When my mom texted, “We changed all the locks and the gate code. We no longer trust you,” I knew this wasn’t just family drama—it was betrayal disguised as love.

Part 1

At 8:14 a.m., my phone lit the dim apartment with that antiseptic blue that never feels like morning, only like exposure. The message was short enough to fit in the preview pane and long enough to collapse my chest: We changed all the locks on the front door and also the gate code. We no longer trust you.

I didn’t reread it. I didn’t need to. The words were scalpel-clean, no fat to grab, no phrasing to argue with. The woman who had once tapped my newborn nose with a finger and called me her greatest blessing had just evicted me from a life I’d financed, with the same nimbleness she used to reset the thermostat when I was a kid—quietly, decisively, in a way that made you wonder whether the sudden chill was your imagination.

I typed back: Noted. That was clever. But you forgot one thing.

I didn’t hit send right away. The dots blinked in the corner of the screen, as if my phone was breathing. In my head I reached for the script I’d used my whole life—the one with patient explanation, softened tone, timing that bent around other people’s convenience. It wasn’t there. There was only a waiting silence that felt like a blank stage, mid-spotlight.

Before I tell you what happened that morning, tell me where you’re listening from. It seems silly, inviting a faceless crowd into a story that made my jaw ache, but when harm is dressed as family, it’s easy to think you’re alone in the room. I wasn’t. You aren’t. This is the part where I say my name, like confession. I’m Taylor Robinette, thirty-one, a financial manager tucked into the steel ribs of Chicago. For four years, I’ve been paying almost five thousand a month for a house I do not live in. Mortgage, taxes, insurance, the internet bill so my father can watch baseball with the sound up and the closed captions on. Every single one auto-drafted from the account with my name at the top and an interest rate that burned like a fever.

My mother called it family teamwork, in that lacquered voice she uses with bank tellers and pastors and the cashier at the home improvement store. My father, Robert, sixty-two, called it “doing the right thing,” which in our house was a synonym for “doing the quiet thing.” My sister, Lindsay—three years older, two children, permanent chaos—called it my “superpower,” as if I’d been blessed at birth with a special gift for transferring money and shutting up about it.

No one actually asked. They hinted. They arranged. I was twenty-seven when I co-signed the mortgage. Everyone clapped in the kitchen. There was carrot cake from a grocery store bakery and a congratulatory speech that opened with “You’re such a blessing” and closed with “We’re so proud of our family trust.” Trust. I know now what they meant: the kind you exploit. The kind you cash.

My mother is Elizabeth, with a smile you can hear through the phone and a memory that catalogs favors in neat chronological order. She has a way of turning guilt into currency. She’ll ask about your day and then about the roof in the same breath, so that concern and cost become indistinguishable. “You know, honey, that roofer said the flashing is still bad. It’s just hard watching your father on that ladder.” Translation: send money. “We hate to bother you.” Translation: this is your job. “You’re keeping this family afloat.” Translation: you owe us the shore.

Lindsay is an artist of helplessness, a gold medalist in emergency. Her crises are fluently plural, and her apologies always arrive attached to a need. When her car breaks down, it’s “for the kids.” When her account overdrafts, it’s “just until Thursday.” She’ll text, “Can you spot me?” as if money is a stool she’s been standing on for years and not a floor I keep reinforcing.

Dad keeps the peace. Or whatever passes for peace when the cost is your daughter’s spine. He pecks at his phone with his index finger and sends mild thumbs-up emojis after I wire over rent. He calls mishandled debt a “system glitch.” Even when the bank flagged a credit inquiry last year—an application I never filed—he radioed in with a soothing story: a clerical mistake, nothing to see, these things happen.

I built spreadsheets to convince myself I was in control. Rows and rows of payments, color-coded, a slender fantasy that fury can be managed with a ledger. I labeled the biggest column temporary, as if naming a storm softens its wind. Temporary stretched like an elastic waistband until it fit their comfort. The house became theirs. The debt stayed mine.

The morning of the text, I tried to keep my routine intact, like a museum exhibit. Two slices of toast, one with jam. My morning run postponed for later. Coffee instead of tea because coffee feels like something you drink before battle. Outside, the city was a chorus of buses and impatient horns and a laugh from the alley that cracked like ice. Inside, my apartment was an archive of unopened mail and plants pretending not to notice how often I forgot to water them. I sat at the table with a mess of envelopes, each with my name angled in machine ink, and thought of my mother’s hands when I was nine: the way she would hold my chin to wipe my face, gentle and proprietary at once. Only later do you learn that some hands are less about care than containment.

People tell you betrayal feels hot, but the truth is colder. It’s a clarity that stings. It moves through you like a winter draft under a door, so clean it makes your eyes water. With that message, the weather inside me changed.

It didn’t start that morning, of course. It started with a post on Facebook two weeks before—banners of digital confetti around a photo on the front porch of the house I pay for. Lindsay stood in the middle, confident, chin lifted like she’d just won a scholarship. My mother was beaming with a little wooden sign that said, Home Sweet Home, the cursive looped like a lasso. The caption read: “So proud of our daughter for building a home we can all share.” I scrolled expecting to find my name somewhere in the hashtags, maybe hidden like a backstage hand. There was nothing but praise floating up like helium. “You raised such a strong daughter, Elizabeth!” “Lindsay, you’re the rock!” Heart emojis, house emojis, a little digital champagne bottle erupting pixels.

I was parked outside a grocery pickup lane, waiting for a teenager with a bin to appear and hand me my weekly order, when that caption sliced through the screen. I sat very still. I didn’t blink. I don’t know why stillness feels like protection when you’re blindsided. As if motion would crack the glass and you’d spill out of your own life.

Two days later, a woman from the bank called with a cheerful voice that did not match the words in her mouth. “Hi, Ms. Robinette. Just confirming a request to update the primary contact for your mortgage.” I put my pen down. “To who?” “A Ms. Lindsay Carson,” she said. “The documents are pending verification.” My apartment tilted by a degree. I said nothing, which is a new skill I have learned: the kind of nothing that makes room for facts.

That night, I found the missing money within minutes—a transfer to an old emergency card I’d once shared with Lindsay, a favor welded into a future shackle. “Did you use my card again?” I texted. She replied with the breezy defensiveness of someone certain you owe her softness: “Don’t make it a thing, Taye. The kids needed shoes.” My mother followed ten minutes later, the diplomat, policing tone not behavior. “Honey, Lindsay’s going through a rough patch. Let’s not start a war over a few dollars.” A few dollars. She’s the kind of person who uses plural to shrink a singular wound. “A few dollars” had built their porch, fixed their roof, kept the water from choking the basement. “A few dollars” was a solvent she poured over my boundaries to dissolve them into something that could be poured into her molds.

The next ding was the group chat, newly christened “family circle,” which felt like a joke about geometry made by people who only ever walked in straight lines to their own convenience. Someone sent a meme: a man handing over his wallet with the caption Big Sponsor Energy. My cousin tagged me with a laughing emoji. My father chimed in: “Keep the donor happy.” It is one thing for the people you love to be cruel in private. It is another to find out they have a language for you when you leave the room.

I left the chat. They added me back with a row of balloons like a kidnapper’s apology. I left again, and this time I blocked them all—the digital version of closing your eyes on purpose.

The next weekend I drove to the house, because muscle memory is stubborn, and there’s a lawn that grows whether or not a person is thanked for mowing it. The air smelled like gasoline and clipped stems, the same way it did when I was sixteen and Dad taught me to “follow the lines.” I paused by the kitchen window for water, and the glass traded the reflection of my face for the room beyond, where my mother and Lindsay stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the relaxed posture of people confident in their conspiracy.

“Did you see her face when Aunt Karen asked about the deed?” Lindsay’s voice was bright, almost teenage.

My mother’s answer arrived low and pleased: “It’s almost done. Once the paperwork clears, there’s nothing she can say. She’s the one who put her name on the loan. Her problem now.”

Lindsay snorted. “She’s always been a guest with a wallet.”

And then the sentence that scooped me out of myself and held up the hollow for examination: “She’s not family anymore,” my mother said. “She’s just a sponsor.”

