I Bought Mom Flowers for Mother’s Day. She Used Them to Sweep the Floor — “Your Sister Gives Real Gifts.”

Part I — The Last Petal

I stood in the doorway holding a simple bouquet of roadside wildflowers tied with a blue ribbon I’d ironed flat from an old school project. It wasn’t much, but it was what I had. I’d saved for the wrapping paper, skipped lunch for two days, and spent the morning walking the shoulder of County 12 hunting yellow cores and purple flares, the kind that look cheap in a florist and priceless in a ditch under sun.

“Hi, Mom,” I said, stepping into the living room where she and my sister Camille sat like two queens who’d survived a war they had never fought. The talk show blared. Their feet were on the coffee table I’d refinished with a sander and stubbornness. The house smelled like fabric softener and peppermint oil—clean, practiced, unwelcoming.

Camille glanced over the top of her phone and snorted. “What’s that supposed to be? A compost project?”

“They’re for you,” I said, jaw doing that thing it does when the body tries to hold the soul still. “Happy Mother’s Day.”

My mother turned her head like she was turning a page she’d already read. Her mouth curled. “You brought weeds?”

“They’re wildflowers,” I said quickly, heat crawling up my neck. “I picked them myself. The yellow ones are—”

She took the bouquet mid-sentence, not gently, and walked to the kitchen like she was carrying something that could stain. For one hopeful second, I pictured a mason jar, cold water, a quiet nod. Instead, she opened the back door, dragged the bouquet across the muddy welcome mat, and used the stems like a filthy mop, grinding petals into grit.

“These are weeds,” she said over her shoulder. “Your sister brought a spa voucher and a silver necklace. You brought trash. This is what nobodies give.”

Camille laughed from the couch. “Maybe next year you can give her rocks. At least they won’t wilt.”

I stood there with a ribbon imprint on my palm and the knowledge that some pains don’t ask permission before they move in.

“Pick that mess up,” my mother added. “I won’t have your shame lying around the house.”

I knelt. My fingers shook as I gathered wet stems and crushed color back into the paper. Camille filmed me on her phone and sang “Smile for the camera, weed girl,” in the voice reserved for humiliations you plan to replay later.

That was not the first time they made me small. It was the first time something inside me shifted from bending to rooting.

My little brother, Mason—seven, messy-haired, half-toothless—found me later in my room staring at the ribbon. He held out a peanut-butter sandwich with crusts cut off like I used to do for him.

“I didn’t bring flowers,” he whispered. “But I got you this.”

I took it. I did not cry then. Not from kindness. Not from cruelty. Not from the knowledge that someday this boy would learn what the word burden feels like when it comes from a parent’s mouth.

He learned sooner than I wanted him to.

Part II — The Night the Papers Hit the Trash

Three years bled by the way water chews the underside of a dock—slow, patient, inevitable.

Camille got a job at a fashion boutique with floor-length mirrors that replaced the need for character. Dad pulled strings to get her in. I pulled double shifts at the diner down on Route 7 to pay off community college classes in the mornings. I learned the posture of a waitress who can balance three plates and a smile while praying for a shift without hands that wander when they tip.

When I came home after midnight smelling like grease and coffee grounds, Mom would wrinkle her nose and say, “Could you use the back door? The smell makes the couch stink.”

Camille brought boys home with cars louder than their jokes. One of them asked if I was the maid. She didn’t correct him. She didn’t even look up from her phone. She laughed.

I had a plan: survive college, get a better job, move into a studio above the hardware store where the landlord forgets rent when you shovel his sidewalk. But plans yield to emergencies the way paper yields to rain.

Mason started coughing. It didn’t stop.

His skin went the color of office paper that’s been left in the sun too long. He ate like food owed him nothing. The clinic doctor listened to his chest and sent us to a specialist who spoke softly, wrote quickly, and said words that turned the room cold: congenital heart defect—intervention—monitor—cost.

I took him to every appointment. I held every clipboard. I memorized every dosage, every schedule, every micro-expression the nurses made when they checked the chart and tried not to sigh.

I saved tips in a jar with MASON scrawled in block letters. I learned which charities covered which forms of care and which administrators never lost paperwork you hand-delivered with muffins.

At home, Mom said, “It’s just a phase.” Dad said, “He’s weak. Probably takes after your side.” Camille came to the hospital once, took a selfie with Mason while he slept, captioned it Blessed. She stayed seven minutes.

