Japanese Couldn’t Believe One P-61 Was Hunting Them — Until 4 Bombers Disappeared in 80 Minutes

Why Major Carroll Smith used radar to hunt Japanese bombers in total darkness during WW2 — and destroyed 4 aircraft in 80 minutes. This World War 2 story reveals how the P-61 Black Widow’s secret radar made night invisible.

Major Carol C. Smith knew the sound of fear disguised as routine.

It was in the way the generators thumped a little too loud in the humid Philippine night, in the way the ground crew shouted over them with forced jokes, in the way every glance slid once, just once, toward the north where the black sky swallowed everything.

On the perimeter of Meuire Field on Mindoro, the jungle was a dark wall, broken only by the occasional wink of a cigarette where a sentry stood watch. Beyond that—the sea, then the empty black vault of the sky, and beyond even that, somewhere out there, twelve Japanese bombers flying on a course they had flown every night for two weeks.

The Americans had given the numbers a kind of bitter rhythm. Three hundred and thirty-four air raid alerts in fourteen days. Twelve bombers each time, sometimes more, sometimes less. Engineers joked that they could mark time by the shriek of distant anti-aircraft guns.

No one laughed too hard.

Near the center of the field, lit by hooded lamps throwing pools of yellow on the coral runway, the P-61 Black Widow crouched like something alive. It was a big, sinister shape: twin booms, broad wings, a fat fuselage with a glassed-in nose. Painted deep black, it seemed to drink in the light rather than reflect it, a shadow pretending to be metal.

The ground crew had already pulled the wheel chocks away. The props of the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines were still. For the moment, the Black Widow was silent.

Major Smith stood by the left main wheel, helmet under his arm, looking up at the aircraft that had become both his weapon and his refuge. Twenty-six years old, he’d flown fighters for years and combat for months, but there was still a part of him that couldn’t quite believe he was about to go hunting in the dark based on nothing more than the ghostly green glow of a radar scope.

Porter was already climbing the ladder into the radar compartment, a bundle of cables and dark flight gear silhouetted against the fuselage. Lieutenant Philip Porter was slim, sharp-featured, with the permanently squinting eyes of someone who had spent too much of his life in dim rooms staring at glowing lenses. Six months of tracking targets on scopes from New Guinea to Morotai had given him the kind of calm you didn’t learn in peacetime.

“You look like hell, Phil,” Smith said up to him, a half-smile pulling at one corner of his mouth.

“Feel like it too, Major,” Porter replied. “But these boys out there in tents have it worse.”

Smith glanced past the P-61. All around the field, beyond the hard-packed coral and pierced steel planking, there were tents—rows and rows of them. Engineers, aviation mechanics, truck drivers, infantrymen waiting for their next assignment. Twenty thousand men sleeping restlessly under tarps and canvas, trusting a handful of aircraft and some searchlights to keep the night from killing them.

Beyond the tents, as far as anyone cared to walk, men were working even now by lamplight and truck headlamps: filling in coral, grading dirt, hammering down more planking. The airfields they were building would let fighters fly cover over the Lingayen Gulf landings. Without them, the invasion timetable stretched into a nightmare of unopposed Japanese air attacks.

“If they get through again tonight,” Smith said, voice low, “we’re gonna be picking up a lot more than shovels out there tomorrow.”

Porter didn’t answer. He didn’t have to. They both knew what was at stake.

Three days earlier, on December 26th, the 418th Night Fighter Squadron had arrived at Meuire Field. They’d come in on skeletal runways, dodging debris and equipment, hardly believing this rough strip was where they were supposed to operate from. But the engineers were geniuses of speed and desperation. Every day another few hundred feet of runway became usable. Every night the Japanese tried to take it all away with high explosive.

The day the 418th arrived, the Japanese had hit the field twice.

Meuire Field and the sister strip under construction beside it were the only lifeline for the invasion planners. From here, in a matter of days, P-51 Mustangs and P-47 Thunderbolts would fan out to cover the next major move in MacArthur’s great return to the Philippines. The Japanese understood that as clearly as the Americans. That was why bomber crews were climbing into their own planes somewhere north even now, believing the darkness made them safe.

Smith tightened the chin strap of his helmet by reflex and glanced at his wristwatch.

Eleven thirty-nine.

He felt, rather than heard, the base’s nervousness. The way the chatter in the ops shack had dropped in volume when someone announced twelve bogeys on the way. The way the anti-aircraft crews were already at their guns, faces painted in smears of lampblack, scanning a sky that didn’t yet show anything at all.

A truck rolled past, flatbed piled with ammo crates. A private on the back crossed himself quickly and glanced away when he realized someone had seen him.

“Major.”

Smith turned. The squadron’s operations officer, Captain Hayes, walked up in a hurry, ducking instinctively as he passed under the Black Widow’s massive wing.

“Radar picked up something?” Smith asked.

Hayes thrust a thumb back toward the crude operations hut, where a generator hummed and threw out ozone and hot oil smell.

“SCR-270 station up the coast just passed word,” Hayes said. “Big group at about twenty thousand, and a second cluster lower, all coming from the north. Our GCI boys think it’s twelve, maybe more.”

“Same pattern,” Smith said.

“Same pattern,” Hayes agreed. “They’ve hit us every night, but this is the first night you and Porter are ready with the Widow.”

He tried to sound optimistic. It came out tight.

Smith looked back up at his aircraft—at the bulbous nose housing the SCR-720 radar antenna, at the cannon ports under the belly, at the sleepy, predatory lines of the twin booms.

“This thing works like they say it does,” he said, “tonight’ll be the last time they come in here like they own the dark.”

Hayes managed a crooked grin.

“You bring down even two of those bastards, it’ll be worth it,” he said. “Good hunting, Major.”

Smith nodded once. No dramatics, no big speech. He turned and climbed the ladder into the cockpit.

The Black Widow’s cockpit was not made for comfort. The pilot sat high in front, surrounded by framework and glass and metal and instruments. Behind him, separated by a short tunnel, sat the radar operator in his own little cocoon of dials and scopes.

As soon as Smith settled into his seat, his world narrowed. The night outside became just a dark halo beyond the green glow of the instrument panel.

He went through the motions his hands knew better than his conscious mind. Battery on. Magnetos. Mixture rich. Fuel selectors checked. The smell of aviation fuel and burnt oil seeped in around the canopy frame, familiar and grounding.

In the rear compartment, Porter buckled himself in, headset on, flipping switches of his own. The radar set hummed to life, vacuum tubes warming, the dish in the nose beginning to sweep its invisible beam across the sky.

