My BROTHER Was Buried 42 Years Ago… But Last Week I Got A Call At 2AM & He Said “It’s Tommy” & My World Stopped

Part I — The Voice

I buried my brother when I was twenty-three. Tommy was nineteen—brown-eyed, quick-smiled, a kid who could fix a radio with a butter knife and a prayer. On a January night in 1983, a Greyhound bus lost the road on the Coquihalla and slid into white. Seventeen dead, the newspaper said. I stood in a morgue in Hope, British Columbia, under a light that made everything too clear, and told a man with a clipboard that the battered face under the sheet was my brother’s. Then I drove home to tell our mother her youngest boy was gone.

Last Tuesday, my phone rang at two in the morning. Unknown number. Vancouver area code. I almost let it go to voicemail. At sixty-five, you learn that nothing good comes at that hour. But my hand moved before the call could slip away, the same instinct that once had me waking up when Tommy’s childhood nightmares began to shake the bunk.

“David?” The voice on the line was rough, uncertain—not gravel from whiskey or cigarettes, but the confusion of a man whose speech has been mothballed too long. “Is this David?”

I sat up. The room changed shape; the darkness edged with white as if it wanted to redraw itself.

“Who is this?”

Breath filled the space between us: heavy, steady, laboring. “It’s me,” the voice said. “It’s Tommy.”

I dropped the phone. It bounced, thumped, skittered against the nightstand. I had to feel around with both hands on the floor to find it again, like a blind man reaching for a rail.

“This isn’t funny,” I said when I had it to my ear again. “Whoever you are—this is sick. My brother died forty-two years ago.”

“I know,” the voice said. “I know how long it’s been. I just—” he inhaled, ragged, like a swimmer about to go under—“I just figured out who I am. I found something. A newspaper clipping about the bus crash. And there’s a picture of me, but the name under it says Thomas Carr. That’s me, isn’t it? I’m Thomas Carr.”

The room tilted, then steadied. A hundred things I had forgotten to forget woke up at once and sat on the edge of the bed.

“Where are you?”

“I don’t—I don’t really know. A place called the Downtown Eastside. Someone told me that’s what it’s called. I’ve been here a long time. I think I live in a shelter on East Hastings Street. But I don’t remember.” His voice faltered but did not break. “I don’t remember how I got here. I don’t remember anything before about fifteen years ago. Just waking up in a hospital, and they said I’d been found on the street and I didn’t have any ID and I couldn’t tell them my name.”

The mind wants to protect itself. It throws up fences: skeptic, cynic, a dozen reasonable questions that say you are being played. I clung to all of them like a person holding onto the rules when the fire alarm sounds.

“What do you remember?”

“Nothing clear. Feelings.” He searched within himself for words as if they were objects buried in snow. “Sometimes I dream about snow, about being cold, about people screaming. And sometimes I dream about a house with a blue door. And someone used to make pancakes with blueberries. Every Sunday.”

I had to put my hand over my mouth then. Our mother: mixing bowl, radio on the counter, blueberries that stained the batter purple. Tommy always asked for seconds before anyone else had finished firsts. The door—old paint, color of the sky when it’s trying to cheer you up.

“What do you look like?” I asked, and I hated the question as soon as it left me because it was so bald, so desperate.

“Old,” he said, and the sadness there went through me like cold water. “Really old. My face is…weathered. I think that’s the word. I’ve lived rough for a long time. But I found this picture in the newspaper from the accident. Even though it’s forty-two years old, I can see it. I can see myself in that face. We have the same eyes.”

“Tommy had a scar,” I said. “On his left forearm. From when he fell off his bike. Twelve stitches. You cried at the stitches, not the fall.”

There was a pause. The clink of a chair somewhere in the background. “I have a scar on my left forearm,” he said slowly. “It’s old. Really old. I never knew where it came from.”

“Give me your address,” I said. “Right now.”

