I Visited My Second Home To Rent It Out And Found My Son-In-Law There With His Mistress

Part 1

The morning sun poured softly through my bedroom window as I packed a small bag. It had been nearly eight months since I last visited my second home—the one my late husband, Faisal, and I bought when we were still telling time by projects instead of by grief. After he died, I couldn’t bear to stay there. Every room whispered his laugh. Every corner carried the quiet smell of his cologne, the way it clung to sweaters and good news.

My daughter, Asia, had been gently insisting for months. “Ammi, rent it out. Houses are like lungs; they get sick if you don’t let them breathe.” It was the sort of metaphor Faisal would have admired. He was always fond of the ways objects pretended to be human and humans pretended to be brave. So that Saturday morning, I decided to go. The idea of finding a tenant—of choosing someone steady to fill a space that had become a museum—gave me something to focus on.

I made tea. I reviewed the property papers twice even though they hadn’t changed overnight. I counted out the spare keys, polished the brass one with the scuff I’d never fix, and drove through calm streets like a woman headed back to a chapter she wasn’t finished reading.

The garden was exactly as I had left it, only more honest. Jasmine climbed the lattice with the stubbornness of women who refuse to wilt. The grass had gone a little wild around the edges, as if testing whether it could reclaim the stones Faisal had laid with a mason’s pride and a husband’s patience. I smiled faintly—until I saw a sleek black car parked cockily in the driveway.

I hadn’t given anyone the key.

A caretaker? A neighbor? I walked slower. Men’s shoes—polished, expensive—rested by the door like assumptions. My heart began to do a small, useless dance in my chest. I turned the handle gently. It was unlocked. Inside, faint music floated through the air, something soft and romantic that did not belong to dust.

I took a few quiet steps, my heels barely touching the wood. From the living room came a sound that belonged to strangers—intimate laughter, the kind that speaks a language made from inside jokes and borrowed trust.

I turned the corner. Time didn’t stop; it slouched.

Haris—my son-in-law, the same man who called me Ammi and warmed my hands with his when Faisal died—sat on my sofa. His arm draped around a young woman in a dress the color of secrets. She giggled into one of my teacups, floral china I kept wrapped in paper for special guests. His smile was easy. His hand was familiar on a body that was not my daughter’s.

My throat closed. The room darkened at the edges like a film that burns at the reel. I pressed my palm to the cool wall—the one I had painted myself, two coats, too many memories—and walked out before my breath could betray me. The door clicked softly behind me, an apology I didn’t accept.

I leaned against my car in the driveway and cried without making a sound. The jasmine smelled sweet. The word that formed in my mouth tasted like rust.

He had not just betrayed Asia. He had betrayed me. He had brought ugliness into a house built with love and called it rest.

On the drive back, grief sat in the passenger seat pretending to be rage. Under it, something else stirred—cold, deliberate, patient. The beginnings of a plan.

Part 2

I did not tell Asia that night. I made tea with hands that remembered their work and paced under Faisal’s portrait until the quiet asked me its question: “What will you do now, Amira?”

If I told Asia without proof, she might defend him. Love listens poorly when it is reluctant to understand. So I swallowed the truth and made a promise to it in the same breath: “I will carry you until you can carry yourself.”

Asia called me that afternoon, cheerful and unaware. “Ammi, did you go? Haris said he could help with tenants on weekends. He’s so good with people.”

“He rests well,” I said, voice steady and deadpan enough to pass for calm. “I’ll take care of everything myself.”

“Good,” she said. “He’s been working so hard. He deserves a break.”

Break. He had taken one in my home with a stranger’s lipstick ghosting my teacup. I hung up and stared at the ceiling until the plaster gave me permission to move again.

Some women choose fire. I chose frost. Shouting burns fast; documentation freezes clean. Haris thought he was clever. He had not counted on a widow with time and an accountant’s love of receipts.

Samina installed two cameras the next day. “You didn’t tell me it was for this,” she said softly as she screwed the lens into a teapot that would not pour but would tell me everything. The second sat smiling from a picture frame in the study. Every quiet click felt like a stitch sewing up a wound from the inside.

I put a neat advertisement online. “Sunlit two-bedroom near jasmine, available immediately.” I called two local agents and told them, specifically, that my son-in-law would be showing the place because I was caring for a relative. He would feel important and necessary. Men like that find importance intoxicating; they inhale until it erases their caution.

The cameras were very patient. They watched him arrive three days later, set down his keys with the entitlement of a man who thinks nothing he touches belongs to anyone else, and greet the same woman whose laugh I had memorized against my will. He kissed her in the hallway like a teenager and then brewed her tea in my kitchen with my leaves. He smiled like a husband on Sunday morning and pressed his hand into the small of her back like a stranger in a dim bar.