Smith keyed the interphone.

“You back there, Phil?”

“I’m here, Major,” Porter’s voice crackled in his ears. The intercom flattened all emotion into the same metallic tone, but Smith had flown with Porter long enough to hear the subtle difference when the man was thinking fast. “Scope’s up. GCI station is passing us the first vectors as soon as you’re airborne.”

Smith signaled the ground crew with a raised hand and two fingers twirled in the air. The crew chief gave him a thumbs up and stepped clear.

“Meuire Tower, Night Fighter Eight-Two is ready for takeoff,” Smith said on the radio.

There was a hiss of static, then the controller’s voice.

“Night Fighter Eight-Two, cleared for immediate takeoff. Good hunting.”

Smith eased the throttles forward. The twin R-2800s coughed once, then caught and roared, propeller discs becoming silver blurs in the night. The aircraft shuddered as it rolled, heavy on the rough coral.

For a moment, the runway lights—twelve kerosene pots in a line—were all he could see ahead. Then the nose lifted, the rumble of the wheels on the crushed coral vanished, and the P-61 was in its element.

The ground fell away into darkness. The Black Widow climbed into a sky that looked no different from the ocean below.

“Gear up,” he said aloud, mostly for his own rhythm, even though his hand was already on the lever.

Behind him, Porter’s hands moved over knobs and switches, tuning gain, adjusting sweep, making the invisible visible.

The Black Widow’s cockpit instruments glowed faint, ghostly white and green: airspeed, altitude, artificial horizon, fuel gauge—all obedient little circles and needles, telling him he was climbing through five thousand feet, then six, then eight.

Outside, Smith could see nothing. No stars—cloud deck above. No horizon—just black. The only proof that the sky existed at all was the faint tremor of the airframe and the way the engines’ noise changed with altitude.

“Night Fighter Eight-Two, GCI,” a calm voice came into his headphones. “We have multiple bogeys north of you, bearing zero-two-zero, angels eight to twenty, speed one-eight-zero knots. Vectoring you to intercept lower group.”

“Roger, GCI,” Smith replied. “Heading zero-two-zero, angels eight.”

He turned the P-61, trusting the compass and the glowing gyro.

In the back, Porter frowned at his scope as the sweeping line painted and repainted the sky. The main scope showed azimuth, the left-right bearing of returns. The elevation scope showed whether they were above or below.

He’d trained for this in Orlando, Florida, but Florida had been a place of warm nights and practice blips, of instructors leaning over his shoulder and correcting his vector calls. New Guinea and Morotai had been harder—mountains, storms, Japanese raiders that sometimes showed up and sometimes didn’t.

Tonight, the air over Mindoro was thick with possibility.

“I’ve got something,” Porter said quietly. “Bearing zero-three-five, range five miles, angel eight, speed one-eight-zero. Looks steady.”

Smith’s heartbeat kicked once against his ribs.

“That’ll be one of them,” he said. “Take us in.”

“Come right ten degrees,” Porter said. “Level at eight thousand. Range closing—four miles… three point five…”

In the rear compartment, his world had shrunk to the green-lit circle of his scope. Little blips, phosphor marks, brightening and fading. The skill was in knowing which was which—ground clutter, friendly aircraft, weather, or the enemy.

It was like listening for a specific voice in a crowded bar.

“Range three miles,” he said. “He’s bearing zero-three-five, slightly right. Little below us now. Speed holding one-eight-zero. Looks like a Betty.”

Smith’s left hand rested on the throttles, right hand light on the control yoke. He couldn’t see the other aircraft yet. There was nothing out there but black.

But on his panel, a smaller radar repeater—slaved to Porter’s set—flickered on. A single dot glowed at the edge of the range ring, creeping inward.

His mouth was dry. He swallowed and forced himself to breathe steadily.

“Range two miles,” Porter said. “Come left five degrees… that’s good. Drop fifty feet. He’s dead ahead now, Major. Straight and level. No jinking. No altitude change.”

Smith could almost see them in his mind: seven men in a Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber, instruments lit dim green, the glow of a cigarette hidden under a navigation table, the faint murmur of engines. Maybe someone was thinking of home, of a wife or a child, of the promise that flying night missions over the ocean was safer than the brutal daylight brawls over Leyte.

They believed the dark hid them.

Smith nudged the nose down and let the P-61 settle, slipping into the bomber’s blind spot—below and behind.

The blip on his radar repeater crept inward. Twelve thousand feet of air existed between him and the ocean. At this altitude, there was no visual reference, nothing to tell you if you were three hundred yards from another aircraft or three miles—unless you had radar.

“Range one mile,” Porter said. “He’s still straight. Still blind. You should pick him up visually shortly—look just above your nose, maybe a hair to the right.”

Smith squinted into the black ahead. At first, he saw nothing at all.

Then, as his eyes adjusted, he caught it—a faint, fuzzy smudge against a slightly lighter patch of cloud. Two pinpricks of orange, the exhaust flames from the Betty’s engines, muffled and subdued by night-flying baffles but still there for eyes that knew how to look.

“There you are,” he murmured.

He eased the Black Widow closer. The heavy fighter responded like a big cat, slow and deliberate, not the skittish twitchiness of a single-engine day fighter. The engines purred, power steady.

“Range eight hundred yards,” Porter said. “You’re closing nicely.”

Smith’s right thumb flicked the arming switches for the four 20mm cannons mounted in the belly. A small red light winked on.

He brought the glowing ring of the N-6 gunsight to bear, ghostly lines hovering against the darkness. The silhouette of the bomber settled into the circle. He adjusted his aim, a little low, a little behind—just like they’d taught him.

This is what those eighteen months of training had been for. Night navigation. Night gunnery. Mock interceptions. Blind approaches.

“Range six hundred… five hundred…” Porter’s voice was steady. It made it easier for Smith to keep breathing.

At four hundred yards, he stopped listening and started feeling.

His world shrank to the reticle, the faint outline of wings, the glow of exhaust.

He squeezed the trigger.

The Black Widow shuddered as the cannons spat fire. The noise was a sharp, chest-thumping roar even over the engines, a rapid hammering that seemed to vibrate his teeth. Brilliant red tracer streaks reached out, vanishing into the dark, then erupting against metal.

He held the trigger for two seconds. He could almost count it out: one Mississippi, two—

He released.

In those two seconds, forty-eight rounds of high-explosive 20mm shells had left the gun barrels at over 2,800 feet per second.

Half of them tore into the Betty’s right wing.

