My grandson whispered of their cruelty. I’m an antique dealer. I made one call: “It’s cleanup time.”

Part I

Finn, it’s okay now. Grandpa’s here.

The knock was not a knock but a heartbeat against wood, a frantic thudding that traveled through the old bones of my shop and into my own. I had been awake—men like me sleep lightly, even after the world believes we’ve retired from it. I crossed the dim showroom where lamplight pooled on brass and glass, where the faces of a hundred clocks watched like witnesses who had agreed to stay silent. I unlatched the back door and found a child-shaped tremor on my stoop.

Finn. Six years of small breaths and skinned knees, my grandson, wrapped in rain and fever. He was shaking as though a winter had crawled inside him. His pajamas clung to him like a drowned flag; his hair stuck in thorns to his brow. I lifted him before words could fail us both. His skin burned. His lips moved, but shame was a frost on his mouth.

“Grandpa, I’m sorry. I was bad. That’s why Grandma and Daddy—”

“No,” I said, the word definite as a lock turning. “No, my boy.”

I swaddled him in a towel that smelled of cedar and laundry soap, a clean scent I had hoarded against nights like this, and I carried him through the showroom’s amber quiet to the cot behind the curtain. My hands did not tremble. Ghosts do not tremble. They only remember how, and then choose not to.

You will have heard my other name, or perhaps you have only felt it in rooms where the air changes without a breeze. Ghost. A shadow within shadows, a rumor even to those who sell rumors for a salary. For decades, I moved pieces on boards that no one else could see. I signed my name on the undersides of events with the ink of absence. Coups toppled as if the wind had developed preferences. Men richer than countries died of accidents that did not look like accidents. I was the tool governments pretend they never needed.

Once, in a city that screamed with color and decay, I approached the throne of a cartel king by walking across the backs of his lesser monsters. I found my way in through a lieutenant with a cracked smile and a daughter whose laugh had the bell tone of a church service. He became my informant. He became my escape hatch. And when the extract came, wrapped in sirens and speed, I left him. The mission was clean. The man’s death was not. Some debts you can only pay by becoming someone else.

So I became Cyrus: antique dealer, hand steady on a magnifying loupe; a man who could tell you the century a hinge was forged by the way it breathed when you opened it. I put my tools in a casket and buried them beneath the shop. I told my son, Julian, nothing. He grew up under my thin fiction as under a thrift-store lamp: warm enough, never blinding. He married a beautiful woman with eyes the exact color of a polished blade. Adora, she called herself—later I would learn to pronounce the truth of her name: Isidora. She smiled like a promise and carried her father’s ghost in her teeth.

Finn whimpered in his fever sleep. I set a kettle on the hotplate, spooned honey into a cup so the sweetness would already be waiting. When he woke, I pressed the cup to his mouth and let him sip, his throat working with the stubborn determination of children and soldiers. “It’s okay now,” I repeated, and in my voice there were two men: Cyrus, who meant to make soup and fold small shirts; and Ghost, who meant to make something much larger disappear.

“Grandpa,” Finn whispered, “I was bad. Mommy said I… I ruined everything.”

“She was wrong,” I said. “She will never be right about you.”

He asked nothing more. Meaning finds its own level when it is tired. He slept. I tucked the blanket tight around him, touched his forehead with the back of my fingers, and descended.

The hidden room is not a cliché. It is a strategy. Behind the wall of clocks—French carriage pieces that winked like conspirators, iron-cased workshop clocks that thudded like old hearts—I pressed a sequence that would mean nothing to anyone who had not learned to count in the way I was taught: by rhythm, by pain, by memory. Wood slid against wood. Cold air breathed out of the dark. The room still wore the dust of years, but under the dust slept a modernity so clean it felt like a blade.

I sat before the console as a priest sits before an altar he swore he would never approach again. The line to Langley was as quiet as a confession booth. It rang three times. Then a voice I had once heard through comms over deserts and over oceans arrived in my ear and did not pretend to be surprised.

“Ghost,” the deputy director said, speaking a name he was careful never to write. “Calling from the grave?”

“Calling from home,” I said. “I need everything on Isidora López. Recent holdings, contacts, movements, affiliations. And I need it yesterday.”

He exhaled. He still did that when the stakes leaned across a table to stare at him. “You’re choosing violence on a Sunday night, old friend.”

“I’m choosing a child,” I said. “Get me what I ask.”

“I’ll have to log the request in a place that does not technically exist,” he said, dry as old paper. “Give me two hours.”

“Give me one.”

Silence that meant yes. The line went dead like an eye closing. I got up, wiped a ring of dust from the edge of the worktop with the side of my hand, and felt something I’d promised I would never feel again: the old joy that comes from having an enemy worthy of my attention.

Above me, the shop returned to its illusion as a place where things merely wait to be purchased. Below, the machines began to purr like cats that had forgiven me for abandoning them. The feed came like rain on a metal roof: lines of data I translated by touch. Names surfaced and sank. Photographs snapped into place and then away. I asked for more; it came. The deputy’s people always did love an impossible request.