They recorded bank transfers too: small amounts sent from Asia’s account to a new savings account with a name I did not recognize—advertised as “investments,” described over dinner as “opportunities,” siphoned in reality into something like a hotel bill.

I called the bank under a harmless pretense about house paperwork and learned enough to know I could learn more later. I told Mrs. Chou next door that tenants might be arriving, and she said, with the brutal kindness of old women, “He comes with a girl. She wears a perfume that smells like a story that will end badly.”

Each ordinary detail—perfume notes, arrival times, the way he parked under the maple as if the tree itself were an accomplice—became bricks. I built a wall with them not to keep pain out. The pain had already come. I built it to hold it in place long enough for Asia to see it.

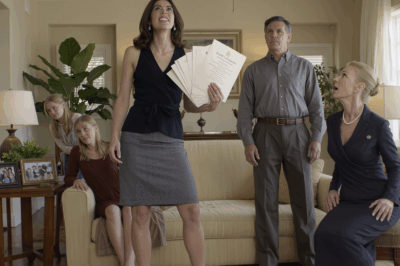

A week later, the envelope was thick and almost weightless. Inside it: a neat stack of printed bank statements, screenshots of transfers with notes (“just until…love you”), dates highlighted; stills from the cameras and a small USB; a summary written in simple nouns and verbs with no adjectives, because truth will not be improved by my heartbreak.

I put the envelope under my pillow that night like a talisman. I slept for five hours in a row for the first time since the jasmine bloomed.

Part 3

We had biryani that night, the kind Asia makes for guests and aching mothers. The table glowed. Haris poured water into my glass with the easy skill of a man who believes attention is absolution.

“Ammi,” Asia said, hand brushing his on the way to the chutney, the kind of unremarkable intimacy that makes betrayal obscene. “Tell us about the tenants.”

“I brought something else,” I said, and when Haris looked up, he saw only the woman he had called Ammi. He did not see the woman who had spent a week being exact.

“Would you put this in the TV?” I asked Asia, passing her the USB. “I want to show you a video.”

At first: a living room. The carpet I chose with Faisal because it hid spills and welcomed feet. Then a woman’s laugh. Then Haris, framed by familiar walls, lips brushing a cheek that did not belong to my daughter.

The room did not break; it was broken already. The air simply caught up.

Asia’s spoon clattered onto the plate. Haris lunged for the remote like a boy who’d been caught stealing and still thought he could pretend his hands were clean. “Asia, it’s not—”

“Not what it looks like?” she asked, so quietly that I almost missed the sharp edge under the softness. “It looks like you are a stranger in my mother’s house.”

I set the second envelope on the table. “There is more,” I said. “Transfers from your account to another one. Notes calling them investments.”

Haris’s face tried on three expressions and none of them fit. He cursed. He pleaded. He called me cruel with a mouth that still smelled like my tea.

Asia lifted the bank statement with hands that had just broken a cinnamon stick and looked at her name on a bad line. The color left her cheeks in a way that made me remember her as a baby, the first time a fever had scared me. She looked at him for a long time and then said one word: “Leave.”

He performed the man who fights for his life, then the boy who begs for grace, then the stranger who insults to wound what he cannot keep. He left with his rage trailing behind him like an untied shoe.

I did not say I told you so because I never had. I had told her nothing. I had only shown her everything. She folded into me and sobbed. I stroked her hair back from her face and whispered the only true thing I had learned since the maple had started dropping leaves, “You saved yourself. I just turned on the light.”

The divorce papers moved quickly with money being a confession where apologies had failed. The transfers became evidence. The recordings became timeline. Asia found a lawyer with a voice that could talk a wall into telling the truth. The attorney had opinions about men who used other people’s houses as hotel rooms and other people’s accounts as savings. Judges do not like their time wasted by pretty stories.

Neighbors stopped saying “how are you?” and started saying “we suspected” and then learned to skip both and just put lunch on the porch. The jasmine kept blooming. The house—my second heart—smelled like sugar and soil and the faint, stubborn perfume of rebirth.

Part 4

Asia moved through grief like a woman who had learned that drowning is not the same as being in water. She started painting again. Canvases leaned against the wall, and the house watched colors return to a life that had been rendered in beige for too long. She did not talk much about Haris except when the lawyer needed her to. She said his name like a lint you remove from a coat before you leave the house.