The water bottle slid from my hand and rolled into the grass, a small domestic planet tilting away. I didn’t pick it up. I listened to birds. I listened to the neighbor’s dog. I listened to the clean sound of my mother’s certainty, and I let something inside calcify into a surface that could take weight.

That night I didn’t drink. I didn’t cry. I didn’t call anyone to translate pain into an anecdote you could tell at brunch. I sat at my desk with the blinds half-closed and made a different choice: I opened my banking app and my spreadsheet and every folder of emails I’d labeled in a fever of organization. The blue-white rectangle of my laptop carved a light across a scatter of envelopes. Mortgage. Insurance. Internet. Property taxes. Transferred to a roof, a water heater, a furnace that purred like a satisfied animal. Four years of help became $211,724, which is a number that looks like a gate.

Numbers don’t care how you feel. They just sit there, exact and indifferent. They won’t lie for you, and they won’t hug you either. I needed that kind of company. At 11:46 p.m., I canceled every automatic transfer, my index finger hovering for a second over each confirmation button like a priest’s hand before a blessing. The next payment was due on the fifteenth. Not this time.

I typed my mother the message I’d drafted in my head since the bank call: Noted. That was clever. But you forgot one thing. I sent it this time. I watched the little status bar confirm, as if the phone were nodding back.

Then I began what I called, out loud because naming matters, the audit.

I right-clicked on an audio file I didn’t remember recording and clicked play. I’d left the voice memo app running while mowing. The speakers exhaled the past into the present: the sentence about me being a sponsor, the little sisterly laugh that followed, the soft pleasure in my mother’s reply. I dragged the file into a new folder and renamed it kitchen truth, which is both on the nose and precisely the point.

Proof is a comfort for people like me. You can’t negotiate with a screenshot. A PDF does not answer a question with a sigh. I took pictures of everything. I printed stacks. The printer coughed into the night, spitting out white sheets that drifted into piles: payments, bills, messages. I taped the Facebook post to the wall. I taped the bank notice. I taped the group chat meme and my father’s little text about donors. My apartment began to look like the inside of my skull—a messy museum of all the moments I’d tried to pretend were smaller than they were.

Three days later, a thick white envelope slid under my door with the sound of a timid apology. Inside was an invitation printed on gold paper with a faux wax seal. “Please join us in celebrating Elizabeth Carson’s 60th birthday,” it read in the kind of script that makes you feel underdressed. Across the bottom, in cursive so pretty it could convince you the words were kind, a quote: A house is not a home without family.

I laughed out loud, an unfamiliar sound in my own mouth. I pinned the invitation to my fridge next to the spreadsheet printout. Two shrines. One to their fantasy. One to my reality. My refrigerator became a crude altar to the god of clarity.

I called my grandfather, William, the only person whose love has never arrived with a receipt. He picked up on the third ring with a throat-cleared “hello” that always sounds like permission to be honest. “They called me a sponsor,” I said, skipping pleasantries like a line you refuse to stand in anymore.

He exhaled through his nose. “Then it’s time they learn what happens when a sponsor stops sponsoring.”

This is why I call him. Not because he rescues—he doesn’t. But because he names things with the tenderness of a doctor telling you a diagnosis early enough that treatment still matters.

I spent the week in preparation. Not for a fight—fights are loud and sloppy and leave everyone looking tired. I prepared for precision, the way a surgeon washes their hands. I printed bank records. I labeled manila folders. I moved money to an account they didn’t know existed, the one with a name deliberately boring. I reorganized my email into a chronicle that you could hand to a stranger and say, Here, this is what happened. I boxed up childhood photographs from the house the next morning, while they were out. A baby in a sink bath. A Halloween costume with wings made from coat hangers. A school play where I was a tree and my mother clapped loudest. Nostalgia is a magician; it loves to pull a silk handkerchief over harm and say, Ta-da. I packed the photos and left the guilt.

I did not plan to speak at the party. I planned to be there, to be seen, a fault line under polished floors. I would let silence do its strange, honest work. Silence makes people loud. Silence shows you what’s in the room when your willing laugh isn’t stuffing the corners.

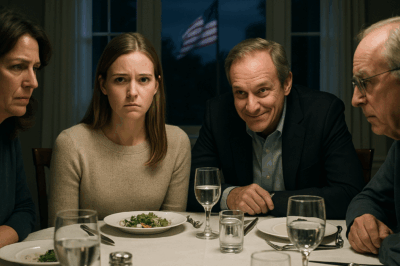

The night of the party, the Chicago sky had that dusky bruise of late summer—a heat that bordered on decadent even as the air hinted at rain. The banquet hall was dressed in gold and green, my mother’s colors, “royalty tones,” she’d say when she bought table runners and candles and the kind of charger plates that pretend to be plates but are just stage set. People wore their good shoes and their forced smiles. Waiters ferried champagne flutes like delicate decisions. There was a slideshow looping on a screen as big as a confession. Beaches. Birthdays. A Christmas photo with matching pajamas that itched; I remember the itch; it’s never shown in the picture.

I stood near the entrance, not hiding, not announcing. Lindsay was on stage holding a microphone with the posture of a woman who believes microphones are her birthright. “This home represents sacrifice and love,” she said. “We’ve all worked so hard to keep it.” I felt laughter rise in my throat like steam, and I pressed my tongue to the roof of my mouth the way my therapist taught me when I needed to redirect a reaction. Worked, she’d said. As if Venmo were a verb for penance.

I waited for the applause to break and drain. Then I walked forward and asked for the microphone in a voice so calm it surprised me. Not because I am brave; because I’m tired.

“I wasn’t planning to say anything,” I started. “But since we’re celebrating legacy, let’s talk about what it cost.”

Her smile stiffened. My mother leaned toward her cake like it might shield her. Dad’s jaw worked against a sentence he could not find. I raised a small USB drive, the object strangely theatrical for something so ordinary. “Could someone plug this in?”

Curiosity is a powerful ally. A cousin complied. The screen flickered. The audio began, faint at first, then clear enough to make the room inhale all at once: “She’s not family anymore. She’s just a sponsor.”

Gasps. A glass fell somewhere with a brittle clink. I didn’t look at my mother. I didn’t look at Lindsay. I watched the crowd listen to what truth sounds like without decorative language. Then the next slide: the group chat screenshot, the meme with the wallet, the caption that had become a family joke where I sat outside the punchline. “Here’s what family legacy looks like in our house,” I said, and then I put up my spreadsheet, the neat brutality of numbers bridging the gap between story and fact. Mortgage. Taxes. Repairs. Insurance. The total circled in red: 211,724.

“This,” I said, “is the cost of your legacy.”

My mother whispered, “You’re humiliating us,” the word us tumbling into a plural I no longer recognized myself inside.

“No,” I said. “I’m clarifying the math.”

Dad stood, the peacemaker trying on anger like a suit he hadn’t tailored. “You don’t do this to your mother,” he said. “Not on her birthday.”

“You used my credit score to take out a loan last year,” I replied. “I have that paperwork, too.” He sat back down on the quiet that followed, as if someone had removed the batteries from his argument.

Lindsay’s voice trembled. “It was family help. We agreed.”

“I don’t remember that agreement,” I said. “I was busy paying your bills.”

There’s a moment in every performance when the audience decides whether it’s a comedy or a tragedy. The room hadn’t decided yet. I let the silence work. It showed them what was there.

And then a voice from the back said, “Enough.” The room’s attention pivoted like a weather vane toward my grandfather, William, cane in hand, walking forward with a slow authority that made even the waiters step aside without looking like they had moved.

He took the microphone. He didn’t raise his voice. He pointed it at the people he’d raised. “You raised a thief,” he told my mother. He pointed at my father. “And a coward.” Then he turned to me, and his mouth softened in the way that always makes me relieved and grieving at once. “You were right,” he said. “I read your message. You were right to stand your ground.” He cleared his throat and continued with a sudden bureaucratic sharpness. “Last week I changed the trust. Lindsay’s name is gone. The property and family accounts are yours.”

The rest of the room reacted with the sound of a hundred tiny decisions—the calculations in eyeballs, the whispered texts drafted in pockets, the old alliances tugging their hems as if they could be tailored, mid-party, into something else.

“You can’t do that,” Lindsay said, and sounded less like a woman than a child tugging at a curtain that would not move.

