I Asked My Wife, ‘Do You Love Him?’ She Said Who I Said ‘Patrick,’ and She Froze

Part I

I asked Rebecca quietly, “Do you love him?”

She blinked, confused. “Who?” she asked.

I said, “Patrick.”

And the moment the name left my lips, everything changed. The silence that followed was deafening—louder than any admission could have been. Even the hum of the fridge, the soft ticking of the clock, and the distant rumble of the storm outside seemed to vanish, leaving only her uneven breath, caught between guilt and fear.

When she didn’t answer, I knew. I didn’t yell or move; I didn’t pound the table or go for the door. I just watched her eyes, those blue-gray searchlights, dart nervously toward the hallway, toward the dark rectangle of the window, toward anywhere but me—searching for a way out of a room that had suddenly become too small for the both of us.

Finally, she muttered—almost too quietly—“Why would you ask that?”

“Because you’ve already told me,” I said. Not with words, but through the countless hints you left: lingering glances, delayed replies, the faint smile that appears whenever his name comes up.

The living room held itself very still. Rain threaded down the panes in long, liquid wires. The lamplight made a halo of gold hair around her face; she looked like a girl I once knew, the one who used to tie her hair with a red ribbon and laugh when I pretended to steal it. But that was another house, another season, another version of us. I saw the wedding photo on the shelf—my hand on her shoulder, her hand covering mine—and realized the picture had always been a still image of motion: two people walking toward a future they hadn’t yet constructed or priced.

Her hands shook as she lifted her wineglass. “You’re imagining things, Daniel. Patrick’s your friend.”

“He was my friend.”

That single word landed harder than the accusation. I saw it bruise her, a small flinch at the corner of her mouth. Weeks ago, the first cracks had appeared like hairlines in a porcelain cup you tell yourself will hold one more pour. Laughter that lasted two beats too long at a joke I hadn’t heard. Texts angled away from me as if the screen were cold and needed the warmth of her body alone. A new perfume, citrus with something bitter beneath it. I convinced myself it was paranoia; jealousy gnawing at the trust we’d built, chewing through walls I swore were load-bearing.

Truth doesn’t scream. It whispers patiently until you lean in to listen and feel its breath cooling your ear.

The night I realized everything, Patrick had joined us for dinner. Rebecca wore a red dress I hadn’t seen in years, the one with the little bow stitched into the small of her back. She brushed past me to greet him, her smile too warm, too familiar. He complimented her cooking and she blushed. When I did, she barely looked up, said, “You always say that,” as if my praise were a script she’d learned by heart and grown bored of.

That night I began noticing the patterns. The phone buzzing late, the sudden evening walks (“I need to stretch my legs, it helps me think”), the private murmur of laughter in the hallway when she thought I was asleep. Every small, unguarded moment pulling at the seams, and the seams surrendering to fingers I couldn’t see.

And now, as the storm outside battered the windows, I asked softly, “How long?”

Her face drained of color. “I don’t know what you mean,” she said.

“Rebecca, don’t make me drag it out of you.”

She stared at me, tears threatening to spill before whispering, “It just happened. I didn’t mean for it.”

I let out a bitter laugh. “They all say that. Like love is a loose stair you miss in the dark.”

She looked at me then—not with guilt, not with anger, but with pity so gentle it burned. “You’ve been so distant, Daniel. Always working, always tired. I was lonely.”

The word sliced through me not because of its meaning but because of its accuracy. I’d taken on extra shifts; I’d stayed late to impress a man whose first name was “Mr.” and whose last name meant dividends. I told myself I was building us a fortress of comforts: new gutters, better tires, a future that didn’t squeak when the wind rose. And in doing so, I traded time for money and left my post at the door of our marriage, unguarded.

“I didn’t want to hurt you,” she said.

“But you did,” I answered, my voice low and steady. “Every day you lied. Every time you smiled at me knowing your heart was elsewhere.”

She cried then, shoulders trembling. Some ancient reflex in me moved to comfort her—the part trained by years of shared mornings and cups of tea, the part that knew the exact slope of her collarbone under my hand. I gripped the edge of the table to stop myself.

“When did it start?” I asked.

She hesitated. “After the company party.”

Six months of deception. Six months of her slipping away while I remained blind, wiping fog from a mirror that wouldn’t clear. I saw it all at once: the gradual withdrawal, the sudden interest in the gym, the humming while texting, the new habit of standing near windows as if the night had a voice only she could hear.

“Do you love him?” I asked again, softer.

Her lip quivered. “I don’t know… but I did.”