The effect was immediate and horrifyingly beautiful. A flash blossomed where the fuel tank was, orange-white and sudden, ballooning out into a flower of fire. The right wing shattered, fabric and aluminum and fuel vapor turning into a brief, violent sun against the night.

The bomber rolled abruptly, a lurching, involuntary motion, as if a giant hand had slapped its side. Its nose dropped. It fell into a steep, flaming dive.

For an instant, the fires from the wreck lit the cloud base below—a ghostly, flickering reflection. Then the burning aircraft plunged into that haze and vanished.

Seconds later, a dull, distant orange flash erupted far below as the Betty met the sea.

“Splash one,” Porter said softly.

Smith exhaled slowly, as if he’d been holding his breath the whole time.

“Time?” he asked.

“Twenty-three fifty-seven,” Porter said. “Three minutes before midnight.”

Smith glanced down at his fuel gauge. The needle had barely moved, but he knew the numbers. Fifteen percent of their fuel burned already. One bomber down. Eleven more out there.

He felt a flicker of something that wasn’t quite victory.

It was mathematics.

One aircraft, twelve bombers, three hours of fuel. If he spent ten minutes on each, he could maybe intercept three or four. The rest would slip past, dropping bombs onto the crawling construction sites where Americans sweated under hard hats by day and tried to sleep by night.

Pressure sat on his shoulders like an extra layer of gear. Every choice, every vector, every minute used on one target was a minute lost for another.

“GCI, Night Fighter Eight-Two,” he said into the radio. “We have one Betty destroyed, approximate splash eight miles north of Meuire. Request vectors to next nearest target.”

Static crackled, then the ground controller’s voice came through, more excited than before, but trying to maintain its professional calm.

“Eight-Two, GCI. Good work. Multiple bogeys still inbound. Stand by for vectors from your onboard radar. Our scope is cluttered as hell.”

Porter’s hands were already moving. The Betty’s blip had winked out. Others remained. He turned the gain up slightly, filtering out ground returns, isolating the moving specks.

“I’ve got at least three more contacts,” he said, frowning. “They’re spread out—different altitudes, different distances. These guys aren’t flying in tight formation. Smart.”

“They’re learning,” Smith said. “Call me the closest one.”

Porter checked ranges, bearings, altitudes. He worked fast, his brain running through geometry without consciously thinking in those terms.

“Second bandit, bearing one-eight-zero, angels six, range six miles and closing,” he said. “He’s south of our last intercept point—heading straight for the airfield.”

“Then so are we,” Smith replied.

He pushed the throttles forward. The R-2800s responded with a deeper bellow, the aircraft’s nose tilting down as it accelerated.

The Black Widow ate distance quickly, but time ate fuel quicker.

“Range five miles,” Porter said. “Speed on target looks like about one-nine-zero knots. Another Betty, I’d bet my mom on it.”

“Let’s save the bets for after the war,” Smith replied. “Talk me in.”

Behind him, Porter gave calm corrections, adjusting their approach by a few degrees at a time. Left five. Down two. Right three. As they closed, Smith’s own radar repeater again picked up the blip, giving him a personal fix.

Out over the black Pacific, the second Japanese bomber droned along, steady as a train on tracks. The crew might have been alert, or they might have sunk into the strange, exhausted stupor that long flights over featureless sea induced. The dial of the clock on their panel ticked toward minutes that would never mean much to anyone but them.

When Smith finally saw them, they were lower than the first Betty—six thousand feet—and closer to the unbroken curtains of cloud.

He eased the P-61 into position, below and behind, the same attack pattern. It was temptation itself to get creative, to try something “better.” Training told him: repeat what works. The more variables you add, the more ways things can go wrong in the dark.

At five hundred yards, he could see the shape of the fuselage, the twin engines. No searchlights, no flares. No hint, yet, that they knew a killer was pacing them in the dark.

He squeezed the trigger at 350 yards.

Again, the Black Widow’s cannons roared. Again, red streaks tore through the night.

The shells walked across the Betty’s right engine. Fire blossomed there first, then crawled along the wing to the center section, licking at the fuselage. The bomber began to sag, nose dipping, then rolled, both wings now burning, turning it into a crucifix of flame.

Smith broke left and pulled up to avoid flying through the debris. Through his canopy he saw the bomber tumble, a spinning wheel of fire that fell until the night swallowed it.

It hit the water at nineteen minutes past midnight.

“Two,” Porter said flatly. “Two Bettys down. Radar shows their tracks terminating.”

Smith checked his fuel again.

Forty-two percent gone. Their internal tanks, full of 646 gallons when they’d taken off, were now nearly half-empty.

He had intercepted two bombers in less than thirty minutes. That was the good news.

Ten more were still out there. That was the reality.

On the ground at Meuire Field, the air raid sirens had gone from distant background to brain-piercing reality. Engineers tumbled out of their tents and dived for slit trenches, cursing and clutching helmets. Anti-aircraft crews earnestly scanned the sky, hearing the distant drone of engines but seeing nothing.

In the temporary operations shack, maps and cigarette smoke battled for dominance. Officers bent over the radar repeater from the GCI site, watching green smears move and vanish, correlating them with radio reports from Smith and from coast watchers along the shore.

“All right, this one’s gone,” someone muttered as a track terminated eight miles north of the field. “That’s two. Where the hell are the rest?”

Outside, someone pointed randomly at the sky.

“There! I see one! No, wait… that’s just a cloud.”

After two weeks of nightly raids, the nerves of Meuire’s garrison were a frayed rope. They were bitterly aware of the vulnerability of men, fuel, and equipment sprawled under thin canvas and hastily bulldozed berms.

Two bombers down meant a third less destruction, a third fewer bombs. But if even one got through, it would still mean death, maybe to people whose names Smith would never know but would carry on his conscience anyway.

Up in the P-61, the cockpit smelled of cordite now, a harsh tang layered over the oily sweetness of fuel and hot metal. Empty shell casings rattled faintly in their chutes.

Porter didn’t give him time to dwell.

“Third contact at angels nine,” he said. “Bearing one-six-zero, range seven miles. This one’s jigging around, though. Not flying straight like the others.”

“Somebody up there has their finger on their neck,” Smith said. “Could be someone finally put two and two together and realized their friends are not returning.”

He pulled the aircraft into a climb. The engines roared, the Black Widow’s nose pointing at nothing, and the altimeter unwound numbers.

As they climbed, Porter studied the jittery motion of the blip.

“This one’s not a Betty,” he said. “Speed is closer to two hundred. See that? He keeps changing altitude by two or three hundred feet at a time. Small turns. Pilot’s no dummy.”