Isidora had not just married my son; she had married his company. Julian, with his boyish optimism and self-made swagger, had built a shipping operation capable of slipping between regulations like a fish between rocks. He called it logistics because the world had made that word respectable. Isidora called it a vein, and she knew what pulsed in veins. The cartel her father had served was not dead; it had simply learned how to sit still until the cameras moved away. It had a new daughter now, and she honored her ghost by feeding his old animal.

Drugs were not the point, not anymore. The point was rarer, more fashionable, and dressed in rhetoric that sounded like wealth. Parrots who would never again know trees. Snakes scaled like living jewelry. Frogs small as coins and bright as warning lights. They were tucked into crates that read MACHINE PARTS and MEDICAL EQUIPMENT and DELICATE—HANDLE WITH CARE. They were freight misnamed as freight. They were breath measured in invoices. Finn’s mother sold gleam to gleam.

There are lines in me that even the work could never cross. Children and animals are the two lines. I will sit in silence while men lose the lives they have paid for with their cruelty, but I will not watch an innocent suffocate because a rich man wants a conversation piece. A heat rose in me that had nothing to do with anger and everything to do with arithmetic. Numbers add up. Debts must be balanced.

I triangulated chatter from ports that liked to pretend they were too busy to notice their own complicity. I paid favors with favors. Antique dealers hear things. Men who buy old weapons like to talk about their new ones. Women who collect silver love to collect secrets. By dawn, I had the route. By noon, I had the hour. A week from now, under a weather pattern that promised to complicate both conscience and cameras, Warehouse Seven at the docks would receive a container that contained the last dose of my tolerance: dendrobatids, poison dart frogs, harvested by hands that feared the jungle less than they feared empty wallets, packaged alive for buyers who enjoyed the thrill of danger as long as it never touched them.

I fed my timing to Langley. “You’ll get your press conference later,” I told the deputy director. “For now, I need a DEA tactical unit to act like a wall. Not a spear. No one moves until I say.”

“You’re going in,” he said. Not a question. An old comprehension.

“I’m going in.”

“You’re seventy.”

“I’m inevitable.”

He made a sound that could have been a laugh if the world were gentler. “All right, Ghost. I’ll plant my men in the dark corners. But if you go down—”

“Then your men can switch on the lights and claim they tripped over me while performing their heroic duties.”

“Still insufferable,” he said. “Still useful.”

The week was a long breath held under water. I lived by habit: oiling hinges, answering the questions of men who wanted to know whether a clock’s face had been refinished. Finn’s fever slid away under soups and stories. He slept the hard sleep of the rescued. When he was awake, he watched me in a new way, as if I had changed the color of my shirt without changing the shirt. “Grandpa,” he said once, small voice testing the shape of courage, “are we safe?”

“We are safer than we were yesterday,” I said. It was true. I am careful with truth in front of children. It is a tool that, once blunted, cannot be sharpened without cutting something.

At night, when the shop slept, I descended and woke the part of myself that knows how to move without leaving fingerprints on air. The gear felt like a language I had once spoken fluently and had not forgotten: night optics that turned chaos into a topography; comms that sat in the ear like a secret you chose to keep; a suit that treated to the body as both armor and apology. I stretched until my joints stopped arguing. I drilled until muscle memory returned like a friend I had wronged but who had decided to forgive me for one more night.

The storm came on schedule. The docks liked the cover; the water liked the drama. Warehouse Seven squatted at the edge of the world like a thought you should have had earlier. From the roof, the rain softened the sound of my arrival. I lay along the spine of the building and watched men I had once taught my son to avoid. Julian stood among them, his posture both confident and borrowed. He had my chin and his mother’s impatience. He did not have what he needed most, but then again, what child does?

The container rattled up and kissed the concrete. Doors opened on careful men with careful gloves. Cases were unloaded: gray and precise, the kind doctors would trust. A convoy of cars ghosted in, their headlights off, their interiors full of men who liked the smell of money until it mixed with fear and became their least favorite cologne. I counted them like beads on a rosary: one, two, three, four. I asked the night to hold still. It did.

The exchange began not with words but with eye contact, with the small nods of men confirming that the world was still functioning in the way they preferred it to. A briefcase flashed like a fish belly in a net. A case of frogs sat like a heartbeat in a box. I moved.

Glass cracked like ice as I slipped through the skylight’s throat. Gravity made no sound. My boots touched beam and then concrete and then they did not. I became a rumor of movement among stacks of inventory and excuses. “All units,” I whispered into a line that existed only for those who had been invited. “Seal the exits. Do not engage unless I fail.”

“You are not allowed to fail,” the deputy director said in my ear, and I ignored the sentiment as I have ignored gods.

Darkness is an ally if you’ve learned to read it. I killed the power and it bloomed. Men became the shape of their breathing. They flinched in patterns that told stories. Some shouted. Some fell silent, hoping silence could make them smaller than bullets. Gunfire started as it always does: too loud, too early. They shot at shadows and hit each other. Fear is terrible at aim.