“Legacy isn’t a birthright,” my grandfather said. “It’s behavior repeated.” He gave the microphone back to me like a baton in a relay he trusted me to finish.

I didn’t make a speech. I said one thing: “You changed the locks,” I told my mother, the words landing with the exact weight of her text. “But I changed the keys.”

I put the stack of invoices on the gift table among the wrapped boxes and ribbon curls. I walked toward the exit. Not a single person tried to stop me. Doors can be dramatic; these were polite. They closed behind me with a whisper that sounded like something I had been waiting to hear for years: not goodbye, not good riddance—just the hush of a room that no longer had a claim to my steps.

Outside, the river held the city’s lights and shook them into smaller brightnesses. The air was cool against my wrists where my veins pulsed like I’d been running. I was not running. I was walking, steady. I pulled my blazer tighter, feeling the lining slide over my shoulders, and at last, I exhaled in a way that was not a preparation for the next thing I owed.

Seventy-two hours later, my laptop chimed with a sound that will forever be different to me. Incoming wire transfer: $211,724. No apology in the memo line. No sender name spelled out with the grandmotherly flourish my mother adds to cards. Just numbers, clean and cold and unmistakable. I watched them settle in the account like ballast. Then I closed the laptop and let silence fill the room, and for once it wasn’t a demand. It was a gift I could keep.

I brewed tea. I sat with it while it steamed the air, something softer than coffee, something without war in it. No messages buzzed. No jokes about donors popped up on my phone. Peace doesn’t announce itself. It arrives in the negative space where a need used to be. It shows you that the ache you called love was actually a bruise you stopped touching.

Their lawyer emailed a form sentence with a PDF attached. I replied with a line that fit wholly in the subject line: Transaction received. No further contact necessary. Then I slid the email into the trash as if it had always belonged there.

Later that week I drove to my grandfather’s house, a place where the rugs are worn down by actual life and not by staging, where the kitchen table looks like a kitchen table and not a catalog. He sat on the porch with a cup of tea and a light in his eyes that made me want to cry even though nothing hurt right then. “They paid,” I said.

He nodded like he’d already marked it down in a ledger that held bigger truths. “Guilt always pays late,” he said. “But it pays.”

We sat for a while with no need to make words do anything other than be accurate. Then he said, “Forgiveness requires accountability, Taylor. They haven’t earned it.”

“I know,” I said. “Peace doesn’t need their permission.”

“Now you sound like someone who understands the cost of freedom,” he said, and what used to sound like a platitude felt suddenly like a balance sheet—numbers equaling numbers, a clean line under them to show the work was done.

The sun slid across the porch and turned everything gold in a way that looked nothing like my mother’s decorations and everything like a day doing its job. I drove home with the windows down. I passed the neighborhood with the house and did not turn in.

They changed the locks. It was the first thing they’d done for me in years.

They changed the locks. I changed my life.

The silence between us didn’t ache anymore. It felt like a scraped plate, clean. I had always believed belonging could be earned, paid down like a debt. But love doesn’t invoice. It answers. It meets you. It folds its legs beside you on a porch and lets you be more than what you provide.

If you’ve drawn your line and been told you’re cruel for it, I’m telling you: I see you. There’s a ledger somewhere with truth in two columns, and you are not in the red. Peace isn’t given. It’s chosen, sometimes with a trembling hand. And then it settles, and the tremble stops.

Part 2

The transfer hit my account like a door clicking shut, but money is only one of the locks you change when you leave a life. The next morning I made coffee for the last time out of habit and then remembered tea had been yesterday’s first free choice. I poured the coffee down the sink. The smell climbed the air anyway, stubborn and pleasant. I let it be. Not every remnant is an enemy.

Practicality is my native language. I opened my laptop and built a checklist. Call the bank. Freeze the credit. Pull the full report. Add fraud alerts. Change every password that had ever passed through a parental device or a shared network. Close the emergency card that had become a siphon. Open a file named next and filled it with verbs. Replace. Remove. Reclaim. I scheduled a consult with an attorney whose reviews sounded like relief made human: Nisha Patel, property and estate, plain spoken.

At work, my manager, Miriam, knocked on the edge of my cubicle like a person asking permission to be kind. “You’ve looked like a spreadsheet someone forgot to save,” she said. I surprised us both by laughing.

“I’m going to take some PTO,” I told her, letting the letters stand between us like a small fence.

“Good,” she said. “Take it. We’ll manage. You don’t have to make yourself smaller to fit our calendar.”

I wrote the out-of-office message like a dare to myself: I’ll be unavailable and not apologizing. For urgent matters, call someone else. I closed the laptop without the usual flinch.

Ms. Patel’s office smelled faintly of eucalyptus and printer toner. She shook my hand and met my eyes in a way that made me feel like a client and a person at the same time. “Tell me what you want, not just what you endured,” she said, and I almost cried because endured had been my whole personality for four years.

“I want the title clear and mine,” I said. “I want the accounts separated like arteries. I want a written agreement for their exit. And I want to do as little harm as possible while doing no harm to myself.”

She nodded. “We can work with that. Your grandfather’s trust amendment is clean.” She slid a copy across the desk. “We’ll file the deed transfer. We’ll draft a 60-day occupancy agreement with market rent—waivable if you choose—plus utilities, plus a clause that they acknowledge full repayment and release of claims.”

“I’ll waive the rent,” I said, quickly, then slower, like testing a sore tooth. “But not the utilities. Not anymore.”

“Good boundary,” she said in that neutral, steady tone lawyers use when they’re trying not to lean on your decisions. “We’ll also give them the option to buy you out with approved financing, if they can secure it on their own merit.”

“They can’t,” I said and didn’t feel cruel saying it. Accuracy is not cruelty. It’s oxygen.

She folded her hands. “Then set a date and stick to it. Clarity is kindness.”

We scheduled the locksmith for Friday morning. It felt theatrical, the symmetry of it: they had changed the locks; now I would. Only this time, the act would be accompanied by paperwork that didn’t hide knives in the subtext. I hired a realtor, a woman named Grace who had a calm voice even while navigating Chicago’s particularly theatrical brand of market nonsense. “We’ll stage it lightly,” she said. “No lies, just light. People buy the feeling of a clear decision.”

The night before we went, I walked my apartment the way you walk a garden before a storm, touching things that would be fine no matter the weather. The lamp my grandfather made when he was twenty. The framed print I’d bought with my first bonus and never told anyone the price of because I wanted one thing in my life that had nothing to do with thrift. The plants, stubbornly alive. I wrote a letter to myself and left it on the table: You don’t have to flinch. Flinching is not a reflex you owe anyone.

Friday came dressed like a day that wanted to behave. The sky was an obedient blue. The locksmith arrived on time, a woman in a denim jacket who looked at the house like it was a patient to be stabilized. Grace parked behind me and walked up with a clipboard and a kind of purposeful quiet that made me grateful for all the women who choose non-dramatic competence as their weapon.

My mother opened the door before I could knock. Her face had the unnatural smoothness of someone who’d practiced it in a mirror. “Taylor,” she said, as if the word contained both my birth and her disappointment. “What are you doing?”

I lifted the envelope Ms. Patel prepared, thick with copies. “Serving notice, changing locks, setting a clock.”

“You can’t just—” My father’s voice arrived from the hallway, wobbling between authority and apology. He stopped when he saw Grace and the locksmith as if their presence made this official in a way my presence never had.

“I can,” I said. “And I am. Sixty days. Utilities transferred by Monday. After that, we can discuss the listing.”

“Listing?” Lindsay’s voice floated from the kitchen, and then she was there, one hip cocked against the doorway like a defense. “You’re selling our home?”

“It isn’t your home,” I said, simply. “And we both know you prefer public stories to private facts.”

“This is cruelty,” my mother whispered, and there was a trembling to it that might have wrecked me a year ago. “After everything we’ve done for you.”

Grace stepped in the way a good witness does when a scene needs an audience with a pulse. “Mrs. Carson, the documents outline your options,” she said gently. “Today is just logistics.”

“Logistics,” my father echoed like it was a curse. “Your mother paid for your braces.”

“And I paid for the roof, the taxes, the last four Christmases, and the privilege of being discussed like a bank account with feet,” I replied. “This isn’t a ledger war, Dad. It’s a boundary.”