Smith’s lips pressed into a thin line.

“Helen?” he asked.

“Could be,” Porter said. “Nakajima Ki-49. Faster. Better defended. They’ve got a tail gunner who can throw lead straight back at us.”

“Fun,” Smith said dryly. “All right. Let’s see how smart he really is.”

He remembered lectures back in training, grainy silhouettes on classroom walls. The Ki-49 “Helen” with its gun blisters and armored nose. Its specs weren’t so different from the Betty in terms of speed, but it had that crucial difference—a better field of fire to the rear.

Flying straight up behind it would be like sticking your head in a beehive.

They reached nine thousand feet just before twenty-three minutes past midnight. The blip on the scope danced, still jinking.

Porter murmured corrections, predicting its movements as much as reacting. The Helen’s pilot seemed to be following some instinctive pattern: gentle turn right, small climb, gentle turn left, small descent. Not enough to throw a determined pursuer off, but enough to complicate radar tracking.

It was a little dance of fear and professionalism.

Smith eased the Black Widow in, this time offset to the left and a bit lower. The bomber’s belly was poorly defended, like most Japanese designs. They’d prioritized offensive capabilities and range over armor and coverage for the underside. In the bright days over China and New Guinea, that had been enough. At night, with a silent hunter tracking them by radar, it was a glaring weakness.

“Range one mile,” Porter said. “He’s still turning. He’ll break right again in three… two… now.”

On the scope, the little comet tail of the blip curved. Porter had read the pilot’s pattern.

“Come right with him, Major,” he said. “Keep it smooth. Range eight hundred yards. You should see him now—slightly above your nose, low cloud background.”

Smith peered ahead. For a brief moment he saw nothing. Then a shape slid out of the black—a darker wedge against dark, ghostly. No bright exhaust this time; the Helen’s engines were tuned, baffled, running lean.

Only the faint glimmer of reflected light from some panel angle betrayed it.

He slipped under and left, keeping clear of the direct line behind the tail. At best, the tail gunner would have to shoot down at an awkward angle. At worst, he wouldn’t see the P-61 at all until too late.

The gap closed.

At five hundred yards, the Helen’s crew finally realized something was behind them.

A tongue of red tracer spat from the rear cockpit, wild at first, then narrowing as the gunner walked his fire across the sky.

“Taking fire,” Porter said evenly.

Tracer streaks zipped past Smith’s canopy, close enough that he could see their tiny glowing cores, hear one or two crack against the fuselage. A small spiderweb of cracks appeared low in his windscreen where a stray round had glanced off.

He felt, not for the first time, the cold realization that there was nothing but metal and a couple of inches of glass between him and emptiness at 9,000 feet.

He forced himself not to flinch. Flinching meant jerking. Jerking meant missing. Missing meant giving the bomber time to turn, to dive, to make this encounter a drawn-out slugging match.

He steadied the gunsight, letting the Helen’s bulk settle into the ring.

He squeezed the trigger and held it for three full seconds.

Seventy-two rounds poured out, a pig-iron waterfall of high explosive.

The first shells struck the plane’s belly, knocking chunks of metal away. Then they climbed along the fuselage, punching ragged holes. One burst tore into the right engine. Another raked across the base of the tail. An instant later, the entire right side of the bomber lit up, the engine erupting in a cloud of flaming debris.

The Helen rolled abruptly, right wing dropping. For a second, it hung almost upside down, then tipped fully over into an inverted spiral.

“Pull off, Major!” Porter shouted.

Smith was already banking hard left, pulling up, feeling the G’s squeeze blood out of his head. His vision narrowed at the edges, a gray curtain threatening. He grunted, tightened his stomach muscles, kept his breathing steady.

The burning bomber spun below him, a ragged pinwheel of fire. Any shapes inside it were lost in the glare. At seven thousand feet the wing separated. At six thousand the fuselage broke. At five thousand there was nothing left but flaming fragments.

Another dirty orange flash marked where the pieces met the ocean.

“Third one’s gone,” Porter said softly. “Time zero-zero twenty-nine.”

Smith let out a breath that felt like it had been trapped since takeoff.

“How’s our gas?” he asked.

There was a moment of silence, as if Porter was reluctant to confirm what they both knew.

“Twenty-eight percent,” he said. “Major… that’s below the normal minimum to start home. If we were being timid, we’d already be pointing our nose south.”

Smith eyed the fuel gauge. The needle looked like it was in the bottom half of the dial, exactly where he expected—but somehow more ominous now that the numbers were spoken aloud.

He thought about the field—little lines of lights, men huddled in trenches, engineers lying awake listening for bombs that might never come.

“What about the others?” he asked.

Porter didn’t argue. He turned back to his scope.

“There’s one more contact in our immediate area,” he said. “Angels four, bearing one-seven-zero, range nine miles. That’s the one we passed up earlier, the low guy. He’s now about twelve miles north of Meuire, heading straight south.”

Smith pictured a bomber flying at four thousand feet, closer to the ground, almost in reach of the AA guns that ringed the field. Closer also to the searchlight cones that were starting to probe the sky near the airstrip.

“He’s almost to the dance,” Porter added. “If we don’t get him, someone on the ground will have to try while he’s dropping bombs on their heads.”

Smith didn’t need the moral arithmetic spelled out. He was already turning the Black Widow’s nose toward the south, descending.

“Let’s go get number four,” he said.

Out over the ocean at four thousand feet, another Betty droned steadily toward Mindoro. Its pilot had flown this route for nearly two weeks. He knew the timing of the air raid sirens on the island, the approximate positions of searchlights, the bursts of flak he’d started to see reach a little higher each night.

He did not know that three of his comrades were already burning oil slicks on the surface of the sea behind him.

He did not know that an enemy fighter was silently sliding into position behind him, guided by radio waves bouncing off his own aluminum skin.

He had his own worries—engine temperatures, fuel, whether the heavens would be generous and guide his bombs onto the American construction site. Maybe he thought, briefly, of his wife. Maybe of his father’s stern approval when he’d enlisted. Maybe of death as an abstraction rather than a near certainty.

In the Black Widow, Smith descended through five thousand feet, then four, leveling off slightly above the bomber’s altitude.

“Range four miles,” Porter said. “Three. Two. He’s not jinking. This one thinks it’s just another routine run, Major.”

Smith could see the searchlights from Meuire now—their beams thin and pale from this distance, sweeping, crossing, probing. Occasionally they flared on some cloud, casting eerie, moving pools of brightness that made the sky seem alive.