I finally rented the second home to a quiet couple who liked the jasmine and promised to never rearrange the furniture without asking—the kind of promise that tells you a great deal about how someone was raised. Before they arrived, I aired the rooms. I washed the teacups as if they could feel shame and then told them they didn’t have to. I scrubbed the living room carpet with vinegar and prayer. I opened all the windows and let the house breathe.

After I handed the new tenants the keys, I locked the door and leaned my forehead against it for a moment like a woman eavesdropping on her own heart. The lock clicked—a small sound that felt like a verdict.

Haris tried to contact us. He wrote emails with subject lines that suggested remorse without ever offering any. He left a voicemail for Asia that said “We could try” and a voicemail for me that said “We were family.” I forwarded them both to the lawyer and then deleted them from my soul.

My revenge was not loud. It did not demand applause. It was a precise thing stitched with thread that looks like patience. I prosecuted nothing in a court that had no judge. I arranged evidence until it told the story to the only audience that mattered. I chose dignity over spectacle, proof over performance.

Months later, on a Thursday with ordinary weather, I stood in the rented house’s garden. The jasmine brushed my wrist when I reached to tie it back. Behind me, inside, laughter—new laughter—filled the rooms in a way that did not offend the walls. I touched the top of the garden gate—Faisal’s gate—and for the first time since the day I saw polished shoes beside a door that had belonged to love, I took a breath that did not have to fight for space.

Asia came by with paint on her fingers and smile on her mouth, the kind of smile that says I have met sorrow and it has not made me small. We made tea. We used cups that had never known mockery.

“Ammi,” she said, looking at the jasmine, “It smells like summer and forgiveness.”

“It smells like work,” I said, smiling against the rim of my cup. “Things that grow need tending.”

We didn’t say his name. We didn’t need to. Some people you put down not with a bang but with a quiet refusal to let their footsteps dirty your floors again.

Later, when the sun had started to soften and the tenants’ laughter had dissolved into the hush of evening, I locked the door behind us. The key turned easily.

Some betrayals demand fury. Mine asked for dignity. The house that once held our happiest memories had held a dirty secret. It now held something better: the knowledge that I will not be invited to my own undoing and choose to attend.

We drove home by streets that had learned we can survive ourselves. Asia’s paintings waited on her walls. My kettle waited on my stove. The jasmine behind us shivered in the breeze like a woman shaking off a bad dream. I did not look back because I didn’t need to.

Some homes must be rented to be saved. Some daughters must become quiet storms to be heard. And some mothers learn, after grief and gardens and a teacup turned witness, that revenge can be nothing more than proof arranged gently on a table, a door locked after, and a life rebuilt with hands that remember how to hold and how to let go.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Mom Screamed: “Where Do We Sleep?!” When I Refused to Let My Brother’s Family Move In My Home

My Mom Screamed: “Where Do We Sleep?!” When I Refused to Let My Brother’s Family Move In My Home …

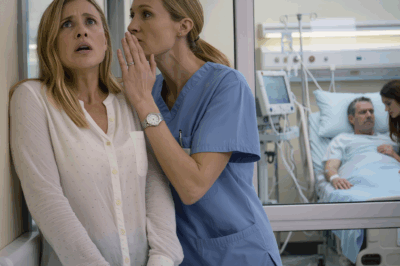

CH2. I Rushed To The ICU For My Husband. A Nurse Stopped Me: “Hide, Wait.” I Froze When I Realized Why…

I Rushed To The ICU For My Husband. A Nurse Stopped Me: “Hide, Wait.” I Froze When I Realized Why……

CH2. My Girlfriend Admitted: ‘I Faked Your Signature to Co-Sign a Car Loan for My Brother. You Can Handle the Cost.’ I Responded: ‘I Understand.’

My Girlfriend Admitted: “I Faked Your Signature to Co-Sign a Car Loan for My Brother. You Can Handle the Cost.”…

CH2. My Mom Changed the Locks and Told Me I Had No Home — So I Took Half the House Legally.

My Mom Changed the Locks and Told Me I Had No Home — So I Took Half the House Legally….

CH2. My Mom Said: ‘Stanford Is for Chelsea, Not You’ — So I Brought Out the Proof in Front of Them…

My Mom Said: ‘Stanford Is for Chelsea, Not You’ — So I Brought Out the Proof in Front of Them……

CH2. My Mom Said “Flights Are $1,450 Each. If You Can’t Afford It, Stay Behind” Then Charged $9,540 On Me

My Mom Said “Flights Are $1,450 Each. If You Can’t Afford It, Stay Behind” Then Charged $9,540 On Me …

End of content

No more pages to load