My Brother Laughed at My Father’s Funeral—Then a Nurse Handed Me an Envelope That Changed Everything

Part I

At my father’s funeral, grief didn’t arrive the way I expected. It came in fragments: the weight of lilies, the dry rustle of suit fabric when mourners shifted, the way candlelight flickered on the polished wood of the casket as if it were breathing. And then it arrived like a blade—my brother’s breath at my ear and the sentence he sharpened on his tongue.

“He left her nothing,” Lance said, loud enough for the pew behind us to take it as small-town gospel. “She never meant anything to him.”

I stared ahead at the altar. Saint Jude peered down from stained glass, patron of lost causes, and for the first time I wondered if he’d been looking at me all along. I folded my hands and counted my breaths. I would not give my brother the entertainment of a scene. We were there to bury a complicated man. I wouldn’t resurrect a simpler cruelty.

David Thorne had several versions depending on who told the story. The man in the eulogies mentored interns and wrote checks with an old-fashioned fountain pen. The man in headlines steered acquisitions that saved floundering companies and closed doors on those too tired to swim. The man I knew—the one who forgot my birthday the year after my mother died, who praised Lance’s first tie like it was a Harvard diploma—was quieter. Absence isn’t silent; it hums. It had hummed through my childhood like the refrigerator at night, constant and unignorable.

After the service, the will reading was practical and perfunctory. Mr. Carile’s hair was the kind men pretend isn’t dyed; his briefcase looked like it had carried secrets for half a century. He opened it, took out a single thin folder, and spoke my father’s last legal sentences into a room too small for them. The estate, the business, the house—Lance. A trust with provisions to ensure continuity—Lance. The classic “to my beloved children, I leave my blessing”—a phrase that felt borrowed from a family that used that word without choking on it.

I waited for an addendum. I wanted it not as money but as acknowledgment. There was none. Lance turned slightly, the smirk he’s had since he learned he could carry a room with it. When we were children, that smirk had meant he’d stolen the last cinnamon roll. Now it meant something heavier: victory.

And then a woman I didn’t know stepped forward, cutting through the murmur like a small, precise ship. Her name badge was clipped to navy scrubs: Mallerie, RN. She held a white envelope in both hands as if it were a fragile specimen she had ferried through chaos. “Are you Amira Thorne?” she asked, looking only at me.

“Yes.”

“Your father asked me to deliver this to you and only you.”

It shifted something in the air. Lance straightened. Mr. Carile raised a brow; our aunts—those perpetual whisperers—whispered. I took the envelope. My name was written on it in my father’s sharp, slanted hand, the black ink blotted once where the pen had hesitated. The sight shook me harder than the eulogies. He’d written my name recently enough for the ink to still look wet in my mind.

Lance chuckled, an ugly sound inside a sacred room. “Probably some sentimental nonsense. It doesn’t change anything.”

“Then you won’t mind if I read it alone,” I said, surprising both of us. I tucked the envelope into my coat and stood.

Outside, the funeral home’s garden was the kind of quiet you only find behind buildings meant to hold tears. A winter fountain ticked. I sat on a bench and slit the envelope with my thumbnail. The paper gave like a breath. Inside were three things: a letter, a brass key, and a photograph.

The photo stopped me. I was six, knees green with grass stain, perched in Mom’s lap, both of us splattered with paint. She’d used my palms as stamps, pressing them onto paper until I giggled. My father had taken the photo—this I remembered now in a flash: him leaning in the doorway, the camera’s shutter a click like a door unlocking. He’d disappeared immediately after. The picture was proof he’d been there at least long enough to frame us.

The letter began simply. “Amira. If you’re reading this, I couldn’t say it in time.”

It wasn’t eloquent. My father’s letters to clients had been works of art—bland flattery lacquered over iron strategy. This was raw, the ink heavier in places where he must have pressed too hard. “I failed in many ways. The worst was how I treated you. I told myself distance would make you strong. Truth: I was afraid. You were your mother’s pulse—bright, loud, impossible for a man who made his plans in silence to hold.”

I paused. The wind laced fingers through the boxwood hedge and the world went quiet enough for the sentence to lay down inside me.

“I kept every story you sent,” he wrote. “I told you once there was no money in writing. I was wrong. The wealth you carried was never going to be a ledger I could read, but it was there. It always was. The key opens the cedar chest in my study. The chest holds your mother’s journals. It holds something else: my attempts to say what I wouldn’t. I tried to change the will. I was late for many things. I was late for this, too. Nurse Mallerie helped me record what I couldn’t sign. I don’t expect forgiveness. I hope for understanding. I love you.”

