She pressed the stem into my fingers.

The stem trembled, not from her age — she never allowed age enough room to show — but from something else. Anticipation, perhaps. Or calculation pretending to be love.

I brought the bowl to my nose the way my grandfather taught me: first the bloom, then the breath, then the wait. It was a Pinot Noir I recognized by label — too expensive for the bartender’s station, exactly priced for my mother’s performance. It should have smelled like red fruit and soft spice.

It smelled like metal under velvet.

“Thank you, Mom,” I said, smiling as if thank-you meant what it used to mean. As if Mom did, too.

Across the room, under a string of Edison bulbs, Daniel flung his head back laughing. My sister, Emma, touched his sleeve, her mouth as red as the wine and almost as shiny. They looked comfortable together.

Too comfortable.

The smile. The stem. The smell.

Somewhere beneath the lace and the rented flatware and the praise for my mother’s impeccable taste, something in me clicked into place. It was not fear. Fear is loud. This was a quiet door locking.

I turned away from my mother, wine in hand, and walked straight toward Emma.

“You look incandescent,” she whispered, leaning in to kiss my cheek. The scent of her perfume was narcotic. She had my mother’s bone structure and my father’s soft conversational cadence. She had everything I used to want.

“Try this,” I said, and lifted my glass toward her. “It’s better than what they’re serving at the bar.”

She didn’t hesitate. She never hesitated, because the world never taught her to.

She tipped the glass, throat working once, twice, three times, then handed it back empty. “Delicious,” she said, and smiled. That smile — the last one I saw before her face learned a new shape.

Thirty minutes later, under fairy lights and applause, she folded slowly, like a letter someone tore carefully down the middle.

Glasses shattered, the red on her dress became more red, the music hiccuped and died. A ring of people formed with the kind of urgency that belongs to strangers and saints. Daniel fell to his knees and called her name like an apology. My mother’s voice rose used to be roses, now thorns, while she pressed napkins to Emma’s mouth with hands that did not shake.

I stood beside the cake table, hands folded, cheek tilted toward the nearest light like a portrait. Calm, composed, unhelpful. The witness the night required.

Poison, they would say later, in a hospital corridor lit like judgment. Traces of a rare cardiac compound, they would say. Ingested minutes before collapse. Acted fast. Could have been fatal.

It wasn’t. Not for Emma.

The only thing that died that night, cleanly, without hope of resuscitation, was the lie of my mother’s love.

Part II — Before The Glass

Emma had always been the golden one. If you grow up in a house where love has a ledger, you learn fast which column your name lives in.

“Be softer,” my mother used to instruct me, as if womanhood were a lotion you forgot to apply. “You’re so intense,” she’d sigh when I brought home grades with no curves and opinions with edges.

To Emma she said, “Sit up,” and “Smile for me,” and “Yes, that one,” at The Dress shop and at fifth grade recitals and at the hairdresser who gave her a fringe that almost made my mother weep with relief. Emma was compliance in pretty packaging. I was competence in a tone my mother called disrespect.

When I met Daniel at a benefit for pediatric oncology — because God loves irony almost as much as my mother — he leaned on a cocktail table and listened like he had nothing else to do with his ears. His family owned a boutique construction company known for putting glass on things that shouldn’t have glass. He spoke about philanthropic corridors and I spoke about pediatric sedation protocols. He touched my forearm when I laughed. Everything else accelerated.

He proposed in the mantled living room of my mother’s house, because he asked her permission first and because she said yes to the moment before I did.

I believed them — him, her, the myth of us — for longer than anyone has a right to.

Until the evening steam fogged our one-bathroom mirror and Daniel’s phone lit up on the sink with solitaire and Emma’s name and a heart next to it.

I wasn’t snooping. I wasn’t even curious, which is its own kind of privilege. I was moving laundry and wiping toothpaste and checking the oven, and my hand moved to his phone like a memory.

Emma’s thread was near the top. I opened it before the part of my brain that likes to say don’t could practice its own wisdom.

Can’t wait to see you again. A hotel name. A date that fit neatly into the blank where he told me he was in a supplier meeting. Photos of bedding, a room service tray, a view straight down that only our city hotels afford. A selfie with her cheek pressed against his shoulder. A joke about my “big nurse energy” written in the language of people who have never watched a child arrest and come back.

