My Brother Said Dad Would Cut Me Off. He Didn’t Know About the USB.

Part I — Lilies, Lies, and a Draft Email

The lilies were too sweet. The funeral home pumped their cloying perfume into every corner, a floral fog laid over grief like icing on stale cake. Black suits, black veils, black coffee. Black hearts, too, if you looked long enough.

My brother’s voice knifed through the murmur. “She’s just here for the money. Dad was going to cut her off.”

Heads turned like sunflowers. Some pitied me. Some sneered. Most watched the way people always watch, ready to eat whatever came bleeding out next.

I didn’t give them anything. Not a twitch.

The door at the end of the room opened. In walked our father’s lawyer, Whitcomb—stooped, meticulous, with a faith in paper rivaled only by priests and actuaries. He carried a slim gray USB drive between his finger and his thumb like a fuse he wasn’t yet ready to light. The projector on the credenza hummed to life. The wall filled with static.

I could feel Daniel, two chairs to the left, wind up for another swing. The same boy who held my hand under blankets during August thunderstorms had grown into a man who believed thunder was applause. Time corrodes love; money polishes the rust.

It hadn’t always been like this. There were years when we were a two-person gang: climbing the apple tree behind the garage to spy on the neighbor’s lunatic rooster; tipping Dad’s work boots on their sides so the mice that had nested in them would be evicted; stealing Mom’s sugar cubes to feed to horses tethered by the fence after the county fair. Then we learned you could win a home with the right kind of smile. Then Dad got sick, and then the math got messy.

When the diagnosis came, I moved back into the house with the peeling porch. I worked days at the clinic and nights in a chair next to the one he breathed in. I learned to measure pills in grams and time in breaths. I boiled broth. I scraped my patience thin and spread it generously. Daniel visited on Sundays, when he wasn’t playing golf or making promises he wouldn’t keep to women who called him Dan in a way that made Mom roll her eyes.

Dad noticed. He always noticed. He noticed the checkbook entries that weren’t his; noticed the way Daniel’s eyes had started calculating when he thought no one else was multiplying. He noticed that his accountant had questions most sons would have had the sense not to prompt.

The first whisper arrived in the shape of a bank statement. Three cash withdrawals, each one conveniently under the threshold that triggers a call from a computer with a voice that knows your birthday. Dad pressed his finger to the paper like it might find a pulse.

Then I found the email.

Dad had dozed off in his recliner. The laptop hummed in the faint sunstrip. The mouse stirred the screen and there it was: Daniel’s Gmail, left open on the family computer because arrogance and carelessness wear the same shoes. A draft to a lawyer. Not Whitcomb—not Dad’s lawyer. Subject line: Ensuring My Sister Receives Nothing. Body: She’s manipulating Dad. We need to make sure she can’t inherit. Suggest options.

The betrayal didn’t burn. It froze. It wrapped around my ribs and squeezed until I remembered to breathe.

I didn’t confront him. Not yet. I learned, finally, to play silent.

That evening, spooning broth past Dad’s stubborn mouth, I told him everything—about the bank, about the draft, about the tone Daniel had learned to use that made every room a stage.

Dad didn’t flinch. He lifted his hand the way men lift hammers: sure of the nail. “Give me your phone,” he whispered, voice a piece of sandpaper. “Record me.”

That night, his face—thinner than it had ever been, still somehow bigger than the room—filled the lens. He spoke the truth as if confession could build a bridge sturdy enough to outlast him. He told the camera what he’d seen and what I had done and what Daniel had done. He told the camera our history and his diagnosis and his mind’s clarity. He told the camera the one line you could measure a family by: “Blood means nothing without loyalty.”

I saved the file. He wanted more.

He asked for Whitcomb. He asked for paper. He asked for something the law recognizes when the heart decides it’s done pretending. The USB was his idea. A clean copy. A last word.

The day after Dad died, I visited Daniel. His townhouse smelled like cigars and expensive musk and the arrogance of someone who’d never sweated for a thing he owned. He swirled whiskey in a glass he called a Glencairn like it was the stagehand for his performance.

“You think you’ll get anything?” he asked, generous with contempt. “Dad knew what you were after.”

I smiled and let my eyes move across the wall of framed certificates and headlines—the foundation of his reputation, all held up by the illusion of integrity. I didn’t say a word. Leaving him his fantasy made the fall sweeter.

