My brother jeered my inheritance, saying he’d get the house and dad’s business; until the lawyer…

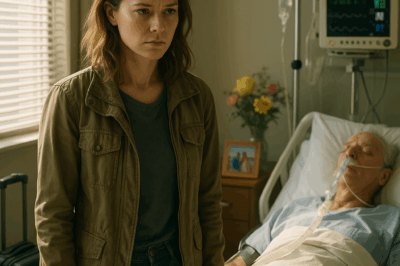

Part I — The Room Where I Was Meant To Vanish

The mahogany panels in Jennings & Hart’s conference room had heard the Montgomerys at their worst—contracts fought over, apologies offered too late, toasts raised too soon. That morning they got a performance. Sebastian tipped in his chair, expensive tie squared like a medal he believed he’d earned by being born first, and delivered his line to the gallery of aunts and cousins:

“I’m getting the house and the business. She gets the dolls.”

Laughter broke like weak glass. I tasted copper where I’d bitten my tongue. In a black dress that looked like background, I sat in the corner, the family’s designated calculator and paper-pusher, a spectator at my own disinheritance.

“My name is Ava,” I told myself in the inside voice I used on job sites when a foreman forgot I knew how to read a blueprint. “I built the last decade out of 18-hour days and 2 a.m. calls. I held the line while he held his breath underwater in Ibiza.”

Mr. Jennings cleared his throat. He was built like a wire hanger draped in tweed, kindness tucked behind excellent eyesight. “Before we proceed,” he said, “I need to clarify something material.”

Sebastian’s grin widened, certain he was about to be praised in legalese. “Go ahead.”

“The company was never in your father’s name at the time of death,” Jennings said. “Montgomery Builds is not part of this probate.”

Silence became an animal in the room—four-legged, heavy, watching.

“What?” Sebastian’s voice cracked on the vowel.

“A transfer was executed five years ago. Your father restructured ownership then.”

“To who?” Aunt Beatrice demanded, already reheating an outrage.

Jennings looked over his glasses at me. “To Ava.”

The room clicked through disbelief like an old slideshow. Sebastian looked from the lawyer to me and back, trying to make the math of his life add up.

“That’s impossible,” he laughed without laughing. “She’s the bookkeeper.”

Words I knew by heart. Words that used to sting. Now they landed and slid off like rain on waxed canvas.

Jennings set a file on the table, thick enough to doorstop a house. “Miss Montgomery has been the sole owner and operator of Montgomery Builds since September fifteenth, twenty nineteen—at your father’s direction. He cited continuity, creditor protection, and experienced management.”

Experienced management tasted like honey and salt.

I remembered the day Dad slid the transfer documents across his desk, hand trembling from the first surgery. “You already run it,” he’d said. “I’m just catching the paperwork up to the truth.”

I’d thought about the way he stared at his briefcase in the hospital and told me, “The dolls, kiddo. They’re not just sentiment.” I’d nodded, wondering why he was thinking about my grandmother’s glass-eyed darlings while the IV beeped. Now the chessboard appeared, all at once.

Sebastian leaned forward, disbelief curdling to anger. “This has to be—”

“Legal,” Jennings finished for him, gentle as a scold. “Notarized. Recorded. Effective.”

I exhaled for what felt like the first time in years.

Part II — The Transfer You Didn’t See

Dad built Montgomery Builds out of a secondhand truck and ten knuckles that never healed right. He raised a son who carried the family name like a mirror and a daughter who carried it like a tool belt. I learned the language of rebar and permits. He let me. When Sebastian announced a sabbatical to Thailand to “listen to the ocean of himself,” I listened to lenders. When a $20 million development threatened to crater under permitting errors, I camped at City Hall and learned the first-name basis of the people who actually pull levers.

On the day of the transfer, Dad had pointed at a paragraph. “Key-man insurance triggers here if I go under a bus. This clause protects the crews if we hit a cash squeeze. This—” he tapped the third line “—keeps the business out of probate. Family can fight over couches and china. They don’t get to fight over payroll.”

He kept it quiet because he knew the noise it would make. He knew, too, the gravity of assumption in a family that liked its stories neat: golden boy, brainy girl; he leads, she supports. He sent me home with the file and said, “There’s a time to build and a time to let the building speak.”

The building spoke now.

“We should move to the rest of the estate,” Jennings said, paper whispering as he sorted.