She deserves to know someday, Emma wrote, three months into their thread. Just not now.

Someday. Not now. I closed the thread and deleted it. I wiped the phone with the tea towel, then ironed the towel with my hand as if that could smooth the outrage back into fabric.

They ended it quietly a few weeks later. He re-proposed with a ring bigger than the first and an apology thinner than air. My mother cried with such convincing weeping you could almost forget she had eyes.

“Families overcome,” she said, clasping my hands so tightly the bone sounded. “We move forward.”

We did. Toward a night with fairy lights and glasses and a smell that did not belong to wine.

Part III — The Study and The Sentence

The day before the party, I passed my mother’s study on the way to steal her stapler. The door was open a fist’s width — my mother’s life does nothing accidentally — and I had learned long ago that some doors open specifically for the daughter least likely to knock.

Her voice was low and flat, its cruelty narrowed to a blade. “Make sure she drinks it,” she said into the phone. “She’s always been dramatic. It will look like an accident if it happens fast.”

My hand froze on the door frame. I did not step inside. I did not gasp. Gasps are theater. I stood there long enough to divorce the sentence from that part of my brain that still wanted to believe it meant anything but what it meant.

If I had not smelled the wine, maybe I would have told myself later that I misheard. But your nose knows what your denial can’t.

The next day, under lights and garlands, she picked up the wrong child and learned what consequence feels like when it trips and becomes a spectacle.

Part IV — The Collapse and the Calm

Time is elastic around catastrophe. Those thirty minutes between my sister smiling at me with my death in her hand and the moment she picked the floor with her cheekbone stretched like melted sugar.

Everyone did what they have always done. My mother performed care. Daniel performed chaos. I performed restraint. The paramedics performed grace.

Emma did not die. The doctors used the precise words that can hold a family together for a few months: stable, monitoring, coma. She breathed by machine. She ate through a tube. She wore socks that said Be Brave because nurses have a sense of humor that saves lives when nothing else can.

The police called it an “open investigation.” Reporters called it “society intrigue.” My mother called it “a tragedy, of course,” and “my poor baby,” and “how could a hospital allow this,” and “we will be seeking answers” into microphones that loved the shape of her lipstick.

At home, I made tea and touched the scar on my left ring finger where a child in my care once bit down hard enough to mark me permanently. I have always loved my scars for their honesty.

I did not call my mother. I did not visit Emma until the cameras left the lobby.

When I finally slipped into the ICU at 3 a.m., I took the unoccupied chair and set my palm on the sheet next to her elbow, because touch is a language that belongs to siblings long before they share words.

“You almost drank it,” I said softly, to both of us. “And then I made sure you did.”

The machines hummed. A nurse walked in, looked at me, looked at the name on the chart, looked back, and then nodded as if we had agreed on something that had nothing to do with law.

“People think poison is dramatic,” she said, adjusting a drip. “But you’d be amazed how often it’s domestic.”

“Yes,” I said. “I would not be.”

Part V — Evidence Has Neighbors

Murder is a big word. Attempted murder is only a little smaller. Both require proof wider than family legend and deeper than intent.

I am a pediatric nurse. My religion is documentation.

The bottle of wine my mother pressed into my hand — with its crisp label and its hummed notes of spice — had traveled from a boutique vintner to a distributor to a storage room to a shelf. Somewhere between the shelf and the stemware, the seal broke and the top went back on and the smell went wrong.

The barback, who has a new baby and three jobs and an aunt who cleans houses for women like my mother, remembered seeing my mother in the staff area, “looking for napkins.” The caterer’s intern, who has a crush on a bartender and a future in journalism, remembered the moment the mother of the bride “insisted” on handling the special bottle.

Security footage is grainy until it wants a raise. The study in my mother’s house is full of framed degrees she did not earn and one camera she did not admit to the people who installed it. When the judge signed the order to permit a search, the officers took the drive out of the wall like they were handing me a baby.

Her call, the sentence about accidents—that part, ironically, was not on the recording. She had learned evasive habits of the wealthy. But her laptop was honest. Her search history was greedy. My mother had shopped for compounds by phrases. Metallic taste. Quick onset. Wine soluble. She had not thought to clear the cache because people who hire others to clean their lives forget to scrub their own fingerprints.

