I came home after years away – and found Dad in a hospital, on life support. Mom and my siblings? Partying in Bali… I froze the family bank account.an hour later, chaos hit like a storm…

Part I — The Beeping Room

The sound is what stays—the ventilator’s metronome, unhurried and merciless. It counted time the way men in my family always did: by what was still moving. Dad’s chest barely rose. Tape striped his skin. The white of the room made the dark of his hands look unreal, like someone had swapped them in a bad painting. I stood at the foot of the bed and understood three things at once: he was alive, he was alone, and no one had been here for days.

The nurse confirmed it without looking up from the monitor. Visitors in the log? None. Two weeks. The word developed edges. Two. Weeks.

When I stepped into the corridor to breathe air that didn’t smell like bleach and compressed air, my phone lit up with the world I had left behind. A photo—mom tagged on a terrace in Seminyak, arm threaded through my sister’s, my brother leaning in, brown shoulders and teeth and a champagne bottle tilted as if gravity owed them deference. Captions that burbled. Sun emojis. The word blessed, which did not belong to this hospital.

Something in me broke like a wave at the pier and hardened like the concrete it broke against.

I’d left home three years earlier with Dad’s “Take your time” tucked in my pocket. London had been loud and good and clarifying. Calls home shrank from daily to weekly to holidays to a silence I pretended we all needed. While I learned the price of weather and food and the tube, Mom learned how to be photographed without Dad in the frame. My brother learned how to sign for deliveries of watches. My sister learned what angle made generosity look like a brand.

Two weeks. No visitors.

I called the nurse station from the hall. Bills? Unpaid. Primary contact? My mother. The nurse’s jaw tightened in the way people do when their opinion costs them nothing and buys them the right to look away. “There’s a number on file,” she said. “It goes to voicemail.”

I called the number I never called first. Mom answered on the third ring with party in the background and a voice that tried to be hushed and failed. “We’re… darling, we’re at dinner. What—”

“He’s on life support,” I said. “Two weeks. Alone.”

“Oh,” she said, the sound you make at a painting you don’t understand. “Sweetheart, we were told it was… stable.”

“You posted champagne an hour ago.”

Silence took a chair. The music on her end kept going.

“Flight tomorrow,” she said at last, like generosity. “We’ll organize.”

I hung up because I had no words that didn’t taste like ash.

Lawyers keep their phones on if you are the person their best client trusts. Mr. Adler had mine labeled with an old nickname Dad liked—Kiddo—and picked up before the second ring.

“Hospital,” I said. “He’s intubated.”

“I’m sorry,” he said, and it had gravity. Then: “Power of attorney?”

“Dad gave it to me,” I said. “Three years ago. In your office. You witnessed.”

“It’s still in force,” he said. “You want me to send the hospital the letter?”

“And the bank,” I said. “Freeze everything in Dad’s name and every family account tied to the company. Effective now.”

“That will set a grenade off,” he said, not arguing.

“The house is burning,” I said. “Better we pull the pins ourselves.”

He didn’t say brave. He said, “Done.”

By the time I slid the chair to Dad’s bed and threaded my fingers through his, my phone was a storm panel. Six missed from Mom. Four from my brother. Two from my sister. A text from an unknown Indonesian number: “Your card declined. Please advise.”

I set the phone face down. The ventilator counted. I counted with it.

Part II — The House They Forgot to Own

The company had started in Dad’s study with a laptop and a wall map and lines drawn with string. Logistics—pallets and routes and the math of hours. He ran it with the discipline of a man who had learned that time is either your ally or your executioner. Mom handled the part he didn’t believe necessary and therefore never understood—galas, interviews, the smile whose corners never moved toward her eyes. My brother took pictures that looked like business. My sister took the word charity out for drinks.

When I left for London, Dad said, “We’ll hold the fort.” He meant, I will. Turns out the fort was only as strong as the person who cared to walk the walls at night. Six months into my course, an email forwarded by one of Dad’s oldest dispatchers slid into my inbox. Resignation. The reasons were polite and wrong: “restructuring,” “new direction,” “best wishes.” Then another. Then the rumor everyone serves with coffee: Mom’s in charge now.