The Japanese bomber was flying straight toward those beams.

“Visual at one mile,” Smith murmured. “Got him.”

The Betty was a darker smudge against the faint reflection of the searchlights on the clouds below. For a second, Smith thought he saw something flash in one of its dorsal blisters—maybe a crewman stretching, maybe just sunlight that didn’t exist.

He slipped down and in, behind and below, the attack pattern so familiar now he could almost do it in his sleep. The Black Widow’s engines were throttled back, exhausts masked as much as possible. At night, you wanted to be a ghost.

At three hundred and fifty yards, with the bomber framed perfectly, he checked his ammo gauge. Five hundred and twelve rounds remaining. Enough for perhaps three good bursts.

“Fuel?” he asked.

“Twenty-three percent,” Porter replied.

One more intercept meant dipping below every safety margin they’d ever talked about back in training. There would be no missed shots. No long chases. One pass, one burst, then a straight line home.

He didn’t hesitate.

He squeezed the trigger.

The cannons barked again in a two-second burst. Forty-eight rounds, same as the first and second kills.

This time the shells tore into the center of the Betty’s fuselage and along its port wing. The left wing’s fuel tanks ruptured, streaming vapor that caught fire an instant later. The wing tore free, ripping itself from the bomber’s body in a scream of metal, spinning off into the dark like some flaming, broken branch.

The Betty rolled violently into the gap, then pitched nose-down. Fire consumed the remaining wing as the aircraft fell, a long, twisting comet of flame and aluminum.

It impacted the sea a minute later in a blossom of spray and smoke.

“Four,” Porter said. “Four bombers down. Time zero-zero thirty-five.”

Smith broke off, letting the wreck fall behind him. The searchlights from Meuire now were brighter, fanning across the northern approaches. The base was fully awake.

He turned the P-61 toward home.

“How many contacts left out there?” he asked.

Porter scanned the scope. The blips that had been steadily crawling southward were now doing something else—some turning, some fading.

“Most of them are breaking off,” he said. “Eight, maybe nine aircraft turning away, heading back north or northwest. Whatever they saw or heard—maybe the explosions, maybe some warning from their coastal radars—that was enough. They’re bugging out.”

“So they finally realized the dark isn’t theirs anymore,” Smith said.

He felt a grim satisfaction. Four bombers destroyed, the rest driven back. No bombs falling on the airfields. No engineers killed in their sleep.

He checked the fuel gauge again.

Twenty-one percent.

He did the math in his head. Meuire Field lay about eighteen miles to the south. At cruise, the Black Widow drank about 100 gallons an hour. Twenty-one percent meant around 136 gallons left. At 280 miles per hour, that was enough for roughly forty minutes of flight in perfect circumstances.

But circumstances in war were never perfect.

“Let’s get home,” he said. “I’d like to land while there’s still gas for a go-around if I bounce it.”

“Agreed,” Porter said.

Smith trimmed the aircraft for cruise, throttling back, letting the speed settle. For the first time in an hour, he loosened his grip on the yoke, rolling his shoulders to relieve cramped muscles.

Porter kept one eye on the scope as the coastline of Mindoro slowly grew thicker, a smudge of land where there had been only black before.

“Contact,” he said suddenly.

Smith’s head snapped around instinctively, even though there was nothing to see.

“Where?”

“Dead ahead of us, about four miles, angels seven, heading north,” Porter said. “It’s between us and home.”

“Another bomber?” Smith asked.

“Speed’s higher,” Porter replied. “That’s doing about three hundred ninety. That’s no Betty.”

Smith’s mind pulled up silhouettes again. He didn’t need to be told.

“Frank,” he said. “Ki-84. One of their hot rods.”

The Japanese Hayate “Frank” was one of the best fighters the enemy had produced—fast, agile, well-armed. In daylight, in a turning fight, it could dance around a heavier aircraft like the P-61, ripping it apart with cannon fire if the pilot was any good at all.

But this wasn’t daylight.

“Major,” Porter said carefully, “we are at nineteen percent fuel. That’s about twenty-five minutes, maybe less if we push it. If we engage this guy and we have to chase him, we could wind up swimming.”

“Where’s he headed?” Smith asked.

“North,” Porter said. “Away from the field. But we don’t know if he’ll turn back in the next ten minutes. He could be a recon job. He could be setting up for a later run.”

Smith stared at the faint, glowing blip on his own repeater. It was moving toward them, their closing speed bringing them together in the dark.

He thought about the engineers on the field he’d just protected. Thought about them stretching as dawn came, getting back to work, trusting that their own air force controlled the sky. Thought about what one determined fighter could do strafing an airfield full of aircraft and fuel.

If he let this one go and it came back, and men died because he’d chosen his own fuel over their lives, he wasn’t sure he could live with that.

He nodded once, alone in his cockpit.

“All right,” he said quietly. “We’re already borrowing tomorrow’s luck. Let’s go all the way. Vector me.”

Porter’s sigh was almost inaudible over the intercom.

“Coming left ten degrees,” he said. “Climb to seven thousand. He doesn’t know we’re here. Yet.”

The P-61 banked again, engines spooling up. Smith watched the Frank’s blip slide across his range ring, moving from ahead to slightly right, the distance shrinking.

He kept his eyes outside, even though there was nothing but black. It felt wrong not to look.

At eight hundred yards, he finally saw a shadow—a speck against the sky, slightly lighter where the clouds reflected faint starlight above. No exhaust glows this time; the Japanese pilot ran dark.

Smith crept up from below and behind. The fighter was small, sleek, a knife compared to his sledgehammer. Pilots in the mess tent liked to argue about which airplanes were the prettiest or the deadliest, trading posters, trading silhouettes. Looking at the Frank, he had to acknowledge its lethal grace.

“Range five hundred,” Porter said. “He’s straight and level. Probably hasn’t seen us.”

Smith eased closer.

Four hundred yards. Three hundred and fifty.

He could smell his own sweat now, under the oil and cordite. His suit was damp in the small of his back. His throat felt thick, dry.

His fuel gauge had ticked down again—seventeen percent. There would be no second pass.

He set the gunsight ring on the fighter’s tail, slightly offset to account for closing speed. The crosshairs hovered over where the pilot sat, hidden behind armor and metal.

“Three hundred,” Porter said. “He’s still blind. Take your shot whenever you’re ready, Major. This is the one that counts.”

Smith’s finger curled on the trigger.

He thought, very briefly, about the man in that cockpit ahead—a Japanese pilot, maybe twenty-two, maybe thirty, who had done his own share of training and worrying and joking around mess tables. A man who had climbed into his aircraft tonight just as Smith had climbed into his, believing in his own mission.

