I Used Sign Language to Help a Deaf Homeless Veteran, I Had No Idea a Four-Star General Was Watching

Part I

The first time I saw him he was shivering outside the base gate, clutching a cardboard sign that read, “Deaf veteran, need help.” Wind scraped along the chain link and snapped at the corners of his jacket—the old army kind, thinned by decades, its color surrendered to weather and time. Soldiers streamed past him without a glance. Engines idled. A horn barked at the checkpoint, impatient and impersonal.

Somewhere behind me a drill sergeant’s voice ricocheted across concrete. The old man just stood there, lips moving soundlessly, eyes searching, hands hovering as if he’d forgotten what to do with them. Then, with a kind of desperate awkwardness, his fingers lifted and shaped the air—slow, halting, as if his body remembered a language he feared had been taken from him. It broke a rule inside me that I hadn’t known was there.

I was not supposed to leave my post. I was not supposed to speak to civilians. I was not supposed to do any of the things that drew attention to a quiet communications private who lived by the manual and disappeared when the door closed.

But something in the way he carried himself—tired yet proud, invisible yet unbroken—struck harder than any command I’d heard through a radio. I took a step. The corporal to my left muttered, “Ignore him, Hayes. We’re not social workers.”

Another step, and I was close enough to read the grief behind his eyes.

Hello, I signed, rusty from years of using ASL only at home. Are you okay?

He froze. Surprise widened his weathered face into something boyish and disbelieving. Then he smiled—one of those slow smiles that travel through a lifetime before they reach the surface—and answered, Thank you. I didn’t think anyone here could understand me.

His name was Robert Keller. Combat engineer, Vietnam era. He’d lost his hearing to artillery and learned to navigate the rest of life by reading faces and hands. After the war he worked construction, loved a woman named Anne, paid bills, mowed lawns, put his head down like good men do. Then life complicated itself. Anne died. Paperwork failed him. An expired ID turned into an expired proof of existence. Every office pushed him onto another chair in another building where another clerk shrugged and asked him to call a number he could not hear.

He’d come to the base hoping the VA liaison could help untangle it all, but the guard at the door only saw an old man mouthing words that didn’t land. So he stayed, because leaving would mean admitting he had no place else to go. I handed him the last heat in my thermos. He signed thank you with both hands, a motion I’d always loved for the way it felt like an embrace.

Can I help you call someone? I asked. He shook his head. No one left to call.

The words landed with more weight than any reprimand ever could. My radio cracked—Hayes, report. You’re off position. Over.—and the reality of what I was doing snapped back like a rubber band. I turned to go. Robert touched my sleeve with two trembling fingers and signed, Thank you for seeing me.

Five signs. Two seconds. A whole life of being unseen tucked between them.

When my shift ended, my commanding officer’s glare could have sanded wood. “What were you doing at the gate?”

“Sir, there was a deaf veteran—”

“Not your problem,” he cut in. “Next time, keep your post.”

I nodded. But the shame wasn’t for breaking a rule. It was for the rule itself.

That night I couldn’t sleep. Memories of my mother’s hands hovered in the dark—her fingers bright with meaning, her eyes steady in a noisy world. She’d been deaf since childhood and had taught me that silence isn’t the hard part. The hard part is when people refuse to slow down. I kept seeing Keller’s sign, the way the letters on “Need help” looked like they’d been written in a shaking car.

By morning I’d decided to walk over to the VA liaison office on my lunch break. Maybe I could ask around, learn what a private is allowed to learn. But when I stepped out of the barracks a black SUV idled at the curb. A staff sergeant handed me an envelope. The official letterhead felt like a warning as my thumb skimmed the seal.

Private Catherine Hayes, report to General H. L. Mason, Command Office, 0900 hours. Confidential.

General Henry L. Mason—the four-star who could make major decisions feel like minor adjustments. I’d seen him only twice, both times on parade fields where he moved like a statue that had learned to breathe. My stomach dropped so fast the rest of me followed.

I walked into his office expecting punishment. The room smelled faintly of leather polish and old paper, a museum of rank: flags, awards, framed photographs in which he was perpetually younger, dirtier, grinning with men in fatigues. One photo sat front and center—Mason with the president, the kind that gets printed on glossy brochures. Another stuck in the corner: a platoon in mud, their smiles edged with exhaustion.

“Private Hayes,” he said, still turned to the window. “Sit.”

I did. My heart made its own percussion in my ears.

“I heard what happened yesterday. The man at the gate.”

“Yes, sir. I know I broke protocol.”

He turned. For a fraction of a second something softened around his mouth before it rearranged itself. “Tell me what you did.”

“He was deaf, sir. No one could understand him. I… I signed. I tried to help.”

“You know ASL?”

“Yes, sir. My mother is deaf.”

He nodded as if he’d been waiting for the answer. “Good. That language saves more than words.”

