My Dad Mocked My Worth at Thanksgiving — Then Choked When He Saw Me on CNN Beside the President

Part I — The Handshake and the Fork

The last thing anyone heard before the room went silent was my father’s punchline.

“She’s the mistake I wish I hadn’t made,” Dad told the cousins, carving another long slice of turkey like he was shaping the world with a knife. The table laughed on cue—some out of habit, some out of fear, some because they had always laughed at the jokes that cost nothing to the teller and everything to the subject.

I had learned long ago that silence can be armor if you wear it right. I buttered a roll to the edges.

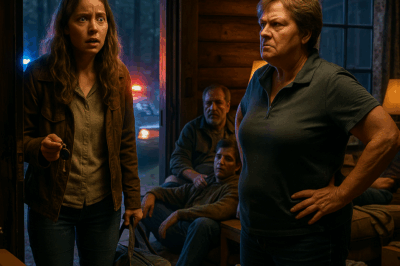

Then the television in the other room, left on to babysit the men when conversation failed, cut from football to the White House feed. CNN’s banner slid into view like a curtain, and the anchor’s voice, cool and professional, said into our dining room, “Live from the East Room—today the President honored a bipartisan panel for its work advising on veteran family reintegration.”

A camera tracked down a line of honorees.

“Wait,” my cousin Josie whispered, her fork lowering. “Is that—”

Another cousin, voice thin, “Oh my God—that’s our President. And… Emily?”

The camera found me—black suit, small U.S. flag pin, something steady in my shoulders I keep there for other people. The President took my hand and said something close to my ear. I nodded, the way you nod when you receive praise on behalf of people who can’t be there to hear it.

My father’s fork hovered halfway between platter and plate. He coughed hard enough to blanch at the face, eyes glued to the screen as if sheer disbelief could edit live television.

The anchor obliged my biography without flourish. “Colonel Emily Carter, recognized for advisory work with veterans’ families and her leadership in building the Transition Standards Toolkit adopted by half the VA regions this year.”

Football went mute. Even the chandelier seemed to listen.

I breathed in—steady in, steady out. The old instinct that had scratched at my ribs all my life—that urge to shrink to make the joke feel bigger—came sniffing for me and found no purchase. It died there.

“Pass the rolls?” I said to Aunt Linda, who instinctively handed them as if returning fire with bread.

Dad scraped his chair back and stood, raised his glass too high. “Folks, I was just having a little fun,” he said. The refuge of a joke, that sterile room where the puncher is the doctor and the bleeding is your fault for not taking a ribbing.

I kept my eyes on the cranberry sauce as if it were horizon. “I’d like to finish my plate.”

The sentence landed the room back in its chairs. The television flickered away to weather; the President retreated into a box above the score. Knives resumed their harmless work.

Across from me, my son Mark caught my eye. Eighteen months married, hotter temper than he admits, he stared at me the way boys do when they want orders and permission at the same time. I gave him the smallest nod: we’re fine. He set his jaw and put his napkin back in his lap; the room cooled by two degrees as the cousins followed the shortest man’s lead.

“You knew,” Aunt Linda breathed, forgetting Mom has been dead ten years and that I stood two chairs away. “You planned it.”

“I do a lot of planning,” I said. “Quiet professionalism. Do the hard thing. Speak softly. Get your people home.”

Dad sat down with more force than necessary and pretended to be interested in the sweet potatoes. He cut them as if they’d harmed him.

He lasted until the pie. When the cousins drifted toward the living room and the commentators started praising a backup quarterback like he’d invented bravery, Dad wandered into the kitchen, leaned against the door frame, and flipped the switch on a face I know too well.

“You made us look foolish,” he said in a voice pitched for control.

I set a plate upright in the drying rack, shut off the water, and faced him. “I didn’t make anything. I stood in a room where I was asked to stand.”

“You could have warned me about—about your life,” he said.

“Or about your joke,” I said gently. The simple verb is the sharpest knife. He flinched—the way men do when a mirror finally arrives and turns out not to be decorative.

From the doorway, Mark offered a lifeline to a man drowning in his own mouth. “Grandpa,” he said. “Game’s back.”

Dad retreated into the safer current. He muttered something about officiating and called an audible on his own behavior by leaving the kitchen.

I turned the water back on. There is holiness in the worship of clean dishes. It gives your hands something to do when the heart is excavating a new room.

Part II — Standards, Not Speeches

The morning after Thanksgiving smelled like coffee and the tired breath of store-bought flowers. Vases lined my counter like a small-town parade float—tilting a little, still trying to be beautiful. My phone pulsed with texts that used the same two words in aching alternation: proud of you; sorry about your dad. I slid the phone face down. Truth didn’t need replies. It needed room to stand.