The letter shook in my hand. I found the woman who had delivered it and asked her to walk with me. “He talked about you,” she said as we went down the steps. “He didn’t talk like a CEO. He talked like a man counting what he’d missed.”

“You knew my father for weeks,” I said, no bitterness, only marvel. “You knew him more than I did in some ways.”

“I knew a man who tried,” she said. “Sometimes that has to count.”

Back in the room, Mr. Carile swiveled as if warmed by the idea of a complication. Lance scowled as if the universe had broken a rule designed for him. “We have recorded testimony as well,” Mallerie said, lifting her chin.

“That has no legal—” Lance began.

“—standing,” Mr. Carile finished for him, “unless the court finds it persuasive, which, given a nurse’s statement, it might.”

“I’m not here to fight for money,” I said, and to my own surprise, it wasn’t a performative line. The envelope had changed my calculus. I had no appetite for the meat of inheritance; I was hungry for its marrow.

Part II

The house on Ridgeline hadn’t aged since the last time I stood at its door, which seemed unfair. People should outpace structures. Greystone preened in good light. The portico’s columns—the ones Lance had joked were phallic when we were thirteen and bored—held strong. If I held my breath and squinted, I could see movement behind the curtains, but it was only memory.

The study had always been a place we weren’t allowed. There are rooms in certain houses that look more like a theory than a space. This was one. Bookcases floor to ceiling, an antique globe fixed stubbornly on some forgotten border. Diplomas. A framed front page from the day the firm went public. The cedar chest sat under the window like an obedient dog waiting for a command.

The brass key slid into the lock with a softness that made me bite my lip; some part of me had expected resistance. The lid lifted. The smell hit me first—cedar and paper and the faint metallic tang of dried paint. There were folders, canvas rolls, a flash drive, three leather-bound journals tied with faded ribbon I recognized from a box of my mother’s things: she had collected ribbons the way people collect seashells.

The first journal almost undid me. Elise Thorne wrote in long lines that curled and dipped like music. She wrote about Lance and me with specificity: the way I hummed without knowing, the way he counted stairs; the way she loved cooking best on Wednesdays because the week had settled and the onions didn’t make her cry then. She wrote about fear too—the wrong kind of silence in my father, the way grief had moved into the house after the diagnosis and refused to pay rent.

A folder labeled FOR AMIRA contained all the things he had claimed not to have time for. My first published short story printed, stapled, annotated: “This held me,” he had scrawled in the margin next to a sentence I’d loved too. My grad school personal statement, underlined in places where I had hated my own earnestness. A poem I had written about my mother’s hands with an “ouch” in the margin and then, in smaller letters, “yes.”

“I’m not crying,” I said out loud to a room that would not lie on my behalf. I was crying.

At the bottom of the chest, a flash drive waited—labeled FINAL in block letters, which felt on-brand for a man who’d spent his life naming things with tidy efficiency. I plugged it into the old laptop on the desk—the one with the key click I could hear from upstairs as a teenager when he worked late. My father’s face filled the screen, thinner, eyes ringed by something hard-won. He looked directly into the camera.

“Amira,” he said. “It’s a habit, I think, to believe you have more time. I’m not going to waste yours now. I’m not giving you instructions. I’m giving you permission. The house—do with it what your mother would have. The journals—share them if you want or burn them if that’s kinder. The business goes where it goes. Lance knows how to handle numbers. What he doesn’t know is how to tell the truth about them. You do. I don’t expect you to forgive me for learning too late that I live in a family and not a ledger. I hope you’ll let yourself be seen by someone who deserves it. If that someone is me, now, for a moment in a grainy video, let it be. If it isn’t, that’s on me.”

It ended there, without music, without a fade-out, just my father’s face frozen between speaking and breathing. I watched it twice. The second time, I noticed his hands—always busy during meetings, always folded during dinner. Here, they were open on the desk, palms visible. It felt like something religious without the trappings.

Lance arrived with a lawyer and an expression that had gotten him out of countless mistakes. The lawyer—sharp suit, sharper smile—tried to shove the conversation back into rails. “Without a codicil—”

“—we have a video,” I said. “We have a nurse. We have a chest full of testimony the court won’t be able to ignore. We have intent.”

Lance swallowed. It was small, that movement. It made something in me uncurl for him and then curl back. He was a boy I’d played hide and seek with inside this very house, counting past ten while I held my breath behind the curtains in the music room, the ones Mom had stitched herself. He was also a man who had told people I didn’t mean anything to our father. Both were true. My grief had to hold both.