“I don’t think you should,” he whispered. “I don’t think I’m the person you remember. I don’t…remember being him. I’m just someone who’s been living on the streets for longer than I can recall. I probably smell bad. I probably look scary. I just wanted to call because—because someone should know that maybe I didn’t die. That maybe there was a mistake.”

“Tell me where you are.” I put both feet on the floor and stood half-dressed in a room that didn’t feel like mine. “I’m coming.”

He gave me the name of a shelter and a address on East Hastings. I wrote with a pen that left a groove in the paper, my hand shaking so badly I had to steady it against the nightstand.

“Don’t go anywhere,” I said. “I’m leaving now. I’ll be there by noon.”

“Okay,” he said. “Okay, David. I’ll wait.”

The line clicked. The room refilled with ordinary dark. I stood there for a long minute, stunned by the body’s capacity for stasis and speed. Then I moved.

My wife, Sarah, lifted her head as I buttoned my shirt. “David? What’s wrong?”

“I have to go to Vancouver,” I said. My voice sounded like a recording of someone else saying the sentence I was supposed to say.

“At two in the morning?”

“I have to go.” I kissed her cheek. Her skin was warm, familiar. “I’ll call from the road.”

The highway between Kelowna and Vancouver is a lesson in weather and faith. The mountains step out of the dark slowly, as if not quite sure whether they want to be seen. I drove with the radio off because the world already felt too crowded. The years between nineteen eighty-three and now replayed in ragged loops. The morgue. The sheet. The shape of a nose. The certainty of a man who needed certainty more than he needed to be right.

What if I had been wrong? It is a question with teeth. It ate at me until the sky began to pale.

I reached Vancouver before noon. The Downtown Eastside was exactly what I had heard and worse because hearing and seeing are different countries. Boarded storefronts, bodies moving like shadows, the taste of despair at the back of the throat. I found the shelter by a bus stop where the benches had been cleverly designed so a person could not lie down across them and a man lay on the sidewalk instead.

Inside, the smell was bleach and bodies, soup and paperwork. The woman at the front desk looked up, assessed me quickly, and didn’t bother to tell me I was in the wrong place.

“I—someone called me from here last night,” I said. “He said his name was Tommy. He used your phone at two in the morning.”

She frowned the way people do when they want to make sure they are about to tell you the truth. “You’re David?”

“Yes.”

“He’s in the common room.” She pointed to a door at my left. “He’s been waiting.”

The room was bigger than it looked from the street. Mismatched chairs, a television on a metal cart, the sound turned low to a show that no one was really watching. A dozen men and women looked up when I walked in with the glance they give anyone who might be there to take or give. In the corner by a window, a man sat with his back to the room, shoulders up around his ears like he was trying to keep his neck out of sight.

“Tommy?” I said.

He turned. I had prepared for everything and nothing at once. The face was a map of a life lived outside: sun and wind, hunger and hard. Deep lines around eyes that were still ours. A scar on his cheek I didn’t know. The eyes themselves—brown with flecks of gold that catch when the light finds them—were the same.

“David,” he said. His mouth tried for a smile and found the shape of a different one—relief, maybe, or fear.

“Your arm,” I said because if I said anything else I might run. “Left side.”

He hesitated, then rolled up his sleeve. The old line of white tissue ran jagged where skin had closed over a story. It was not proof. It was a beginning.

“We’re doing a DNA test,” I managed. “Today.”

He nodded. “Okay.”

We swabbed cheeks in a lab with glass walls and soft chairs. The technician was kind in the way of people who have told both consolation and catastrophe to clients for years. While we waited for results that would take two days and change the rest of our lives, I booked a room at a modest hotel near Stanley Park. Two beds. A shower that ran hot and loud. He disappeared behind the door with a clean t-shirt and stayed so long I knocked once, lightly, to make sure he hadn’t forgotten to come back out.

He emerged shaved, hair slicked back with hotel conditioner, smaller somehow because the grime of anonymity can make a man look larger. The shapes were clearer now. The line of his jaw was our father’s. The ears—Carr ears—ridiculous and perfect. He and I sat on separate beds and ate pizza from the box like teenagers who had put off talking about something important and were trying to figure out how to begin.