I wove through them, a surgeon moving through bad choices. I do not take lives casually anymore. I am too old to carry the weight casually. So I took hands, elbows, knees. I took balance and comfort. I left pain and consciousness, gifts a court would understand. Bodies thumped down into a choreography of regret. Men whose names their mothers had said softly lay whispering what sounded like prayers and were actually curses.

Through the green lens of my night, I found the boy I had raised into a man and then let the world raise into something else. Julian stared as if the dark were a story that had suddenly learned to speak his language. He fired twice at where he thought I might have been. He missed and hit his ally in the thigh. Chaos taught him humility. He dropped the gun without meaning to.

“Dad?” he said when I stood in front of him, my goggles up, my face bare, my old name bright enough to blind him. “Dad, why?”

“Because you said yes to monsters,” I said, and heard the softness in my own voice and did not hate it. “Because you failed at the only job a man cannot fail at.” I struck him hard enough to give him sleep without dreams. He slid to the floor and looked, for the first time since he was six, like a child. I wanted to pick him up. I did not.

Lights blossomed. The DEA unit had defined the perimeter so neatly you could have rolled pastry on it. They entered with their weapons pointed at the ground, the way professionals who are not afraid can afford to enter. The deputy director’s gray suit looked indecent inside a place like that, like a bird inside a slaughterhouse. He nodded at me as if we were two men who had discussed golf.

“Still as dirty as ever,” he said.

“Still as efficient as required,” I said. “Is she secured?”

“Lifted her from her hotel before she finished her last drink,” he said. “Your daughter-in-law is less poetic without a stage.”

“Good,” I said. “Collect the Yakuza and leave a ghost story in this place.”

“You’re leaving already?”

I was. I always do. “You’ll log your heroics and tell Congress it was teamwork,” I said. “And if they ask about me, give them a story about a draft through a door someone forgot to close.”

“You owe me a favor,” he said, because men like us cannot end a night without placing something on a scale.

“I’ll pay,” I said, because men like us know scales never go away.

I walked outside into the rain that had nowhere else to be and felt the weird peace that only follows an ending. The world was not clean. It was, temporarily, cleaner. It would have to be enough.

The aftermath did what aftermaths do: it hid inside acronyms and folders that could not be photographed. The arrests did not exist on paper until the papers that mattered decided to acknowledge them. The frogs went back to the jungle their bodies resembled but could never truly explain. Somewhere in a hotel room, a woman who had believed her anger could be a crown learned that crowns are merely circles that become collars when tightened.

I returned to my shop and boiled water. Finn woke as if the night had tapped him on the shoulder and told him to, and I gave him toast with honey and a story that sounded like any other bedtime story: the kind where bad men get lost in their own darkness and good men find a door. He recovered. Children are resilient, people say, as if it were a compliment. It is not. It is an indictment of how much we require of them.

Days reassembled. The shop resumed its ritual of dusting and negotiation. Finn’s lessons grew into a small schoolroom in the back, maps on the wall and a globe that spun continents like slow coins. “Where’s Colombia?” he asked one afternoon, his finger blunting the edges of the Pacific.

“Here,” I said, guiding him to the green that sits like a thought in the middle of South America. “A faraway country with frogs so beautiful they have to warn you about themselves.”

“Even though they’re poisonous, they’re beautiful?”

“Especially then,” I said. “Remember that, Finn. Beauty is often a mask. Learn to listen to the breath beneath it.”

He nodded the way children nod when they file words into drawers they will not open for years. The bell chimed.

The man who entered had hair so neat it looked ironed and eyes that had looked at too many dossiers to be fooled by civilian lighting. He wandered a display of pocket watches he had no intention of buying and then found me with the inevitable aim of a hawk. “Mr. Cyrus,” he said, which was polite of him. “May I speak with you about your grandson?”

We sat at the scarred table in the back while Finn arranged a fleet of wooden ships and sent them across the map’s Atlantic, stopping generously to imagine rescue missions. The man placed a folder on the table and did not slide it toward me like a bribe. He simply let it occupy space like a second person. I opened it and found graphs and paragraphs written by people who trusted their own metrics more than they trusted their beds. Intelligence scores high enough to make a recruiter salivate. Behavioral notes that could have been mistaken for compliments if they had not been labeled. Heritage, the file said, a cold word for blood.

“We can give him the best education,” the man said, a salesman forced by circumstance to wear a patriot’s costume. “His future is his own, of course. But talent wants duty the way thirst wants water.”

I looked at his eyes the way I used to look at photographs of buildings I needed to enter: searching for the first weakness. “No,” I said.

He did not pretend to be offended. He let the word sit between us until it cooled. “Not the wisest decision,” he said. “For him. For the country.”

“Perhaps,” I said. “But wisdom is sometimes just fear dressed in a tie. I will raise him. You will not. If the country needs him when he is a man, it can ask him like a man. It cannot take a boy.”

He stood, knowing that victories today become losses tomorrow and arriving anyway to measure them. “We’ll be in touch,” he said, as if the phrase contained kindness. It did not. He left. The bell tinkled as if a small bird had flown into the room and realized it could not stay.

