Anna Hart walked into her grandfather’s will reading expecting closure. Instead, she heard a “new document” that erased her name and handed everything to her father and sister. The problem? It was signed on a day her grandfather couldn’t even hold a pen.

Part I — The Seat They Saved for Me

The text came at 7:12 a.m., three hours before the will reading.

Don’t get your hopes up about the will.

It was from my aunt, which meant it was both warning and apology. I thumbed back, Thanks for the heads-up, then deleted the thread before I could decide if answering made me complicit in my own erasure.

At Lell & Bonner, the conference room smelled like lemon polish and old paper. Leather chairs ringed a long walnut table, its surface so glossy that every fluorescent tube overhead doubled itself and made the room seem brighter and colder than it was. My father sat near the head of the table, leaning into my sister the way a man leans toward a mirror he likes—hand on her shoulder, cheek tipped to catch her profile. She was perfect in that catalog way she cultivates: smooth hair, soft blouse, mascara that keeps its promises.

They didn’t offer me a seat next to them. That was fine. The surprise of losing something comes duller if you don’t have to stand up to let someone else sit down.

I set my bag on the chair at the far end and told myself again, calmly, that grief and strategy can share a table if you teach them how. In the outer pocket of my bag, a black accordion file with a plastic handle sagged like a stubborn suitcase. Inside: receipts, emails, parking stubs, chart notes, a notarized affidavit in which I had written nothing that couldn’t testify. In the inner pocket, a photo of me and my grandfather on the lake house dock five summers ago, both of us in borrowed hats, his hand splayed across mine like a promise.

When people ask me about “family,” my mind does not go to Christmas tables or casual group texts. It goes to my grandfather’s kitchen at 2 a.m., the night my start-up cratered and I showed up with raccoon eyes and a voice full of splinters.

“Failure is tuition,” he’d said, pouring tea as if anything could be made easier with boiling water and leaves. “You paid the fee. Now use the lesson.”

When my marriage collapsed and I called him from a sidewalk with rain pooling in my shoes, he said, “You’re not broken, Anna. You’re free to choose again.”

My father never used verbs that way. His favorites are owes and should. At dinners, when ideas floated into the air like someone turning on a ceiling fan to move the heat, he would wave his hand at mine and say, “Let someone capable handle it.” My sister learned to be the someone. All she had to do to earn the credit was show up at the end and add napkins.

Later, when his power bill went overdue or there was a form he didn’t want to stand in line to submit, the group thread would ping with: Anna can handle it. It was never phrased as a request. I learned to bring groceries without asking. To cover late utilities “just this once.” When I balked, my sister’s voice tilted sweet. “Better let someone reliable handle it,” she would say, as if I had chosen unreliability out of spite, as if grocery money grew in my pockets like lint.

My grandfather would shake his head when this dynamic played out in front of him. “Don’t let them write you out of your own story,” he’d whisper when we cleared plates. But every time my father dismissed me mid-sentence and my sister took the credit without making eye contact, another brick landed on my chest.

The thing about being crushed is you eventually get low enough to find footing.

I stopped arguing at the table and started keeping records.

I printed every email my grandfather sent that referenced the lake house and slid them into plastic sleeves—three copies of the one that mattered most: The lake house will be Anna’s. I kept one set at home, one at work, one offsite in a PO box near the bus stop that my family didn’t know existed because nothing goes missing faster than mail when the person with the mailbox key pretends not to recognize your name.

I scanned his letters and saved the PDFs in a folder named with dates instead of feelings. When I visited him in the rehab wing after his small stroke, I bought two coffees in the lobby, asked his nurse for the exact names of his meds, and made a note of the tremor in his right hand: frequency, amplitude, time of day. I requested the occupational therapist’s letter about his fine motor control and filed it under MEDICAL: CAPACITY. After March, his grip was inconsistent, the note read. She described tremors, fatigue, and sedation on imaging days.

At legal aid, a volunteer attorney named Rosa read my folder like a doctor palpating a wound. “Preserve metadata,” she said. “Download originals. Don’t forward. If you keep a timeline, lead with dates and locations. Adjectives lose credibility. Facts don’t.”

I asked the two neighbors who brought casseroles to the porch to sign witness statements about the days they saw my car in the driveway at dawn. They attached time-stamped phone photos where you could see the porch light on and my grandfather’s silhouette in a window. I studied his signature on birthday cards—where the loops drooped after the second word, where the ink thinned on the tail of his y.

I did not accuse him of anything—not in my head, not on paper. I practiced noticing. Truth doesn’t need volume. It needs a clear path.

Preparation felt like oxygen after months of being told I must have forgotten to breathe.

