MIL Called My Twins “FAKE GRANDKIDS” at Their Party—Then My 8yo Exposed Her 40-Year Secret

Part I — Paper Wings

The butterfly garlands still moved like soft, bright breathing across our Dallas backyard. Purple and orange tissue wings swayed above the picnic tables; two chocolate butterflies slumped at odd angles on the cake I hadn’t yet had the heart to cover. It had been Juniper and Magnolia’s eighth birthday—our twin girls’ long-planned butterfly garden party—and it ended with a wineglass shattering against the patio stones and the word defective hurled at me like a plate.

I’m Bethany: part-time florist, full-time mom. My husband, Rod, coaches high school football and has spent eight years deflecting opinions about adoption with the stamina of a man who runs wind sprints in August heat. Our twins are kindness disguised as children. And then there’s Gloria—my mother-in-law—retired bank manager, queen of every room with a clipboard no one else can see.

For years she had cut us with polite edges. “Store-bought again,” she’d trill, tapping my cookies like a judge with a gavel. “When I raised Rod and Donovan, there was always the smell of butter and family in the house.” At holidays she thumbed through photos on her phone like a priest counting beads: “See Theodore’s eyes? Donovan’s eyes. And Charlotte has the Peton nose. There’s nothing like seeing yourself reflected back, is there?” Harold, my father-in-law, would cough into his napkin. Rod would squeeze my fingers under the table hard enough to be a promise and a warning at once.

Then the twins asked for butterflies: milkweed and monarch facts and a release at dusk. Gloria surprised us all. She arrived with gardening gloves and seed packets, voice softening as she knelt between our girls and pressed milkweed into the dirt. “Hosts plants,” she explained, and for the first time since I’d met her, she seemed less like a drill sergeant and more like a woman who once looked up.

The party started like magic. Painted Ladies rose out of their mesh tent like pieces of sunrise; one landed on Juniper’s nose and she didn’t move, not even to laugh. Harold brought handmade butterfly houses he’d built in his garage, the purple one carved with tiny spirals that looked like secret handwriting. Even Gloria read The Very Hungry Caterpillar in character voices that made toddlers squeal. For a moment, I believed.

Then the fork chimed.

She stood, pearls bright, smiling that boardroom smile. “Before we celebrate,” she said, “some honesty.”

I felt Rod’s hand find mine. “Mom,” he said under his breath. “Don’t.”

“Eight years,” she announced, “I’ve held my tongue while my son plays house with children who aren’t his. But I won’t pretend anymore. These are not real grandchildren.” She gestured toward my girls—our girls—who had frozen mid-giggle into something like statues. “Some drug addict gave them up; Bethany trapped my son with adopted babies because she couldn’t give him biological ones. And we all nod like fools while cuckoo birds sit in our nest.”

Harold’s chair clattered backward. “Enough.”

She lifted her chin. “I’m the only one brave enough to say what we’re all thinking. Blood makes family.”

Rod stood. “How dare you—”

“They are not your daughters,” she snapped. “Your wife is defective.”

The word broke something old and also new. Maggie started crying into my neck. Parents looked for exits with the panic of people who realize cake cannot fix this, not ever. The yard turned into a theater where no one knew their lines.

And then Juniper stood on her chair.

My quiet child—whisperer of orders at restaurants, shy hand-raiser, small voice attached to a precise spine—stood in her butterfly dress, lifted her chin, and said, “Grandma? Should I tell everyone your secret? The one you told me never to repeat?”

The wineglass fell. The shatter silenced the lawnmower three houses down. For a second the breeze stopped too, as if the butterflies themselves were holding their breath.

Part II — Rosemary

Gloria’s face emptied of color, the way paper drains after you drop it in bleach. “June Bug,” she tried, voice cracking, “you must be confused.”

“I’m not confused,” Juniper said. “When we planted the milkweed, you cried. You said I reminded you of someone named Rosemary you hurt.”

“Stop,” Gloria said, sharp enough to make toddlers cry again.

Rod moved toward his mother. “What did you tell my daughter?”

Harold had gone still—quiet as a turn that breaks an axle. “Gloria?” he asked softly. “What secret?”

Gloria stumbled backward into a chair. For a moment she looked like a girl, not a woman who had made bankers sign things they didn’t want to sign. “Please,” she whispered. “Not here.”

Juniper climbed down from her chair. Maggie, no longer crying, slipped her hand into her sister’s. Two small sentries flanking a crumbling wall. “Grandma told me about her sister,” Juniper said, voice steady. “Her twin sister who was adopted.”

Harold exhaled like a tire losing air. “You don’t have a sister. You said you were an only child.”

“I erased her,” Gloria said. She looked at the ground; when she lifted her face again, the performance had fallen off. “My parents had me in 1962 and adopted a baby two months later. They raised us as twins. I was blonde; Rosemary had dark hair and green eyes that looked like spring. We wore matching dresses. Everyone called us the Peton twins.”