Then one night, I came home smelling like hash browns and fear and found Dad at the kitchen trash can. He was tossing—methodically, clinically—the folder with the insurance forms, the approval letter, the surgery estimate, the list of payment plans.

“What are you doing?” I grabbed for the papers, hands stupid with panic.

He didn’t even look annoyed. “We’re not paying for this garbage.”

“He could die,” I said. I wasn’t screaming yet. Screaming never moved the mountain in our house. It only made avalanches.

“He’s already a burden,” Dad said, tone cool as a glass of water held just out of reach. “Maybe it’s better we cut our losses now.”

He struck me when I hunched to catch a page sliding toward the linoleum. Open palm. No warning. I hit the edge of the dining table, went sideways, felt the floor bite. The room tilted. The world shrank to pain and the sound of breath that barely counts.

He stood over me like he was waiting to see if I’d break neatly. “You deserve that,” he said. “Always trying to play hero. For what? Trash raising trash.”

Mom appeared in the doorway holding a mug. Steam curled around her face and made it look like fog. She took in the scene with a glance that was not concerned enough to be called cold.

“If you want a medal for suffering,” she said, “join the military. This is just parenting.”

Something inside me stopped asking to be loved. Something else started counting. Not days. Not dollars. Not debts. The minutes until I could leave without looking back.

I moved Mason into my room that night. I pushed my dresser against the door. It was a cheap gesture against a deeper danger, but cheap gestures sometimes hold walls up long enough to plan.

I took online business classes after school. I learned design software at the public library on a computer that whined when you asked it for too much. I picked up an extra shift at the garden center that smells like dirt and decisions. The manager, Ruth, wore floral gloves and swore like she invented the words. She took to me like a person who recognizes the way grief turns into work.

“You’ve got hands that want to heal,” she said, watching me untangle roots from a crumbling pot. “That’s rare. Don’t let anyone make you ashamed of it.”

The only thing shame builds quickly is silence. I put mine down and started building other things.

Part III — Weeds & Wildflowers

I named the little business Weeds & Wildflowers on a dare to myself: love the things they stomped.

It began with art printed on demand—mugs, shirts, dish towels—quiet designs that said the things I could not yet: Resilient is not a synonym for disposable. No is a complete sentence. Bloom where they told you to sweep.

Orders trickled in, then quickened when Ruth let me stack tea towels next to the bee balm. The first time a hotel placed an order for custom napkins, I cried behind the shipping boxes and blamed the dust.

When Ruth offered me her side greenhouse for a dollar and a handshake, I said yes before she finished the sentence. I learned propagation the way some people memorize songs. I hybridized flowers by lantern light with hands that had made a different kind of promise to a different kind of care.

The first strain I bred held color the way secrets hold shape—deep, stubborn. I named it Amara (grace I never received). The second, Lena (lionhearted). They were bright and hearty enough to survive neglect, like me.

I moved product through farmer’s markets, then bouquets at the boutique hotel near the interstate, then table arrangements for the citywide gala—hosted, ironically and perfectly, by my sister’s employer.

Camille didn’t know. Not until the paper ran a profile on the young floral phenom transforming the city’s design scene. My name was spelled correctly on the front page. The picture showed Amaras spilling like fire across a table that belonged to people who didn’t know what ditch they came from.

The neighbor texted me later: Your mom’s fuming. Says you must have cheated.

I sent Mom a bouquet. $300 worth of blooms that took three months to coax from stubborn earth. The card read: From one nobody to another. May your floors stay clean.

She didn’t sweep with those. The neighbor said she put them in a glass box.

Ah, the alchemy of shame: what you once used to scrub a mat becomes what you glue under a bell jar when other eyes are watching.

I didn’t gloat. Revenge is easy when you are hungry. I fed something else: a foster home’s budget, with half my profits and a handshake. I named my third strain Jorah (repentance), though nobody who needed it recognized their reflection.

Boxes stacked in our living room, warding the space off like little cardboard towers. I used our address as a return center. Dad complained. I shrugged and bit my tongue on the words he would never understand: This is the sound a future makes when it’s being built where you thought you had destroyed the foundation.

Mason’s cough quieted. The charity covered more of his care. He sat in the greenhouse corner on a stool Ruth called “the throne” and drew bugs with dignity. He learned the names of flowers faster than he learned the spelling words school insisted on. He learned that his big sister’s hands could keep heartbeats steady.