When they cuffed her, she fainted in an impressive arc. When she woke, she asked for lipstick and a lawyer in that order.

She sat in orange with posture that could cut fruit and called me heartless with a mouth that tried to swallow my life.

I do not like the word “vindication.” It suggests the winner is surprised. I was not surprised. I was tired.

Part VI — Inheritance Is Not Only Money

My mother’s business wasn’t hers so much as it was inertia held together by interns with clipboards. When the Board realized public relations can’t cover attempted murder––and that fiduciary duty has a longer memory than charm––they asked me to step in until the storm passed.

I said yes because sometimes the most radical act is keeping the thing you built from being run by people who tried to burn you out of your own name.

I did not tear it all down. I turned lights on in rooms my mother only ever used for show. I raised pay for the people who cleaned up the fingerprints of the wealthy and lowered corporate cards for those who liked to sign dinner bills. I sold the lake house and gave the money to a scholarship fund for kids whose mothers will never be allowed near a foundation gala. I named it Sisters Who Survive and did not explain the joke.

Daniel sent a text that began with I didn’t know and ended with I miss you. I did not reply. He married Emma quietly during one of her better months. Then he left quietly when the better months became rarer. Cowards always prefer quiet.

Emma slept. And then one day, almost exactly a year to the party, she opened her eyes.

Recovery is not a montage. It is a series of unflattering angles and indignities elevated to miracles by the people who love you in those angles. Emma’s voice arrived in syllables. Her memory came back in shards. She cried because she couldn’t tie a ponytail and because she remembered how to tie a ponytail and because she remembered why she didn’t have to tie one for a while. She could not remember the taste of wine.

My mother did not regain her footing on the white tile of the courthouse. Attempted murder carries a long sentence when evidence smells like metal. Her lawyer asked the judge for leniency on the grounds that she had “always been an attentive mother.”

The judge said, “Attentive to what.”

Emma did not attend the sentencing. I did, in a suit the color of my own sleep. My mother fixed her eyeliner in the reflection of the plexiglass. “You did this,” she said. I wanted to say, No, you did. I said, “It wasn’t even good wine.”

Humor is a bandage you keep in your pocket.

Part VII — The Confrontation That Wasn’t

The first time Emma spoke my name after the tube came out, it sounded like a question.

“Lila?”

“Not Lila,” I said. “Lila was the dog.”

She laughed and cried at the same time, which is how we learn to be people.

“I saw the video,” she whispered later, when the room was full of the low hum that happens between people who have lived inside each other’s lives deeply enough to not need words.

“What video?” I teased, because teasing is mercy.

“Me falling,” she said, half-smiling, because we make jokes about tragedy or it eats us. “I looked… good.”

“You have always loved a dramatic exit,” I said.

Then her face shifted, the humor falling like a costume. “I’m sorry,” she said, tone so small it could break your shoe if you weren’t watching where you stepped.

“For what?”

“Daniel,” she said. “The hotel. The… someday.”

We sat in that apology as if it were a church no priest could enter. She reached for my hand. Her fingers shook.

“I wanted what you had,” she said, honesty making her eyes look very young. “Or what I thought you had. Or what Mom told me I was supposed to want. I don’t know. I just know I hurt you.”

“Yes,” I said. Because cheap forgiveness is an insult.

“I don’t remember the wine,” she whispered.

“You don’t need to,” I replied. “I do.”

“I would have died,” she said.

“Yes.”

“I’m alive because you made me drink it,” she said, half-smiling again, because tragedy is a twin to grace and sometimes you get to choose which parent it resembles.

“You are alive because the compound acted fast and the paramedics got there faster and because the nurse who hates her supervisor’s playlist loves her job,” I said. “You are alive because the world is inconvenient to murderers.”

“You still love me?” she asked, a child and a woman in the same mouth.

“Yes,” I said. “But I love me, too.”

Part VIII — After The Glass

People like stories that end at weddings and jail cells. They like to believe that one ceremony and one sentence can clean a house. I have cleaned houses professionally. It is never one swipe.