And now, the funeral home. The lilies. The clink of Whitcomb’s old man shoes on tile.

“Thank you for your patience,” Whitcomb said, inserting the USB. “Mr. Harrington left instructions.”

The projector hummed. Pixels gathered. Dad’s face appeared—a ghost that didn’t blink. Gasps fizzed through the chairs like shaken soda.

He spoke.

He spoke about Daniel’s greed in language with no adjectives, the way a man who earned his money rather than invented it speaks. He spoke about the thefts, the rewritten ledger entries, the Sunday visits that shrank. He spoke about my nights in the chair, my soup, my temper, my patience. He did not cry.

He ended with three words that sounded like a gavel and felt like a blessing.

“She deserves everything.”

And the will—the paper version—said the same in more syllables: Every asset, account, and key to me. To his daughter who had stayed. To the child he’d measured in loyalty rather than blood type.

Whitcomb read the list with his lawyer voice. People looked at Daniel, then at me, then at the exits. Daniel went white like his collar. He startled forward, voice cracking where charm usually sits.

“This is forged,” he shouted, reaching for the USB as if bytes could be wrestled into new shapes. “She tricked him. He was dying.”

“Recorded in my presence,” Whitcomb replied, calm as a beached log. “Signed. Witnessed. Legal.”

Whispers poured through the room, a storm surge of gossip. Daniel’s colleagues pretended to discover fascination with their tie clips. His mistresses checked their phones. His supposed friends did the cruel math people do when a benefactor collapses: What does this mean for me?

I leaned in, just enough for him to hear me over the projector’s fan. “You wanted me cut off,” I whispered. “Turns out it’s you who’s severed.”

His glass chose the floor. He chose the door.

I let him go.

Part II — The Domino Line

That night, I sat in Dad’s study with the USB in my palm. The old desk smelled like tobacco and lemon oil and a thousand decisions. Revenge isn’t loud. It isn’t a speech. It is a room emptied of watchers and a choice to do nothing when everything is begging you to swing.

Within a week, I didn’t have to.

Investors began calling Daniel to reschedule lunches and then didn’t. A story appeared on page three of the business section about “irregularities” at his firm, which page three is where reputations go to die slowly. A woman with impeccable nails sold a bundle of texts to a tabloid that prints lipstick and litigation with equal glee. His friends turned vultures, circling an ego too busy bleeding to shoo them away.

I did nothing. I answered no calls from unknown numbers. I hired a gardener for Dad’s hydrangeas. I took the dog for longer walks. I listened to the house remember how to exhale.

Of course, there were calls from the family branch that never learned humility. Mother: “Drop this nonsense. You look cruel in black.” Aunt Claire: “This will haunt you, darling.” Uncle Vince: (three bourbons in) “We Bl— Harringtons don’t sue our own.”

I refused to explain to people who’d never listened. I’d already done my talking where it counted.

Three weeks after the funeral, I found the first check in Dad’s desk—a small refund from a contractor who had overcharged him. It made me cry harder than the USB. Kindness is always quieter. It ruins you in better ways.

I paid the hospice bill. I sent Ms. Delaney—the nurse with the blue shoes—flowers. I changed the locks.

The day I went through Daniel’s email (left logged in on the family computer again because some men do not grow), I found more drafts to lawyers than any sane man should have. In one, he had written We need to ensure she gets nothing, sent it to his own address, and then I presume practiced reading it aloud in a mirror.

He had wanted to cut me off so badly he’d eventually borrowed a knife that fit his own throat best.

Part III — What an Inheritance Actually Is

I didn’t spend the money. It felt like bones. I moved through the house and listened to what needed care: the gutter that pretended not to be clogged; the bedroom window that stuck on days it rained then got hot; the garage door that didn’t know stop. I repaired things because things in this family had been breaking for a long time.

Around the time the April light turned honest, I took a box of Dad’s old 8mm tapes to be digitized. I watched us in jerky color: Dad tossing tiny Daniel into lake water, then tiny me squealing in outrage that he had been trusted with air; Mom younger and less weaponized by the years, laughing so hard she made no sound; Daniel holding my hand when thunder yanked the sky loose; me pushing Daniel up the hill on a red bike he swore he could ride without pedals.

We were children holding hands in water. We had not yet been taught which hands to let go of.