The locksmith cleared her throat in a small apology that contained an entire universe of I don’t want to be in your family drama. “I’ll start with the back door,” she said. I nodded. She disappeared down the hall with the soft jangle of tools.

Grace went to photograph the living room. The house smelled like lemon cleaner and something older underneath—dust and dinners and the damp that creeps in when people mistake habit for care. I walked to my old bedroom because I wanted to know if the space would recognize me. The poster I’d loved as a teenager was gone, replaced by a framed print of lavender fields that looked like a waiting room. My bookshelf was half-empty, my trophies stored in a bin under the bed that someone had labeled TAYLOR—MISC with a marker running out of ink.

There was a box on the top shelf of the closet I didn’t remember, my name written in my mother’s looping hand. Inside: a lock of baby hair, a hospital bracelet so small it looked like a doll’s, a note folded into a triangle. I unfolded it with the suspicion of someone who has learned that paper can cut.

My darling girl, it read, in the handwriting my mother used before her phone became her second voice. You are my greatest blessing. I promise to protect you always.

I sat on the bed that used to know the shape of my body and held the note like a bone dug up from a yard you used to play in. Maybe she had meant it then. Maybe love had been pure for a minute before fear turned it into a debt collection agency. Maybe promise and possession had been synonyms in her dictionary since she was a child. Understanding is not the same as forgiveness, but it is a kind of peace that doesn’t ask you to forget.

I put the note back in the box and the box in my bag. Some relics you keep not to romanticize the past but to mark the site of excavation: here is where I found the language that tried to keep me.

In the kitchen, Lindsay leaned against the counter playing with her phone. “You really going to toss your parents out like trash?” she said, casual cruelty, a flicked ash.

“Sixty days,” I said. “Options listed on page three.”

She rolled her eyes with such commitment it looked like an exercise routine. “Grandpa’s lost it,” she muttered. “He let you manipulate him.”

“You were in the room,” I said. “He didn’t look manipulated.”

“He’ll change it back,” she said and even she didn’t sound like she believed it.

My mother opened the refrigerator and then closed it without taking anything out, the visual equivalent of a sigh. “You don’t know what family is,” she said, and it hurt less than I expected. It sounded like a line from a play that didn’t suit her voice anymore.

“I know exactly what family is,” I said. “I just no longer agree to your terms.”

Grace called me from the living room. “I’ll need the utilities info,” she said, and I handed her the list I’d already prepared because I am myself even when I’m exhausted. We walked through rooms with the kind of attention that is half grief, half appraisal: the dent in the hallway from a year we moved a couch; the scuffed baseboard behind the console table no one dusted; the place on the stair rail where my palm still remembered the varnish.

The locksmith returned with a new ring of keys and the small satisfied smile people get when a job is done and the mechanism obeyed. “Back, side, and garage,” she said. “Front next.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it with a depth that surprised me. This woman had put a physical barrier between me and what hurt me, and it felt like a benediction.

My father followed me out to the porch as if the air might be more charitable out there. “You don’t have to sell it, you know,” he said, not looking at me. “We could work something out.”

“We had four years to work something out,” I said. “You made jokes about donors.”

He flinched. “I didn’t mean—”

“You did,” I said, but softer. “It’s okay to admit it. It’s not okay to keep doing it.”

“I wanted peace,” he said.

“You wanted quiet,” I corrected. “Peace is costly. Quiet is cheap. You bought quiet with me.”

He rubbed his jaw the way he does when he’s solving the wrong problem. “It’s your mother,” he said, which is the sentence he has always believed is both explanation and absolution.

“She’s an adult,” I said. “So are you.”

He looked old for the first time, not in the way of numbers but in the way of a person who has run out of story. “What do I even say?” he asked.

“Try ‘I’m sorry,’” I said. “And mean it without a request attached. Try it in a mirror first so you don’t harm anyone if you fail.”

He nodded like a student taking down notes for a test he hadn’t known was scheduled.

On the drive back to my apartment, I called my grandfather. He picked up on the first ring as if he’d been sitting with the phone in his hand, waiting to hear if the plane had landed. “How’d it go?” he asked.

“Calm,” I said. “Visible. Precise.”

He hummed, satisfied. “Your grandmother—God rest her—used to say: ‘Clarity will hurt everyone who profits from confusion.’ You owe them clarity, not comfort.”

“I found a note from Mom,” I said. “From when I was a baby. ‘I promise to protect you always.’”

“She meant it,” he said. “Right up until the day her fear started calling itself love.”

“What was she afraid of?” I asked, and I didn’t know if I wanted the answer.

“Losing control,” he said. “She mistook control for safety. Many do. I did, once.”

“You?” It startled me. He has always seemed like a person born knowing the difference between anchor and shackle.

“My brother,” he said, somewhere a smile in his voice but not in a happy way. “He owed me money for years. I called it ‘help,’ as if the word could mop up the mess. One day your grandmother put a ledger in front of me and said, ‘You can be his brother or his banker, not both.’ I picked brother, which meant I stopped being the bank. We didn’t speak for six months. Then we spoke like men, not transactions. He never paid me back. He gave me back my brother instead. You might not get that exchange. But you will get yourself.”

“I’ll take myself,” I said. The line went quiet in that companionable way I am learning is the best kind.

The next days were unglamorous, which is a relief when your life has been too dramatic without ever being cinematic. I watched a lot of hold music turn into humans. I waited for signatures. I filed letters. I took a hammer to a blind in my apartment that had annoyed me for months and replaced it with curtains I could open with one hand. The domestic victory felt disproportionate to the fabric involved. I allowed myself to be proud anyway.

Lindsay texted on the fourth day—not the soft apology Ms. Patel might have preferred as exhibit A in the case for reconciliation, but a tight little cluster of words: Can we talk.

We can, I wrote. But not about feelings until we agree on facts.

Facts? she replied, as if the word itself were an accusation.

You used my card without permission, I wrote. You tried to change the mortgage contact. You participated in mocking me in a group chat. You benefited from my payments and called them ours. You told people you built a home you didn’t finance. Those are facts. We can talk after you acknowledge them in writing.

She sent the typing dots a few times like a heartbeat that couldn’t decide whether to continue. Then: I didn’t mean to hurt you. We were scared.

Want to try again? I sent. Use I did, not we were.

Silence. Then: I used your card without permission. I tried to change the contact. I mocked you. I took your help for granted. I lied.

I breathed. That was more than I expected and less than it needed to be. Thank you, I wrote. Next step is concrete. Budget plan with a counselor, not Mom. Repay the last transfer from your account this week. Therapy with someone not recommended by friends. No contact for a month while we establish the new shape of our lives.

She waited seven minutes to reply. Fine. But you don’t get to act like you’re perfect.

I’m not perfect, I wrote. I’m just done. There’s a difference.

I didn’t tell Ms. Patel about the text; it wasn’t evidence. It was a weather report.

Word leaked to the family in that magic way it always does, via a cousin whose hobby is carrying buckets of information back and forth between houses and calling it love. Facebook tried to nominate itself as the narrator. I declined to participate. Grace put together the listing packet with photos washed in honest light. The house looked like itself for the first time in years—no caption, no false crown, just a building with bones and a price.

On a Tuesday that felt like any other, we planted a For Sale sign in the yard. My mother watched from the window, face expressionless, which for her is the same as a scream. I stood on the sidewalk and tried to feel victory and instead felt nothing, which turned out to be its own kind of win.

“Offers will come fast,” Grace said. “It’s a good block. The porch is charming. People love charming.”

I ran my hand over the wooden post as if it were the neck of an animal I was reassuring. Charming is a word that has too often excused bad behavior. I was learning to like it again, applied to objects.

Inside, Dad signed the occupancy agreement with a pen he held too tightly. Mom signed with a flourish. Lindsay printed her name with angry neatness. I initialed each page. The paper made small whispers as we turned it, like secrets deciding whether to leave.

When the utilities transferred, the first bill went to them like a small, unglamorous messenger. Mom texted: The gas is outrageous. I didn’t answer. She followed with: This is just vindictive. I sent back the meter reading photo and the rate chart. It is what it is, I wrote, and stared at the sentence, surprised that it didn’t sound like surrender. It sounded like weather.