That night I watched Finn sleep and understood the scale of the war I had just declared. A nation is a large animal; it does not like its food taken from its mouth. But the animal that is a grandfather is larger than the map suggests. I took down an old map and laid it across the table like a tablecloth for a last supper. Red dots like spilled wine marked the places where Cyrus died and Ghost rose and vice versa. Safe houses that contained cash, identities, medicines, patience. A chain of small doors in a world that likes big ones.

We would go. Not because I feared men with folders, but because I remembered how boredom can become a tactic in a child’s life, how monotony can be mistaken for safety until safety fails by being predictable. I would teach Finn the geography of escape as a form of literacy. I would teach him that vanishing is not surrender if you reappear stronger.

I packed while the shop still wore its clothes. Passports. Burners. Photographs you cannot replace even if you tell yourself you can. I wrote a letter to my son that began with a sentence I hated: I did what you should have done. I put the letter in a drawer and did not leave it. He would not be the one to find it. I left a notice with the landlord that read VACATED and meant more than it said. I took only three clocks: one simple, one ugly, one perfect. Time should never be a collection; it should be a reminder.

I woke Finn before dawn. He sat up with a start and then calmed when he saw my face. “Adventure?” he asked, the way a boy asks for permission to believe.

“Long journey,” I said. “We’re going to see the world’s forgotten treasures.”

“Will we bring them home?”

“We will learn what home means,” I said, because truth is a carriage that must be driven carefully with children inside.

He dressed in layers. I poured the last of the coffee and left the cup in the sink as if that were a ritual that could bless our leaving. Moonlight clung to the shop windowpanes like a second skin. Finn’s hand was small in mine, a bird that had decided I was a reasonable tree. I squeezed once, not to hold him, but to tell him that I would not let go without telling him why.

We stepped into the alley. The city had not woken yet; it was a face before makeup. I locked the back door and let the key rest on the stoop where no one would think to look for it. The sign in the front window still said OPEN in the obedient optimism of retail. By noon, a rumor would be going around that Cyrus had finally gone to Florida like all old men who sell things. By evening, people would be telling a different rumor: that they had always suspected I was not what I said I was. By morning, there would be someone else polishing brass in a different shop and believing the world could be convinced to be gentle if you spoke to it softly enough.

We turned the corner. The car waited, anonymous as a heartbeat. I buckled Finn in, because rituals matter, and slid behind the wheel. The road ahead was only a roll of asphalt, but the air felt wider, as if the map had agreed to become a story instead of a set of instructions. I checked the mirror, a habit I indulge the way old men indulge scotch. The street lay empty. The first light of day thought about showing its face, reconsidered, and then did.

We drove. Behind us, my shop disappeared. Not burned, not smashed, not erased. It simply returned to the material of which all places are made: memory and brick and a ledger that will never balance. I did not look back again. Ghosts do not look back. They carry forward what they must, and they set down what would break them if they didn’t.

“Grandpa,” Finn said, his voice unafraid now that motion had become our shelter, “are we going to the jungle?”

“One day,” I said. “We’ll stand very still and listen to frogs practicing survival. We’ll let them keep their secrets.”

“Will we be like them?”

“We will be better,” I said. “We will walk in the light and know how to vanish if the light grows cruel.”

He considered that, then nodded—as if I had told him the rules of a simple game: step here, not there; look up when you forget the feel of your own feet.

The road unwound. Somewhere, a deputy director crossed a favor off a list and added two more in its place. Somewhere, a woman with a beautiful name learned how ugly a cell can be when a mirror is not included. Somewhere, a frightened man signed a cooperation agreement and learned the new math of regret. And somewhere, deeper than maps and higher than satellites, a child slept, woke, and laughed because the day had finally remembered how to be kind.

I drove. The car hummed. Beside me, a boy looked out the window and saw a world he had not yet learned to fear. I would teach him to fear it precisely and to love it anyway. That was my final mission. My true mission. I would be a ghost again—not to kill in the name of a flag, but to shepherd one small life past the traps that men like me had built.

Morning finally unfolded. Light poured over the road, over the dashboard, over Finn’s face. It did not ask permission. It never does. He raised his hand to it, palm open, as if catching something invisible and rare. “It’s warm,” he said, amazed, as though warmth were a new invention.

“It is,” I said. “Remember this.”

He did. And so did I.

Part II

The first safe house sat above a bakery that woke before the sun and forgave all who came to it. The smell of bread hid other smells: oil, steel, the electricity of quiet. The landlord remembered me as a traveling clocksmith with an irregular schedule and an even more irregular approach to rent, which is to say: I paid in advance and asked no questions. He handed me the key with both hands and the solemnity of a coronation. The rooms were small and clean. The bed accepted our weight like a promise kept.

Finn took inventory without knowing he was taking inventory. He opened drawers and made lists in his head. He discovered a tin box that contained marbles and believed, for one hour, that marbles were the answer to loneliness. He discovered the view from the fire escape and believed, for one afternoon, that fire escapes were ladders to a better story. He lay on the rug with a book about explorers whose portraits made them look stern and foolish and brave. He traced the coastlines with his finger and practiced the only magic I trust: attention.