She swallowed. People stopped pretending to leave and stayed.

“When I was fifteen,” she said, “a boy—Daniel Morrison, quarterback, golden, ridiculous—asked Rosemary to dance. Not me. All night. He told his friends she was beautiful and I was the boring sister.” A laugh escaped her—small, furious at itself. “Rosemary tried to talk to me. I screamed at her. I told her she wasn’t my real sister. I said my parents had rescued trash and that she should be grateful. I told her she was stealing my life and that she would never be real family.”

The sentence landed in the yard like a stone in a birdbath.

“She left,” Gloria said. “Climbed out the window with thirty dollars and a backpack. ‘If I’m not real family, I won’t burden you,’ she wrote. They found her under a bridge in Oklahoma City two weeks later. Brought her home. She didn’t talk to me again for four years. We lived together like ghosts. She ate in her room. She walked to school at dawn to avoid me. Then she turned nineteen and died in a car crash on her way to work at a bookstore. The last real words she heard from me were that she wasn’t family.”

Harold made a sound like something metal giving way. “Forty years,” he said. “You burned the photographs. You said there was a flood.”

“I burned them,” Gloria whispered. “I erased her because I couldn’t bear what I’d done.”

She turned to my daughters. “Every time I looked at you, I saw her. Juniper, your quiet and your courage. Maggie, the way you make art and give it away. I told myself blood was what made a family because if chosen love counts, then I killed someone I loved. So I tried to make it not count. I punished you for my guilt.”

Juniper took her grandmother’s hand. “You told me that butterflies come back to the same garden,” she said softly. “So does family.”

Gloria broke. The neighbors—Mrs. Washburn with her hand to her mouth, Coach Marcus pretending he wasn’t filming, Camille very much filming—stood in the part of the yard where you stand during a storm you cannot stop.

“I’m sorry,” Gloria said to the twins, to me, to Harold, to the air. “I am a hypocrite and a coward. I have been cruel because it’s easier than being destroyed.”

“Mom,” Rod said quietly, “you need therapy. Real therapy.”

Gloria nodded like a confession. “Tell me where to go,” she said. “I’ll go.”

Part III — Cocoons

The party unlaced itself. People left with apologies that weren’t theirs to give. We swept up plates that had been abandoned mid-cake. Harold set Gloria on the couch like someone placing something heavy they’re afraid to drop. She talked until her voice gave out: Rosemary’s glow-in-the-dark constellations on the ceiling; the watercolor butterflies she delivered to pediatric wards; the way she sat with kids who ate alone. Every story made Gloria both smaller and more human, a necessary double shrink.

That night Maggie crawled into our bed and twined herself around my arm like she had as a toddler. “Mama,” she said into the dark, “why did Grandma keep it a secret?”

“Because people think if they bury a mistake, it dies,” I said, smoothing her hair. “It doesn’t. It grows in the dark. It makes everything taste wrong.”

“Like a bad garden,” Juniper said from her bed, voice small but awake. “Butterflies need sun. Secrets need shade.”

“That’s exactly right,” I said. “Today you let the sun in.”

Two months later Gloria found a therapist who told her hard truths and didn’t let her hire them away with charm. She joined a grandparents’ adoption support group and sat in church basements under fluorescent hums, reading aloud from a workbook about grief, guilt, and repair. She stopped comparing our girls to Donovan’s kids mid-sentence and learned to start again. “That’s the old Gloria,” she’d say. “Let me try that in a different shape.”

She took the girls to the botanical garden with a specialist who knew native Texas plants and redid the butterfly beds properly: milkweed and dill and parsley, ironweed and purple coneflower, a stand of Turk’s cap for the hummingbirds who complained about being left out. In the middle she placed a small bench with a bronze plaque that read: For Rosemary, who taught us that love makes a family. And for Juniper and Magnolia, who reminded us.

At dinner she asked questions that weren’t tests. “What did you make in art?” she’d say to Maggie, and when Maggie told her about a collage of newsprint and glue, Gloria asked to see it and meant it. “What did you read?” she’d ask Juniper, and when Juniper said a book about monarchs, Gloria asked what it felt like to hold a butterfly without it flying away.

Harold unlearned, too: the habit of swallowing words because his wife preferred rooms where only one opinion fit. He took the girls to Home Depot and taught them the difference between Phillips and flathead and why you never put your fingers near the drill bit even if you’re sure you can control it. He also taught them how to stop a conversation gently when someone says something unkind you don’t have to let live.

Six months after the party, Gloria brought us a letter. “It arrived yesterday,” she said, hands trembling. The return address was Oklahoma City. The handwriting was careful.