I grew up on a two-lane outside Chillicothe, Ohio, where men measure distance in minutes and cement in bags. Dad ran a plumbing and HVAC outfit from a cinderblock shop behind the house. He was good with systems; we wore furnaces like long winters. He was rough with people, especially the ones who shared his last name. If a pipe leaked, he tightened it. If a child hurt, he mocked it. That was the method.

Sundays were polished pews under a stained-glass window of wheat and water. After church, Dad would shake the preacher’s hand and declare the sermon “tight work,” the way he praised a clean solder joint. In the parking lot, he’d squeeze my upper arm like checking produce. “We’re laying off donuts this week, right?” he’d say. The men laughed. The women looked away. Humiliation loves a parking lot.

Mom made casseroles and apologies like a woman paid in leftovers. She loved me enough to salve, never enough to stand in front of the blows. When she died after a quiet war with her heart, the house lost its soft; the jokes got longer. I learned to become useful. I swept the shop floor, sorted fittings, balanced invoices on a yellow legal pad. Dad relied on my neatness while ridiculing my body. “You’d be perfect if you came with a shutoff valve,” he told a supplier, delighted with his wit. I learned pretending is a skill. It buys time until courage grows.

A guidance counselor slid an Army brochure across her desk my senior year. “You’re organized and stubborn,” she said. “Those go far.”

Organized and stubborn: the first words to land as compliments, not conditions. At dinner I said, “Army.” Dad looked up long enough to do a drum solo with his fork. “You’ll fold the first time someone yells.” I signed my contract on my lunch break and hid the carbon copy in my geometry binder.

Basic training was the first time in my life where the only thing anyone measured was my performance. You rise at 0400. You answer to a last name without flinching. You square corners on a bed that taught you how demanding a rectangle can be. You learn how fear fits in your fist. A drill sergeant yells—yes—and you discover that not all shouting is cruelty. Some of it is math.

Promotions arrived the way dawn does—gradual, then obvious. Private to specialist. Specialist to sergeant. Captain, major, lieutenant colonel, colonel. Not because I walked around demanding attention. Because I made the map outside match the map inside. Iraq taught heat. Afghanistan taught mountains. Washington taught that policy is a quieter weapon, and if you place it right it saves people you’ll never meet. I wrote a toolkit for commanders dealing with families in the hardest season they’ll know. We piloted it quietly with four bases. We didn’t advertise until metrics made it safe to ask for applause.

The President’s office called a week before Thanksgiving. “We’d like to honor the team who built the Veterans Family Transition Standards,” the woman said, voice smooth as glass. “It would be an honor,” I answered. I bought a jacket at a thrift store for forty dollars and had it tailored for two hundred. Men think nothing of spending three hundred dollars to be taken seriously. Women record the receipt.

I didn’t tell Dad. I didn’t tell anyone. Not because I wanted the ambush at dinner. Because in my family a uniform becomes a prop and ceremony a cudgel. I didn’t want to hand them either.

The night after the handshake, I drove down to the shop. The roll-up door was half open. The radio played a station that doesn’t make anyone angry. Oil and old cardboard made the air thick. Dad sat hunched over the ledger with a pencil, forcing numbers to behave.

“We should talk,” I said.

“We talked enough last night,” he said to the column of expenditures, engaging in the national pastime of dodging accountability with accountancy.

“No,” I said. “You talked. Then other people did. I’d like to speak now.”

He set the pencil down with exaggerated care—the kind of care that bruises because it pretends to be gentleness—and didn’t meet my eyes.

“It was a joke,” he said finally.

“Jokes are funny to the person who hears them,” I said, “not just the person who tells them.”

He huffed, an air leak in a system he built to run on disrespect. “People laughed.”

“And then they didn’t,” I said. “That’s the part to remember.”

He picked up the pencil again, put it down again, performed competence while something in him fumbled behind the wall. “You never said what you do,” he muttered.

“You never asked,” I said. Not a punch. A measurement. He had filled in the blank with a story he preferred. “Military is just a job,” he offered, as if that narrowed the field to his advantage.

“It is,” I said. “So is fatherhood.”

He rubbed his jaw as if the sentence had left a mark. Outside, a pickup drove by with a flag in the bed that refused to hold still. Inside, the radio found a commercial about winterizing pipes. I decided to give him a ladder.