They didn’t ask. They didn’t notice. They posted pictures of Camille’s bouquets from chain florists and captioned them #blessed.

Some weeds don’t choke. Some hold the soil in place long enough for a garden to happen.

Part IV — The Bloom & The Boil

The city gala was a turning point. Amara glowed under chandeliers. Women who never tie their own shoes asked for my card. Men with cufflinks talked about partnerships and I smiled and thought about payroll.

Camille floated through the room like she had invented glass. She did not recognize my work. Why would she? Nobody taught her to see how things begin, only how they look when they end up under lighting she didn’t hang.

Two days later, the local news asked to film in my greenhouse. Ruth wore clean overalls and cried when the anchor said my name. “I knew your hands wanted to heal,” she told the camera, which is also exactly what she told me, but it sounded prettier on air.

Mom did not call. Dad did not text. Instead, a letter arrived in a white envelope, handwriting I know better than my own.

Dinner Sunday. Camille says your flowers would make a nice centerpiece.

I wrote back: Bring a dustpan.

The night before the Sunday I refused to come, I heard the front door slam. Voices rose. Dad’s was not angry. It was scared. “Medical bills? Again?”

Camille had relevance when she cried. She’d always known how to use tears like a tool. She stormed into my room and threw a pamphlet on my bed: spa package. Not a voucher—an invoice.

“Can you cover this?” she asked, face arranged in helplessness. “Mom wants to go with me for her birthday.”

“She can come sweep the greenhouse,” I said. “I pay in compost.”

She called me names that make younger versions of me flinch. The older version asked if she needed directions to the door.

They didn’t go to the spa. They went to church and prayed for my soul.

Their prayers weren’t wasted. Souls need attention. But miracles take work, and I had that.

The morning Mason’s cardiologist said words that sounded like music—“stable… improved… remarkable response”—I walked out of the clinic into sunlight that had the courtesy to be warm.

Mom texted that afternoon: Don’t forget Camille’s brunch tomorrow. Wear something nice.

I sent back a photo of Amaras going to a wedding with the caption: Busy.

She read it. She liked it. She did not understand she was liking the thing she once called trash.

Sometimes you can’t teach people to read you. You can only learn to read yourself well enough to ignore their illiteracy.

Part V — The Sweep

The day everything boiled over was not orchestrated. It was ordinary in the way rooms are ordinary the minute before a picture falls off the wall.

I came home from a delivery to find Dad pacing with a manila envelope in his hand and Mom on the phone, voice pitched to perform distress for an audience who couldn’t see her hands not shaking.

“What is it now?” I asked, setting my keys in the dish I’d hot-glued metal leaves onto.

“Property tax,” Dad said, as if taxes are personal attacks. “I can’t keep paying for this house alone.”

“You could sell the SUV,” I said. “Or the illusion.”

Camille swept in with a bag from the boutique and set it on the table, strategic logo aimed toward anyone who might be taking notes. She saw the envelope and the way the air had changed.

“Don’t start, Anna,” she said, like I had invented either the mail or gravity. “Some of us have reputations to maintain.”

“By draining a bank account you didn’t build?” I asked.

Mom slid her glasses down her nose and looked at me the way a woman looks at a stain you can’t lift. “Your sister gives real gifts,” she said, as if the words tasted sweet. “Spa days. Silver. The kind of things that show you care.”

I looked at Mason on the couch, asleep after school with a book on his chest and the kitten Ruth found lodged beside his ribs like a second heartbeat. I looked at my hands and saw dirt under my nails and a future in my palm.

“You used wildflowers to sweep your floor,” I said. “And now the city sweeps my flowers down red carpets while you call them weeds.”

Mom’s smile faltered, reflex reaching for a joke. “You never did know how to take criticism, Anna.”

“I learned,” I said. “That’s why I don’t live in it.”

Dad thumped the envelope. “I need you to cover this month. And the next. Camille’s bonus got delayed.”

“I covered eighteen Christmases and two emergencies I didn’t cause,” I said. “I covered Mason’s prescriptions and a roof leak and a tire you never replaced. I covered childhood with an adult salary for people who used the word real as though cash makes love truer. I’m done.”

Camille laughed, high and sharp. “You ‘run’ a greenhouse. Don’t act like you’re Jeff Bezos.”