Rosemary talked about you all the time, wrote a woman named Patricia who had been Rosemary’s roommate at the adoption support group. She loved you until her last day. She kept one photo in her wallet—two little girls in butterfly costumes, age ten, grinning like twins. She would want you to know she forgave you. She would want you to forgive yourself.

Gloria’s breath left her like a held note finally allowed to end. “I burned everything,” she said. “She kept one I didn’t know about. She kept me anyway.”

Part IV — Metamorphosis

None of this became tidy. That’s not how change behaves. Old Gloria flared sometimes—at a crumpled napkin, a missed piano practice, a Facebook post with a caption she misread. She would close her eyes, inhale, and try again. “I am learning to be the person Rosemary needed,” she said once, surprising herself with the sentence and me with my willingness to believe it.

She volunteered at that same adoption center where Rosemary had given her last years: validating kids at long tables, telling grandparents their insistence on blood was fear dressed as biology, testifying at a state hearing about preserving adopted children’s rights. Not to perform penance. To make different weather.

On the next birthday, we ordered butterflies again. The girls wore wings crafted from felt and wire, and the release went quiet for a second as fifty small orange clouds lifted above us and then decided, collectively, to land on Gloria’s outstretched arms. She cried in the ridiculous way that makes even teenagers look away politely, and then she laughed, ugly and human and always, always late to her own party.

Juniper leaned into me and watched the monarchs open and close like breathing. “Do you think Grandma is a butterfly now?” she whispered.

“She’s still a caterpillar sometimes,” I said, sweeping hair out of her eyes. “But she is making something. And she is letting us see it happen.”

When I tuck the girls in, I say all the lines mothers say and some we invent. Glow-in-the-dark stars map a ceiling above them like a kept promise. On the dresser is the one photo Gloria did not burn: two ten-year-old girls dressed as butterflies in 1972, faces open, wings crooked. Next to it is a new photo: two eight-year-olds at a picnic table, one standing on her chair, not a wing in sight, just a spine that remembered it had always been there.

Sometimes I go out to the garden at dusk and put my hand on Rosemary’s bench. I don’t talk to her. She is not a saint; she is a girl who should have been allowed to grow up. But I thank her anyway, because it’s possible to be grateful to a person for surviving you long enough to teach you how to love someone else better.

Family secrets don’t disappear in dark closets. They molt. They change shape until they are too big to ignore. Our secret burst out of a woman who had spent forty years insisting blood is the only map that matters and landed in the mouth of a small girl who had just been told she didn’t belong.

Juniper asked a question. It became a key. It opened a door Gloria had nailed shut so long ago she’d forgotten where the hinge was.

At the end of the party that started everything, when the trash bags were full and the cake was drying in cold, hard rosettes, Juniper slid her hand into her grandmother’s. “You can tell us about Rosemary whenever you want,” she said. “We can be your garden.”

Gloria nodded like a vow. “And I will plant every day,” she answered, “until the butterflies come home.”

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. Navy SEAL Asked Her Rank As A Joke — Then Captain Made The Entire Base Go Silent

Navy SEAL Asked Her Rank As A Joke — Then Captain Made The Entire Base Go Silent Part I…

CH2. My Sister Slapped Me At Family Dinner And Mom And Dad Clapped Behind—So I Gave Her Five Minutes To…

My Sister Slapped Me At Family Dinner And Mom And Dad Clapped Behind—So I Gave Her Five Minutes To… …

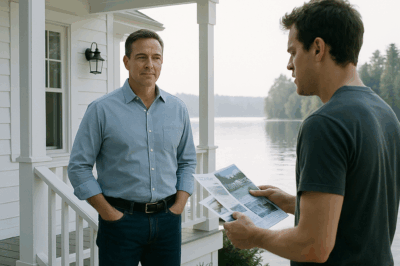

CH2. My Nephew Wanted To Turn My Lakefront Cottage Into His Airbnb, So I Prepared A “Surprise.”

My Nephew Wanted To Turn My Lakefront Cottage Into His Airbnb, So I Prepared A “Surprise.” Part I —…

CH2. My Brother Laughed at My Father’s Funeral—Then a Nurse Handed Me an Envelope That Changed Everything

My Brother Laughed at My Father’s Funeral—Then a Nurse Handed Me an Envelope That Changed Everything Part I At…

CH2. HOA Karen Calls 911 After Her “Master Key” Can’t Open My Lake Cabin — Unaware My Son Is The Sheriff!

HOA Karen Calls 911 After Her “Master Key” Can’t Open My Lake Cabin — Unaware My Son Is The Sheriff!…

CH2. You Earn $3K, Why Is Your Child Hungry? DAD Asked “My Husband Proudly Said, I gave Her Salary To..

When Dad came to take my son for the weekend, he opened the fridge — it was completely empty. Shocked,…

End of content

No more pages to load