“You stop buying power with my dignity in public and private,” I said. “I stop bringing myself into rooms where I am not respected. That includes holidays. It includes Mark. I won’t let him absorb a master class in cruelty from the man who taught me to pretend it was normal.”

“You’d keep my grandson from me?” He said it like a challenge, like a man daring a pipe to leak deeper into winter so he can charge more to fix it.

“I’d keep your behavior from him,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

He stared at his hands like he didn’t recognize the tools they were. The fan rattled in the corner every fifth rotation. He cleared his throat. “I got hard,” he said, not lifting his eyes. It came out not as a boast this time but as a diagnosis.

“I got clear,” I said.

He nodded—a single, stubborn clunk of the head, as if we were agreeing on the length of a board we both had to cut. Progress is sometimes nothing more than two people measuring the same piece of wood with the same tape.

Part III — The Town Learns, The Family Practices

Two days later, the town’s weekly taped the memorial photo to the inside of its window: Scouts in sashes, a flag flared by wind, our new plaque under the nylon that had just been pulled. The editor added a single sentence in no one’s particular font: “Tell the truth when it would be easier not to.” C. Carter. He gave me an initial. He didn’t need more.

At the Veterans Memorial on Saturday, Pastor Jean kept the benediction short and someone’s kid held the scissors wrong and still managed to cut the ribbon, and that’s how you know mercy moves faster than perfection. I said fifty-two seconds’ worth about standards and stewardship and the work of bringing people home. Dad stood to my left without making my presence about him. When people asked him afterward if he was proud, he said, “She runs things bigger than this grill,” at the cookout the next day. It wasn’t poetry. It didn’t need to be. Standards, not speeches.

Staff Sergeant Miller found me at the memorial with two men who wore their civvies like loaned comfort. They thanked me for a night in Khost Province (he spelled it for Dad without rolling his eyes), for walking truck to truck when the radio went dark, for teaching them that fear is weather and standards are climate. Dad shook their hands, husk words. For the first time in memory, he talked about me in a room without belittling me to buy applause. He stood beside me as if his shadow belonged there.

On Sunday, at my brother’s backyard cookout, the usual circle formed near the grill to worship at the altar of meat. Dad passed me the tongs and didn’t pretend to have invented fire. When cousin Tyler tried out a joke because habit is a heroin, Dad interrupted with a sentence so soft it startled the men: “We’re eating. Try being decent with your mouth full.”

He didn’t look at me when he said it. He didn’t need to. The sentence did its work in the spaces jokes usually bruise.

Neighbors told me stories some version of “I saw what happened on TV” and “We’ve always been proud” and “I’m sorry.” I accepted the pride. I let the apologies evaporate without sticking to me. You can’t build anything on someone else’s regret unless you like to live on shifting ground.

When the get-together wound down into Tupperware negotiations and the closing arguments of children bargaining for one more cookie, Dad walked to my car with a brown paper sack.

“Tomatoes,” he said, as if contrition can be sliced and salted. “Guy at the shop gave me too many.”

“They’ll spot the counter,” I said, still speaking the language we share.

He held up a folded paper towel. “Brought insurance.”

We stood by the open trunk and ate a tomato in quarters, salt from his pocket making sun taste like summer. “About Saturday,” he began, then stopped himself. “I’ve said I’m sorry,” he tried again. “I’m going to keep saying it, but less. And do it more.”

“Good order,” I said.

He nodded toward church. “I’ll try not to park where I can block anyone in.”

“Progress,” I said.

He saluted with two fingers—stolen from the men in seed caps who stole it from county deputies who stole it from someone’s grandpa. I let him. We aren’t an army. We’re a family learning a new standing order.

Part IV — The Call, the Letter, the Standard

On Monday morning, I opened the door to find an envelope on my doormat—white, hand-addressed, no return. Inside: a photo printed on cheap paper of four dusty faces in Khost light, myself among them, eyes narrowed against sun, my face younger than I remember. A letter in a steady hand: “Ma’am, we saw the footage. We keep our wobble straightening where you said it would. With respect, we’ve got your six.”

That’s the thing about jokes—they don’t last long enough to build anything. Standards outlive the teller.

Dad stopped by that afternoon with a sandwich in a brown paper sack. He knocked and waited instead of walking in like a man defaulting to ownership.

“I’ll leave it on the porch if you’d rather,” he said. “Turkey on wheat. Mustard.”

“Thank you,” I said, taking it. “I’ll return the jar.”

He nodded at the little sign I keep over my doorway—a scrap of wood from the old shop burned with three words: “Steady is brave.”

“That a sermon?” he asked.

“It’s a standard,” I said.