That weekend I walked through the house alone, by agreement. I took a box from the attic with the smell of insulation clinging to the flaps. Photographs the size of my hand with edges soft from handling. A recipe card in my grandmother’s hand for a cake we never made right. I found the dent in the hallway and pressed my thumb into it like I could push back time. I thanked it, quietly, for existing. The past is not a place to live, but it does make a decent museum if you keep your hands off the exhibits.

On my way out, my mother was standing by the front door. “You’re really going to sell it,” she said, not a question and not an acceptance.

“Yes,” I said.

“Where will we go?” she asked, and for a moment I saw the woman who wrote the note to the baby, not the one who cataloged favors like jewelry. Fear, naked, looks like honesty.

“You have options,” I said, and I meant it. “Apartments close to the kids’ school. A smaller house you can afford. A rental for a year while you learn how to live inside a budget. Ask for help that isn’t me.”

“You don’t have to be cruel,” she said again, softer this time.

“I am not being cruel,” I said, and I believed myself. “I am being clear. I love you enough to stop helping you harm me.”

She swallowed, hard, the movement a stubborn climb. “You were my blessing,” she said, an old line pulled out of an old trunk, smelling of mothballs.

“I was,” I said. “I still am. Just not like this.”

On the porch, the air felt like a pause. The For Sale sign clacked softly in a wind that lifted and relented, lifted and relented. I closed the door behind me and felt the weight of it in my palm. Maybe I had been practicing for this all my life: learning the exact pull needed to make something shut without slamming.

Back at my apartment, there was a message from Ms. Patel with a single line: Clean title recorded. It felt like a certificate of vaccination. I forwarded the email to my grandfather with no note. He replied with a thumbs up emoji and a photograph of his porch at sunset, the railing catching light like a promise that kept itself.

That night I took all the papers off my wall. The Facebook printout. The meme. The bank notice. The spreadsheet total. I slid them into a box and wrote archive on the top in block letters. I pushed the box under the bed. I could have burned it, but fire is dramatic, and I am done with drama that doesn’t build anything.

The first offer arrived on Wednesday, then a second on Thursday, both above asking. “We can set a deadline for best and final,” Grace said, efficient joy in her voice.

“Set it,” I said. “Sunday at five.” The date landed like a punctuation mark. A last period at the end of a sentence that had gone on too long.

On Saturday morning, I made tea and wrote a letter to the house that I would not mail because you can’t mail a letter to a building, and even if you could, I don’t think the post office forwards to places that exist mostly in your memory. Thank you for sheltering the girl who thought she had to earn every good thing, I wrote. Thank you for teaching the woman she doesn’t. Thank you for the creak on the second stair that will live in my bones longer than any bill. I set the letter on my table and let it be ridiculous and true.

Lindsay texted again that afternoon, a picture of her kids drawing on the driveway with chalk. The younger one had a bright green streak across his cheek, accidental war paint. The caption said: They miss you.

I stared at the picture for a full minute, long enough for my tea to go from hot to drinkable. I typed and deleted three sentences. Then I wrote: I miss them, too. When the house sells and the month is past, let’s plan something at the park. Bring no requests. I’ll bring ice cream.

She typed: Okay. Then: Thanks. Then, after a while: I’m trying.

Trying is not doing, but it is not nothing.

Sunday came in quietly. I ran along the lake and let my legs do the math my brain was tired of. The air tasted like water. The city opened itself the way a person opens their hands when they’re ready to stop grasping. At five, Grace called. “We have six offers,” she said. “Two are cash. One wrote a letter about raising their kids on the porch with the dented rail. I know you don’t have to care about letters, but I think you might.”

“I do,” I said. “Send me the numbers.”

We chose the second-highest offer because of the letter, which feels like a contradiction I can live with. Money pays the bank. Letters pay the invisible debt to the parts of yourself that still want a story to be more than math.

When we accepted, the digital signature confetti exploded on my screen—some platform designer’s idea of joy. I laughed, because it felt like being congratulated by a cartoon for doing something that had cost me sleep and history. Then I laughed again because maybe joy doesn’t always have to be solemn to be real.

I texted my grandfather: We’re under contract.

He sent back: Proud of you. Dinner this week?

Yes, I wrote. I’ll bring dessert.

Bring yourself, he wrote. That’s dessert enough.

That night, after all the numbers and calls and logistics had been tucked into their places, I sat on my floor and opened the box from my childhood room. I took out the note my mother wrote to the newborn and laid it beside the photo of me crying in a sink. I placed my own letter to the house beside them. Three artifacts from three eras of love—one unconditional promise, one constructed shelter, one honest goodbye.

I didn’t know what comes after selling a house that almost sold you. But I knew what came next: closings, keys, a calendar that no longer had an invisible bill due every day. I could see the shape of my life beyond their gate code. It looked like mornings I didn’t owe to anyone, evenings that belonged to the person I was becoming, and a number in my bank account that finally meant safety instead of silence.

I turned off the lights and went to bed early. On the nightstand, my phone lay face down. It did not buzz. In the darkness, my body remembered how to be a place I live and not a wallet other people sleep inside. I listened to the low, steady sounds of my own apartment—the refrigerator clicking itself awake, the pipes politely announcing water—and felt a thin seam of gratitude stitch me to the present.

There would be a closing. There would be an empty house. There would be the moment the keys left my hand for the last time. And there would be whatever came after, not a cliff but a path, maybe, with room to walk without checking who followed. I slept like a person who had paid her bill and kept the receipt.

Part 3

Closings are ceremonies for paperwork. No choir, no vows, just signatures that behave like sentences—subject, verb, consequence. Still, there are rituals you don’t expect. The bowl of peppermints on the conference table like a consolation prize for adulthood. The stack of manila folders lined with sticky flags in optimistic colors. The pen that feels heavier than it should, as if the ink were carrying the weight of all the bad stories you’re finally rewriting.

The morning of our closing, the sky was a gray so even it looked ironed. Grace met me at the title company with a smile that knew how to stay inside the lines. “You look ready,” she said, and I realized I was. Ready isn’t a mood; it’s a decision you’ve already made.

The buyers arrived—a couple with two kids orbiting their legs like moons. The little girl wore rain boots decorated with clouds, the little boy carried a stuffed dinosaur by its tail like a flag surrendered after a long war. The parents’ faces glowed with the particular mix of terror and desire that only real estate can inspire. We shook hands. Their names were Miguel and Harper. He smelled faintly of sawdust, she of citrus. Their letter had mentioned the dent in the hallway and the creak in the second stair; they had asked if the porch had enough morning light to raise tomatoes. Yes, I had thought when I read it. Yes to all of it.

Ms. Patel sat opposite me, crisp and precise, with an energy like a metronome. She murmured her reminders: scan, sign, initial, pause. Some documents are reassurances disguised as forms: the clean title, the trust amendment recorded, the occupancy terms fulfilled. Some are merely punctuation. The buyers signed in the tender hurry of people trying to make their joy behave. I signed in the steady cadence of someone leaving on purpose.

Halfway through, the door opened. My father stepped in wearing the same shirt he wore to job interviews when I was a kid, a blue that always looked like a question on him. He stood by the door as if the floor might punish him for going any farther.

“May I?” he asked the room, not me.

Ms. Patel looked at me. I nodded. Permission is a key I now hold.

He took the chair at the far end, outside the theatre of signatures, hands folded like he was learning to pray. For five minutes he said nothing. Then, while we waited for the notary to stamp a small, officious seal, he cleared his throat.

“I’m sorry,” he said. It came out imperfect and human, without the scaffolding of a defense. “I am sorry that I let quiet pretend to be peace. I am sorry I joked about donors. I am sorry I did not defend my daughter when she needed a father instead of a referee.”

I looked at him, really looked, and I saw the man who used to untangle my necklace chains with a needle by the kitchen window, patient and intent, unraveling knots I had made with the thoughtless enthusiasm of a child. I nodded. “Thank you,” I said. I didn’t hug him. Some bridges need to be inspected before you walk on them.

Harper, the buyer, smiled at me like a friend who knows better than to intrude on a private weather pattern. “We’ll take care of the porch,” she said later, quiet, as if the house could hear.

“I know you will,” I said. “The tomatoes will be happy.”