War didn’t care about the symmetry.

He squeezed the trigger and held it.

The cannons bellowed, louder than they had all night. Seventy-two shells flew out in three seconds, an extended burst that drew red lines across the darkness. Half of them struck the Frank.

The tail section disintegrated in a shower of fragments. Shells walked up the fuselage into the engine cowling. The engine erupted, flames bursting from the seams. Black smoke streamed back, a dark smear even against the black sky.

The Frank rolled right, nose dropping. At three thousand feet, a white mushroom of parachute silk billowed below it—somewhere in that chaos, the Japanese pilot had managed to bail out, a tiny, fragile life now hanging between sea and sky.

The fighter plunged on, burning, until it hit the water in a brief, violent splash of fire.

“Time zero-zero forty-six,” Porter said, voice strangely soft. “Frank down.”

Smith didn’t answer. He was looking at the fuel gauge.

Fifteen percent.

A cold, practical corner of his mind started doing math again, rattling numbers over the drumbeat of his pulse.

“Distance to Meuire?” he asked.

“Twelve miles, roughly,” Porter answered. “South-southwest. If you take us in a straight line, we’ll be overhead in about three minutes.”

“That’s what we’ll do, then,” Smith said.

He turned the Black Widow toward home and nudged the throttles back to cruise. This was no time to be dramatic.

The coastline of Mindoro appeared first as a slightly darker smear against the sea. Radar showed it as a thickening, irregular shape, a bright mass against the empty sweep of water returns.

Porter guided him in like a blind man leading another blind man by the elbow.

“Coastline ahead in one minute,” he said. “Meuire Field is inland, about a mile from the beach on this bearing. We’re eight miles out. Fuel… fourteen percent.”

Down below, the airfield was a hive of activity. The sirens had stopped. Word had spread—no bombs tonight. Men emerged from trenches, blinking in the sudden absence of urgency.

Somewhere in the tent city, someone had an ear glued to a field phone, listening to GCI and squadron operations chatter, spreading news in the gossip network that moved faster than official reports.

“He got four of ’em,” someone said. “Four goddamn bombers. And a fighter.”

“Bull,” someone else replied automatically, because news that good needed a second to sink in.

Up near the runway, a line of kerosene lamps still burned, twelve dim dots marking a strip of crushed coral that was just barely long enough for a Black Widow to land on.

Smith descended through two thousand feet. The altimeter needle swept past numbers, the rate-of-climb indicator showing a steady descent. Outside, the darkness was absolute. No moon penetrated the cloud deck. The light from the runway lamps was lost in the void at this distance.

“Eight-Two, Meuire Tower,” the field controller’s voice came on. “We got you on the board. Wind calm. You are cleared to land, runway one-eight. Keep her tight—we still got traffic.”

“Roger, Tower,” Smith replied. “We’re coming in.”

He lowered the gear. There was a reassuring thump and whine as the main wheels and nosewheel locked into place. Three green lights winked on.

He pulled the power back, let the aircraft settle. One thousand feet. Eight hundred. Airspeed 140 knots. Well above the stall speed, but he’d bleed that off in the pattern.

Down below, in a little wooden shack half-buried in sandbags near the runway, a corporal went out to trim one of the kerosene lamps. He cursed as he knocked it over. The flame sputtered, flared, then went out entirely.

A second later, as if some perverse spirit had been waiting, the generator feeding power to the few electric work lights coughed, stuttered, and died.

One by one, like someone snuffing candles with invisible fingers, the line of lamps marking the runway winked out.

In the Black Widow’s cockpit, Smith’s eyes went wide.

“Tower, Eight-Two,” he said sharply. “I’ve just lost your runway lights. Confirm?”

There was confusion on the other end of the radio. Voices, muffled, cursing.

“Eight-Two, Tower. Affirmative,” the controller said finally, sounding more rattled than he would ever admit later. “We just lost ’em. Working on it. Stand by. If you can hold—”

“I can’t hold long,” Smith cut in. “Fuel’s at nine percent.”

Nine percent: about forty-six gallons. At their current consumption, maybe eight minutes. The nearest alternate field, on Leyte, lay ninety miles away—completely out of the question.

He had a choice: land without visual references, or ditch in the ocean somewhere off the coast and hope someone saw where he went down before he disappeared into the drink.

Porter’s voice came over the intercom, reflective, not panicked.

“We’ve got the radar altimeter,” he said. “It’ll give you height above the ground. We know roughly where the runway is from earlier approaches. We could—”

“Land by braille,” Smith said.

“Yeah,” Porter replied. “Turning yourself into a test case wasn’t on the syllabus, but here we are.”

Smith stared into the black. There was literally nothing. His landing lights were off; turning them on might help, or they might blind him, or make him a target for any stray enemy still out there.

He pictured the runway in his mind—a straight white strip by day, coral and dirt packed down, a little narrower than he’d like. He’d landed on it before, with lights. He knew its orientation. He knew the pattern.

He didn’t know where exactly he was relative to it now.

“Phil,” he said slowly, “give me a bearing to the runway. Treat it like a bogey.”

Porter bent over the scope again, shifting the radar scale until the island’s edge and the airfield stood out as a blob. It wasn’t what the radar was designed for, but radar didn’t know what it was supposed to see. It just showed what was there.

“Okay,” Porter said. “Meuire Field is approximately one o’clock, range about five miles. Come right fifteen degrees. Hold altitude at six hundred feet.”

“Six hundred?” Smith repeated.

“In case there are any palm trees taller than we thought,” Porter said.

Smith turned. The Black Widow responded obediently. The amount of trust he was placing in Porter at that moment was absolute and unexamined.

He eased the throttles back further, letting the speed bleed off to 120 knots. Full flaps extended, the aircraft’s nose dropped. The radar altimeter began to tick downward—500 feet above ground level. Four hundred. Three eighty.

“Fuel?” he asked.

“Eight percent,” Porter said. “Maybe six or seven minutes.”

“This’ll be over in two,” Smith said. “One way or the other.”

He settled into a descent, rate about three hundred feet per minute. At this angle, at this speed, he should intersect the ground roughly where the runway was—if his mental picture and Porter’s guidance were right.

The fact that the terrain around Meuire was a chaos of jungle, coral, construction equipment, and half-finished taxiways did not bear thinking about.

He watched the radar altimeter like a man watching his own heartbeat.

Two hundred and fifty feet. Two hundred. One fifty.