Sebastian rallied, snatching at dignity. “Fine. The house, the accounts. Dad promised—”

“The residence at Larch Avenue,” Jennings read, “bequeathed to Mr. Sebastian Wells, subject to encumbrances.”

“Encumbrances?” Diane—stepmother since I was thirteen—repeated, pushing pearls back into place at her throat.

“The mortgage,” Jennings said. “Three hundred and eight thousand remaining. Additionally, a second lien from the equity line used in twenty twenty-one.”

Sebastian’s mouth made an O that tried to become an argument.

“The vintage Ford pickup,” Jennings continued, “to Mr. Wells.”

Diane’s smile returned. Trucks photograph well.

“And the antique doll collection,” he finished, turning a page, “to Miss Montgomery, along with all appraisals and provenance documentation.”

Sebastian snorted, relief cheap and loud. “See? She gets the creepy toys.”

“What’s the appraisal?” I asked, calm as a tape measure.

Jennings’ eyes crinkled. “Forty-seven dolls. Two from 1872. A complete early Madame Alexander set. Current valuation: five hundred and twelve thousand.”

The quiet had edges this time. Aunt Beatrice’s tissue stopped pretending to be useful. My cousin Jake dropped his coffee. No one picked it up.

Sebastian blinked like a man waking from a dream and falling off the bed. “Half a million… for dolls?”

“Antique dolls are serious investments,” Jennings said. “And your great-grandmother was, it appears, a visionary collector.”

Dad’s bedside words echoed. Not just sentiment. An asset, disguised as fragility, guarded in plain sight.

Sebastian puffed up for one more swing. “Ava can’t run a company. An MBA means—”

“From a program you finished in five years,” I said evenly, “with a two-point-eight because you took semesters off to find yourself.”

“Ava,” Diane snapped, “that’s no way—”

“You’re right,” I said, turning to Sebastian. “Mr. Wells, owner of nothing he’s maintained, beneficiary of liabilities, connoisseur of unearned certainty—thank you for your minimal contributions.”

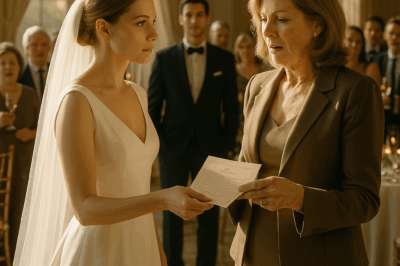

Jennings coughed into his hand to hide a smile. “There’s also a letter from your father to be read into the record.”

He slipped a single page from an envelope and began.

“Ava,” Dad had written, the scrawl he used when he refused to wear his glasses. “You’ll take heat for this. Let them cook. You know where the beams go. You know load-bearing from cosmetic. If you’re reading this, it means I didn’t get to tell you again: you built this. Keep it upright. As for your brother—if he ever decides to work, you know what to do. If he doesn’t, you still know what to do.”

Tears hit me without warning, honest and untheatrical, the way rain sometimes surprises you on a day the forecast promised sun.

Part III — The Foundation and the Facade

After the reading, the hallway outside Jennings’ office became a small theater of grievance.

“This isn’t fair,” Diane hissed, grabbing my elbow as if my ligaments were a dimmer switch she could use to soften the scene. “Your father wanted family unity.”

“He wanted solvency,” I said, removing her hand. “And he wanted payroll met.”

Sebastian lurched after me. “We need to talk.”

“You’ve had my number for a decade,” I said, turning. “You could have called any time to ask how the business worked. You chose not to.”

“You could’ve told me,” he shot back, voice warping toward boyish.

“I did,” I said softly. “In every meeting you skipped. In every email you ignored. In every crisis I handled so you wouldn’t have to put on a hard hat and learn which end of a level is useful.”

He flinched, then framed it as injury. “You’re shutting me out.”

“I’m honoring the boundary Dad set and the work I did.” I pressed the elevator button. “The business isn’t hiring.”

It was petty. It was also accurate.

Three weeks later, in the office I’d painted the color of new plans, I watched crews pour the slab for our first net-zero duplex. The owner and chief executive officer placard still surprised me, not because I hadn’t earned it, but because names on doors still felt like things other people received.

“Miss Montgomery?” my assistant said over the intercom. “Your brother’s here.”

Sebastian stood in the doorway with hunger in his face I’d never seen before. Pride had burned; ash remained.

“Nice office,” he said, eyes flicking over the framed photos of crews smiling in front of houses we’d turned from sketches to keys. “Green builds, huh.”