The last page arrived. Signatures multiplied. There was a moment where everyone checked the math. When the escrow agent finally said, “Congratulations,” the word fell into the room with a soft thud, like a loaf of bread done baking. Useful. Nourishing. Ordinary.

We exchanged small gifts: I handed them a folder of house tips—trash days, the trick to opening the sticky bathroom window, the plumber who doesn’t lie. They handed me a card with a painted front door on the cover; inside was a note that made my eyes sting: Thank you for leaving a house we can be honest in.

Outside, the couple’s kids hopped in puddles, the dinosaur getting a bath in rainwater. I watched them for a moment, not as a woman who had been bled by a family, but as a person who had chosen a different ending. “Good luck,” I called.

“Good life,” Harper corrected with a grin. “Luck feels passive.”

“Good life,” I echoed back, liking the way the words fit.

When I got home, I set the new keys on my counter—the keys to my apartment, which suddenly felt like a destination rather than a waiting room. I poured tea and let the steam kiss my face like a job well done. My phone buzzed with a message from Ms. Patel: Funds wired. File closed. She added a small sun emoji, which from her felt like confetti.

I texted my grandfather: It’s done.

He sent a single sentence: Come over; I made stew.

His house smelled like rosemary and memory. We ate with spoons that had belonged to his mother, the silver worn smooth by other mouths, other winters. “How do you feel?” he asked, which is a question that sometimes means, What do you think? This time he meant feel.

“Like I put down a heavy box I didn’t know I was still carrying,” I said. “And like I might miss the box, just a little, because I got strong lifting it.”

He nodded like a man who had once put down his own box and discovered his hands did not know what to do for a while. “That’s the trick of burden,” he said. “It convinces you your strength belongs to it.”

“Do you think I was cruel?” I asked. The question surprised me, as if some small, stubborn judge in my chest had waited for the safe moment to show up and request a hearing.

“No,” he said, and took a sip of stew as if to underline it. “Cruelty requires enjoyment. You did not enjoy this.”

“I enjoyed the precision,” I admitted.

“So does a surgeon,” he said. “Precision saves lives.”

We watched the late light turn the room a softer color. He told me a story about my grandmother I hadn’t heard: how she once told a pastor that forgiveness was not a coupon but a contract—invalid until the other party signed. “She loved strong and straight,” he said, and I realized that some inheritances don’t need a lawyer.

On the third day after closing, I started therapy again. I had ghosted my last therapist the way people ghost good habits—unintentionally, then with shame, then with excuses that sounded like busyness. This time I chose a woman named Joy who didn’t giggle when I asked if the name was prophetic. “Sometimes,” she said. “Most days, it’s aspirational.”

In the first session, I itemized my story like evidence on a table. Joy listened without writing. “What do you want help with now that the emergency is over?” she asked.

“Not building new emergencies,” I said. “Learning the difference between generosity and self-erasure. Figuring out how to love people who behave badly without volunteering to be their punching bag. Also, sleeping without mentally balancing a thousand lines of debt.”

“That’s four separate goals,” she said. “We can take them in order or in parallel. Either way, expect boredom.”

“Boredom?”

“Health is boring,” she said. “It’s also where the good stuff lives.”

I laughed, and a knot in my chest loosened by a notch.

The utilities saga at the house became a Greek chorus for a week, tiny tragedies sent via text: The gas bill is obscene! The water company is ridiculous! Why is the internet this expensive? Each message from my mother was a distress call sent from a ship she’d assumed I would always row. I answered with facts only: rates, contact numbers, a screenshot of a budget template. At the end of each exchange, I wrote the same line: You can do this. It was the truth. I don’t know if she believed it. I was practicing believing people can be better than their worst habits, including me.

Lindsay sent proof-of-payment for the transfer she owed me—tiny, precise, almost petulant. She followed it with a selfie of her and the kids on a bus. “We’re practicing public transit,” she wrote. “Mom says it’s dangerous. The kids like the novelty.”

Proud of you, I typed, and meant it. She responded with a sticker of a sloth giving a thumbs-up, which felt like an honest mascot for slow change.

At work, Miriam pulled me into a small conference room with a window that looked out on a concrete wall painted with a mural of a lake that tried its best. “You’ve been different,” she said, not unkindly. “In a good way. You’re not volunteering for everyone else’s emergencies. Your numbers are tighter. Your meetings are shorter.”

“I stopped treating my job like a scavenger hunt for approval,” I said. “Turns out we already have a bonus structure.”

“We do,” she said, amused. “And you might be surprised to learn it isn’t optimized for martyrdom.”

She offered me a project I actually wanted rather than one I thought I should take to prove my capacity. I said yes. It felt like trying on a coat that fit without tailoring.

One night, Joy asked me to write two letters: one to my mother, the other to the part of me that had believed love was debt. “You won’t send either,” she said. “They’re for your nervous system, not the postal service.”

I wrote the letter to my mother in present tense because I wanted my body to feel the verb. I told her where the lines now were. I told her what I would and wouldn’t do. I told her that I knew fear had been her compass, that control had been her boat, and that I was not responsible for her learning to swim. I told her that the baby she had promised to protect had grown up and taken over the job. Then I wrote to the girl who collected receipts as if they were proofs of worth. I told her she could stop counting. I told her she had already arrived.

I slept like a person who had turned off a machine that had been humming in the background of her life for years.

A week later, my father asked to meet at a diner near the old neighborhood, the kind where the menu is laminated and the pie rotates in a glass case like a slow planet. He ordered coffee and wore contrition like a new jacket—visible, a little stiff.

“I started counseling,” he said, holding his mug with both hands like a man holding a steering wheel for the first time in a long time. “A men’s group through the union. We talk about the difference between peacekeeping and peacemaking. I have been the first, not the second.”

“How is it?” I asked.

“Uncomfortable,” he said, which I took as evidence of its usefulness. “The leader asked me who benefits when I stay quiet. It was not you.”

“No,” I said. “It wasn’t.”

“I told your mother she needs her own counselor if she wants me to come back to our conversations,” he said, and I heard steel in a place where there had only been tin. “I told her I won’t stand in the middle anymore. Let the heat be felt where it belongs.”

“Thank you,” I said, not for me but for himself. He nodded, and his eyes glistened without spilling. We didn’t hug when we left. We split the check. Splitting the check felt like a sacrament.

The house closed. The money landed. My account balance looked like safety without the caveat of shame. I moved a piece of it to a savings account I named porchlight, because I like naming things after what I want them to do. I moved another piece to a fund labeled generous, because I was not going to let fear turn me stingy. I can be kind without being exploited. Those are not mutually exclusive continents; they are a map, if you draw it right.

On a Saturday morning that stretched out like a cat in the sun, I took the train to a neighborhood I loved and toured an art class I’d been meaning to join for three years. “Beginner watercolor,” the flyer said, and I snorted at the moment of pure, unmarketable joy I felt just reading it. I signed up on the spot, bought cheap brushes that promised nothing, and spent two hours making colors act like grace on paper. The teacher, a woman with a gray braid and paint on her forearms, looked over my shoulder and said, “You’re letting the water do its job.” I smiled like a person who had finally learned the difference between force and flow.

Lindsay called the next afternoon, and I answered because our one-month pause had ended. “The kids want to see you,” she said. “They have drawings.”

“I have ice cream,” I said, and we met at the park with the cheap metal slide that shocks your thighs if you’re careless. The kids ran to me like joy had a collision speed. We ate drippy cones and compared dinosaur roars. Lindsay watched me with an expression tilted between gratitude and fear. “I’m going to the budget class,” she said finally, like a confession. “I don’t want to be this person anymore.”

“You were never only this person,” I said. “But I’m glad you’re practicing being a different one.”

She nodded. We didn’t talk about the house. We didn’t talk about locks. We talked about the younger one’s obsession with garbage trucks and the older one’s plan to build a city made entirely of slides. When they left, the little one wrapped his sticky arms around my legs and said, “Auntie Tay, come see my city when it’s done.” I promised I would, because that is a promise I can keep.

Two months after the closing, my mother texted me a photo of a small apartment with a balcony barely big enough for a chair. The caption said: Not much, but it’s ours. Then: I’m learning the bus routes. Then: I made a budget.