We stayed three days. I bought him shoes that would not betray us by squeaking. I bought him a jacket with pockets big enough to hide a compass and a candy bar. I bought us time by paying the landlord for a month and promising to stay less. On the fourth dawn, I woke him early and we moved, because movement is a vitamin.

The second house was not a house but a room above a garage where a man repaired motorcycles and confessions. He liked to talk, which made him perfect camouflage. People who talk are interpreted as harmless. I fixed his clock for free; he called me friend without needing to understand what that meant. Finn watched the bikes and learned another language: torque, ratio, spark. He liked the smell of gasoline in the same way he liked thunder—a little, not a lot.

At night, I taught him to pick locks. Not because I wanted him to love trespass, but because I wanted him to love competence. “Rules and doors are different things,” I told him. “Respect rules. Defeat doors.” He smiled and made the pick dance. Children like being told the truth in sentences that fit in their mouths.

The recruiter returned before we expected him to, which is always how they return. Not to the shop we’d shed like a skin, but to a place we’d left no footprint in—because the Agency does not require footprints to follow you; it requires only a memory and a reason. He did not knock on a door. He called a number that no longer existed and left a message in the only place I still checked: the deputy director’s old courtesy, a voicemail channel I’d once used to say I was not dead. The message was brief and clean: We can protect him by training him. The world will not be kind to what he is.

The world is never kind to what any child is. I deleted the message and built another layer into our route.

We crossed borders under different names and the same sky. Airports are machines that pretend to be cities; if you speak their language and keep your sadness folded small, they will not notice you. Finn collected stamps as other children collect baseball cards. He learned to keep his eyes soft. He learned to listen to footsteps. He learned, most of all, the difference between running away and moving toward.

We found an island where the air tasted of salt and entrepreneurship. The safe house there had walls that remembered music. Here I let us rest. A child cannot grow on strategy alone; he requires boredom and the small troubles of everyday life. Finn attended a local school under a name that fit him like a fresh shirt. He learned to multiply with a pencil that stained his fingers gray. He learned a language in which please and thank you occupy the same part of the mouth. He learned to fight a boy who mocked his shoes, and then to shake the boy’s hand when the principal walked in, and then to break the boy’s nose—not that week, not that month, but when the boy spit on a smaller child with a face like a question mark. I did not scold him. I taught him first aid.

In the evening we sat on the roof and watched planes draw white lines in a blue so blue it bordered on violence. “Do you miss Grandma?” he asked. An arrow that curved midair and still found its mark.

“I miss the person your father used to be when she sat near him,” I said. “I miss the person I used to be when I believed I could give him everything he needed.”

“Can a person be two things?”

“They can be ten. The trick is to make sure the right one drives.”

He accepted that. He had learned to trust the way my answers did not pander. He leaned on me, a weight I would carry until I could not, and after that I would find a way to carry it anyway.

News reached us sometimes, like messages in bottles washed up by storms we had not sailed through. Isidora’s name appeared in no paper I believed. That meant she had not been freed. It also meant she had not learned the luxury of admission. Julian’s name did not appear because it could not. He existed in the gray place where men go when the state is both ashamed and proud of them. I wrote to him only once, on a sheet of paper that I then fed to a fire after reading it aloud to no one. “You are still my son,” I said into the smoke. “You are still the boy who cried at the sight of an injured bird. Learn to be that boy again, but this time do not look away.”

The deputy director found me in a park in a city of canals and bicycles. He sat beside me like a tourist going about his tourist business, which in his case was treason against loneliness. “You’ve covered a lot of ground,” he said, tearing a piece of bread for the pigeons and not feeding them.

“Ground is safer than walls,” I said.

“How is the boy?”

“Learning the map of himself,” I said. “I won’t let you draw it for him.”

“I wouldn’t try,” he said, surprising me with a gentleness I had forgotten he could deploy. “But the world will draw it. If he is not holding the pencil, someone else will.”

“He will hold the pencil,” I said. “And the eraser.”

We watched the water for a while, the way men do when they do not want to count the things that cannot be counted. “You know,” he finally said, “if I wanted to take him, I wouldn’t send a recruiter with nice shoes. I’d send a court order and a team who have never met the word please.”

“You haven’t,” I said, “because you know what I would do next.”

He smiled then, weary and fond. “Yes,” he said. “And I’m too old to bury friends.”

“We’re not friends,” I said, because it felt safer to land that punch than any other. “We’re men who mastered the same bad art.”

“That makes us kin,” he said. “Of a sort.”

He left me with a piece of advice disguised as disdain. “He’s not you,” he said. “Thank God. Raise him accordingly.”

We moved again. In South America I taught Finn how to walk in a jungle without teaching the jungle to notice him. We listened to frogs practicing their warning songs. We watched a poison so bright it could have been a toy. “Why do they show their danger?” he asked. “Shouldn’t they hide it?”

“Because some truths keep you alive only when you say them loudly,” I said. “And because they do not mistake their beauty for permission.”