“What was I like?” he asked after a while. Softly, like a person asking someone to read their future in tea leaves.

“Good,” I said. It surprised me that my voice held. “You were good. You cried when you saw roadkill and brought home stray cats and wanted to be a vet because you couldn’t stand to think of anything hurting. You ate more blueberries than pancakes and then insisted you had eaten pancakes. You told Mom jokes on days the bills made her shoulders slump. You promised me we’d take care of her when Dad left and then you did.”

He held his hands together between his knees like he was trying to knit them into one. “I wish I remembered.”

“Maybe you will.” I didn’t say I didn’t know if that was kindness or a lie.

He fell asleep first, a deep, clean sleep that belongs to children and men who have been safe for exactly four hours. I lay awake and watched the blinking light on the smoke detector and tried not to mistake its rhythm for a heartbeat I could fix.

Two days later, the phone rang at 2:30 in the afternoon. The woman from the lab read the numbers calmly. Probability of full siblingship: ninety-nine point nine seven percent. I wrote it down even though she said the email would include it. I hung up and looked at the man on the bed.

“It’s you,” I said. “You’re really Tommy.”

He laughed and cried at once, then covered his face with both hands and said, muffled, “I’m Tommy,” like he was trying to convince himself muscle by muscle. I put my hand on his shoulder. The human body is a strange machine. It carries memory of touch in the places words cannot reach. He leaned toward it like a plant toward sun.

“We’re going to find out what happened to you,” I said.

“I don’t know if I want to know,” he said.

“We’ll decide together,” I said, which is a thing I wished I had said to him when we were boys and I thought I had to be the one to know everything.

Part II — The Missing Years

Tommy said there was a doctor he trusted at a clinic on Powell Street. Free care. Volunteers. A woman who made space for people to take off their coats and set down their shame. Dr. Patricia Walsh had lines around her eyes the way kind people do. She listened to the whole story with the stillness of someone who understands the weight of hearing it.

“May I examine you?” she asked him. He nodded. She ran fingers lightly along old scars, pressed gently on healed ribs, tested reflexes, watched pupils, noted the depression at the back of his skull that had closed but never quite forgotten.

“Years of significant trauma,” she said. “Multiple old fractures. We don’t need your DNA test to tell us you’ve been through enough to account for a lifetime.”

“What do you think happened?” I asked. I braced for the answer like a person opening a letter in someone else’s handwriting.

“I think he survived the crash,” she said. “Head injury. Cold. Confusion. In that chaos, with faces battered and snow covering everything, it would have been very easy to misidentify a body. Especially for a young man asked to tell his mother the worst thing and desperate to get it right.”

The room pulled into sharp focus. I could see every paperclip on her desk.

“I think someone found Tommy not long after the crash and did not take him to a hospital,” she went on, voice even, words careful. “Perhaps because they were involved in something illegal. Perhaps because they saw an opportunity to use a nameless young man in remote labor. There are camps—illegal logging, unregulated construction, grow operations. Cash deals. No records. No questions answered because none are asked.”

She looked at Tommy without pity. “We know dissociative amnesia can be protective in trauma. The brain does what it must to keep the whole from fracturing completely. Pieces disappear. Time jumps. Then, around 2010, something shifted. You were found on the street, disoriented. The hospital filed what it could. You didn’t have a name to give.”

“Why didn’t I remember sooner?” he asked.

“Because remembering is dangerous,” she said. “Because sometimes it takes one line in one old newspaper to wake a part of you that has been waiting exactly forty years for permission.”

We walked out into the evening like men who had received a diagnosis. It did not heal anything. It gave our pain an outline.

“Come home,” I said, there on the Powell Street sidewalk with the smell of garbage and rain in our noses. “Come to Kelowna. Stay with Sarah and me until you figure out where your feet go.”