Outside the cockpit, there was still nothing but black.

In the back, Porter kept murmuring bearings.

“Good, good. You’re right on the line. Field should be dead ahead in a half-mile. Altitude one-fifty. You’re doing fine, Major.”

Fine. Flying a thirty-two-thousand-pound aircraft toward an unseen ground at night with fuel ticking away like sand in an hourglass.

“One hundred feet,” Smith said, more to himself than to anyone else. He eased the throttles up a hair to arrest the descent, trying to feel for the ground with the wheels.

Seventy-five. Fifty.

Normally, this was where the runway would appear under his nose, a strip of lighter gray in the cockpit windows, lights sliding by in his peripheral vision.

There was nothing.

He pulled back gently on the yoke, raising the nose. The descent rate dropped—two hundred feet per minute, then one fifty.

Twenty-five feet.

“Hold it… hold it…” he whispered, hands firm but not tight.

He felt, as much as heard, the impact as the main wheels met the crushed coral. A thump, a jolt running up the struts into his spine. For a horrible moment, the aircraft bounced, lifted slightly as momentum tried to carry it back into the air.

He fought the urge to shove the nose down. Instead, he eased the yoke forward just a fraction, let the nose settle, feeling for the ground.

The wheels kissed down again, harder this time, but they stayed.

The nosewheel thumped down a second later. The rumble of tires on rough surface replaced the hiss of air over the wings, a different kind of vibration under his feet.

He couldn’t see, but he could feel the plane was on something firm that extended in a straight line.

He brought the throttles to idle and hauled the brakes in. The P-61 shuddered, decelerating—100 knots, 80, 60, 40.

If he had landed short, they would already be cartwheeling through jungle. If he’d landed long, they’d be plowing off the end into a construction pit.

The aircraft rolled to a stop.

Smith’s hands were shaking. He only realized it when he tried to pull them away from the yoke and they didn’t respond the way he expected.

He glanced at the fuel gauge.

Six percent.

Maybe twenty-nine gallons left. Enough to circle the field for three minutes. No more.

“Major,” Porter said softly, “I think we’re down.”

“Yeah,” Smith said hoarsely. “I gathered.”

Outside the canopy, lights flickered into view—flashlights, truck lamps, the bobbing lanterns of ground crew running toward the dark silhouette of the P-61 that had appeared in the middle of a darkened runway like some great black bird.

Someone banged on the side of the fuselage, the cheerful ritual of men welcoming a returning aircraft that could have easily been a fireball somewhere out beyond the surf.

Smith shut down the engines. The twin roars died away, leaving a ringing silence in his ears.

The cockpit suddenly felt very small.

He unbuckled, lifted the canopy, and cool, humid air flooded in. The smells of the jungle, of fuel, of men and wet canvas met him all at once. It felt like walking into a bar from a long tunnel.

He swung a leg over the cockpit rim and climbed down onto the wing. His knees felt rubbery. He almost missed the wing root and had to catch himself on a handhold.

“Easy there, Major,” the crew chief said, stepping up to steady him. “We need you to go do that again tomorrow night.”

Smith managed a tired grin.

“Let’s get through tonight first,” he said.

Porter emerged from his compartment a moment later, face pale under the smudges of sweat and dust, eyes still wide from hours of staring at green phosphor.

They clasped hands awkwardly on the wing, a quick, tight grip between men who knew they had just pulled off something that should have been impossible.

The numbers would come later. For now, it was enough to stand on solid ground and know that they had lived through it.

The debriefing started as they walked toward the operations shack. Intelligence officers descended like vultures—polite, persistent vultures with notebooks.

“What were the times of each intercept?”

“How far north would you estimate the first Betty went in?”

“Can you describe any markings on the fighter?”

Smith answered as best he could, pulling times from memory, guesstimating distances based on speed and countdowns. Porter filled in with radar ranges, altitudes, headings.

Four Betty bombers. One Helen. One Frank. All destroyed. First splash at 23:57. Last at 00:46.

Forty-nine minutes from first kill to last.

Their ammo expenditure: 408 rounds. Their outgoing fuel: all but a sliver.

The intelligence men nodded, scribbling, cross-checking with notes from GCI and from coast watchers who had reported flames on the horizon. By dawn, they’d confirm all the kills—wreckage sighted at sea, positions matching the times and courses Porter had logged.

Someone added the tallies to a board in the squadron tent, where neat little Japanese flags represented victories.

Major Carol C. Smith had come into the night with four kills to his name. By the time he walked back out of the debriefing shack, he had seven.

He was, in that moment, the highest-scoring American night fighter pilot in the Pacific. He had done it in less than twenty-four hours of flying, using an aircraft that itself was only a few months old in the theater.

He didn’t feel like a hero. He felt like a man who had dodged a bullet, several bullets, and was waiting to see where the next one might come from.

After a few hours of fitful sleep on a canvas cot in a tent that smelled of canvas, dust, and too many men, he was back at the flight line.

The sun was high, the jungle buzzing with life. The night’s terrors felt distant in the harsh clarity of daylight, but they were still there, lurking behind the eyes of every man who’d heard flak and sirens.

At 14:30 that afternoon, Smith climbed back into the same P-61. The fuselage still wore the faint streaks of cordite and exhaust from the night before. The ground crew had refueled it, rearmed the cannons, checked the landing gear for damage from the heavy touchdown.

“Thought you might want to take a break, Major,” the crew chief said when he saw Smith approaching.

Smith shrugged.

“Japanese didn’t,” he said. “Recon flights over the field. Somebody’s gotta tell them that party’s over too.”

Porter was already in the back, tightening straps.

“Ready for an easy one?” he called forward, grim humor in his voice. “Daylight, one bandit, no fuel drama? Maybe we come home with ten percent for once.”

“That’ll be the day,” Smith replied.

They took off into a sky as blue and pure as the night had been black. Clouds piled high over the mountains, white columns that would be beautiful in another world.

At fifteen twelve, Porter’s scope picked up a single fast-moving target at twelve thousand feet, heading north.

“Looks like another Frank,” he said. “Recon, maybe. He thinks he’s too fast to get caught.”

Smith climbed, used the P-61’s power and altitude to compensate for the Frank’s speed advantage in level flight. Approaching from above, gravity itself became his ally.

At four hundred yards, with the sun behind him and the Frank’s pilot blissfully unaware, he fired a two-second burst. Forty-eight rounds again.

The fighter’s engine exploded. The aircraft rolled inverted and dived to its death in the sparkling water below.

Seventh kill confirmed.