We met men who had known his grandmother when she was young and fierce and a better liar than any of us. We met women who had never been asked whether they wanted to be fierce and became so anyway. We learned the names of trees that hold their water like a secret. We learned that danger looks like glamour until you are close enough to touch it, and then it looks like rot.

In Asia I taught him to sit so still the air forgot we existed. He learned to break a wrist and to heal one. He learned the mathematics of distance: how a meter can be nothing when you are walking and eternity when you are running. He learned to shop for vegetables in a market full of knives and not see a single knife as a threat because his eyes were doing the work his hands did not have to.

In Europe I taught him to disappear into crowds without becoming one of them. We stood in museums and practiced a quiet that was not reverence but respect. He preferred paintings where people were caught doing small tasks—pouring milk, mending nets. He disliked saints unless they looked tired. He touched the air in front of a Caravaggio as if it could bruise.

And always, when the day ended, we returned to the school that familiar objects make. A kettle. Two cups. A pan that forgave us our impatience. A book with a crease in the right place. A deck of cards that unbent from shuffles like a spine that refused to stiffen. He did his arithmetic with the same expression he used to do his push-ups: uncomplaining, literal, stubborn. I corrected him gently when he was sloppy. I praised him when he was precise. I refused to make him perform. The world would ask enough of him later.

Once—only once—I dreamed I had kept my shop. In the dream, the bell rang and kept ringing until even the clocks looked embarrassed. I woke with my hands curled into fists and uncurled them with the same patience I used to teach him to tie his shoes. Regret is a country that sends you postcards even when you refuse to give it your address.

Time moved in its usual fashion: quickly, then not at all, then quickly again. And then the letter came that was not a letter but a coded message that could have been junk if you did not know what it meant. It was from a friend I had thought dead—not dead in the literal sense but dead to courage. He whispered an alert in my ear through ink: someone in the Agency wanted a trophy. They had lost too many people to boredom and wanted to pin a new Ghost to a board. Finn’s file had become a story in a room where stories become orders.

I did not tell Finn. Children deserve truths measured to their hands, not ours. I did not change our route because panic is louder than prudence. I did what I always do: I made a plan that looked like a rhythm so it would not irritate the gods.

It happened in a border town that pretended it wasn’t a border town, just a collection of streets accidentally placed near each other. The men they sent were good. Men with quiet shoes and the kind of faces that do not appear in photographs because cameras turn away. They waited outside the school until Finn came out with his backpack riding high, the way I taught him. It was late afternoon, the hour when shadows lengthen and make you think of stories you might one day tell.

The first one stepped into him by mistake, a shoulder brush. The second one apologized and made a show of bending to pick up a dropped book. The third one reached and found he had grabbed a wrist that had learned to be a word. Finn turned. The move he used was a simple poem: pivot, outside line, leverage. The man’s wrist decided it preferred not to exist. He yelped like a dog stepping on glass. The second one reached again and found nothing because Finn was not there anymore. The first one touched his ear and said something quiet into it that meant abort.

I watched from the café across the street where I had been pretending to read the paper. Pretending is a skill everyone should learn. I let them retreat. I paid the bill. I bought three pastries we did not need. We walked home in a geometry that did not interest anyone with a camera. “You okay?” I asked, the way a man asks for a weather report when the clouds are ripped and obvious.

“Yes,” he said, and then after a second, “No.”

“Which will it be later?”

“Yes,” he said. “I will be okay.”

“Good,” I said. “Because tonight we pack light.”

We left before sunset, which I dislike. I prefer night because it is honest about what it is hiding. Dusk is a liar. But we moved anyway, because sometimes the math insists. I made a mistake—the first in a long time. I called the deputy director from a number I did not care to burn and said a sentence I had not planned to say.

“You are not to send them again,” I said.

He did not pretend. “I didn’t.”

“Then leash your ambitious children.”

“I will,” he said, and I believed him because men of our generation honor certain leashes.

Finn slept in the backseat and dreamed of frogs that did not forgive. I drove and made peace again with the fact that I had built a life in which the people I trusted were men who regularly sat at tables where trust was a menu item.

On a mountain road that curled like thought, I pulled over and turned off the engine. Stars threw themselves at the windshield and stuck. Finn woke with the tender confusion of a child who discovers that sleep does not cancel the world. “Are we okay?” he asked, and it could have been a prayer.

“We are,” I said. “And we are tired.”

“Tired is okay,” he decided, and drifted down again.

I left the car and stood in air so clear you could see the shape of silence. I am not a man for extravagant promises. I have kept too many small ones to believe in their larger cousins. But I made one then—to the dark, to the stars, to the boy breathing in the backseat, to the men who had taught me how to disappear, to the woman who had taught me how hatred can be beautiful until it bites you and refuses to let go.

I will not make him me.

The wind was not interested in my vow. It had mountains to worry about. I returned to the car.

Dawn met us in a town that had agreed to have a market that day. We ate tamales with our fingers and let salsa recalibrate our nerves. Finn bought a wooden whistle with a snake carved along its length and played it until a woman laughed and said the snake would get dizzy. He apologized politely to the snake. He has a good heart.