“Demand’s growing,” I said. “We’re meeting it.”

He swallowed. “I… need a job.”

An old ache tugged—memory of tag-team birthdays, of a boy who used to share his fries. I let the ache arrive. I didn’t let it drive.

“What can you do?” I asked. No malice. An honest question.

His mouth opened, then closed, then opened again. Words—strategy, leadership, networking—tried to audition for competence. None passed.

“We’re not hiring,” I said. “But here’s a list of union apprenticeships and a contact at a subcontractor who owes me a favor. Show up at 6 a.m. Wear boots. Bring humility.”

His eyes flashed, wounded animal and cornered prince layered into one expression. “Dad wanted me to lead.”

“Dad wanted it to survive,” I said, standing. “He chose accordingly.”

At the door he paused. “You won, Ava.”

“No,” I said. “I worked.”

He left. The elevator took him down to the ground floor, where crews who’d known me since I was nineteen were clocking in from lunch, laughing that regular laughter of people who do things with their hands and therefore know the shape of a day. He looked small near them. Not because he was small. Because he had never learned to lift.

Part IV — The House That Stands

Montgomery Builds turned a profit that year larger than any we’d posted in a decade. It wasn’t magic; it was maintenance. I tightened a bid process Sebastian didn’t know existed, swapped a flaky supplier for a hungry upstart, invested in training that cut injuries by 40 percent, and kept coffee on every site because the cheapest way to honor a crew is to make it easy for them to warm their hands when the river wind bites.

The dolls lived in climate-controlled glass in my living room like sentries, each with their little birth papers tucked behind their backs. On Sunday mornings I dusted them like my grandmother had taught me, cotton glove and a breath of patience. Each doll had a story; Dad believed in stories as much as specs. He’d told me how his grandmother bartered eggs for a wax-faced German beauty during the Depression. How my mother had found a rare French girl at an estate sale when they couldn’t afford anything else but bought it anyway and ate soup for a month. Not just sentiment. Continuity. The lesson glowed: you protect what will appreciate while others laugh at what they don’t understand.

Spring brought a letter from Jennings’ office. The mortgage on Larch Avenue was in arrears. Diane had moved in with her sister. The pickup had been sold to cover a few months. Sebastian had taken a job—not with my contact, but with a tech sales firm that liked the gleam of his suit and then quickly learned the cost of his polish.

“Ava,” he texted me one night I should’ve had my phone off. “Do you hate me?”

I thumbed a reply and then didn’t send it. Hate was never the thing. Exhaustion was. So was grief—for the brother he could have been if someone had asked more of him earlier than I was allowed to ask now.

At Dad’s grave on the anniversary of the day he insisted on installing cabinets himself in our first in-house renovation because “you can’t own a thing you don’t know how to build,” I sat on the grass and talked like I did when he ferried me home in the work truck at fifteen while Bruce Springsteen told us about highways and mistakes.

“I did what you asked,” I said. “I kept it upright.”

A robin hunted in the hedge. A backhoe groaned at a far-off site. It sounded like progress.

On Monday, while walking a client through framing, I got a call. “Inspection passed,” my superintendent said. “And the city council approved the rezoning change on Riverbend. We’re a go.”

We high-fived, the ridiculous kind that makes plans feel like celebrations.

On Friday, I visited the duplex. The first family had moved in already—two kids in socks sliding down the hall on LVP like it was hardwood in a castle. Their mother cried into my shoulder when she learned the utility bills would be half what she’d budgeted. “No one does this,” she said. “Not for us.”

“More will,” I said. “If we build it.”

Months blurred in the way good seasons do. Problems arrived and were solved. Crews argued and laughed and built. Loans were negotiated. Land was walked. I knew where every bit of stress lived in my body and how long it took to settle once a pour went right. My office plants stayed alive.

One night the buzzer rang at nine. Sebastian stood on the stoop with a six-pack of apology beer that cost more than it needed to. He looked older than last time. Different older than me. The kind that comes from kicking against what is instead of using it.

“I tried the apprenticeship,” he said. “I lasted a week.”

“I’m not surprised,” I said, and stepped outside so the dolls wouldn’t overhear. “What do you want, Bas?”

“To start over,” he said, not looking up.

“Start,” I said. “Over is a lie.”

We sat on the top step and split one beer because if I’d let him hand me the whole contrition, he’d think it absolved anything. We didn’t solve our childhoods. He didn’t suddenly become a man who wanted to be on site at dawn learning the feel of a nail gun. He didn’t ask for money. I didn’t offer any. He left with a contractor’s business card and a suggestion to show up Monday, sweep without complaint, and say please and thank you.