The pause held the confession—the time inside the sentence where she measured the cost of truth and found it too heavy to lift. She stood, hugging herself. “It’s over now. We ended it.”

I shook my head. “No, Rebecca. You ended us.”

Thunder rolled, a bowling ball through a heavenly alley. She turned her back and dabbed at her face with the sleeve of her sweater, a gesture I had always found tender, domestic, unguarded. Now it only looked like retreat.

“What will you do?” she asked.

I didn’t know. Rage and grief collided inside me until they were indistinguishable. Part of me wanted to confront Patrick, to put my hands on his shirt and press him against the wall until the plaster learned his name. Part of me wanted to vanish into a motel with a buzzing neon sign and a key the shape of an arrow pointing anywhere but here. The part of me that won grabbed my keys.

“I need air.”

She reached for me. “Daniel, please don’t do anything rash.”

I hesitated, almost taking her hand. Then I pulled back. “Too late.”

The drive was a blur of rain-slick streets and brake lights smeared into red wounds by the wiper blades. I don’t remember making the turn onto Patrick’s block, only the sudden knowledge that I had arrived, that the building’s brick facade was wet enough to shine beneath the streetlamp. His windows were rectangles of yellow. Shadows moved behind the curtains. Then the lights went out.

I could have gone up. I could have waited and demanded answers any decent man would never give me honestly. But the truth already sat beside me in the passenger seat, buckled in and breathing quietly. What I despised most wasn’t Patrick—it was the version of myself that trusted without turning the object over in my hands to feel its weight; the version that mistook routine for loyalty and silence for peace.

I drove until the storm cleared, the rain thinning to a tired mist. My hands unwound from the wheel when I reached the old pier where Rebecca and I had once planned a trip we never took. The water mirrored a faint moon, the surface only occasionally freckled by dying droplets. I remembered her laughter, the way her fingers interlaced with mine, a braided promise of always. We were so young then—not in age, but in the foolish certainty that vows outrun loneliness simply by being said.

At home, the house was silent. She slept on the couch under a blanket, curled like a comma, a pause between what she’d done and what would happen next. Innocent and peaceful, almost as if nothing had changed—until I remembered everything had.

I took off my wedding ring and set it on the coffee table. The soft clink sounded like a knell for something sacred. In the morning, I packed a bag. She woke as I left.

“Where are you going?” she asked, voice gravelled with sleep and crying.

“Somewhere you can’t follow.”

“Please. We can fix this.”

I paused at the door. “You can’t fix what died while you were pretending to keep it alive.”

I stepped into air that smelled of wet leaves and earth and a distant bakery that always opened too early for reason. For the first time in months, I felt a flicker of peace. Not forgiveness. Not yet. The peace that comes after devastation, when nothing is left to lose and nothing left to hide.

Driving away, I realized I had already found closure the moment she froze.

Part II

I checked into a roadside motel with a name that sounded like a promise and smelled like old bleach. The clerk handed me a key card and a smile engineered by corporate policy. Inside, the room hummed with a single tone all motels know—air conditioner, mini-fridge, and the thin electricity of escape.

I sat on the edge of the bed, shoes still on, and tried to hold the moment without folding it into rage or sentimentality. I wanted to believe I was the kind of man who could map a way forward like a city planner, each block designated for a healthy function: sleep here, grieve there, exercise in that park, eat at this diner that doesn’t ask who you were before you arrived. But maps lie by omission. They show you where the roads are, not the ground that swallows under your feet.

My phone buzzed. Rebecca: Are you safe?

Yes.

A minute later: Please come home. Let’s talk when you’re ready.

I heard enough.

I set the phone face down. The old habit wanted to flip it back, to watch the little ellipsis appear and disappear—the visual of someone building a sentence against your silence. I let it be. I showered too hot and stood under it until the water turned lukewarm and honesty replaced pretense: I was exhausted. I slept with the television on mute, a blue pulse flickering against the curtains.

In the morning, I bought coffee from a window and walked along the bay. The storm had scoured the sky; it lay clean and careless above me. I found a bench and sat, feeling foolishly like a man in a movie who had fled a city to learn the language of his own thoughts. A jogger nodded as he passed. Somewhere, a dog barked twice—a sound like punctuation.

I thought of Patrick. He had sat at my table, poured my wine, asked after my mother. When my car wouldn’t start last winter, he came with jumper cables and a joke about batteries that made me roll my eyes. I replayed every memory I had of him, looking for the forensic hints I had missed: The way his compliments to Rebecca had matured from generic to tailored, the subtle proxies of intimacy—“Remember when you said…”—spooled so casually I had never caught the thread.