The day the last of Daniel’s investors left him with a press release and a shrug, he called. Blocked is a wall that does not argue. He tried a new number. “You did this,” he said when I forgot for a second to let unknown calls go to an empty room. “You destroyed me.”

“No,” I said. “I stopped protecting you from yourself.”

He hung up. It felt like more of an ending than Whitcomb’s three words ever had.

Months later, I met a young woman on the porch. She was pale with purpose. “I’m Sarah,” she said, hugging a folder. “I’m taking care of my mom. Your father—he used to come by the diner where I work and give me a twenty-dollar tip for a ten-dollar check and tell me to ‘bank the difference’ because ‘savings buys choices.’ He told me to come to you if I ever needed… advice. On the money. Or the letters.”

We sat. I made tea. We sorted. She left lighter. Dad would have approved. The real inheritance wasn’t the account the lawyer read numbers from. It was the habit of noticing—who needs a door held, who needs a fence mended, who needs a sentence that says what you did mattered spoken in a voice that doesn’t tremble.

Part IV — The Last Cut

On the one-year mark, I took the USB from its drawer and held it up to the light. It looked like nothing—a stick of plastic with a metal tooth. On it, a man told the truth out loud. A year ago I had needed those bytes like oxygen. Now I needed them like a story I had, thankfully, already heard.

The house is mine. The photos on the mantle have been rearranged. Daniel still exists in them in a tie too wide and a grin too certain. I didn’t remove his face. I removed his gravity.

Sometimes a storm rolls across the lake and I remember those thunder nights—the way he let my hand press into his palm. I can hold both truths: he saved me once from being afraid of loud, and then he became a loud I had to stop being afraid of.

People ask if I regret the ruthlessness—cutting him off in a room full of lilies. They think regret is a moral they are owed. I tell them this: lily fog makes a person feel like they’re floating. USB light brings the floor back.

At dusk, I walk the backyard and flick the tree lights on one by one. The neighbors look through the fence and wave. Sometimes I nod. Sometimes I invite them for lemonade. Once, a child pointed at the projector screen on the side of my garage where I’d been testing it—not with wills or confessions, just with old home movies and a terrible rom-com with rain that made no meteorological sense.

“Is that your dad?” the child asked.

“It is,” I said.

“Is he nice?”

“He tried to be,” I said. “And in the most important moment, he was brave.”

Daniel is learning the cost of losing both. He sells the car he couldn’t afford. He posts quotes about resilience under photos of sunsets that aren’t his. He joins a gym, then a men’s group, then a church, then another gym. People who once called him sir now call him Dan like it’s a verdict.

I don’t hate him. I don’t attend to him. I let the tide do what the tide does.

As for me, I measure days differently now. Lilies smell like lilies again. The projector sits on a shelf, quiet, its work done. The USB rests in a drawer with the measuring tapes and the spare batteries, among all the ordinary tools that make a house run.

And when, on some future day, someone in some other room thinks “She’s just here for the money,” I hope a lawyer somewhere plugs in a small piece of plastic and a voice like a hammer says the words that free the daughter holding her breath:

She deserves everything.

Then I hope she walks into her own house and sits down and exhales and knows—finally—that everything includes peace.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

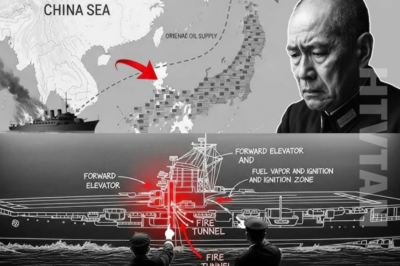

CH2. The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight

The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight The convoy moved like a wounded animal…

CH2. How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster Liverpool, England. January 1942. The wind off…

CH2. She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors

She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors The Mediterranean that night looked harmless….

CH2. Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming

Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming December 4th, 1944. Third Army Headquarters, Luxembourg. Rain whispered against…

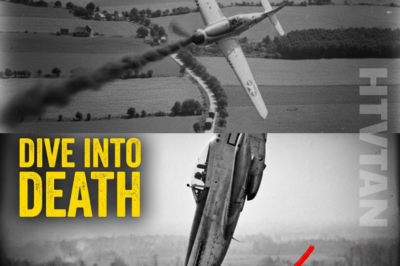

CH2. They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass

They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass The Mustang dropped…

CH2. How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat

How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat The North Atlantic in May was…

End of content

No more pages to load