Silence filled the room. I braced for the reprimand—the long talk about discipline, the short one about consequences. Instead he picked up a folder and slid it across the desk to me.

“I’m reassigning you temporarily. VA liaison office. Report tomorrow morning.”

“Sir, is this punishment?”

“Punishment?” There was almost a smile. “No, Private. Call it an opportunity. You’ll understand soon enough.”

The VA office was a gray building you could drive past a thousand times and swear you’d never seen. Coffee smelled like it had been heated, cooled, and convinced to live again. Files colonized every horizontal surface. The secretary, Mrs. Lawson, looked up over her reading glasses when I introduced myself.

“You’re the one the general sent.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Well. Then you’re our new problem solver.” She handed me a manila folder fat with mystery. The name printed on the tab pulled my breath short.

Keller, Robert L.

“He was here last week,” Lawson said, thumbing at the edges. “Came for benefits. His discharge records are a mess. Some of it’s sealed, and I don’t have clearance to pry. I can’t even tell what code he left under.”

I slid out page after page—redactions like black winter fields, dates that led nowhere, stamps that said Confidential in a voice meant to end conversations. Robert’s early record was clean: Vietnam, combat engineer, two commendations. Then a cliff. No medical. No pension. No discharge code. As if someone had cut off the last chapter of a book and decided the reader didn’t deserve to know what happened to the character they loved.

At 1600, I stepped outside to clear my head and saw him across the road on a bench, jacket collar tucked high, the same cardboard sign folded and resting like a tired bird beside him. He looked up as if he’d felt my eyes.

“Private Hayes?” he signed with a small smile that warmed the face the cold had carved into angles.

“Mr. Keller.” I sat. “How are you holding up?”

“Better today. You?”

“Confused.” I lifted my hands and let them shape what I couldn’t say aloud. “I’ve been looking through your file. Something’s off.”

He hesitated, then: They forgot me.

“No,” I signed, heat rising under my skin. “Someone hid you.”

His eyes widened. The world seemed to tilt toward a place where truth might be dangerous, and I realized I was already walking there.

We spoke for an hour. He told me about the years after the war: the steady work, the small joys, the letters he’d written to offices that wore different names but shared one face. He told me about the long waiting-room afternoons and the way time lived slower in the lives of the forgotten. When dusk slid between the pine trees I offered him a ride to the shelter. He declined with the kind of soft dignity that makes refusal feel like generosity.

“You’ve already done more than anyone else in fifty years,” he signed, then touched my sleeve. “You’re a good soldier. Your mother would be proud.”

“How do you know about my mother?”

“You sign like someone who learned out of love.”

I walked back to the lot swallowing a knot I hadn’t known was there.

The next morning an envelope waited on my desk. Inside, a photograph: two men in jungle fatigues, shoulders smudged with dirt and youth. One was unmistakably Robert. The other—younger, eyes bright, jaw cut from absolute certainty—was General Henry L. Mason.

A note was paper-clipped to the photo, typed neat and spare: Find out what he’s not telling you. —HLM

I stared until the picture blurred. My chest felt hollowed out and braced at the same time. What kind of secret ties a deaf, homeless veteran to a four-star general like a knot too tight to breathe?

The summons came before sunrise the following day. Captain Ror did not take off his reading glasses when I sat down. “You’ve been reassigned to the VA office, correct?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you’ve been seen fraternizing with an unauthorized civilian near the east gate. Same individual loitering last week.”

“Yes, sir. But—”

“No buts, Hayes.” He slammed a file closed with theatrical precision. “You broke protocol, and now you’re meddling in classified personnel records.”

“Sir, with respect—”

“You’re a private, not an investigator. Remember your place.”

I took the reprimand in silence. Ink clicked onto paper. A staple bit down. He dismissed me with a finality that was supposed to teach me something. It did. It taught me how humiliation finds echo chambers in places built on hierarchy. In the mess hall, two corporals snickered, and one asked whether my “old boyfriend at the gate” had written me a love letter in sign.

I stared at the ceiling that night, the reprimand form pinned like a cheap halo above my bed. Failure to maintain post discipline. Somewhere under all that official tone there was a quieter accusation: You cared. That’s not the job.

Two days later Mrs. Lawson slid another envelope across her desk. “Came through interoffice mail,” she said. “No return.”

If you want the truth, check Records Archive, Sublevel 3, file code Bravo-47.

No signature. No initials. It didn’t need them.

Sublevel 3 lived below the base like a rumor. The air it exhaled smelled of dust and erasure. Filing cabinets marched in tight, regimented rows. Lights hummed the way lights do when they’ve been forgotten by daylight.

Bravo-47 was thicker than a manila folder had any right to be. The first page stopped my breath.

Keller, Robert L. Court-martial recommendation, 1971. Charge: Insubordination. Outcome: Record sealed by order of Major H. L. Mason.