He texted a week later. “Made it four days. Blisters.” Then a picture: his palm, raw and proud. “Going back Monday.”

I did not reply with praise. I sent a thumbs-up. Progress is allergic to parades.

The day I had the new sign installed—Montgomery Builds in brushed steel over cedar, Dad’s old truck restored and parked out front like a mascot that refuses to retire—Jennings stopped by unannounced and stood with me in the parking lot smelling like rain.

“He’d be proud,” he said.

“He’d ask for a tour,” I said. “He’d ask about margins.”

“And then he’d make you eat,” Jennings smiled. “He didn’t like celebrations without food.”

We ordered pizza for the office and bites of something too fancy for the crews on site, which made everyone laugh, and ordered pizzas for them, too.

That night, I drove by Larch Avenue. Someone new lived there—a young couple who’d painted the porch a better color, who’d put up a swing and were arguing good-naturedly about curtain rods while a dog tried to eat a fern. The house looked like it had shaken off old expectations and settled into a life it could afford.

I didn’t hate Sebastian. I loved him the way you love the proof of a theorem: if A, then B. If entitlement, then collapse. If work, then growth. He was choosing which line he’d follow, one blister at a time.

My phone buzzed. A text from my foreman: “Tomorrow’s pour is at six. You coming?” I sent back, “Wouldn’t miss it.” He replied with a thumbs-up and a concrete emoji, which I found charming.

On my way home, I stopped at a light and reached over to the passenger seat where one of the dolls in her case rode shotgun on delivery to the appraiser for insurance updates. She stared with solemn painted eyes at the road ahead. Fragility can be a fortress when you understand its value. Asset, not sentiment. Investment, not prop.

At a red light I thought of something Dad said after a beam slipped and nobody got crushed because he’d insisted on redundancy. “We build so gravity has to argue with us.”

People had underestimated me because I let them, because it kept their gravity off my work while I laid foundation. My brother had mocked my inheritance because he didn’t know where the joists were. The lawyer had read a letter that sounded like grace stitched to instruction.

We get the stories we build. Some are façades. Some stand.

The next morning, I was on site with a clipboard and coffee, watching the first ribbon of gray pour into a trench that would be a wall that would be a house that would be a life. The crew joked. The pump groaned. The sun broke over the lattice of rebar. My boots were not clean. My heart was not either. Both were honest.

“Level,” I said, and the man at the screed grinned. “You got it, boss.”

“Owner,” my project manager corrected, tweaking me just to keep me human.

“Both,” I said, because I had earned the luxury of accuracy.

At lunch I went back to the office. A padded envelope waited on my chair—no return address, clumsy handwriting I recognized anyway. Inside, a single photo of me at seven, hair in crooked pigtails, a doll clutched like a question. On the back, Dad had scribbled long ago, Your hands can hold anything you build.

I propped it against the monitor where the budget spreadsheets lived. Then I went back to work.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I adopted my nephew after my sister died. Christmas came. My mother-in-law said, “Only real…

I adopted my nephew after my sister died. Christmas came. My mother-in-law said, “Only real grandchildren at dinner. Don’t bring…

CH2. I CAME HOME AFTER YEARS AWAY – AND FOUND DAD IN A HOSPITAL, ON LIFE SUPPORT. MOM AND MY SIBLINGS…

I came home after years away – and found Dad in a hospital, on life support. Mom and my siblings?…

CH2. Her boss secretly erased her raise — But she built the system that exposed every lie

Her boss secretly erased her raise — But she built the system that exposed every lie Part 1 The…

CH2. The Irony: ‘Leave!’ They Said, Unaware of My Ownership. The Moment I Revealed the Truth.

The Irony: ‘Leave!’ They Said, Unaware of My Ownership. The Moment I Revealed the Truth. Part 1 “I don’t…

CH2. You’re Being Selfish! Said My Son And His Wife Threw Wine At Me, So I Texted My Lawyer!

You’re Being Selfish! Said My Son And His Wife Threw Wine At Me, So I Texted My Lawyer! Part…

CH2. At My Wedding, Mom Smirked: “It’s Just a Car.” So I Handed Her the Legal Envelope…

At My Wedding, Mom Smirked: “It’s Just a Car.” So I Handed Her the Legal Envelope… Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load