I flew home once, for Dad’s birthday. The office smelled like her. His portrait was gone; a blown-up magazine cover of Mom at a gala hung in its place. My brother sat in Dad’s chair and spun it too fast. My sister “handled the accounts,” which looked like a new phone and three mentions in a lifestyle piece about giving back. The bookkeeper I grew up with handed me a paper napkin with numbers on it and a look that said he had tried. “Money’s wrong,” he mouthed behind his coffee. “Wrong how?” He squeezed his thumb and forefinger together. “Like someone’s siphoning a very slow leak.”

By the time I got back to Heathrow, Dad had collapsed.

In the hospital lounge, I opened my laptop and a folder I had built on plane rides and in insomnia: fake charity transfers that routed to a foundation Mom had registered in Bali; “consulting fees” for influencers who never consulted; shell companies with directors whose addresses were beach villas. All paid under Dad’s name. All signed by a hand I recognized and had learned not to trust.

Adler came in wearing his usual navy and a face men put on for morgues and boardrooms. He handed me a coffee I didn’t want and papers I did. “You have control,” he said. “You’ll get blowback.”

The blowback took form. Mom’s voice shook when I finally answered. “You ruined everything. Do you understand? Everything your father built.”

“No,” I said. “I saved it from you.”

My brother texted a photo of himself half-crying, half-anger—in a way only men who are certain money will fix them know how to do. “Unfreeze. I can’t pay the staff. This is on you.”

“You fired half the staff,” I replied. “The ones who said no to your cards.”

My sister’s message was a masterclass in reframing: “You don’t understand what it means to keep an image. We were protecting the brand.”

“Dad is the brand,” I wrote. “He’s breathing through a machine.”

An hour later, Adler’s audit team took over the conference room with a printer that made a sound like judgment. The first statement came back with the kind of red you don’t explain away in interviews. They followed the river of money to the sea it had chosen. The sea had a pool bar.

Mom flew back with sunglasses enormous enough to hide a small animal. Reporters were waiting; the questions had knives. She swept through with that smile I knew—pageant-perfect—until the camera angle betrayed panic. My brother tried damage control on a morning show in a blazer that fit and a truth that didn’t. My sister live-streamed crying in a car between apologies and accusations, collecting comments the way we used to collect shells at low tide, shiny and worthless.

At the hospital, the nurse on nights switched the TV off above Dad’s bed. “Noise is bad for them,” she said. “Even if they can’t hear.”

“I think he can,” I said.

She nodded, not because it was medically accurate, but because it was kind.

Adler brought a smaller set of papers at ten, unceremonious as weather. “The power of attorney lets you bar visitors,” he said. “You want me to handle the fallout?”

“They had two weeks,” I said. “They chose a beach.”

He took the words and left because good lawyers know when ethics is personal.

When their shadows appeared through the frosted glass, their perfume arrived first. It smelled like oranges and expensive. The door didn’t open. I sat. The ventilator counted.

Part III — The Day He Opened His Eyes

Dad woke a week later the way old machines start—slowly, suspicious of miracles. His chest rattled. The nurse, who had eyes like someone who has lost things and learned not to let that define her, eased the tube and gave him a breath with a bag, and then hands did what hands do when they are ready to be back to their job. They worked.

“Hey,” I said, and it was both a word and a prayer.

He looked at me like a man on shore looks at the person who dragged him out of a rip current he pretended he wanted. “Where,” he mouthed, and his brow creased around a story that had yet to be told.

“Hospital,” I said, squeezing his fingers. “You’re safe.”

His eyes asked another question. It wasn’t about tubes.

“Gone,” I said. It wasn’t complete, and it wasn’t cruel. It was accurate.