It was, in some ways, less dramatic than the night’s work. But it mattered. Every enemy aircraft that didn’t get close to Meuire was one less problem for the men on the ground.

On the other side of the war, in a briefing room somewhere in the remnants of the Japanese air command in the Philippines, officers stared at a map littered with markers.

Twelve bombers had taken off the previous night. Eight had returned, scattered and shaken, their crews talking about explosions in the dark; about comrades disappearing from formation; about fire suddenly blooming on the ocean below.

One crew swore they had seen a phantom in the sky—a vague shadow pacing them, then a sudden streak of red light, then nothing.

A fighter pilot, one of the few flying the precious new Ki-84s, had not returned at all.

Someone, somewhere, realized that the Americans had found a way to see in the dark.

Rumors spread among pilots about a big twin-engine aircraft, painted black, that appeared out of nowhere behind you and turned bombers into torches. Some called it a ghost. Others gave it more grudging respect.

They would later learn its name—Black Widow. At the time, it was simply a terror, a hunter whose eyes could see what theirs could not.

The Japanese high command had gambled that darkness would protect their bombers. It had been a logical assumption. For years, night raids had been the best way to slip past Allied fighters.

On December 29th–30th, 1944, that assumption died.

Meuire Field continued to grow. The engineers Smith had protected worked through the next nights and days, laying more planking, extending the runway, building revetments. They cursed the heat, the bugs, the occasional shelling, but they weren’t interrupted by bomb blasts tearing their work apart.

On January 9th, 1945, American forces waded ashore at Lingayen Gulf under the watchful cover of fighters based at Mindoro. P-51s and P-47s roared overhead, their pilots rarely thinking about the unfinished coral strip and the night fighter who had kept it intact weeks earlier.

Wars are built on such invisible moments—the times when something terrible doesn’t happen because someone took a risk in the dark and won.

Smith survived the war. He went home in February 1946, returned to a America that was eager to trade ration cards for refrigerators, foxholes for front lawns. He left the military, found work in the civilian world. He did not write his memoirs. He did not put himself forward for interviews.

His P-61, the machine that had carried him through those nights, continued flying until the war wound down. It was redesignated F-61 in the late 1940s, used for training, then finally scrapped along with hundreds of other Black Widows when jets took over the role of night fighters.

The nose art, the kill markings, the very aircraft that had hunted four bombers in less than an hour—that particular combination of aluminum, steel, paint, and human confidence vanished into salvage yards and smelters.

On paper, his achievements lived on in squadron records, in dry intelligence reports, in lists of confirmed kills.

Four bombers in one night. One heavy bomber and one fighter added for good measure. One more fighter the next afternoon. Seven kills total. Twenty thousand men on the ground who never knew how close they had come to being chalk marks on a planner’s map.

Those men built airfields. Those airfields launched fighters. Those fighters covered landings. Those landings pushed the war closer to its end.

Years later, an older man sitting at a kitchen table somewhere in America might look up at the sound of a prop-driven plane flying overhead and feel something in his chest that he couldn’t quite put into words. Maybe he’d push his chair back, walk over to the window, and glimpse a small civilian aircraft turning lazily in a clear blue sky.

He would know, in the quiet part of his mind, that what he had flown had been bigger, louder, more lethal. But he might also think, with a faint, private satisfaction, that those peaceful planes flying over supermarkets and schoolyards existed partly because, once upon a time, he and a radar operator named Porter had gone up in the dark and told twelve enemy bombers that the night belonged to someone else now.

And somewhere in the Pacific, beneath a few thousand feet of salt water, lay the twisted remnants of four aircraft whose crews never saw their killer coming.

The Japanese who had flown with them might have found it hard to believe that a single unseen foe could pick off four bombers in what must have felt, from their perspective, like no time at all. That disbelief lasted right up until the moment when, one by one, their comrades simply weren’t there anymore.

The Black Widow didn’t care about belief. Radar didn’t care about honor. The night itself didn’t care about which flag fluttered over which strip of sand.

What mattered, in that thin slice of time over Mindoro, was a cramped cockpit, a ticking fuel gauge, the green glow of a scope in the hands of a man who knew how to read it, and a pilot willing to risk everything to make sure that, when dawn came, the only thing falling on Meuire Field was rain.

News

CH2. What Rommel Said When Patton Outsmarted the Desert Fox on His Own Battlefield

What Rommel Said When Patton Outsmarted the Desert Fox on His Own Battlefield The wind carried sand like knives. It…

CH2. When Two B-17s Piggybacked

When Two B-17s Piggybacked On the last day of 1944, the sky over Germany looked deceptively calm. From the cockpit…

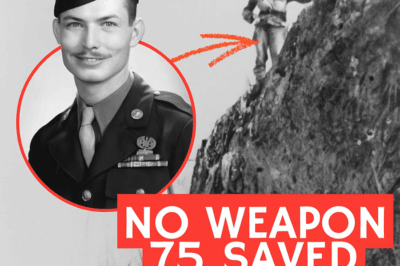

CH2. The Soldier Who Refused to Carry a Weapon — Then Saved 75 Men in One Night

The Soldier Who Refused to Carry a Weapon — Then Saved 75 Men in One Night When Desmond Doss enlisted…

CH2. When A-4 Skyhawks Sank the British

When A-4 Skyhawks Sank the British May 25th, 1982, Argentina’s Revolution Day and the 53rd day of the Falklands War……

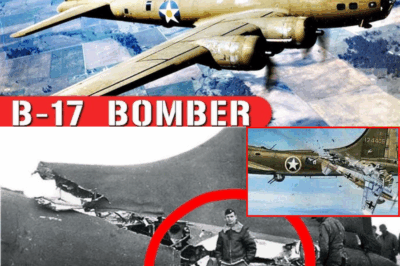

CH2. Was the B-17 Flying Fortress a Legend — or a Flying Coffin? – 124 Disturbing Facts

Was the B-17 Flying Fortress a Legend — or a Flying Coffin? – 124 Disturbing Facts In this powerful World…

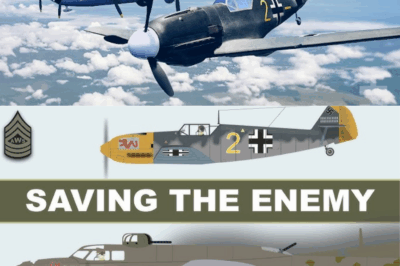

CH2. When a BF-109 spared a B-17

December 20th 1943, a badly shot up B-17 struggled to stay in the air, at the controls Charlie Brown. Passing…

End of content

No more pages to load