“What do you want?” he asked finally, the lawyer’s mouth pinching like he wanted to smack the word out of the air.

“The house,” I said, surprising everyone including myself. “Keep the money. Keep the company. Keep the gratitude of a board that will forget your name in five years. I want the center of our story.”

“That’s not—” the lawyer started.

“It’s possible,” Mr. Carile said from the doorway, a neutral angel arriving late. “If both parties agree. The court won’t balk at a settlement that honors intent.”

Lance stared at me like I’d spoken some language he hadn’t bothered to learn. We signed papers while Saint Jude’s afternoon light turned the room honey. It felt like laying down a weapon and picking up a shovel. There’s work in making a place livable. There’s work in turning anger into walls that keep out the right things.

Part III

Grief, once the legal dust settles, is mundane. It’s calling the plumber because old houses are vain and need attention. It’s realizing your mother wrote recipes in shorthand only she understood and translating “pinch” into salt you can taste. It’s sitting in a study that had been a fortress and opening its windows because you’ve decided air is not an enemy.

I sat at the desk and made a list. Not of tasks, though there were many. Of ways to fill a silent space so it stops humming at you. Paint the study a color my mother would not have called “funeral chic.” Invite the neighborhood kids in on Thursdays with notebooks and cheap markers. Put a big battered table in the middle of that room so that other people’s elbows can bump. Make the doorway less of a law. Leave the chest unlocked.

Word travels. One kid tells another. In six weeks, I had three regulars. In three months, ten. We read Neruda and Ocean Vuong and the notes from my mother’s journals where she’d written to herself like prayer: “Elise, be gentler.” We broke and mended. We learned that rewriting a sentence feels a lot like forgiving a person; there’s a grace in it.

Mallerie came by sometimes after her shift, the faint disinfectant scent of the hospital clinging to her. She left cookies like a thief of kindness and never stayed long. She had entered my life holding a single envelope and declined every offer to stay in the story. Her name remains on my Christmas card list anyway.

Lance sent a letter eventually. It was terse in the way men write when they don’t understand that brevity is not the same as courage. “I didn’t know,” he wrote. “I know that doesn’t fix it. I’ll keep the firm out of your hair. I meant what I said when we were kids. You’re a better storyteller than me.” I read it at the kitchen island while eating cold pizza and laughed out loud because the second part was the first compliment he’d given me since he told me his third-grade drawing of a tank was “more realistic” than my unicorn.

I published a book. It wasn’t the one I thought I’d write when I was twenty and feral with ambition. It was a collection of my mother’s journal entries and my essays braided like rope. We called it The Chest Under the Window because that’s where the story turned. It sold exactly as many copies as a book like that sells. A handful of letters arrived from women in different towns in different kitchens saying they had never seen their own fathers until death made them look.

One morning, months after I’d opened the envelope in that quiet garden, I ran my thumb over the photo of me in paint on my mother’s lap and took it down off the mantel. There’s a scratch on the corner where someone long ago, probably me, probably on purpose, had scrapped a little mark. I held it under the lamp at the desk and for a reckless moment imagined the life where my father had opened the envelope for me years earlier, alive, at that desk. It didn’t lessen this one. It just existed, parallel. People talk about closure as if it is a door you lock and put the key on a hook. I think it is more like a window you open even in winter.

The cedar chest absorbs light differently now. I caught myself one afternoon sitting on the floor with my back against it, reading the poem my mother wrote about the blue bowl in our kitchen. It wasn’t a poem about a bowl. It was a poem about leaving. She wrote that the bowl would outlast her, that it would end up in a box marked KITCHEN and then in a hand marked DAUGHTER. I got up, went to the kitchen, found the bowl, and made soup.

Part IV

On the first anniversary of my father’s death, I went to the cemetery alone. Grief had gotten quieter, turned from a crowd into a person I could sit with. I brought no flowers. I brought a letter addressed to David Thorne, which felt formal and finally correct. I read it there under a sky the color of old envelope paper.

“You should have said it sooner,” I wrote. “But you said it.”

After, I drove to a coffee shop Lance and I used to go to when truce was possible in small doses. He was already there, a man who had learned to make his own coffee but still called other people and said, “You’re on mute,” as if it were a crime. We sat. He wore a wedding band now; I hadn’t been invited to the ceremony and I was still deciding if that hurt. He spoke in sentences his wife probably taught him. “I’m trying,” he said. “I don’t think we were given examples of that.”

“We were,” I said, and watched his confusion. “She sang while she cooked.”