The witness statements—what I could see of them—read like someone had tried to un-write a hero. In the gaps between blacked-out lines, a different story flickered: Seven lives saved under fire. A refusal to obey a retreat order. A young officer named Mason present for all of it.

The file ended mid-stride. Subject Keller to be discharged honorably; all records sealed. Case closed.

It wasn’t closed. It was buried.

“Private Hayes,” a voice said behind me. “You have a habit of being where you don’t belong.”

I turned fast. General Mason stood in the doorway with his hands behind his back, posture carved from decades of carrying the invisible.

“Sir,” I stammered. “I—I was just—”

“At ease.” The words were soft. Dust motes wandered between us like lost notes of a song. “So you’ve seen it.”

“Yes, sir.” The paper felt heavy in my hands. “Why seal the file? He was a hero.”

“War isn’t as simple as heroes and villains, Private.” His jaw moved as if he were trying to loosen something that had fused there. “Some stories don’t belong in history books.”

“He saved lives, sir. Yours.”

Something flickered in his eyes, a lightning of the past. “And I’ve spent fifty years trying to forget.”

He turned toward the door. “You want answers, Hayes? Bring him here tomorrow. 0600. Memorial Hall.”

“Sir?”

“Do it.” He didn’t look back. “It’s time.”

The hall at dawn wears solemnity like a suit. Light comes through the high windows in thin, honest lines. The marble keeps secrets the way old churches do—by holding them until they weigh less.

At exactly six, headlights cut the courtyard. Mason stepped out of the same black SUV that had delivered my first summons. The four stars on his shoulder caught the pale light and threw it back like a promise he hadn’t yet decided to keep.

“You came,” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

We walked the corridor edged with bronze plaques that held more names than a human heart can understand. He stopped at a glass case displaying a smoke-charred flag, one corner burned into a curl.

“You’ve read his file.”

“I have.”

“What do you think of him?”

“I think the Army forgot a man who deserved to be remembered.”

“You’re not wrong.” He exhaled, eyes on the flag. “There’s a truth buried in those papers that’s haunted me for half a century. Keller isn’t the only one who lost something that day.”

“Why me?” I asked finally.

He turned, a tired kind of amusement thinning his mouth. “Because you see people the Army stopped seeing long ago.” Then, without warning, his hands lifted, hesitant, like a man remembering a prayer. You did the right thing, he signed—slow, careful.

“My wife was deaf,” he said when he saw my surprise. “I learned enough to hold a conversation. I forgot most of it. Not that.”

“If you can sign, why haven’t you spoken to Keller?”

“Because some conversations require courage I haven’t had in a long time.”

Finding Robert took longer than I wanted and less time than I feared. The shelters didn’t have him. The outreach center shook their heads with regret. He turned up where this had begun—on the bench by the east gate, sign folded like a retired flag.

“There’s someone who wants to see you,” I signed.

His brow furrowed. Who?

“General Mason.”

The smile fell off his face. He looked at his hands the way a man looks at scars he’s tried not to trace. I haven’t heard that name in fifty years.

“He asked to meet tomorrow morning at Memorial Hall.”

Does he remember what he did?

“I think he does.”

His sigh lasted longer than the wind. I used to dream of asking him why. Now I’m not sure I want to know.

We sat in silence, jets drawing thin gray lines across a pale blue sky. When he finally signed, I’ll be there, it felt like the last sentence of a prayer answered too late and just in time.

That night I walked to the chapel. Candles shook in their glass cylinders. I sat at the back and said the first prayer I’d managed in years: Please let tomorrow bring peace, not more pain.

At first light we stood at the gates. Robert’s posture had changed. He looked the same, but he wore a steadiness I hadn’t yet seen on him, the kind that comes when a man decides he’ll meet his past standing up. The guard recognized me and waved us through. Mason waited inside, cap tucked beneath his arm.

“You may observe,” he told me. “No interruptions.”

The two men regarded each other from a distance that had nothing to do with space. Finally Mason spoke, his voice the careful weight of a man trying to place something fragile on a high shelf.

“You haven’t changed much, Captain Keller.”

“It’s Robert now,” the old man signed, sharp and controlled. “The Army took the title when it took everything else.”

Mason flinched so slightly it almost wasn’t there. “It’s time to finish this the right way.” He looked at me. “Tomorrow, first light. Bring every piece of Keller’s record to my office. Everything—commendations, discharge, sealed documents.”

“Yes, sir.”

His eyes returned to Robert. They rested there as if they’d been holding themselves up for too long.

Outside, Robert signed, Do you trust him?

“I’m not sure,” I answered honestly. “But I think he’s ready to tell the truth.”

He nodded once. Then tomorrow the war ends.

I didn’t know which war he meant.

