I Thought They Were Just Refugees — Until My General Said, “Meet My Wife.”

Part I — The Stop

The wind crawled straight through the seams of my parka and bit bone. Eighteen degrees on the thermometer, colder on the road—cold enough to make your breath feel like a mistake. Sleet stung like thrown gravel. The convoy moved on black-iced asphalt the way a tired animal moves—reluctant, obedient.

Seventy miles of humanitarian escort. Trucks groaning under blankets, antibiotics, powdered milk, sterile gauze. Marines in every cab pretending the cold was just another problem we could write an order against. We’d been told twice over the radio: no stops. Keep the convoy moving. Bandit activity. Fuel. Daylight.

I knew all of it. I said all of it. I was Captain Morgan Hayes, United States Marine Corps, under a NATO tasking, and my voice had already worn the words smooth.

But then I saw them. A woman and a child standing like ghosts at the edge of a broken fence line. The boy wore a coat meant for someone two winters older; the woman’s scarf was frozen to itself in a stiff twist. They weren’t waving. They weren’t begging. They were still. Still the way people get when they’ve already spent their last currency on trying.

“Ma’am, we can’t stop,” Corporal Jenkins said, his breath pitching steam into the Humvee cab.

The radio crackled: Convoy 17, status. Report by checkpoint Charlie. No deviations.

I touched the side of my helmet with one finger to quiet the chatter I could control. The other chatter—the one that had been living under my ribs since we arrived in Poland, counting faces and feet and fuel and forgetting to count grace—I couldn’t shut off.

“Pull over,” I said.

“Captain—with respect—”

“Pull. Over.”

The Humvee’s tires snarled at the ice and then quit arguing. I stepped out and the cold landed like a shove. It’d been snowing long enough to erase the road’s edges. Each boot crunch sounded too loud to be safe and too quiet to be enough. I walked toward them with my last MRE in my hand, stupidly aware of the way my own breath fogged the air.

The woman tried to speak—lips chapped and barely moving. English had never been hers. Hunger had taken the rest. She pointed to the boy, then to her stomach, the universal semaphore of need. I tore open the packet and placed the steaming pouch into the boy’s hands. “Eat this,” I said, softly, because tone sometimes translates where words don’t. He didn’t move until his mother nodded once, a sovereign granting her child permission to obey a stranger.

Behind me, Jenkins hissed, “Captain. We are sitting ducks.”

“I know,” I said. “One more minute.”

The woman’s fingers found mine—bare skin on bare skin—shockingly cold, trembling, but steady in the way only mothers are when the worst has already introduced itself and refused to leave. She didn’t say thank you. Her eyes did something larger. Recognition, maybe. The way one human says to another, I remember this kind of world. Thank you for bringing it back.

I fumbled my glove back on. “Stay to the treeline,” I told her, hoping tone made up for language and that the thin strip of woods could offer anything like cover in this geography of hunger.

I waved Jenkins forward. The Humvee coughed, then climbed back into its part in the convoy’s story. Snow took the two small figures back into itself as if to hide them from the sky.

Back at camp, I paid for the stop with jokes. Phelps called me Mother Teresa for a day. Jenkins filed his report and didn’t mention the sixty seconds that could’ve gotten us chewed out. Lieutenant Ortega pulled me aside. “Standing orders are standing orders, Captain,” he said, low, because he is decent. “You want to get yourself reassigned to a desk in Ramstein?”

“If they ask,” I said, “I’ll take it.”

That night, the wind bullied the tent canvas with both hands. I lay awake listening to heaters clatter and the ghost of my mother telling me to bring a scarf. Every time my eyes shut, I saw those two small, still shapes and felt that nod in my palm like a medal I hadn’t earned.

Two days later, our names appeared on a list.

Part II — The Question

“Convoy 17, report to headquarters tomorrow, 0800. Investigation into protocol deviations.”

I ironed my uniform until the creases could cut paper. I polished my boots. I checked the small rack of ribbons that tell strangers where you’ve been and what your luck looks like. I rehearsed blunt sentences in my head. Sir, I couldn’t leave a child to freeze. There are core values that outrank commandments—honor, courage, commitment—and I’d decided to use them as my ammunition.

Headquarters was a Polish administrative block with NATO’s lungs grafted into it. Radiators clanked like they were coughing up old ghosts; the hallway smelled of diesel and burned coffee. My bootsteps sounded like guilt. A lieutenant with paper-thin hands waved me down a corridor.

“The general appreciates punctuality,” he said.

“He also appreciates clarity, I hope,” I said. My voice felt like a tin cup.