“I run a payroll,” I said. “It pays me in peace.”

Dad took a step closer. “Don’t disrespect me in my house.”

“You threw out the paperwork that kept your grandson alive,” I said. “You lost the right to be respected in mine.”

Mom moved toward the kitchen, away from the conversation. Her voice floated back, a last-ditch correctness. “It’s lunchtime. I won’t argue hungry.”

“Good,” I said. “I’m not arguing.”

I opened my bag, pulled out a white envelope, and set it on the coffee table. It was not property tax money. It was a deed.

Camille’s face lost its angles. “What’s that?”

“The deed,” I said. “To this house.”

Dad’s mouth opened, then forgot what it was for.

“I bought it,” I said, calm as dirt. “On the courthouse steps last week when the county posted the overdue notice you ignored. I paid cash. It’s in my name. There’s no mortgage. There’s no lease. There’s a new arrangement.”

Mom braced a hand on the counter like the room had moved. “You can’t just—”

“I can,” I said. “And I did. You can stay. On one condition.”

Camille snorted. “You don’t get to make conditions.”

I looked at Mason, waking now, blinking toward the sound of voices. I looked at the wall where a framed picture of Camille’s high school graduation had hung for years. I looked at the spot on the floor where flower petals had stuck under somebody’s shoe.

“You don’t sweep my gifts,” I said, “when I am the one buying your home.”

Silence landed. Not empty. Heavy. It sounded like a doorframe learning a new hinge.

Dad spoke first, voice small, a sound I had never heard. “What… what’s the condition?”

“You treat me like I matter,” I said. “You treat Mason like he matters. You treat the rooms you live in like they are not disposable just because you didn’t pay for the paint. You stop using real to mean expensive and start using it to mean earned. You don’t insult the things I grow and then call it love when you lock them under glass.”

Mom’s mouth trembled, which made her look like the woman who taught me to tie my shoes and make scrambled eggs, not the one who made me pick petals from a mat. “Anna—”

“And you apologize,” I said softly. “For that day. For the flowers. For the last three years. For throwing away papers that saved your grandson’s life because you didn’t want to look poor. For every time you told me I was a nobody.”

Dad sank into the chair like a man who has found out gravity is permanent. Camille looked at her hands. The phone finally slid to the table face down.

Mason swung his feet off the couch and padded over to me in socks that didn’t match. He slid his small hand into mine and looked up at our parents with a seriousness that made me want to cry for every version of him that would never need to.

“Say you’re sorry,” he said.

It wasn’t a demand. It was a blueprint.

Mom nodded. It wasn’t pretty. But it was raw. Which is how truth looks when you stop lighting it like a talk show.

“I’m sorry,” she said to the carpet. Then to me. Then again, louder, to the room. “I’m sorry.”

Dad’s apology was clumsy and real. He added “I love you” like the words were new and he was trying them on for size. Camille’s came last and angry and resentful and still something. I took them and I didn’t put them on, but I hung them near the door for later.

“Here are the rules,” I said. “Rent is your presence. Payment is your respect. You don’t have to love me. But you will not sweep me. Not again.”

Camille looked at the deed again, then at me, then at the bouquet in the glass box in the corner. “They were pretty,” she said, small.

“They still are,” I said. “That’s kind of the point.”

Part VI — The Bouquet Under Glass

Spring folded into a summer that did not demand anyone pay for it with humiliation.

Dad fixed the fence posts with Mason, asking him how to hold the drill and letting him show. Mom started taking afternoon walks with me around the block. She picked up leaves and learned the names I’ve held like spells. Bee balm. Coreopsis. Rudbeckia. She said Amara once and it came out as a question and I said grace and she looked like someone had told her the translation for herself.

Camille came home from the boutique with tales of customers who don’t look cashiers in the eye. She started looking them in the eye. She cleans up after dinner without my telling her where the sponge lives. She asks about the greenhouse, the hotel orders, the wedding with the bride who cried because the centerpieces smelled like the ditch where her dad used to fish.

One morning, Mom appeared in the backyard where I was staking dahlias and said, “Teach me?”

I handed her shears. “You’ll bleed once if you don’t listen,” I said. “That’s how most lessons show themselves.”

She nodded, and when her thumb nicked a thorn and she hissed and I didn’t say I told you so and she didn’t blame the plant, something old unclenched between us.