I stared at the screen long enough to taste the bitterness that still lived in my mouth. Then I typed: I’m glad you’re safe. The balcony will be perfect for tomatoes. She sent a heart, not the kind she usually chooses from a sticker pack, but the plain red one that shows up like a period.

Joy asked me, “What do you want to do with the anger that remains?”

“Plant it,” I said, surprising myself. “Use it as mulch. Let it feed different things.”

“Which things?” she asked.

“Boundaries,” I said. “Art. Sleep. Maybe a dog.”

“Get the dog,” she said, and I laughed because the prescription sounded like sane medicine.

I went to a shelter on a whim I pretended was research. A lanky brown mutt with hopeful eyebrows pressed his whole soul against the crate door when he saw me. His name on the card was Captain, which was too much leadership for a creature whose ears flopped like uncertain flags. I knelt. He licked my knuckles with dedication. A volunteer told me his story was ordinary and sad, which is to say, human-adjacent.

“I’ll take him,” I said, and the words left my mouth with a commitment I didn’t need to rehearse. We walked home together, Captain trotting with the relief of a soldier leaving a war he hadn’t signed up for. At the crosswalk, he looked up to check I was still there. I was. I am.

On the first morning, Captain woke me at six by placing his paw gently on my arm like a soft alarm. We walked when the city felt like a promise still being decided. The air held a little bite that made my lungs feel rubbed clean. I thought about the girl who used to check her phone before her feet touched the ground, scanning the day for debt. She is not gone; she just doesn’t run the place anymore.

There were still aftershocks. A cousin sent a long message about how families are complicated and forgiveness is godly and could I please attend Thanksgiving. I said no. Maybe next year. The word maybe felt like a doorway I could close if needed. My father asked if he could bring a casserole to my apartment on a Saturday. I said yes. He arrived with a dish labeled like a science experiment—ingredients, baking time, reheating instructions—as if he was trying to hand me something without strings. We ate on my couch and watched a baseball game on low volume. When he left, he took the dish with him. I stood at the sink and cried for exactly four minutes, a new discipline, then took Captain to the park.

Grace sent me a link to the listing photos—the ones she’d saved before they went dark—to say the buyers had painted the living room a color called “Morning Oat.” “It looks like breath,” she wrote. “They kept the dent in the hallway.”

I looked at the pictures and felt the gentle, necessary ache of a door you closed with love. I wrote to the house again in my head: Be good to them. Let the tomatoes thrive. Creak when it matters. Hold the fights until they’re tired enough to speak truth. Teach their dog where the sunny spots are.

On a Thursday that owned itself, I got home to find an envelope tucked under my door, my name written in a hand I knew. Inside: a copy of the note my mother had written to baby-me, now underlined in two places. On a separate sheet, a new sentence, in her present-tense handwriting that had lost some of its performative loops: I am learning what protection means when you’re no longer a baby. It will take time. I understand there are costs. I am late, but I am here.

I didn’t reply right away. Some messages need to sit on the counter until they reach room temperature. Captain sniffed the paper like he could find the truth with his nose. I put the note in the box under my bed with the other artifacts. Not as a relic for worship, but as a record of weather: this is when the wind changed.

The next week, Joy asked, “What’s the story you’re telling yourself now?”

“That love doesn’t invoice,” I said. “That locks and keys are not metaphors unless you’ve changed them both. That I can be generous and still insist on math. That peace is the sound of my own life at a volume I choose.”

“Good,” she said. “Let’s keep practicing.”

I used to think endings were cliff edges. Turns out, they’re often doors. This one opened onto a hallway with ordinary light, the kind that has to be turned on when the sun goes down, the kind you pay for with a bill that makes sense. I walked down it with the dog, passing frames hung along the wall: a photo of my grandfather smiling with soup in a bowl; a watercolor of tomatoes that looks like a mistake until you stand back; a note that says, simply, porchlight.

There’s a screen between me and the world that no longer smells like a stage. People knock. I look through the peephole. I choose. Sometimes I open the door wide. Sometimes I talk through the lock. Sometimes I don’t answer, and that silence is not a betrayal—it’s a boundary.

They changed the locks. I changed my life. And now when my phone lights up in the morning, it is more likely to be a weather alert or a calendar reminder I set for myself than a demand dressed as a question. I brew tea. I lace my shoes. I feed Captain, who eats with the pure focus of a being who knows how to receive.

When I head out, I turn the key and hear the neat, satisfying snick of a door that doesn’t argue with me. Outside, the city is a symphony of small, sane noises. Inside, my apartment waits without needing me to apologize for leaving or beg to return.

Part 4

In the months that followed, my life learned to count in different units. Not dollars. Not favors. Time, mostly—real time, the kind that isn’t measured by the duration of someone else’s need. Captain learned my routines: the way I wake slowly, the way I hum while making tea, the way I talk to the sink when it clogs like it can hear me bargaining. He’d cock his head, then thump his tail as if to say, I don’t understand your words, but I understand your temperature. You’re safe.

Safe. It’s a small word that used to feel distant, like a light on the shoreline of a lake you swim across every night, never reaching. Now it lived in ordinary places: the hum of my refrigerator, the key on my lanyard, the message from Joy that said simply, No homework this week—notice what doesn’t hurt.

Work settled into a rhythm that didn’t require me to be extraordinary to be enough. Miriam gave feedback like a person who wants you to stay, not like a gatekeeper guarding a prize. I led the project I’d actually wanted, and when my team hit a patch of quicksand, I didn’t offer my body as a bridge. I offered a plan. It worked. We presented to the executives without me translating our worth into self-sacrifice, and still they nodded, still they approved. It felt like discovering gravity again after floating in panic for years.

My grandfather’s health had begun to show its age around the edges—the way he sat down was a little slower, the way he stood up required an extra hand on the armrest—but his mind was a lighthouse. We ate stew once a week through the early cold, then switched to sandwiches as the air warmed and the porch returned to its post. We played a game he invented called “True or Truer,” where he’d offer two statements and I’d pick not which was true, but which allowed for the most honesty.

“True or truer,” he said one Thursday. “You don’t need your mother. Or: You need a mother who behaves like a mother.”

“Truer,” I said. “I need a mother who behaves like a mother.”

“Good,” he said. “Now act like the adult who doesn’t need the first one.”

Sometimes we sat in silence, and it didn’t feel like absence. It felt like respect.

I had decided, as an act of mercy toward my own nervous system, to skip the first Thanksgiving. There was too much choreography, too many possible landmines dressed up as casseroles. But I didn’t want holidays to be a barricade forever. So I started small. A Saturday lunch in a neutral space. The diner with the laminated menu and the pie that revolved like a planet that had finally found a slow and dignified orbit.

My father arrived early, a detail I noted not as proof of love but as proof of effort. He wore the jacket I’d seen in the closet my whole childhood, its elbows shiny with time. He’d brought no speeches, only a new posture: less forward tilt, more square shoulders. I recognized men who are practicing showing up from the way they hold their forks—firmly, as if utensils were a syllabus.

“I told your mother not to come,” he said, not as a decree but as a boundary. “She’s upset. She’s also working at something that looks a lot like humility and not at all like a performance.”

“How can you tell?” I asked.

“She stops when I say stop,” he said. “She apologizes without adding ‘but.’ She doesn’t talk about the locks.”

“Progress,” I said.

“Practice,” he corrected gently. “Progress is what other people notice. Practice is what you do.”

The waitress slid menus under our hands and asked if we wanted coffee. We did. It came in heavy white mugs. We talked about small things that aren’t actually small: the way unions change lives, the way a good bus driver can alter the mood of a route, how early tomatoes should be started in small apartments if you want them to live.

When the bill came, he reached for it. I reached for my wallet, then put it back in my bag. He didn’t make a show of paying. He just paid. On the sidewalk afterward, he tried something new: “Would you like to come by next weekend? I’ll be making chili. Lindsay might bring the kids.”

“Yes,” I said. “Text me the time.” He nodded, accepting that my yes came with the dignity of my schedule.