“Captain Morgan Hayes, sir,” he announced, and a steadier voice from inside—older than I wanted it to be—said, “Send her in.”

Major General Witmann was spare and tall, mid-fifties, presence without theatrics. Maps on the wall, a space heater humming to itself, a desk stripped of ornament. His secretary had left two mugs and a pot that smelled like it remembered coffee from a better life.

“At ease, Captain,” he said. “Sit.”

He flipped open a folder that contained my last month like evidence. “Convoy 17. Route Delta Kilo. You stopped for civilians.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You’re aware that’s a direct violation of protocol.”

“Yes, sir.”

He watched me the way a decent surgeon watches a patient before deciding whether to cut. “Why?”

I could have said reconnaissance error. I could have said visibility. I could have lied borrowed sense. Layered misdirection over motive the way frost hides dirt. Instead: “There was a woman and a child. They were freezing. I gave them my last pack and we moved. Less than a minute. My team was alert. No harm came to anyone on the convoy because I did my job faster than the order could punish me.”

He leaned back. His clasped hands looked like they recognized what ice can do to a person’s knuckles. “You jeopardized nothing,” he said finally, softly, and it sounded like he was testing the sentence on his own mouth. “You sound like I did twenty years ago.”

That startled me more than a reprimand would have.

“Afghanistan,” he said. “Winter we still don’t like to say out loud. One of my men gave a pair of gloves to a boy with eyes like—” he waved his hand, unwilling to name grief in front of a junior—“lost two fingers that night. He called it a fair trade.”

He made a note in my file. He closed the folder. “You won’t be punished, Captain. But be careful what you decide heroism looks like. It rarely looks clean.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And one more thing.” He picked up a pen again. “Where exactly did you stop?”

“East fence line,” I said, “two klicks past checkpoint Charlie.” I didn’t ask why he needed exact coordinates to file what he’d already decided to forgive. The way he wrote it down made something in my ribs open like a door.

“Thank you,” he said. “Dismissed.”

I walked out into the cold feeling both lighter and more unsettled. Jenkins waited by the trucks. “Well?” he asked. He blew steam into cupped hands like a magician trying to disappear.

“He asked where I stopped.”

“That’s weird.”

“Yeah.”

Two mornings passed like they always do in war: coffee that tastes like regret, fuel reports, inventory reconciling with actual. And then an email arrived with the subject line nobody in a cold country wants to see: Distinguished Visitors: Security Heightened.

I didn’t care. When I saw my name on the morning roster again—Report Headquarters 0900—I cared.

Jenkins stood in the doorway of my tent while I tightened my collar. “If they pin you to a lectern for a cautionary tale,” he said, “I’m telling everyone you cried.”

“If they do anything that involves a pin,” I said, “I’m telling everyone you smiled.”

He gave me the kind of grin men give when they’ve learned to survive by making other men feel safer. “You’re our kind of Captain, ma’am,” he said. “Just try not to earn a sainthood. The paperwork is insane.”

In the headquarters corridor, I heard a sound that didn’t belong: a child laughing. High, soft, set wrong in a building where maps are more honest than dreams.

“Captain Hayes?” the general’s voice called from inside. “Come in.”

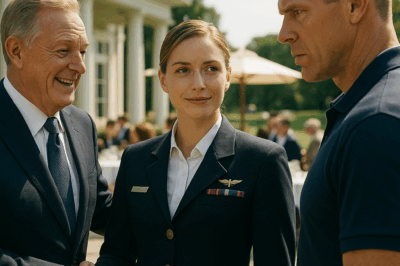

The maps were gone. A NATO banner hung where Afghanistan used to stare. There was a coffee pot that didn’t look tired. And there—beside Major General Witmann—stood a woman with a scarf wrapped neatly around her throat and a boy tucked under her coat, half shy, half alive.

His eyes were the same. Her nod was almost the same. I saluted because if I didn’t, my hands would have reminded me they could shake.

“At ease, Captain,” the general said. “We’ve been waiting.”

“My dear,” he gestured to the woman with a softness I hadn’t seen in him, “this is the officer I told you about.”

She smiled—faint, precise—and said something in Polish that I didn’t know but understood. The boy let go of her coat long enough to wave. His fingers were not blue anymore.

The general’s voice did not change registers; his eyes did. “Captain, I owe you an explanation.” He gestured me to sit. “My wife is part of a NATO humanitarian team. Two weeks ago, her vehicle got separated in the storm. Comms down. Fuel low. We assumed the worst.” He paused long enough for that to land. “I now know you stopped. You gave my son food. You moved on.”

“Sir, I—” I started, but my throat closed.