My mother is three years into a sentence that reads like a math problem. She reads books. She writes letters I do not return. She has found God again, which is convenient for people who need to believe that someone gets them even when nobody else should. I send money to the commissary because I do not believe in starving anyone. That is where my mercy ends.

Daniel moved to a city where nobody knows how he laughs. Sometimes I see him in photographs making faces I recognize on other men who thought they were irreplaceable. He dates women who don’t know what metallic wine smells like. He is not my problem. I hope he is someone else’s lesson.

Emma walks with a slight hitch that she says makes her look interesting. She went back to school to learn speech therapy and now spends hours coaxing sounds out of mouths that forgot how to make them. Sometimes we go to the beach, and she stands at the edge of the water and cries and I do not ask her why.

On the anniversary of the party, we held a different kind of celebration. We set tables in a hospital cafeteria and served good wine and bad coffee and told the night shift they were the reason anyone makes it to morning. We called it The Survivors’ Banquet, and we made my mother’s least favorite florist deliver bouquets to nurses whose names nobody ever writes down. We hung a sign that said, TO THE PEOPLE WHO MAKE ACCIDENTS INCONVENIENT.

Sometimes I sit in the ICU at 3 a.m. because the lights there feel like honesty and the machines remind you that bodies are smaller than we think and larger than we’re told. I bring a thermos and leave it at the desk with a note: For the nurse who will keep someone’s daughter alive tonight. They never ask who left it. They don’t need to.

Part IX — Coda: The Glass Is Still There

The night my mother handed me the wine, I thought the choice was simple: drink or don’t. It was not. There was a third choice—hand it to the person who had always been offered what was meant for me and watch the world prove it should never have been for anyone.

Sometimes people ask me if I feel guilty.

Guilt is an instrument my mother taught me how to play and then demanded an encore. I set it down.

I feel other things. I feel the warm metallic press of a child’s palm in recovery. I feel the stubborn joy of breakfast with the sister who learned to chew air before she learned to chew toast again. I feel the satisfaction of a ledger balanced by truth and the humor of men who think their appetites are new.

I also feel the glass in my hand. Still. Always. Clear. Clean. Full of something that smells like cinnamon and plum and mercy.

I do not drink. I lift it to the light and watch it catch on the scar in my sister’s left eyebrow — the one she doesn’t see when she doesn’t look — and I say one word like a toast to nobody:

“Survive.”

And somewhere a nurse laughs at a joke and a paramedic finishes paperwork and a judge signs her name and a mother in a cell opens a book she should have read before she learned how to phone the wrong person, and a girl who is not yet a woman smells wine that is not quite wine and listens to her body whisper no.

This time she puts the glass down. This time she doesn’t need me to hand it to anybody. This time the party goes on after the lights go up, and the person in white goes home and hangs her dress without blood on it, and her mother’s smile stays off.

Not warm. Not proud. Just gone.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not worth the trouble,” she said. I cleaned toilets for money. Monday, a detective found me: “Your real father in Germany spent millions searching for you. He left his automobile empire worth $2.1 billion -to claim it, you have 72 hours to your family’s darkest secret”

After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not…

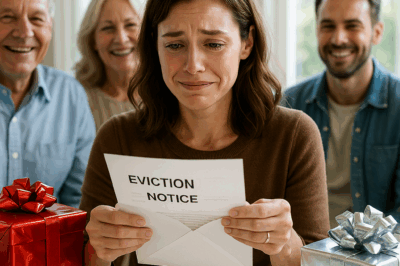

CH2. On My Birthday, My Family Gave Me A ‘Special’ Present. When I Opened It, It Was an Eviction Notice for My Own House. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding Day…

My Family Gave Me an Eviction Notice on My Birthday. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding…

CH2. My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed…

My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent It to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed… …

CH2. At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake

At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake Part I — The Invitation With a…

CH2. My Family Told My Sister’s Kids To Eat First And Told My Kids To Wait To Share The Crumbs.

My Family Told My Sister’s Kids To Eat First And Told My Kids To Wait To Share The Crumbs …

CH2. Half a Heart, Whole Courage – Rita’s Miracle Journey

On Valentine’s Day, while the world celebrated love, our little girl was fighting for her life. Rita underwent her second…

End of content

No more pages to load