Part II

At dawn the base wore a thin scarf of fog, the parade ground bleached to a blank page. I carried Keller’s file pressed flat against my chest like I could keep it from aging by holding it warm. The guards at the command wing stepped aside as if they’d been told to behave like furniture. Mason’s secretary ushered me in.

“You brought it,” he said, still turned to the window. He wore no jacket, just a crisp shirt with sleeves rolled up, veins like map lines along his forearms. Two coffee cups stood on his desk as if they’d argued about who deserved to be touched.

“Yes, sir.” I set the folder down.

He opened it and paged through with a measured hand until he reached the sheet that carried his younger self’s signature. His thumb stilled. “Fifty-two years,” he murmured. “That’s how long this piece of paper has kept me awake.”

“Sir,” I said, because silence had grown too heavy, “why did you seal it?”

He looked at me and for once didn’t try to be a general. “Because I was a coward.”

The word vibrated in the air like a struck string.

“You’ve earned the truth,” he said, gesturing to a chair. “You and Keller both.”

He told me about 1971 and a place called Hill 304 near the Cambodian border where radio chatter thinned into static and orders traveled slower than shrapnel. He was twenty-four, a lieutenant who believed in the chain of command the way children believe in gravity. Keller was a captain with eyes that measured risk like a carpenter—quick, precise, with care for what might break.

When the shelling started, command radioed a retreat, a cold order from a safe distance. The platoon had seven wounded. The comms were stuttering. The ground was trying to swallow them. Keller shook his head as if he could dislodge an absurdity. “We don’t leave our men,” he’d said. “We die with them before we abandon them.”

He went back into the crater. Carried one man out. Then another. Then another. Mason followed twice, lungs burned, ears ringing, the kind of fear that tastes like copper scratching down his throat. The third time, he didn’t follow. He told himself he needed to coordinate. He told himself he had to manage the perimeter. He told himself what men tell themselves when they are negotiating with their own courage.

When Keller came up the last time, he was half-deaf and bleeding, hauling a kid whose leg hung too loosely from his hip. That was when the air strike landed where it shouldn’t have. Keller threw his body over the wounded soldier. The blast chewed up his hearing and spit it out into silence.

After the dust and triage and inventory of lives and limbs, command wanted a neat story. They opened a manual and pointed to the retreat order and the disobedience that had saved seven men. They needed someone to bear the weight of their mistake. They chose the man who had refused to obey.

“I could have stopped it,” Mason said, his voice level in a way that made it worse. “I was the witness who mattered. I told myself if I kept my record clean, I could fix things later. But power doesn’t heal guilt, Private. It preserves it.”

I stared long at his hands because looking at his face felt like scraping an old wound. “He doesn’t know,” I said.

“He will today.”

“Why me?” I asked one more time.

“Because you were the first person to look at him like a human being in half a century,” he said without flinching. “That’s more authority than these stars have given me in a long time.”

“Bring him to Memorial Hall,” he added, closing the folder with care that felt like apology. “0600.”

When I found Robert waiting on the bench by the gate, his hair was combed and his jacket buttoned as if he’d gathered every small dignity he could carry. We walked in a silence that didn’t scratch. The hall met us with stained glass light and the particular hush that asks people to lower their voices even when they’re alone.

“Keller,” Mason said when we entered.

“General,” Robert signed, his chin raised a fraction of an inch.

Mason’s hands lifted, awkward but committed: I owe you the truth.

I stood near enough to translate if the words needed repair, but most of what traveled between them didn’t require hands or lips. It moved along a wire stretched across decades of regret. Mason confessed: the retreat order; the rescue; the signatures; the decision to survive his career instead of his conscience. “I betrayed you to save myself,” he said, and his voice broke for the first time in his telling.

You had power and I had nothing, Robert signed slowly, as if each word weighed enough to anchor him. And you let them take my name.

I know, Mason said.

You could have spoken. One word.

I know.

Why now?

Because she reminded me what honor looks like.

He glanced at me, and I felt heat rise to my cheekbones that had nothing to do with embarrassment and everything to do with the sudden weight of being watched by history.

Mason squared his shoulders, the movement a practiced choreography of assumption and responsibility. “Private Hayes,” he said, and I stood straighter. “Take this file to Records Command. Restore every commendation. Reinstate his benefits. Effective immediately.”

“Yes, sir.”

He turned back to Robert. “Captain Robert L. Keller, by the authority of my office, your name will be returned to the rolls of honor.” He lifted his hand and finally gave the man the salute he’d owed him for half a century.

Robert hesitated, then returned it with fingers that trembled and didn’t break.

The next morning the spill of rumor filled the base faster than daylight. The memorial hall didn’t hold crowds so much as it gathered witnesses. A small knot of officers formed along the back. A few veterans from the outreach center stood with their hats in their hands. Mrs. Lawson sat in the second row wearing her good blouse. I could feel the room register the strangeness of seeing a four-star general behind a modest podium with a file folder clutched like a confession.