He swallowed and nodded. That night, he sent me a photo of the cinnamon rolls he’d attempted. They were a disaster. He’d used baking soda instead of powder. The tops were pale and the centers wet. I laughed so hard I cried and sent him our mother’s recipe with the word powder underlined three times. In the kitchen of a house that had been a courthouse, the sound of my own laughter startled me with its normalcy.

The study’s Thursday nights grew. Sometimes there were five. Sometimes twelve. Once, thirty. We dragged chairs from everywhere and people sat on the floor and by the door, notebooks open, heads down, willing their insides to be brave in ink. We did prompts like “write the thing you can’t be forgiven for” and “write the phone call you wish you could take back.” We wrote the dead alive for an hour and then let them go again gently. We ate cookies that came in tins and cookies that came in greasy paper bags, both sacred.

One night, a high school senior named Jai read a piece about her father, who had left in the way some men do—just enough shirts missing from the closet to tell you what you already knew. She looked at me afterward and said, “Is it bad that I want him to come back just to apologize?”

“It’s human,” I said. “It’s also something you can live without and still be whole.”

When everyone left, the house sighed in that way old houses do—air settling as if the building were a big animal curling up. I washed cups and thought about that first winter night in the funeral home’s garden. I thought about my father’s handwriting and the photograph and the key warm in my palm. I thought about the way an envelope can be a door if you’re brave enough to open it in the right place.

I tell people now, when they ask about legacy, that I kept the house. It is the simplest answer and the most true. I kept the room where my father kept his silence. I filled it with voices. I kept my mother’s journals and did not hoard them. I kept my father’s letter, and sometimes, when the house is too quiet and my grief tries to hum at me again, I open it and just look at my name written in his hand, proof that at least at the end he knew how to write it with love.

Lance keeps the firm humming and sends holiday fruit baskets that are always more expensive than they should be. We spend Thanksgiving together now—with burnt rolls and awkward grace said too long and teenagers who pretend not to notice every adult in the room trying. It is a mess. It is also something we made. That feels like more inheritance than a check.

In the end, what changed everything wasn’t the will and its legalese. It wasn’t even the chest with its cargo of memory. It was a nurse in navy scrubs who carried an envelope like a sacrament. It was a man, flawed and late, choosing to speak. The world will tell you money is the loudest proof of love. Sometimes it is an envelope pressed into your palm with the authority of someone who stood at a deathbed and believes the living deserve the last good words.

If you found anything of yourself in mine—if you have a chest under a window you’re afraid to open—may this be your permission. The things we inherit are not always what the court counts. Sometimes they’re the things we thought we lost and then, years later, find in a letter that says simply: I’m sorry. I love you.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. HOA Karen Calls 911 After Her “Master Key” Can’t Open My Lake Cabin — Unaware My Son Is The Sheriff!

HOA Karen Calls 911 After Her “Master Key” Can’t Open My Lake Cabin — Unaware My Son Is The Sheriff!…

CH2. You Earn $3K, Why Is Your Child Hungry? DAD Asked “My Husband Proudly Said, I gave Her Salary To..

When Dad came to take my son for the weekend, he opened the fridge — it was completely empty. Shocked,…

CH2. I Gave $100 Gift at My Sister’s Birthday—Then Dad Snatched My Crutch & Kicked Me Out—But Then…

I Gave $100 Gift at My Sister’s Birthday—Then Dad Snatched My Crutch & Kicked Me Out—But Then… Part I…

CH2. Stepmom Held My 8-Year-Old’s Hands on Hot Stove for Taking Bread—Then Camera Footage Shocked Cops

Stepmom Held My 8-Year-Old’s Hands on Hot Stove for Taking Bread—Then Camera Footage Shocked Cops Part I The automatic…

CH2. My Father Slammed Me Into a Wall at My Sister’s Wedding—Then the Video Hit 5 Million Views

My Father Slammed Me Into a Wall at My Sister’s Wedding—Then the Video Hit 5 Million Views Part I…

CH2. Sister Announced, ‘You’re Evicted,’ At Dinner, While Her Kids Planned Pool Parties In Our Garden…

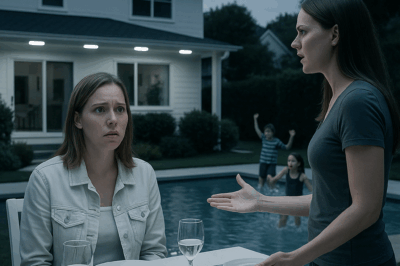

Sister Announced, “You’re Evicted,” At Dinner, While Her Kids Planned Pool Parties In Our Garden… Part I The house…

End of content

No more pages to load