We rented a room above a shop where a woman sold dresses that would have made kings uncomfortable. The window looked out on a square where dogs negotiated their territory with the repetitive eloquence of politicians. I slept. Even ghosts must sleep.

When I woke, Finn was sitting by the window with his whistle in his lap and a question on his face. “Grandpa,” he said, “what is a mission?”

“A line you draw from where you are to where you have to be,” I said. “And then you walk it, even if you can’t see the end.”

“Is this our mission?”

“It is our life,” I said. “Which is the same thing when you do it on purpose.”

He nodded and put the whistle back to his mouth and invented a tune that sounded like a child trying to imitate birds and succeeding enough to make one turn its head.

We stayed in that town until the woman who sold dresses decided we were safe to like. She told us secrets that were not useful but were beautiful. I bought Finn a hat and taught him to wear it with courage. We left when the map told us the way forward had become the way backward. It is a skill: knowing when to go.

Part III

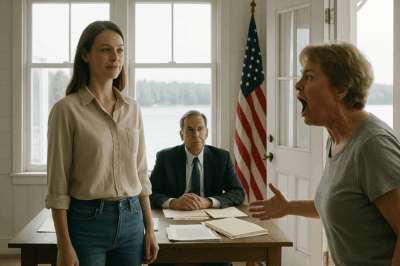

It ended where such stories always end when they decide to end properly: not in blood, not in court, but in a room with a table and three chairs, in a country that prides itself on the shape of its laws even when it ignores their spirit. The deputy director invited me. I accepted because sometimes you must look a man in the eyes so he knows that not everything will be handled by messengers.

He was older. So was I. He poured coffee I would not drink and made a joke he did not expect me to laugh at. The room had the unmemorable carpet all important rooms have. A third chair waited. It did not remain empty.

Julian entered. He looked like a man who had broken and then been reassembled by a mechanic with more compassion than time. He sat without waiting to be told. He did not look at me. That was wise. He looked at the table as if tables could forgive.

“You asked to see him,” the deputy said. “I consider that a mistake I am willing to make.”

“Thank you,” I said.

Julian spoke first, which surprised me in a way that the night’s first siren never does. “They want me to testify,” he said. “Not about her. About her father. About men who aren’t even alive. They want to feed their ghosts with mine.”

“What did you say?” I asked.

“I said yes,” he said. “Not for them. For me.”

The deputy watched, curious as a scientist who has placed two elements together and wonders whether they will burn or merely smoke.

“I am sorry,” Julian said, the words sandpapered by late use. “I was a bad father.”

“You were,” I said. I do not lie to men who tell me the truth. “What will you be now?”

“Better,” he said, which was ridiculous and perfect.

“You will not see him,” I said. “Not yet. Not until better is a building you can invite him into without fear of it collapsing.”

He flinched, then nodded, then breathed. “Tell him I am learning,” he said.

“I will,” I said, because I would.

The deputy cleared his throat. “There is a matter of your… travels,” he said, addressing me as one addresses a weather system. “A long-term vanishing is expensive.”

“It is paid for,” I said.

“By who?”

“By a man who owes a child,” I said.

He held my gaze and then, for the second time in all the years I have known him, looked away first. “Very well,” he said. “Do not mistake this for consent.”

“I never have,” I said. “I take what I need.”

He stood, which in that room meant the meeting had sewn itself shut. “Ghost,” he said—quietly, almost affectionately. “I hope he never learns your name.”

“He won’t,” I said. “He will learn his.”

I left. Outside, the air performed its ordinary miracle of being breathable. On the sidewalk, a boy about Finn’s age tried to juggle three apples and dropped two. He laughed, picked them up, and tried again. I watched him until he learned the trick of it: the tiny, private adjustment one makes in the elbow when one decides to keep trying.

We returned to our latest borrowed life. Finn had made friends with a girl who collected bottle caps and a boy who believed you could fix anything if you had tape and hope. He had written a poem at school that the teacher had pinned to a board and titled “Migration.” It read: We go because we’re going. We stay because we stop. He brought it home and asked me to tape it to the wall. I did. I put it above the kettle, to remind me that water boils at the same temperature everywhere, but what you make with it depends on where you stand.

On a night when the moon pretended to be a coin I might be able to spend, Finn asked, “Are we done?”

“With running?” I asked.

“With missions,” he said.

I considered the line from where we were to where we had to be. I considered the men who would still try to make him a story they could use. I considered the weight of his hand in mine and the ways I had begun to age faster when I sat still too long.

“We are done letting other people write them,” I said. “From now on, we will choose.”

“And what do we choose now?”

“Now,” I said, “we choose breakfast. Tomorrow we choose school. Next week we choose a hike that will make us both sore. After that we choose a museum, and you will be bored until you are not. We choose small missions until they add up to a life.”

He smiled, sleepy and sovereign. “Okay,” he said. “I like that mission.”

“Me too,” I said, and the truth of it surprised me into loving it more.