“Not all wars end when the shooting stops,” Mason began. “Fifty-two years ago, on Hill 304, an act of heroism was rewritten as an act of defiance. Today, that ends.”

He called me forward to carry the restored record—a stack that suddenly felt heavier than its paper. He opened it and pinned a Silver Star to Robert’s borrowed blazer, the metal catching light in a way that made the room feel like it had swallowed a sunrise. “For gallantry and selfless courage under fire,” he said, voice roughened by something grief adjacent.

Robert signed, You didn’t have to do this.

Mason answered aloud and in air, Yes. I did.

Then he pulled his own Distinguished Service Cross from his uniform and set it on the podium with a soft sound of metal meeting wood. “This was awarded to me after Hill 304,” he said. “It belongs to him.”

A ripple of shock slid through the room. Robert shook his head. No. That’s yours.

It was yours first, Mason insisted.

Something in the room knelt. They embraced, and applause rose, hesitant at first, then wider, a low wave that broke against the marble and receded without taking anything it hadn’t been invited to.

“I am submitting my resignation,” Mason said when the room quieted, and you could feel everyone forget to act surprised. “A man who spent decades hiding the truth has no business commanding others.”

Don’t, Robert signed, his hands moving quick with a different kind of fear.

“It isn’t punishment,” Mason said, a small smile crossing his face like weather. “It’s peace.”

Then he looked at me. “Private Hayes,” he said, steadier now, “you showed more courage at a gate than I did in a war zone. We need soldiers who remember honor is not written in reports but in actions. You are reassigned as veterans liaison to the new outreach division. Captain Keller has agreed to advise.”

Promoted by compassion. It felt like a phrase you should never say aloud if you wanted the world to treat it as sacred.

That evening the flag went down in a light so red it made silhouettes look like cutouts. The general’s SUV drove away without ceremony. Robert and I sat on the memorial steps, letting quiet tell us what words couldn’t. He looked toward the road with an expression that held both terror and relief.

“He carried it all these years,” I said.

“So did I,” he answered.

“What’s revenge?” I asked, the question arriving with no set destination.

He smiled without showing teeth. “Making the truth impossible to ignore.”

“Then we won.”

He shook his head. “We didn’t win, Private. We came home.”

The bench outside the east gate was empty the next morning. The cardboard sign was gone, and in its place the air felt unexpectedly clean, like the base itself had taken one good breath.

Part III

Six weeks reshaped the base the way spring reshapes a winter-burned field. The hard edges softened. The outreach office—once an afterthought—grew a spine and a doorbell and a brass plate that read Veterans Accessibility & Honor Liaison. Someone decided we needed a slogan. Robert rejected six that sounded like refrigerator magnets before writing one on a napkin: Honor isn’t given. It’s remembered.

We put the napkin in a frame.

The program started the way better things usually start: with small acts that refused to apologize for being small. We trained staff to sign greetings and to slow their mouths when they spoke so eyes could help ears along. We reprinted forms in font sizes you didn’t need a prayer to read. We added a text line to the main office phone number. We leaned on local housing nonprofits until they let the weight of our insistence tip their lists in the direction of men and women who had been waiting without language.

Robert became the loudest quiet person in the building. Hearing loss had made him expert at paying attention, and attention is both a balm and a weapon. He noticed who flinched when someone signed. He noticed who slowed down. He granted praise like a spare kind of currency and spent it carefully until the staff began to hoard it for the right reasons. When he met new veterans he did not ask them to tell him their story right away. He asked whether they wanted coffee first or water. He asked whether they wanted light or shade. He asked whether the chair was comfortable and would move it without comment if it wasn’t.

The day the base reopened the parade grounds for a formal ceremony, the air smelled faintly of cut grass and brass polish. Families filled the folding chairs. Reporters trotted by with lenses like second eyes. The band polished its last sustained note. The base commander dipped his head to the microphone and spoke about courage of conscience. He named Robert. He named Hill 304. The applause clapped through ribs and settled there.

The interview afterward found its way onto the evening news. The reporter asked what forgiveness felt like, and Robert replied through an interpreter, “Like taking off a uniform that was too heavy for too many years.” Mason, standing a careful distance away like a man who wants to honor a boundary, said, “And realizing you were the one who should have carried the weight all along.”

Later, when the lights were down and the microphones were stowed, I brought Robert back to the new office to show him the plaque by the door. He touched the edges of the letters, a habit he’d developed after a life of reading with his eyes and his fingertips. “You started this,” he signed.

“Sir, I just said hello.”

“Exactly.”

By autumn the program had helped secure housing for fifty veterans. By winter we’d doubled that and then stopped counting because making a tally started to feel like a way of telling ourselves a story we were already living. The office had learned to hold both speed and slowness—the speed that keeps things from getting lost again, the slowness that lets someone breathe.