He looked at me the way men look at a measuring tape stretched across a board and realize the inches don’t care who’s holding them. “Standards,” he said slowly, trying the weight of the word in his own mouth. “We can do standards.”

“We have to keep doing them,” I said. “Even when no one’s filming.”

That night, I sat at my kitchen table and wrote a note. “Dad—Thank you for the sandwich. I’m willing to keep practicing as long as you are. Terms are on the back. No public jokes at anyone’s expense. No private cruelty about my body or my work. Ask before telling my story. I’ll answer plainly. I’ll make room for you when you use that room well. —E.”

I slid the note into an envelope and propped it against the tomato jar.

The next morning, I dropped a letter in the blue mailbox on Main addressed to the chaplain. “Quiet professionalism is not silence,” I wrote. “It’s stewardship—of rooms that might otherwise be bought with someone else’s dignity. Thank you for reminding me.”

A teenage usher from church found me at the diner later, hair combed into compliance, tie too tight. “Ma’am,” he said, nervous. “ROTC applications are due. My dad says I should write about wanting to be a hero. I don’t know what that even—”

“Write about carrying heavy things,” I said. “About getting other people home. About telling the truth when it would be easier not to. Hero is a word other people get to use for you if they must. You use standard.”

He nodded like a kid being trusted with a grownman tool.

Dad called that night. “What’s the thing Sunday?” he asked. “At the memorial they said something about volunteers.”

“Cleanup day,” I said. “Leaves and paint. No speeches.”

“I’ll bring a rake,” he said, a man who knows how to make his body useful when words aren’t enough.

I said good night and looked out at the feeder. A sparrow and a jay shared it for six consecutive minutes—longer than last week, longer than all the weeks before. We’re not wildlife managers, but we can learn from them: stand, yield, return. Try again.

On the news, they reran the handshake. Someone will always be discovering that clip anew; someone will always be choking on their turkey in a living room that needs a new climate.

The world will keep offering me microphones. I will keep offering it standards.

You might be waiting for a catharsis that feels like a slammed door. I have learned to love the quieter victory: a father who opens a screen door slowly so it doesn’t bang; a town that changes the way it claps; a teenager who prints “organized and stubborn” onto a college essay; an Army chaplain who writes “stewardship” and underlines it twice; a Thanksgiving table where, at the first sound of an old kind of joke, a dozen forks pause in mid-air and do not come down.

If you’ve gone this far with me, carry this, too: The greatest revenge is not humiliation. It’s reconciliation on your terms, lived so consistently that it teaches the room to behave. And on the days reconciliation isn’t safe, the revenge is smaller but holy: the room you build where your worth is not negotiated.

The President’s handshake was a moment on television. The real work is this: finish your plate, steward your kettle, write back, return the jar, hold your people, and make sure the jokes that used to buy power now bounce off a house that refuses to turn laughter into currency.

Standards, not speeches. Quiet professionalism. Do the hard thing. Speak softly. Get your people home.

And when the chandelier in your family dining room stops vibrating and the football game comes back on and the room tries to forget, don’t let it. Your steadiness will linger longer than the applause. Your refusal to be the joke will teach everyone at that table the shape and weight of a better climate.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I Used Sign Language to Help a Deaf Homeless Veteran, I Had No Idea a Four-Star General Was Watching

I Used Sign Language to Help a Deaf Homeless Veteran, I Had No Idea a Four-Star General Was Watching …

CH2. Here’s The Card Buy Whatever You Want, There’s $5 Million On It — My Mom Handed My Card To Brother..

Here’s The Card Buy Whatever You Want, There’s $5 Million On It — My Mom Handed My Card To Brother…..

CH2. HOA Karen Called the Cops When I Came Home Early—Her Whole Family Had Taken Over My Cabin!

HOA Karen Called the Cops When I Came Home Early—Her Whole Family Had Taken Over My Cabin! Part 1 —…

CH2. The Captain Said “Stay Out of This” — Then Watched Her End the Fight in One Move.

The Captain Said “Stay Out of This” — Then Watched Her End the Fight in One Move Part I —…

CH2. Mom Woke Me at 3 A.M. Laughing, ‘Pack — You’re the Surprise Guest,’ Then Dropped Me Off at a Shelter

When my mom woke me at 3AM laughing and told me to pack my bags, I thought it was a…

CH2. They Laughed at the Tattoo — Then They Froze When the SEAL Commander Saluted Her

They Laughed at the Tattoo — Then They Froze When the SEAL Commander Saluted Her Part 1: Butterfly, Clipboard,…

End of content

No more pages to load