He held up one hand, as if to stop me from stepping on grace. “You didn’t know who she was. That is what matters. You weren’t performing. You were remembering.”

The boy walked up and placed a small object in my gloved palm—a wrinkled chocolate-wrapper, smoothed by small fingers. “He keep it,” the woman said in careful English, “from that day. Soldier gave him hope.”

My lungs did the thing lungs do before tears and I have never forgiven them for that. I swallowed, hard, and tucked the foil into the inner pocket of my blouse like it deserved armor.

“You reminded me,” the general said quietly, leaning on his desk as if the room had moved, “that regulations without compassion congeal into cruelty. We lead better when our hearts don’t freeze before our hands.”

“I… understand, sir,” I managed.

“You didn’t do it to be understood,” he said. “You did it because you still know what right actually feels like. Don’t lose that and don’t let this place sand it off you.”

He stood. “Walk with me.”

In the corridor, the radiators hissed. Outside, beyond the glass, the motorpool looked like a diagram of everything practical—fuel cans, chains, tarps laced like corsets. He nodded at them. “Those men out there,” he said, “will forget half of what we order them to do. They will remember every decent thing they see us do when we think no one is watching.”

He stopped where the hallway widened into a window and a view. “Thank you, Captain Hayes. Not for breaking the rules. For remembering why the rules exist.”

“Roger, sir,” I said, because sometimes humor is the only way a Marine can accept grace.

He almost smiled. “Dismissed.”

Part IV — Meet My Wife

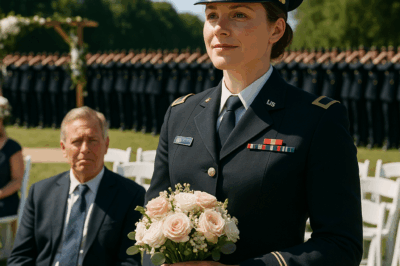

Two weeks later, the hangar was scrubbed clean and dressed in flags. We were ordered into dress blues. The air smelled like wet wool and the last ten minutes of a storm.

Rows of folding chairs faced a stage built from pallets and hope. I took a seat near the back with the other captains, because the best view in a room isn’t where the power sits; it’s where the power moves.

The general stepped onto the makeshift stage. Beside him, in a gray coat with her hair pinned back and her scarf folded into humility, stood his wife. Their son sat with a NATO pin too big for his small chest, his feet not yet touching the floor.

“Two weeks ago,” the general said, voice threaded through a microphone that decided to be kind, “one of our officers made a decision. It broke protocol. It preserved something more important.”

A few heads turned in my direction. Marines are good at pretending not to look where they are looking.

“Captain Morgan Hayes,” he said, and my name felt larger than my coat. “Front and center.”

I stood because the order fit me and marched because my legs remembered how. He didn’t make me stand at attention; he didn’t make me kneel to receive a medal that would tarnish under fluorescent lights. He turned to his wife and said, loud enough for the whole building to hear:

“Captain, meet my wife.”

The room laughed—not the polite kind that hides cruelty, but the human kind that lets tension step outside and smoke. She shook my hand again like we were adding a chapter to a book that had been mis-shelved. “You remind me why we come,” she said. “Why uniforms matter.”

The general held up a small case. “Not valor,” he said, almost apologizing to the tradition that likes its medals attached to smoke and visible wounds. “Humanitarian service.” He pinned the ribbon himself—above my heart, where now two small pieces of metal shared a geography: regulation and decency.

He leaned in as the room clapped; his voice was just between us. “I thought I had taught this place everything I learned. Turns out I forgot the first lesson.” He tapped the ribbon with one finger. “People.”

I stood a half-inch taller because sometimes humility is easier to carry when someone else says it out loud.

After the ceremony, Jenkins shoved a paper cup of coffee into my hand and stage-whispered, “Saint Hayes. That’s what they’re calling you.”

“I hope not,” I said. “Saints get less sleep and more assignments.”

“Your speech was good,” he said.

“I didn’t give one,” I said.

“Exactly.”

The general’s wife found me near a spool of cargo netting. “In my country,” she said, “we have a saying: A good hand leaves warmth behind. You did.” She took my hand again, shook it once, and let go. I pressed the chocolate-wrapper through the fabric of my pocket and felt the crinkle like a promise.

Part V — Letters That Don’t Freeze

We ramped operations. Snow turned to slush turned back to powder. Fuel schedules multiplied like rabbits. The rest of the winter learned how to be long. I reread my father’s half-written field letter—the one I started months before and never mailed—and finished it:

Dad, you told me once that mercy has no place in command. Out here I learned command without mercy turns into something we don’t want to be. I didn’t break protocol to be a hero. I broke it to be human. I think you tried to teach me honor your whole life. I think I finally learned it.