He stared down the street like a person who had forgotten what a horizon was for. “I don’t know how to be anyone’s brother.”

“Me either,” I said. It felt like a confession I had needed to make to someone for forty-two years. “We’ll learn.”

I do not know what made him say yes. Maybe the way his own hands had stopped shaking when Sarah hugged him on our porch. Maybe the way my grandson had declared, immediately and without irony, “This is my friend.” Maybe the smell of lemon cleaner and coffee in our kitchen. Maybe the way the bed in the spare room looked made.

On the drive back, we stopped once at the side of the road when the mountains opened out and the snow bowed away from us. “I’ve seen these,” he said quietly. “In flashes. Like a film with frames missing.”

“You’ve survived them,” I said.

At home, the complications were as steady as the comfort. Neural pathways resent being forced to carry heavy traffic after years of rural usage. He startled at small sounds, slept with the light on, stood sometimes in the doorway to the yard like a man checking the weather before deciding whether to risk it. He woke with nightmares we could not interpret and sat in the afternoon sun like a cat until the panic left his breathing. He saw Dr. Walsh twice a week on video and another therapist in town who specialized in trauma that didn’t fit neatly into a checkbox.

The past came back in petals, not whole flowers. A bicycle with red handlebars. The name of our dog—Biscuit, ridiculous and perfect—remembered suddenly while he peeled carrots. Mom’s humming when she cooked. Tom—the man he had been called all these years—cried without drama when he remembered her hands. He asked to visit the cemetery. We stood before a stone carved with the wrong truth, the grass grown around it greedily anyway. We did not move it. It felt important to leave a marker for the boy who had been dead to us even if he hadn’t been dead to the world.

I drove us to the crash site one afternoon when the winter had softened and the snow had pulled back enough to reveal the curve where all that January had changed shape. There is a small memorial there now—names, flowers faded by wind, fresh ones bright as defiance. He stood with his hand on the pole and closed his eyes. He did not remember. He remembered. It is impossible to explain how both can be true at once and more true together than apart.

At the library in Vancouver, the same librarian who had first put the old newspaper in his hands kept digging after we left. She sent me copies of RCMP reports from that winter. A trucker had radioed an accident at dawn. A witness had said they heard a voice calling for help to the west of the wreckage, toward trees. The footnote had been noted, then lost in the thick stack of hard things that had to be done that day. The librarian enclosed a sticky note: for what our system missed. I wrote back with a donation in my brother’s name.

An old foreman from a logging camp near Merritt called me after a friend of a friend put out word. He remembered a quiet kid who couldn’t remember his own name who had shown up hungry and been put to work on a road that shouldn’t have been built. “He was a good worker,” the man said. “Never complained.” Shame does strange things to a human voice.

We did not seek vengeance. The men who had used him were ghosts, and besides, there is a hierarchy to justice. Sometimes it looks like a courtroom. Sometimes it looks like breakfast at a table with a second bowl set out.

Part III — Brothers

You do not relearn brotherhood at once. It happens at the kitchen counter, both of you reaching for the same mug and laughing when you clink by accident. It happens in the garage when you teach him how to use a power drill because even though he has built a thousand illegal frames he has never been allowed to hold the tools like they belonged to him. It happens at the garden center where he gets a job because plants do not startle and the world suddenly gives your hands something to do that isn’t defense.

He came home one afternoon with soil under his nails and a story about an old man who had been buying the wrong fertilizer for years. “I told him,” Tom said, then paused as if he had borrowed the authority to do so. “He came back and said his roses thanked me.”

He asked one day, out of nowhere, whether we should take down his headstone. We sat in the car outside the cemetery and watched a groundskeeper coax a mower into obedience. “What would it mean to remove it?” he asked.

“That a story can stop being wrong,” I said. “That another can root where it stood.”

“What would it mean to keep it?”

“That the boy who died to us still deserves a marker,” I said. “Even if he didn’t die.”