Part II — The Codicil

The attorney cleared his throat. “For the record,” he said, pressing the red button on a pocket recorder, “we’ll first read the original will, executed June 3, 20—, followed by a codicil, executed April 12 of this year.”

My father’s posture straightened as if bolstered by the word executed. My sister’s hands folded themselves into a prayer she didn’t believe.

The original will was what I knew it would be: a bequest to the county library; a scholarship fund with my grandfather’s name, because he believed future should be funded; specific items to specific friends (“to Juan, my ratty wool sweater he always mocked but borrowed when November surprised him”). And then the line that had floated me some nights like a life preserver: “The Lake House, with contents and riparian rights, shall pass to my granddaughter, Anna Hart.”

If grief had fingers, I felt them ease off my throat. My aunt squeezed my shoulder once, her nail digging in like a safety pin, then let go.

“Now the codicil,” the attorney said, voice level as a plane.

Paper rustled. My father’s mouth found a smile it had rehearsed. My sister did not look at me; she held her happiness forward like a tray.

The codicil revoked the lake house clause and left “the residuary of my estate” jointly to my father and my sister. The language was bland; the effect wasn’t. The room did that thing where everyone politely waits to see who will applaud first and then pretends they are not relieved they didn’t have to lead.

I didn’t clap. I looked at the date again. April 12.

On April 12, the chart note from RN Patel read: “Sedated for imaging at 14:10. Motor coordination compromised. Tremor notable.” On April 12, I had been in his room at 6:40 p.m. holding a paper cup so he wouldn’t spill water on his gown. On April 12, my sister had posted a photo of her latte on Instagram at 1:58 p.m. with the caption, “Self-care is key.” In the blurred background you could make out a window that belonged to a café across town from the rehab facility.

“Witness signatures on page three,” the attorney said, sliding copies across the table like menus. Two names sat there—neat, unfamiliar. No addresses. No phone numbers. No notary stamp. The codicil didn’t list the hour of execution.

My father leaned back in his chair and whispered, “Best for the family, finally.” To anyone listening, he sounded like a man magnanimous in victory. To me, he sounded like someone expecting me to fold. He has always confused my silence with agreement.

I wrote two lines in my notebook: Apr 12 — capacity?; Witnesses: contact info? Notary log?

“Any questions before we conclude?” the attorney asked, professional neutral.

“No need,” my father said, answering the room with the confidence of a man who has never been asked to show his work. “We’re satisfied.”

“Just one,” I said. “Can you confirm the time of execution?”

The attorney flipped pages, scanned, frowned. “The codicil lists the date only,” he said. “No hour.”

“Thank you,” I said, and slid the copy into my file behind the doctor’s letter. A missing hour is still a place on a map. You can stand there and measure the distance to everything else.

Applause patted the table again, tinny and eager. It passed over me the way elevator music passes over the lobby: sound without consequence.

I asked for a meeting in the morning—“Paper only,” I said on the phone. “No toasts.”

Part III — The Contest

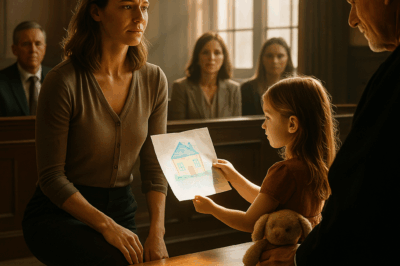

We sat around the same table, but this time my aunt took a chair directly behind me and planted both feet like ballast. The attorney placed the originals between us like an altar.

“I’ll be brief,” I said, because I had learned brevity inhabits authority. “Three points: capacity, execution, and intent.”

I slid the original will to the left, the codicil to the right, and my timeline down the center. Dates walked up their rungs like they had when I wrote them—clinic appointments in blue ink, coffee purchases in black, chart notes in a careful nurse hand, my porch-light photos glued to an 8½×11 sheet because the clerk in me still likes tape.

“Capacity,” I said, tapping the doctor’s letter. “After March, his grip was inconsistent. April 12—sedated at 14:10. Motor coordination compromised. Inconsistent tremor. Fine motor control impaired.” I set down the March birthday card where his soft loops faded on the tail of the y in “happy.”

“Execution,” I continued, sliding the codicil forward with one finger. “No hour listed. No notary stamp. Witnesses with no addresses or phone numbers. Both signatures appear consistent with each other, not with a tremoring hand.”

My father inhaled through his nose the way he does when he’s about to say something condescending only he thinks sounds wise. “He changed his mind,” he said. “He realized Harmony matters. He didn’t want conflict.”

“Harmony would not require strangers to witness,” I said. “Harmony wouldn’t mind a notary stamp. Harmony would tell the truth to paper and to people. Also—” I slid across two printed emails with full headers and preserved metadata “—January and March: ‘The lake house will be Anna’s. Keep the taxes current. She knows the caretaker.’”