Months passed, which is to say the clocks kept doing what they always do: demanding attention and being ignored. We stayed in one place long enough that the grocer learned our names and the stray cat began to consider us furniture. I bought a small shop with a window just broad enough to make passersby believe we had more inventory than we did. I sold typewriters to people who pretended they didn’t own laptops. I repaired radios for men who missed static. I told no stories I didn’t have to.

Finn grew into a boy who could fix a hinge and decline an invitation without being cruel. He learned to make an omelet that held together the way decisions do when made carefully. He learned to say no to a teacher who wanted him to join a team he did not like and yes to a friend who needed money without making him feel smaller. He learned the art of not needing the last word. He learned also to win.

In the spring, a package arrived with no return address, which is always a challenge. Inside, wrapped in paper that looked as if it had been folded by someone who respects corners, lay a single photograph. It was of a grave I recognized—the one I had not dared visit again—and a bouquet of lilies that looked exactly like apology. Tucked into the frame: a note in a hand I had once kissed. I am learning too, it read. I let the paper hold my tears, because paper is good at that.

We celebrated Finn’s next birthday in a garden that did not belong to us but did not mind our presence. He blew out candles and could not think of a wish because, he said, he was tired of wanting. I told him to wish for the persistence to keep loving what he already had. He did. The wind decided not to interfere.

It was not a fairy tale. Some nights I woke to the sound of my own heart knocking and it was nothing. Some days the mailman’s shadow made me itch. The Agency did not forget us; it simply learned to pretend we did not interest it. The world remained as it always is: a roomful of knives and spoons, a street where kindness trips over cruelty and gets back up. But we lived there. On purpose.

On a Sunday—because Sundays are for endings and beginnings—we returned to the jungle. This time we came as tourists who refuse to be tourists. We hired a guide who laughed at our jokes and respected our silence. We stood under a canopy that adjusted its light like a cathedral built by weather. Frogs spoke. They made their bright announcements with no shame. Finn listened with his whole face and then said, in the tone of a boy who does not yet know how wise he is, “They are not warning us. They are introducing themselves.”

“Yes,” I said. “Exactly.”

We did not touch them. We let them be beautiful and dangerous in the way of all honest things. We walked back to the trailhead and bought a soda that was too sweet and we drank it anyway and we did not die. I drove us back to our little house and made eggs, and Finn read to me from a book about explorers who got lost and then found themselves by admitting they were lost, and outside the window a neighbor hammered something into place that had not been in place before.

That night, he slept the sleep of boys who had counted birds. I sat at the table with the map and drew a line from where we were to where we had to be and then, for the first time in a long time, I put the pencil down. The line could wait. The mission could be to stay.

I went to his door and watched him. He had the same expression he had when he was a fevered bundle on my stoop—peaceful, trusting, infuriatingly breakable. I closed the door softly and stood in the hallway and let the house teach me its sounds. The refrigerator’s argument. The tick of the clock. The distant bravery of a motorcycle. My heart, rehearsing.

I do not know what the Agency will do next year. I do not know whether Julian will become a man his son can meet without anger sitting down at the table with them. I do not know whether the world will remember to be kind long enough for us to make the next set of small, good choices.

I know this: if they come, I will be ready. Not because I have sharpened blades or studied blueprints—though I have done both—but because I have learned the shape of the one thing that beats an empire every time: a life lived on purpose in the light, with the doors locked and the kettle on, with a boy who will grow into a man who carries his own map.

My name is Cyrus to the neighbors and Ghost to the corridors that prefer whispers. Once I tidied the aftermath of men’s greed. Now I tend a boy’s future. It is the cleaner work. It is the harder work. It is the last work I will do.

Before I sleep, I walk to the window. The moon has not asked permission to rise. It never does. I raise my hand to it, palm open, as if catching something invisible and rare. It is warm, or perhaps that is only my blood remembering.

“It’s cleanup time,” I say to the empty room, and the words mean something different now. Not a warehouse. Not a cartel. Not a file that will be locked in a cabinet until it grows yellow and proud. They mean breakfast. They mean homework. They mean telling the truth to a boy and trusting him to carry it farther than I could.

In the morning, we will go to the market and buy oranges and a loaf of bread that forgives. We will sit at the table and talk about maps. We will choose small missions and complete them without applause. And if someone knocks at the door, I will open it with my softest hands and my hardest eyes, and I will say, very politely, that we are not taking recruits today.

The line from where we are to where we must be is short. It fits inside this house. It fits inside his chest. It fits inside mine. I draw it every night now, invisible and exact. And every morning, we walk it—not as ghosts, but as what ghosts envy: the living.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside

HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside Part…

CH2. “May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record

May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record Part I The sun…

CH2. Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL

Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL Part…

CH2. “You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader

“You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader Part I The…

CH2. “Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp

“Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp Part I — The…

CH2. Four Recruits Surrounded Her in the Mess Hall — 45 Seconds Later, They Realized She Was a Navy SEAL.

Four Recruits Surrounded Her in the Mess Hall — 45 Seconds Later, They Realized She Was a Navy SEAL …

End of content

No more pages to load