The “next weekend” plan was his test, but it was mine, too. I wanted something honest and ordinary, the opposite of the spectacle that had defined us. We sat at his table with bowls of chili that tasted like cumin and continuity. Lindsay arrived with the kids, their faces blown open by the kind of sunshine that sees playgrounds in dull light. The littler one climbed into my lap and announced that dinosaurs would be attending the meal in spirit. The older one described his slide-city blueprint like an urban planner with crayons. Lindsay watched them talk with an awkwardness that made me remember how hard learning is. She had a notebook in her bag labeled Budget, and when the kids went to play with measuring cups on the floor like they were toys (they are), she slid the notebook onto the table without commentary. Numbers filled the page in earnest handwriting.

“I’m trying to be boring,” she said, half-smiling. “It’s exhausting.”

“Health is boring,” I said, credit to Joy. “I’m proud of boring.”

“I paid off the shoe store,” she said, so small it might have floated away if not for the weight of her pride.

“Good,” I said. “Next?”

“The emergency card is closed,” she added, and looked at me, waiting for some old script.

I only nodded. “Next?” I said again, and together we listed what no longer owned her. The list dwindled. The children stirred invisible batter in a bowl with a spoon that clinked against wisdom like a bell.

Not everything was tidy. My mother did not attend. She sent pie by my father, and he placed it on the counter like a neutral offering, as if food could be a messenger without a side. There was a note attached, of course. “For your table,” it read, and I appreciated the sentence without letting it borrow trust.

A few days later, she asked to meet. Not to talk, she said in her text. To exchange. The word felt like an attempt at neutrality. We made a plan for a bench in the botanical garden near my apartment, a place where things grow without asking for applause.

She arrived in a coat I remembered from other winters, its belt tied too tight. She sat with a stiffness that made the bench look guilty.

“I brought the baby blanket,” she said, and pulled from her bag a folded square of soft blue that had once smelled like milk. I took it. It felt like a ticket punched in the long hallway of memory. I had brought something too: a photocopy of the ledger from the closing file listing the utilities and mortgage by month, the proof my brain liked to hold even after my heart had agreed to stop counting. I handed it to her. She looked at it the way a person looks at X-rays: blurry to the untrained eye, damning to the trained one.

“I’m not here to relitigate,” I said. “I’m here to return and receive.”

She inhaled slowly. “Return and receive,” she repeated, tasting the verbs. “I am not good at receiving.”

“You stamped your name on the envelopes,” I said. “You were good at collecting.”

She flinched. The truth will do that, but it doesn’t always mean harm. “I thought love meant keeping,” she said. “I thought control was safety. I confused duty with devotion and bills with belonging.” She looked at me in a way that felt like asking permission to continue. “I have started to understand that I can love you without owning you. I am late to this understanding. I do not ask you to be as fast as my regret.”

There are times when you want to be cruel because it would be satisfying, and times when cruelty would only be a way to borrow back the debt you just finished paying. I let the satisfaction pass like a storm cloud. “Thank you,” I said, and meant it. “I can meet you where you are as long as where you are doesn’t trample where I am.”

She nodded like a student copying a formula on the board. “I joined a support group,” she said, and almost smiled. “Everyone is poor and proud. We are trying to learn what money is without shame. Last week they taught us how to read a bill without flinching.”

“That’s advanced,” I said, and we both laughed the smallest, simplest laugh. She reached into her bag again and withdrew a wrapped object, the size of a book.

“I brought one more thing,” she said. “It’s not sentimental. It’s just practical.” Inside the paper was a list titled: Repairs we put off. Under it in block letters: Our responsibility. Next to each item—a roof inspection, the porch rail, the garage door spring—she had written a rough cost and a plan to pay from her income, not mine. There were dates. There were phone numbers. It was a penance of the best kind: not desperate, not public—just competence returning to a body that had outsourced it to me for years.

“It’s a start,” she said.

“It is,” I said. I slid the baby blanket into my bag. I stood. We did not hug. We were not there yet, and that was okay. The garden’s paths curled away from us in invitation. We walked in opposite directions, the way water does when you put your hand in the stream; it goes around you and then toward itself.

Spring arrived sternly, then laughed and softened. Captain and I added new blocks to our morning loop, like a map that kept unfolding, revealing more streets we could choose without needing an excuse. On Fridays, I went to watercolor and painted objects that never paid a bill in their lives: pears, shoes, a chipped mug, a blue door that looked suspiciously like my apartment’s, though I left off the peephole on purpose. I watched colors find each other without me forcing them, and it felt like permission to be wrong and beautiful at the same time.

One evening, Joy asked me to write a list titled “Ways I feel alive that do not require rescuing anyone.” It startled me that I filled the page: running by the lake when the wind is disrespectful; cooking in silence; learning the chords to the one song my grandfather hums; buying a plant and not apologizing to its future; deleting a message without fear the world will end; standing on my porchlight-named savings and feeling it hold.

I bought tomato starts for my own small balcony, even though the sun there is bossy in the morning and stingy by afternoon. I texted Harper to ask how their porch was doing. She sent back a photo of two gangly plants reaching like teenagers. “We named them Mortgage and Forgiveness,” she wrote. “We keep forgetting which is which.” I laughed so suddenly I choked on my tea. “Water both,” I typed. “Just in case.”

There was a day, three months to the calendar from the closing, when the light in my apartment fell in a way that made the dust honest, and for once I didn’t rush to wipe it. I just watched it float and thought, This is what undramatic contentment looks like: dust with no emergency attached. I texted my grandfather a picture and said, Proof of life. He replied with the spoon emoji and a heart, our shorthand for dinner and affection.

The call about him came on a Wednesday. A fall, they said. Nothing broken, they said. Just caution, they said, like caution is a flavor. I took the bus rather than call a car, as if the slowness could talk the world into steadiness. He was propped up in a bed with too much metal and too many beeps, but his eyes were a clear lake.

“I told the nurse you’d come,” he said, smug with accuracy.

“I always do,” I said, and he patted my hand with the back of his fingers like he was putting a seal on a document.

“I am fine,” he said. “I slipped because I was thinking about chili and not about my feet. A man can be forgiven for that.”

“I forgive you,” I said, and he grinned.

He made me promise to take his house key on my ring “just in case,” and the weight of it beside my own key felt like an honor, not a job. That night, after he was settled and the nurse had recruited him to rate the pudding, I walked out into the hallway and let my body shake a little. Old habits return; that old machine of panic wanted to crank up the emergency. I put my hand on my chest, the way Joy taught me, and counted my breath back down from ten. “You are here,” I told myself. “He is fine. You are not an ambulance. You are a granddaughter.”

On the bus home, I thought about keys. How many I had been given without consent. How many I had returned. How this one I had taken by choice. There is a difference you can feel even in your pocket.

The summer unfurled. It brought with it a heat that made people kind in parks and cruel in traffic. Lindsay’s budget grew less tremulous. She texted me a picture of a zero-balance statement with the caption: Look! And I sent back a row of fireworks. My mother learned the bus routes. She sent me a photo of three tomatoes sitting on her balcony rail like patient hearts.

“Tomatoes are heavy for their size,” she wrote. “I didn’t know that.”

“Everything is,” I wrote back. “But some things taste good when you carry them.”

On a Sunday that could have been any Sunday, we tried our first family gathering since the party that had been an execution disguised as a celebration. Small scale. Picnic tables at a public park. No speeches. No slideshow. No microphone begging to be weaponized. My father brought his chili in a plastic container with the lid secured by a rubber band, a safety net for soup. Lindsay brought the kids and paper airplanes. I brought a watermelon, a knife, a roll of paper towels that I knew would be insufficient. My mother arrived last, carrying a bag of ice and looking like a person trying to be a person and not a role. She set the ice down without commentary. She hugged the kids without staging it for a camera. She asked if she could slice the watermelon. I handed her the knife as if it were a diploma.

We ate. We dripped. We wiped sticky fingers and laughed at the way the juice found its way to elbows. Someone’s dog stole a paper plate and fled like a victorious thief; Captain barked once in solidarity, then lay down in the shade with his mouth open like summer was a joke he appreciated. My mother watched me refill cups and said nothing about how I’d always been such a helper. When a bee investigated the watermelon, she did not blame me for bees. When it was time to clean up, we shared the chore like it was a secret we’d agreed to keep. No one asked for leftovers they hadn’t brought. No one made a list of who owed what later. It was a tiny, ordinary miracle. I did not trust it, not entirely. I enjoyed it anyway.