My sister’s chin lifted. “You never finish anything,” she said, the bad penny of a line we had grown up spending on each other.

“I’m finishing this,” I said. “In writing.”

The attorney cleared his throat. “Ms. Hart,” he said to me, voice cautious but—if I am honest—respectful. “My duty is to the estate, not to any one heir. Given the discrepancies and the question of capacity, I will suspend distribution and petition the court for instructions. We will secure the originals in our vault. In the meantime, please provide your written objections with exhibits.”

He slid a legal pad toward me. “List what you want copied.”

I wrote without adjective: originals; notary journal April 12; contact info for both witnesses; email headers with time stamps; chain-of-custody for codicil; any drafts in Mr. Lell’s file; metadata preserved; clerk receipts; medical chart notes; OT evaluation.

My father tried to put his hand on the table in a gesture of control that had worked for him since 1989. “Handle this privately,” he said. “No need to drag our family through—”

“Privately is how records disappear,” I said, standing so quickly the chair legs squealed on tile. “Publicly is how records stand.”

Part IV — The Hour That Didn’t Exist

Probate Court doesn’t look like television. There are no galleries craning to hear, no gasps, no music swell. There is a judge with a calendar that already hates your drama, a clerk who’s seen everything, a room that smells like toner and obligation. The file number—people boiled into digits—lives on a blue folder tab. The record consists of paper lined up like a neat argument and the hour stamped at the top of the order when a life changes without the sky noticing.

We filed the petition to contest the codicil within the week. The court ordered the attorney to produce the notary journal, to explain why the codicil lacked a time of execution and how two witnesses with no contact information had signed without addresses. It ordered the rehab facility to produce the medical record for April 12. It permitted a handwriting expert to compare known samples to the codicil signature. It appointed a guardian ad litem to advocate for the estate separate from any of us. It did what courts do when they are reminded they are made of process, not feelings.

The notary journal, when it finally arrived, was a photocopy of a page with neat entries for April 11 and April 13 and—curiously—nothing for April 12. The notary’s log had a gap where my grandfather’s signature should have been. When asked to explain, he said he “must have forgotten” to record. The handwriting expert’s report compared the codicil signature to the birthday card and other known samples and used phrases like “inconsistent stroke pattern,” “uncharacteristic line quality,” and “possible simulation.” The rehab facility produced Ms. Patel’s note with its precise minute: 14:10. Sedated for imaging. Motor coordination compromised.

The court’s order, when it came, was one and a half pages long, stamped with the quiet authority of a tired institution doing its job.

FINDINGS: The court finds the proffered codicil invalid for failure of due execution, lack of capacity at time of purported execution, and failure of proof regarding witness attestation. The court reinstates the June 3 will in full force and effect. Distribution shall proceed accordingly.

I read it twice and then a third time because sometimes disbelief is just your brain asking for confirmation without admitting it. Then I called the caretaker for the lake house and said, “Hi, Rick, it’s Anna,” and breathed in his shocked laugh like oxygen.

My phone buzzed with messages I’d stopped hearing months ago. My father texted: We can settle this without dragging our name through mud. My sister sent a single line: You didn’t have to take everything.

“I took responsibility,” I wrote back. “You tried to take the truth.”

The attorney emailed PDFs of the order and then mailed certified copies because real wins come with postage. I drove to the lake the next day, the leaves making their loud crunchy noise under the tires the way they always had, announcing you louder than you feel and then forgiving you for it.

The house smelled like dust and cedar and the last argument I’d had with my grandfather about politics. I changed the locks—not to bar and punish, but to draw a clear line, to keep the order inside the walls like heat. I checked the roof. I cleaned the gutters. I bled the radiators in the bedrooms that never warmed up right in January. I set the property taxes to auto-pay with my name and his wish behind it.

On the mantle, his photo looked out at the lake like he was pretending not to be sentimental. I put a framed copy of the court order beside it—not because I plan to worship paper, but because I want to remember what a straight line looks like when you lay it down after a year of being told curves are normal.

Part V — The Name That Held

There were consequences. Not judicial, not yet. I didn’t haul my father and sister into criminal court because I didn’t have evidence that crossed that particular fence. But the notary who’d “forgotten” April 12 found himself required to explain that gap to people with bigger staplers. The two “witnesses” turned out to be friends of my father’s golf partner; when they were subpoenaed, one admitted he had signed blank pages at my father’s request “as a favor.” The ethics board read that sentence twice. The state stared. The state did what it does: moved slowly and then all at once.