We left the stone where it was. We put a small plaque beside it that read: Tommy Carr, alive. We had to leave the dates empty. We settled for the words. The groundskeeper wiped his eyes and said he’d never seen anything like it.

My daughters came to him carefully, the way you approach a stray who has chosen your porch. They brought him recipes and asked him to show them how to fix a leaking faucet because I am better at calling plumbers than replacing washers. My grandson crawled into his lap with the ease of a child who hasn’t yet learned how much of the world is imaginary. He called him Tommy because kids don’t understand the weight of names and because in his mouth it sounded like the only possible word.

We fought once, badly, about money. Trauma teaches scarcity. Every orange in the house was his favorite orange. He hoarded crackers in his room because somewhere his body remembered winter and empty calories. I found a box under his bed and told him he didn’t need to hide food. He said he did. I raised my voice. He raised his. It was not a pretty scene. We sat at the table after, both breathing like we’d run up a mountain, and he said, small, “I’m afraid of January,” and I said, smaller, “Me too.”

I took him to the workshop where I volunteer on Wednesdays—men with missing fingers and missing years rebuilding chairs with missing spindles and calling it therapy because where else do you put that word. He learned to sand with the grain, to pull a nail out slowly, to let his mouth form stories without asking permission to be heard. A man with a dragon tattoo on the back of his hand taught him how to square a corner better than I ever could. I watched Tom’s shoulders drop in a way I had not seen since he was nineteen and about to score a goal on the old school’s field.

We saw a family therapist who has a couch that has held more sadness than pews and a way of saying “and then?” that makes you want to tell the truth even when you’ve learned to hide it. She asked me to say out loud the sentence I had been punishing myself with: I identified the wrong body. She asked Tom to say out loud the sentence he had used to keep himself small: I do not deserve to come back. She had us say them again and again until the sentences felt less like facts and more like wounds. Wounds heal with care, not denial.

We drove to Mom’s grave on a Sunday that felt like a practice run for spring. Tom stood with his hand on the granite. He did not talk. I did. “He’s here,” I said to the ground because sometimes you have to speak to the part of the world that cannot answer back just to make the room for an answer. “He’s alive. He’s in my house. He eats too much cereal. He’s going to be okay.” A bird sang and my gut, irrational and loyal, called it a sign.

Part IV — The Call Back

The strange thing about miracles is that they look nothing like the pictures. My brother’s return did not come with trumpets. It came with Tuesdays. It came with thin wrists and a sweater he loves because it has pockets that make him feel like his hands belong somewhere. It came with a library card. It came with the way the dog follows him into the yard and lies down near his feet like she understands that being near him is something we get to choose.

Sarah—who has been married to me for thirty-eight years and has put her hands on my shoulders the way you steady a man who leans—started keeping blueberries in the house again. She makes pancake batter on Sundays we can all be home. Tom eats two before they are off the griddle, presses his fingers to his mouth in mock guilt, a boy’s gesture inside a man’s body. We laugh like people who haven’t had that sound available to us in a long time.

The DNA lab sent a hard copy of our results because I asked. It sits in a file in the safe along with birth certificates and the first drafts of our wills and the letter from Grandpa that changed my whole idea of what money is for. Sometimes I take it out and hold it not because I need proof but because paper has weight and weight can lend a moment the gravitas it deserves when your insides go to water.

I called the RCMP in Merritt and asked whether they still had an open file on the crash. A sergeant called back two days later with the tone of a man who has been a cop long enough to know the difference between formed and forming to ask intelligent questions without promising comfort. He listened. He did not say justice like a carrot he could dangle. He said words like closure and follow-up and if we find something. It was enough. It had to be because the past is a country with porous borders and we have chosen to live here now.

We held a small thing in our yard in June. Three folding tables, paper plates. A few people who had searched with us when we were young and didn’t know which end of a shovel was best for digging hope. A handful of Tom’s friends from the street who actually answered my letters to shelters because they have a network far stronger than people in suits understand. My daughters. Their kids. Tom stood beside me and said into the space between all our breaths, “Thanks for picking up the phone,” and then laughed because we had begun to believe that it is allowed to find joy stupid and simple.