Even the base changed in small ways. In the chow line, I watched a private tap the shoulder of a new recruit who’d missed his number being called and point to the tray with a gesture that translated into any language: your turn. A sergeant I’d never spoken to before stopped me outside the gym and shaped his hands roughly into thank you, and we both laughed at how wrong his sign looked and how right it was anyway.

Robert visited the chapel more than he admitted. I found him there sometimes, sitting in the back row where I’d once prayed to keep pain out of the day. He would close his eyes and hold his hands still in his lap, the quiet a comfortable coat he put on for a while. One time I asked him what he was praying for. He opened his eyes and signed, I don’t ask. I remember.

At Thanksgiving, we invited a dozen veterans who had no family nearby to the office. We set folding tables end to end, covered them with paper tablecloths and markers, and asked everyone to write the name of someone they missed. The table became a map of memory. There were the names of men who hadn’t survived and the names of mothers and dogs. There was a woman named Eileen who had taught a corporal to bake bread. There was a first-grade teacher. A barber. A baseball coach. Robert wrote Anne, and beneath it, in tiny letters, I still love you.

After dessert I caught him studying the window as if it were a horizon you could reach if you squinted. He signed, I used to dream lessons where I could hear. Then he laughed at himself, a small breath that softens a confession. Now I dream of rooms where everyone listens.

I told him I used to dream of being invisible because it felt like safety. He shook his head. Sometimes safety is just an empty room with the lights off, he signed. Better to build a room where people can see each other and not flinch.

General Mason kept his promise to leave quietly. On his last morning, I found a letter on my desk written in a hand steadier than I would have expected. Hayes, you reminded me that the stars on my shoulder mean nothing if I can’t look a man I wronged in the eye. Take care of him. Take care of them all. —HLM. No rank. No elaborate farewell. Just initials like a handshake.

Every Friday Robert and I walked to the east gate. The bench had been removed and replaced with a small stone cut low to the ground so no one would trip over it. It read: To the ones who were unseen, you are seen now. He would set a single white lily against the stone and rest his palm on the cool face of it for a long second. I brought my younger brother, Danny, some mornings. He’d taught me that silence could be a country where you learn the language of patience. He and Robert signed like friends who’d decided talking could wait until they were done laughing.

Pain still found us. Nothing you mend stays mended forever; it needs tending. We met a Marine who’d lost his hearing after an IED and had learned to listen with bone conduction through his teeth, a science trick that felt like magic until he told us how loud loneliness is when no one hears it. We met a woman who signed only with her left hand because the right one shook when she remembered things she didn’t want to remember. We met a man who pretended to understand rather than ask people to repeat themselves, his nod a mask that had hardened into a face. Some days we sent everyone home with the right paperwork and felt like heroes. Some days we built nothing but a table for someone to put their head on while they cried.

I learned to stop apologizing for the times I couldn’t fix it right away. I learned to bring my palms up and say, with my hands and my face, I’m here. We’ll get there. I learned to move my mouth slowly, to put my feet where someone else’s fear couldn’t trip over them.

One afternoon a corporal—the same one who had told me we weren’t social workers—knocked on the office door as if the hinge might object to being used.

“You busy?” he asked.

“We’re always busy,” I said, “but we can stop.”

He looked at Robert, then at me, and attempted a sign that might generously be interpreted as thank you but also could have been the beginning of a bird. We both smiled. He tried again, corrected his thumb, and got close enough to make sense. His ears burned red, but he kept going.

“I had a guy in my unit,” he said. “Afghanistan. He lost his hearing. I… I didn’t know how to talk to him. Wish I’d known this then.”

“Know it now,” Robert signed.

“You can show me more signs?” the corporal asked, to me but also to the air.

“Pull up a chair,” I said.

The base historian visited too. She brought copies of redacted records that were now un-redacted, the black bars lifted like heavy curtains. She told us the file had already started to reassemble itself in official archives: Keller, Robert L., Captain. Rescue of seven soldiers under fire. Commendations restored. Discharge: honorable. She smiled and added, “We don’t erase people here.”

I believed her and also kept my skepticism fed and watered, because change needs both faith and vigilance.

Winter turned a corner into a softer season. We balanced budgets and arguments with equal parts patience and stubbornness. My rank changed: Private to Specialist to Sergeant. The promotion felt less like climbing and more like being handed a different toolbox. I used it to pry open doors, to fix squeaky hinges, to hang a welcome sign outside offices that once looked like closed mouths.

Some nights I walked the base alone, past the memorial and the chapel and the parade ground where so much had shifted without anything visible moving. I thought about Robert asleep in his small apartment by then, a place furnished with thrift-store pride: a couch that knew how to forgive, a table with one leg held steady by a folded magazine, a plant that was somehow still alive. I thought about General Mason somewhere not on base, perhaps wearing the unfamiliar shape of a civilian morning. I wondered if the quiet he had sought had finally been kind to him.