I timed my communications with my father and sister to occur by email only. No more group threads. No more “quick question” calls. No more texts arriving at midnight like guilt dressed as duty. Cheers and condolences stopped coming from people who had believed the codicil meant I would go quietly. A funny thing happens when you say, “Put it in writing.” People who want things to disappear find themselves busy.

My aunt came up to the lake one Saturday with a basket that held two sandwiches and a thermos that used to live in her car in 1998. She sat beside me on the dock, shoulders touching, and didn’t say, “I told you so.” Instead, she watched the dragonflies skim the surface of the water and said, “Your grandfather would be insufferable right now in the best way.”

“He’d be making pancakes for ten,” I said. “He’d invite the mail carrier to the table. He’d ask the electrician about her kids and then leave cash where she’d find it even though the bill was already paid.”

She nodded. “He left it with you for a reason.”

I hired a maintenance company to service the well pump and had Rick show me how to flush the sediment filter. I met with a local lawyer to set up the scholarship in my grandfather’s name. I took a call from the head librarian who cried, hiccuped, and then declared she already had a plaque placement in mind that wasn’t tacky.

On the first frozen morning, I stepped onto the dock in boots and watched the steam roll off the lake like breath. Grief sat beside me the way an old dog sits—heavy, warm, content to watch. It wasn’t gone. It had just agreed to be quiet sometimes.

I didn’t call my father to tell him what the light looked like on the ice. I didn’t send my sister a photo of the new paint in the kitchen. I didn’t ask them to approve, to soften, to validate. I stopped asking altogether.

Two months later, a letter arrived from my grandfather’s college—handwritten, careful: Thank you for funding the scholarship. He would be so proud. I unfolded the second sheet and smiled at the name they’d given it: The Arthur Hart “Failure Is Tuition” Award. I could hear his laugh through the lines like static, that full-body chuckle that rattled glasses and made waiters stop to smile.

I pinned the letter under a magnet in the lake house kitchen. Each time I reached for the coffee filter, I read the words again. They didn’t grow dull. They sharpened.

People still ask me about “family.” I tell them the truth: sometimes family is the people who try to write you out of your own story. Sometimes it is the one who taught you to pick up a pen and say, calmly, with evidence, “No.” Sometimes it’s a clerk who stamps an order on a Tuesday and hands you certified copies because she understands that paper protects the quiet people.

If you’re keeping score, here is the tally: my father and sister lost the lake house and learned that people who sign blank pages take oaths they never meant to take. The will stood the way straight beams stand when you stop pretending curves are load-bearing. My name on the deed is not a trophy. It is a task. I change the filters. I shovel the steps. I set the taxes to autopay, not because anyone is watching, but because he asked me to be the person who keeps the heat in.

On the first spring day when the ice finally gave up its grip and the water went black and then blue again, I took the canoe out and drifted to the middle of the lake. The house looked small from there, the way burdens do when you carry them long enough to build muscle. I thought of the codicil signed on a day when his hand couldn’t hold a pen and felt the anger rise again, then pass through, then fall away. What remained was the dock, the roof, the water, the scholarship, the librarian who now had a plaque that didn’t embarrass her wall.

“Don’t let them write you out of your own story,” he’d told me.

I didn’t. I wrote it down. I put it in a folder. I handed it to a judge. And then—this is the important part—I went home and made coffee.

On the mantle, his photo sits next to the court order in a simple frame that isn’t for gloating but for remembering the route. If the day ever comes when someone says again, “Better let someone capable handle it,” I will point at the papers and say, “I did.” Then I will hand them a sandwich, because winning doesn’t mean I stopped learning from the person who fed everyone who paused within range of his stove.

The ending isn’t applause. It’s maintenance. It’s a key that fits. It’s a name that holds because the truth does.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. “You’ll Watch My Kids on the $5,000 Trip You Paid For,” She Smirked — I Let Her Finish Talking

“You’ll Watch My Kids on the $5,000 Trip You Paid For,” She Smirked — I Let Her Finish Talking …

CH2. HOA Karen Took Me to Court… But the Judge Had Other Plans

HOA Karen Took Me to Court… But the Judge Had Other Plans Part I — Letters on the Door…

CH2. My Parents Sued To Evict Me So My Sister Could “Own Her First House.” Until My 7-Year-Old Daughter…

When architect and single mom Clara Morgan built the carriage house behind her parents’ home, she thought she was rebuilding…

CH2. My Sister’s Revenge Almost Cost My Son’s Life. Parents Said It Was Just A Game But Then…

My Sister’s Revenge Almost Cost My Son’s Life. Parents Said It Was Just A Game But Then… Part I…

CH2. My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.”

My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.” My Sister Added A Thumbs-Up Emoji. I…

CH2. My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell Apart

My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell…

End of content

No more pages to load