I answered a call at two in the morning and it gave me my brother back. This is the part where a writer is supposed to give you a sentence to carry, something stitched to your insides like a label. If there is one, it is this: never apologize for leaving the light on. The world will convince you it’s a waste of electricity. But sometimes a man lost in his own life will look up from the corner of a shelter’s common room and see a window glowing and walk toward it.

We do not know what we will do with the headstone. We talk about it every Tuesday in therapy and every third Saturday on the drive to the garden center because routine makes heavy things bearable. Maybe we will leave it. Maybe it can be a place we go when we want to remember the part of the story that still hurts because grief doesn’t vacate a house just because joy moves into the spare room. Maybe we will replace the dates with a line: He wandered. We waited. He came home.

My brother was buried forty-two years ago. Last week he called me and told me his name and the world blinked twice and did not fall off its axis. It is not perfect. He has days when the shadows pull more weight than he can carry. He sits on the porch and watches the street until the shape of it returns to something he can live in. I sit beside him and say nothing because nothing sometimes is the exact size of the love you need to offer. We go inside. We eat pancakes. We make a plan for tomorrow because tomorrows are how you build a future you once thought you had been robbed of.

In our family photo album, there is a picture of two boys. One has blueberry on his chin. The other is pretending he knows the answer to a question his teacher didn’t ask. A few pages later, there is a grown man with a shovel breaking ground on a place that will teach men how to fix chairs. In the back pocket, a folded newspaper clipping that once defined us now sits under a printed lab report that explains us.

I told my story to a man at the hardware store who asked how I was when he should have asked if I needed nails. He said he had a sister he hadn’t called in years. He said it like a confession and a dare. I told him to call her. He nodded, looked at that spot right over my shoulder where men look when they are trying not to cry in public, and said he would.

I don’t know if he did. I know I did. And my brother’s voice, when he said his name to me at two in the morning, sounded like the first time in a long time that either of us had been allowed to tell the truth.

Tommy is home. He is in my house and in my life and in the long project of learning how to live in a body that has survived. He plants tomatoes and gets soil under his fingernails and laughs when the dog sneezes. He is remembering who we were. He is building who he will be. And when I cannot sleep, I go to his door and listen for his breathing and I am twenty-three again and nineteen again and sixty-five and fine. Because the sound is steady now. Because the house can hold it.

We do not get our dead back. We get something stranger and more holy—we get a chance to love the living in front of us with the urgency we learned from loss. My brother was buried forty-two years ago. He is sitting at my kitchen table right now, circling the crossword with a pencil too hard and telling me I don’t know the capital of Yukon. We argue it out. He’s right. He laughs. And my world—our world—stops and starts again the way it should.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Dad and “Deadbeat” Brother Sold My Home While I Was in Okinawa — But That House Really Was…

While I was serving in Okinawa with the Marine Corps, I thought my home back in the States was the…

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash Part 1 The scent of lilies and…

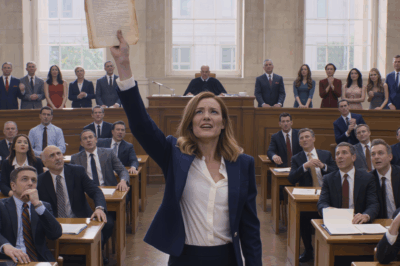

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court…

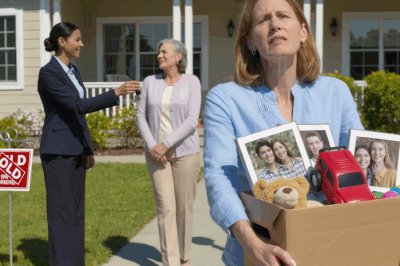

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It Part 1 The email hit my inbox like…

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”?

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”? Part 1 The email wasn’t even addressed to me. It arrived…

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last Part 1 The…

End of content

No more pages to load