He closed his eyes and exhaled like a man who believed the word. When he reopened them, he pointed, small and precise, to the laptop on the chair. It took him three tries to sign what needed signing. Adler countersigned with a pen that glided, and our quiet coup became a matter of record instead of rumor.

The cleanup took months and a part of my hairline. The audit mapped a longer, older rot than even I, trained in suspicion, had imagined. They had leveraged the company to photograph generosity; they had mortgaged the house to import status symbols; they had turned the word charity into a convertible. We turned their speed into sand.

The foundation became an actual charity staffed by people who knew how to move food from donors to those who needed it. The company paid vendors in the order Dad would have chosen: the ones with small shops and big hearts first; the ones who had carried us when our margins were thin and our luck thinner. The press found a new story and then another because that’s what press does. The friends who were only friends as long as the champagne flowed resolved themselves into categories that needed no labels. I answered only what mattered.

They asked to see him. They tried every door—legal, medical, social. I shut the ones I could and left open the one Dad had taught me mattered: if a person walks toward reconciliation with clean hands and no cameras, you hear them. If they come with knives hidden in napkins, you feed the dog and go to bed.

My sister called from a cheap apartment that photographed like punishment. “I’m sorry,” she said so loudly it sounded like a dare. She wanted absolution that spent like cash. Dad was asleep. I was tired. I said nothing. The line filled with the kind of busy that has no dial tone.

Mom filed for bankruptcy in a dress the color of trying. My brother fled to a city that likes hiding, forfeiting the company car on the way to the gate. In a photo that made the rounds, he wore sunglasses that reflected a man taking a picture of a scandal and an old man reading a newspaper who had seen worse.

Dad learned to sit up, then to swing legs over the bed, then to stand between parallel bars with a therapist built like compassion. He hated needing help until he learned that accepting it was also a form of leadership. The first day they let him shuffle to the window, he saw the skyline he had learned every exit of, and the tender anger on his face softened. “I should have done it sooner,” he whispered.

“What,” I said.

“Trusted you,” he said. Then, because he was who he was, “What’s our on-time delivery this quarter?”

“Ninety-six percent,” I said.

He smiled in the shape of a man who had built something that still stood and then asked what we were going to do about the four percent. We made a plan.

Part IV — After the Storm

The company survived. The family did not. There is a grief you cannot plant; it does not grow and therefore it does not die. It simply sits, a rock in a field you mow around. Mom became a person who lined up at a different counter. My brother sent two emails from Dubai and a photo of a skyline that looked like a screensaver. My sister posted a redemption arc in soft pastels and aspirational quotes, and for a minute, the internet believed her. Comments are not currency; neither are they forgiveness. Sometimes they are just noise.

Dad asked about them every visit. I told him the truth every time. He nodded in a rhythm that said he had known how this story ended when he gave me the folder three years ago. When he came home, he sat at the kitchen table he had refinished three times and taught himself how to use a cane without making it a personality. He came into the office on Tuesdays and Thursdays for two hours and changed the color of a highlighter on a scheduling board because it offended him. I let him. He earned his quirks the hard way.

There is a kind of revenge that looks like fire; I didn’t need it. Mine looked like signatures and audits and the refusal to answer calls whose only purpose was to recycle an old script. The day Adler texted that the last of the shell companies had been unwound, I turned my phone off and walked a route Dad and I used to run when he was teaching me the city: along the water, past the place where the cranes look like animals, under the bridge that kept missing its paint job. Weather happens. You build anyway.

A year later, on an afternoon the color of steel and hope, I drove Dad to the office in a car that started every time and parked in a lot that used to be gravel and was now properly paved. The crews were eating late lunch on tailgates. A dispatcher waved with a mouth full of sandwich. My project manager came out with a sheaf of change orders organized with tabs the way he knew I liked. We walked past a wall of photos—foundations poured, shipments loaded, that one winter when the river froze hard enough to call the news.

On the far end of the hallway, there was an empty space, a rectangle of paint lighter than the rest where Mom had hung a magazine cover and I had hung nothing. Dad stopped. “Give it to the dispatcher,” he said.