I wondered if my mother could see me—the me who had stopped trying to disappear and started trying to stay.

Part IV

A year passed. The bench at the east gate had become a waypoint. New recruits were told that if they lost their bearings, they could look for the small stone and the wide sky above it and remember what the place was for. The outreach office had helped more than two hundred veterans find housing, work, or a human being who could answer a complicated question without turning it into a dead end. We had measured our days not in victories but in conversations we refused to shorten.

I kept thinking about the beginning—the cold wind, the cardboard sign, the way Robert’s eyes had looked for a landing. Stories are supposed to arc. Lives don’t always obey narrative, but in the office I started to see arcs anyway—small ones, like a private who learned to sign good morning without making it look like he was shooing a fly, or large ones, like a former sergeant who took a job at a hardware store that installed a doorbell with a flashing light because she asked and then told her manager it was legal and decent.

One afternoon an email arrived from a major in Personnel Command requesting my presence at a panel about inclusive readiness training. I wore my cleanest uniform and packed extra pens, because forgetting a pen at a meeting where people use acronyms like nails in a fence can leave you with splinters. At the panel, officers talked about readiness as if it were a number, and I raised my hand and told them readiness is also a verb. It is the action of preparing to take care of the person to your left and right, including the one who needs you to repeat yourself and the one who needs you to stop yelling long enough to understand.

Afterward, a captain approached with a cane and a smile. “My wife taught me to sign,” he said, hands wobbling through a sentence that resolved into sense. “We forget that language is a piece of equipment.”

On the anniversary of the ceremony, the base commander asked if we would say a few words at a small gathering—no press, just people who had work to do and hearts that had room for more. Robert stood at the front and waited until everyone’s attention had adjusted to silence. Then he signed, slowly and with intention, a speech that an interpreter rendered in a voice steady as a drumbeat.

“I spent years thinking I had been erased,” he said through the interpreter. “But I learned it is possible to be seen again. Not by miracle. By work. By hands. By someone who decided that rules are tools and tools are meant to build, not bury.”

He looked at me then and nodded a thank you he didn’t need to sign. I felt the room look my way, and for once I didn’t flinch. I stepped forward and spoke not as a communications specialist but as a woman whose life had changed because she’d broken a small rule.

“I was invisible by choice,” I said. “Until it started to feel like cowardice. I didn’t learn that in a manual. I learned it at a gate, in the cold.”

After the gathering, I walked with Robert to the stone. He placed the white lily there, then rested his palm against the carved letters. A bird hopped ridiculous and fearless near our boots, and the world felt briefly like it had lowered its voice in deference to something quiet and holy.

On the way back, a teenager in civilian clothes stood outside the fence, eyes red and furious, phone in his hand like a flare he wasn’t ready to light. He watched the guardhouse as if willing the door to turn into his father, who was probably somewhere downrange doing a job that steals sleep. When he saw us, he straightened, pretending to be taller than his fear.

“You okay?” I asked.

He shrugged the shrug of someone who has arranged his face so he won’t need to explain it.

Robert raised his hands and signed hello in a way that looks like a small wave and a blessing. The boy frowned, then tried the shape with his own clumsy fingers. Robert added you okay? The boy’s mouth lifted just at the corners. He signed back, not really, and my throat tightened with the surprise and relief of understanding passing between strangers.

We stood with him until his breathing slowed. He told us, eventually, that his father hated video calls because the noise at the base made it hard to hear and made him feel like he was failing as a father and a soldier at the same time. We taught the boy to move his lips slowly, to point with his eyebrows, to write what mattered and show it to the screen. I wrote out the number of the family support office and the hours when the line was answered by a person and not a machine.

When we left, the boy signed thank you, his hands awkward and honest. Robert grinned and signed you’re welcome with a flourish meant to make the boy laugh. He did—the quick kind that escapes before you’ve decided whether you’re allowed to be okay.

On the drive back to the office, Robert tapped the windshield twice with his knuckles. “Superstition?” I asked.

He shook his head and signed, Habit. Used to do it before convoy rolled. Still do when I want a promise from the road.

“What promise did you ask for?”

That we keep going, he signed.

We did. Through another winter, another spring. Through budget meetings that felt like trench warfare and victories that arrived like care packages. Through a grief group where men and women took numbers to speak and then tore up the numbers and decided to talk in the order their hands rose. Through a Christmas morning at the shelter when we handed out socks, which are better than presents that expect stories in return.

Somewhere in that stretch of days and doing, I realized the story had found its ending—not the kind that shuts the book, but the kind that lets the book rest open on the table because you’re going to need it again.

It came on a Wednesday in early summer, the air high with heat, cicadas tuning the afternoon. I walked to the east gate alone. The stone sat quiet, its inscription catching the sun. I placed my palm on it the way Robert had taught me and felt the cool press of memory. The base beyond the fence hummed with the day’s importantness—reveille echoing from some practice ground, a truck backfiring, a cadence line traveling like a braid through air.