I mailed it with gloves on. A week later, the mail truck returned carrying a reply scrawled in the handwriting I’ve been learning to read my whole life:

Morgan, when you were a kid I told you heart gets you hurt. Truth is, heart got me through thirty years. I just didn’t like admitting it. You did right. — Dad.

I read it three times, folded it into my journal beside the chocolate-wrapper and the ribbon citation. Metal, foil, paper—the three weights I ended up measuring the winter with.

The general stopped me by the fuel depot the next morning. “You heard from home,” he said.

“Yes, sir.” I tapped my breast pocket. “Paper is heavier than ice, sometimes.”

He nodded. “Keep that,” he said. “The pride of a parent can outrank a thousand salutes.”

We walked toward the line of trucks. The young Marines checked chains with numb fingers and an efficiency born of practice. The general watched and said, to himself more than to me, “It’s stewardship.”

“Sir?”

“What command is,” he said. “Not control. Stewardship. You reminded me.”

I was not promoted after that. I wasn’t demoted either. My punishment was more work and my reward was the same. It felt right.

On my last free morning before rotation home, I walked along the road where we had stopped. The fence line still leaned toward the field like a tired old man. Snow had rewritten the ground but left the air the same, thin and cold and honest.

“Stay to the treeline,” I said to no one, and laughed at myself because sometimes memory is ridiculous in the quiet.

I knelt. Pressed my glove into the snow until my palm stung and then wrote our call sign in the powder with one finger, small as a prayer. The wind erased it before I stood.

On the flight home, the cabin smelled like canvas and fuel and men relieved enough to brag again. Jenkins tapped a beat to a country song leaking out of his headphones and thumbed a text to someone back home who has taught him to hope. I slept and woke and slept and dreamed of a woman shaking my hand as if I had handed it back to her.

They gave me a small ceremony in Washington—a ribbon in quiet metal, a few words that meant more because they were careful with volume. The general’s wife found me afterward and pressed a crayon drawing into my hand: a stick figure Marine with a bun under her cap giving a rectangle to a smaller stick figure under falling dots labeled “SNOW.” Underneath, blocky letters: Thank you hero. I kneel for kids. I don’t kneel for many others. “You’re the hero,” I told him. “You survived.”

In my apartment that night, I set the ribbon in a drawer beside my father’s letter and the chocolate-wrapper. Then I wrote this in my journal:

Honor isn’t what they pin to your blouse or call you in a room. It’s what you keep warm when no one is watching.

I closed the book. I let the silence expand until it felt like company.

Sometimes redemption doesn’t enter in brass and ceremony. Sometimes it arrives shivering in a scarf, nods once, and disappears again. Sometimes it comes in the mail with your surname on it and a sentence you’ve waited your whole life to hear. Sometimes it sounds like a general saying, “Meet my wife,” and remembering who he was supposed to be.

If you ever doubt what difference one small act can make, remember this: someone you will never meet might be alive because of it. Someone you do know might become who they intended to be because they watched you do it.

That is enough to make a career. That is enough to make a winter worth its teeth. That is enough to make a life.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I Was Shattered When I Saw My Father Slap My Mom And Call Her ‘Useless’ In Court…

I Was Shattered When I Saw My Father Slap My Mom And Call Her ‘Useless’ In Court… Part One…

CH2. My Parents Ignored My Wedding — Then Demanded a “Family Meeting” After Seeing My Vice Admiral Fiancé

My Parents Ignored My Wedding — Then Demanded a “Family Meeting” After Seeing My Vice Admiral Fiancé Part I —…

CH2. My Dad Mocked My Appearance at the Wedding – Then Spat Out His Wine When the Groomsman Saluted…

At my son’s wedding, my father decided to humiliate me in front of everyone. With a smirk on his face,…

CH2. My Dad Mocked My Military Wedding—Until 150 Soldiers Saluted Me

My Dad Mocked My Military Wedding—Until 150 Soldiers Saluted Me Part I — The Text, the Laugh, the Uniform…

CH2. My Father Introduced Me as “His Little Clerk” — Then His SEAL Friend Realized I Led UNIT 77.

My Father Introduced Me as “His Little Clerk” — Then His SEAL Friend Realized I Led UNIT 77. Part I…

CH2. My Wealthy Father Thought My Army Pay Could Barely Cover Rent — Until I Walked In with…

My Wealthy Father Thought My Army Pay Could Barely Cover Rent — Until I Walked In with… Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load