“The space?”

“The recognition,” he said. “The people who don’t sit at tables.”

We called everyone in and did it standing up. No speeches, just names and hands and a pizza order big enough to require math.

In the quiet after, I walked back to my office. The blinds were open. The city kept moving. My phone buzzed one last time: a message from a number that had once belonged in my favorites.

“Do you ever think about what we were?” Mom wrote. “We were happy.”

We were photographed, I did not type. We were convincing. We were a story. I deleted the draft and answered nothing. Silence, I had learned, can be the kindest boundary. It keeps both of you from lying.

That evening, at Dad’s house—the house now in a trust with rules that would outlive all of us—we ate takeout with paper napkins because sometimes ceremony is just weight. Dad looked tired in the way men do when they’ve done honest work learning to be alive again. He put his cane by the door the way a man puts his keys where he’ll find them tomorrow. He asked if I’d locked the accounts down to require two signatures. I had. He smiled and turned the TV to a baseball game he no longer pretended to enjoy. It wasn’t about the game. It was about noise that did not require a response.

On my way out, I stopped by the hospital wing that had held us in its bright mouth and took the long corridor one last time. The nurse on nights was there, charting. She raised her pen without breaking rhythm. “He’s good,” she said. “I saw him shuffle past yesterday. He complains in complete sentences. That’s a good sign.”

“It always was,” I said.

I stepped outside and the cold grabbed my lungs the way it does in a city that never apologizes for being itself. I missed London a little, its softness and book stalls and riverside drunks who sing badly. I loved this place more—its cranes and the smell of shipping containers and the way our trucks made tracks as honest as signatures.

I hadn’t come home to burn anything down. I had come home to sit by a bed. Then I’d done what had to be done. When chaos hit like a storm, I didn’t flinch. I stood by the only person in this story who had always stood by me. I froze the accounts because money was the weapon they trusted most. I signed the papers because my hand was the quietest one in the room. I made the call because the only thing that saves a house is someone who knows where the beams go and refuses to pretend the cracks aren’t there.

They learned who took his place. It wasn’t the people who pose well. It wasn’t the people who found sunlight and called it blessing. It was the person sitting in the chair by the bed, counting with the machine and waiting for the chest to rise on its own. It was me.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I adopted my nephew after my sister died. Christmas came. My mother-in-law said, “Only real…

I adopted my nephew after my sister died. Christmas came. My mother-in-law said, “Only real grandchildren at dinner. Don’t bring…

CH2. Her boss secretly erased her raise — But she built the system that exposed every lie

Her boss secretly erased her raise — But she built the system that exposed every lie Part 1 The…

CH2. My brother jeered my inheritance, saying he’d get the house and dad’s business; until the lawyer…

My brother jeered my inheritance, saying he’d get the house and dad’s business; until the lawyer… Part I —…

CH2. The Irony: ‘Leave!’ They Said, Unaware of My Ownership. The Moment I Revealed the Truth.

The Irony: ‘Leave!’ They Said, Unaware of My Ownership. The Moment I Revealed the Truth. Part 1 “I don’t…

CH2. You’re Being Selfish! Said My Son And His Wife Threw Wine At Me, So I Texted My Lawyer!

You’re Being Selfish! Said My Son And His Wife Threw Wine At Me, So I Texted My Lawyer! Part…

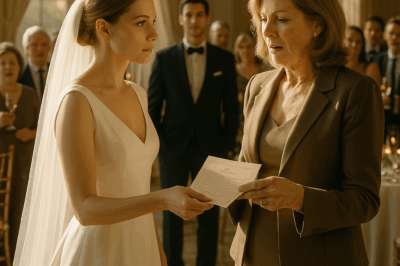

CH2. At My Wedding, Mom Smirked: “It’s Just a Car.” So I Handed Her the Legal Envelope…

At My Wedding, Mom Smirked: “It’s Just a Car.” So I Handed Her the Legal Envelope… Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load