I thought about that first morning—the cardboard sign; the way the corporal had told me not to be a social worker; how the world had narrowed to a man’s hands asking to be heard. I thought about Mason’s letter and the day he lifted his hand and returned a salute that had been owed for half a century. I thought about my mother, who had taught me that language can be a shelter and a bridge and a gentle hand on a shoulder.

I signed hello to the empty air, feeling only slightly foolish, and then I signed thank you to no one in particular and everyone at once. For the work. For the weight. For the fact that honor, when it finally arrives in a room, does not shout. It stands in the doorway and waits until you’re ready to face it.

People ask sometimes how this started. I tell them it began with a soldier who broke a small rule, an old man who kept standing at a gate where he could be seen, and a general who decided that confession was the last order he owed to the truth. It began with hands and eyes and the decision to stop pretending that protocol is more sacred than people.

If you ever see someone standing alone where the world has decided not to listen, say hello. Even if you have to use your hands. Especially then. Because restoration is a kind of victory that doesn’t need an enemy, and honor is a living thing—it requires feeding, and it grows best when you share it.

I raised my hand to my brow as the flag lifted above the parade ground. The gesture felt different now, anchored to more than muscle memory. “For the ones we forgot,” I whispered, and the words didn’t taste like regret anymore. They tasted like a promise kept.

Then I turned and walked back toward the office where Robert would already be early, where a pot of coffee would be too strong on purpose, where the door would open to anyone who needed a table, a chair, a form, a map, a quiet, a listening face, or simply a pair of hands willing to bridge the distance between a human heart and the help it deserves.

And that is how the war ended for us—not with surrender, not with victory parades—but with the unremarkable, relentless work of choosing to hear.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Mom Screamed: “Where Do We Sleep?!” When I Refused to Let My Brother’s Family Move In My Home

My Mom Screamed: “Where Do We Sleep?!” When I Refused to Let My Brother’s Family Move In My Home …

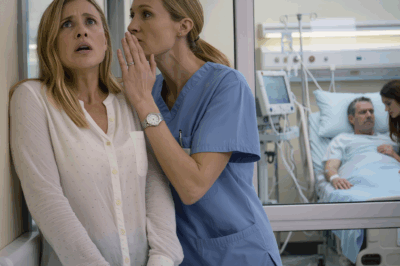

CH2. I Rushed To The ICU For My Husband. A Nurse Stopped Me: “Hide, Wait.” I Froze When I Realized Why…

I Rushed To The ICU For My Husband. A Nurse Stopped Me: “Hide, Wait.” I Froze When I Realized Why……

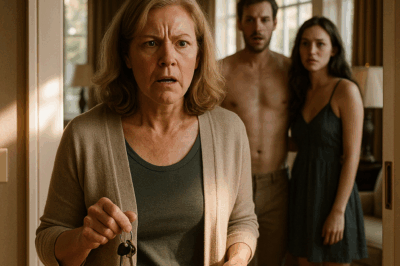

CH2. I Visited My Second Home To Rent It Out And Found My Son-In-Law There With His Mistress

I Visited My Second Home To Rent It Out And Found My Son-In-Law There With His Mistress Part 1 The…

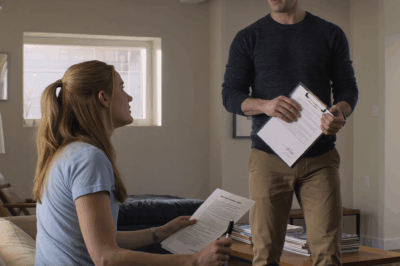

CH2. My Girlfriend Admitted: ‘I Faked Your Signature to Co-Sign a Car Loan for My Brother. You Can Handle the Cost.’ I Responded: ‘I Understand.’

My Girlfriend Admitted: “I Faked Your Signature to Co-Sign a Car Loan for My Brother. You Can Handle the Cost.”…

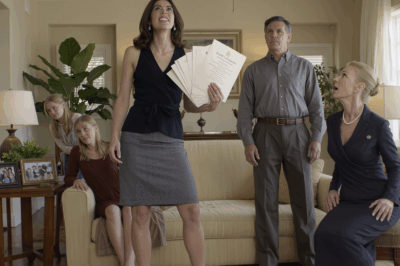

CH2. My Mom Changed the Locks and Told Me I Had No Home — So I Took Half the House Legally.

My Mom Changed the Locks and Told Me I Had No Home — So I Took Half the House Legally….

CH2. My Mom Said: ‘Stanford Is for Chelsea, Not You’ — So I Brought Out the Proof in Front of Them…

My Mom Said: ‘Stanford Is for Chelsea, Not You’ — So I Brought Out the Proof in Front of Them……

End of content

No more pages to load