I don’t rewrite history to make it pretty. Some things are too deep to edit. The part where Dad hit me still exists. The part where Mom used flowers as a mop still exists. The part where they adored Camille’s borrowed spa voucher and used my blue ribbon to tie up a trash bag still exists. The jar where I keep the words nobody wants to admit they said still exists.

So does the day Mason ran across the yard and jumped into Dad’s arms and both of them didn’t pretend it was anything but joy.

I didn’t win because I made them small. I won because I made myself the size I always was.

Wildflowers feed entire fields when you stop calling them weeds. They hold soil on hills that would otherwise slide.

On the mantle, next to the glass box with petals pressed under thick edges, sits a new frame. The photo shows a table dressed in Amaras and Lenas, Mom’s hand on my shoulder, Dad’s hand on Mason’s head, Camille mid-laugh, a little blade of humility catching the light.

Sometimes Mom dusts the glass box. She doesn’t sweep with it anymore. Sometimes she dusts the frame too. She does it gently.

On Mother’s Day, I bring her flowers. Real flowers. Easy to say now because she knows what that means. We put them in water.

“Happy Mother’s Day,” I say, and the words are not a test anymore.

She looks at me. “Happy Mother’s Day,” she says back, like she means to the woman who taught me how to apologize. Then she puts a hand on my cheek where once it split and says, “Thank you for not throwing me away when I used your love to clean a floor.”

“I didn’t do it for you,” I tell her, because honesty is a better detergent than guilt. “I did it for me. And for him.”

Mason slides a peanut-butter sandwich across the table, crusts cut off. He is taller. He hasn’t learned to pretend yet. I hope he never does.

We eat. We listen to the yard be loud with things that don’t know they were ever unwanted. We let the ribbon fall where it belongs: around stems in a jar of cold water, tied by hands that never needed permission to be gentle.

That night I sit on the porch and watch the streetlights make halos out of dust, and I think about a girl on her knees picking petals off a mat, and I want to go back and put my hand on her head and say what I wish someone had said then:

You are not a weed. You are the thing that keeps the hill from sliding. You are the thing that blooms anyway. You are the bouquet under glass and the field outside and the person who gets to decide which one you want to be today.

The next morning, I walk out to the greenhouse and smell warm dirt and see Ruth’s old stool and the first Jorah of the season opening itself like truth.

I cut one carefully and bring it inside. I put it on the kitchen table in a jar of cold water. And before the others wake up, before the day remembers it is busy, I run my thumb along the rim, and I thank the version of me who learned how to grow things where other people sweep.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

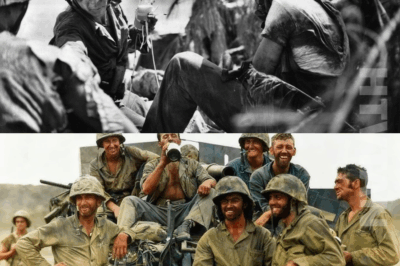

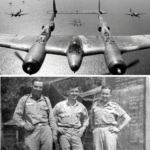

CH2. When Marines Needed a Hero, You’ll Never Guess Who Showed Up!

When Marines Needed a Hero, You’ll Never Guess Who Showed Up! Sunday, September 27, 1942. The jungle on Guadalcanal breathed….

CH2. This WW2 Story is so INSANE You’ll Think It’s Fiction!

Quentin Walsh was Coast Guard—but in WWII, he was handed Navy orders and sent behind enemy lines to capture a…

CH2. Making Bayonets Great Again — The Savage Legend of Lewis Millett

Making Bayonets Great Again — The Savage Legend of Lewis Millett The first time Captain Lewis Millett saw the Chinese…

CH2. 3 Americans Who Turned Back a 5,000 Man Banzai Charge!

3 Americans Who Turned Back a 5,000 Man Banzai Charge! Friday, July 7th, 1944. The night over Saipan was thick…

CH2. The Most Insane One-Man Stand You’ve Never Heard Of! Dwight “The Detroit Destroyer” Johnson

The Most Insane One-Man Stand You’ve Never Heard Of! Dwight “The Detroit Destroyer” Johnson Monday, January 15th, 1968. In the…

CH2. The Wildest Medal of Honor Story You’ve Never Heard — Commando Kelly!

The Wildest Medal of Honor Story You’ve Never Heard — Commando Kelly! On the mountainside above Altavilla, the night burned….

End of content

No more pages to load