My phone buzzed again. A message from an unknown number, the kind of text that will never be a pizza delivery announcement: Daniel, it’s Patrick. We should talk.

I stared at the message until it blurred. Then I put the phone back in my pocket because I knew that to answer now would be to step onto a stage that had already been built for me, with blocking and lighting and a closing line that would leave both of us in the dark. If he wanted absolution, he’d approach a priest. If he wanted a fight, there were bars. If he wanted to tell me the truth, he should have considered me a deserving audience months ago.

Instead, I called my sister, Nora. When she picked up, I said her name and nothing else. She heard everything inside it.

“Where are you?” she asked.

“A motel near the bay.”

“Do you want company?”

“No. But I want your voice.”

She gave it freely. Nora is one of those people whose sentences carry weather—the warmth of spring afternoons and the clarity of early winter mornings. I told her what I had asked Rebecca and what Rebecca hadn’t answered; I told her about the storm and the drive and the way the ring had sounded against the coffee table like a small, polite death.

“I’m sorry,” she said. The simplest phrase. The least ambitious. The most necessary. “Come stay here. I’ll make the guest room look like it’s always belonged to you.”

I nodded to the air. “I will.”

“And Daniel?”

“Yeah?”

“Don’t write the ending before you’ve lived the middle.”

“I’m not writing anything,” I said. “I’m erasing.”

“Erasing is a way of writing,” she said softly.

On my way to Nora’s, I stopped at the storage space where my father kept his old fishing gear. The unit smelled like rope, old oil, and the sweet decay of cardboard. On a shelf sat the tackle box he swore would last longer than the sun and nearly did. I turned it over in my hands, feeling the grooves his fingers had worn into the plastic. Grief is strange: I was in a crisis of fidelity and all I could think about was a man who had once loved me so loudly it echoed for years after he was gone. I took the box and a soft, threadbare sweatshirt that smelled like boat mornings, and I left the rest of his artifacts to their quiet rot.

At Nora’s, the guest room did, in fact, look like it had been waiting for me—fresh sheets, a glass of water with a lemon slice floating like a small moon, a book on the nightstand she knew I loved. She didn’t ask questions until I started answering the ones she hadn’t posed.

“Do you think,” I asked, “that love can run out? Like a battery you forgot to charge?”

“I think,” she said, sitting with her feet tucked under her, “that some kinds of love run ahead and expect you to keep pace. If you don’t, they feel abandoned. Other kinds wait. You should decide which kind yours was. Not so you can blame either of you, but so you can name the terrain you walked.”

“Rebecca said she was lonely.”

“Were you?”

I opened my mouth to say no. Closed it. “Sometimes,” I admitted. “But I thought loneliness was the fee you paid to build a life that wouldn’t break in a routine gust of wind. I thought everyone swallowed it, then went to sleep.”

Nora reached over and squeezed my wrist. “If you swallow it long enough, it learns the way out.”

I slept at her place that night—heavy, dreamless sleep that feels like surrender. In the morning, I woke into the ordinary sounds of someone else’s kitchen performed by someone who loves you: the click of the kettle, the radio hosting two strangers arguing amiably about the weather. I was surprised by how intact I felt, the way a building can look on the outside after the interior has been gutted—facade surviving, space for new rooms yawning behind it.

Rebecca called. I let it ring out. She texted: I’m sorry. I know that’s not enough but it’s true.

Later: I ended it. He knows never to contact me again.

Later still: Can we meet? Somewhere public if you want. I’ll answer what I can.

I stared at the messages and thought about our first date—a diner with sticky menus and a waitress who called us “honey,” as if we’d already earned such familiarity. Rebecca had drawn a constellation of syrup on the table with the tip of her knife and told me the story of the scar on her shin from when she tried to jump a creek at eight. I remember thinking: I could love this person who narrates herself like a novel with pages dog-eared in the soft parts.

I typed: Tomorrow, Black Finch Café, 2 p.m.

She replied: I’ll be there.

That night, I answered Patrick’s text with three words: No more contact. If he sent anything after that, I never saw it. I blocked the number because self-preservation isn’t cruelty; it’s the maintenance of a border someone has already trespassed.

At the café the next day, Rebecca sat at a table near the window, her hands wrapped around a mug as if heat could reassemble her. She looked tired in a way mascara can’t hide and good sleep can’t cure. I stood in the doorway long enough for her to feel my presence and then to decide whether to meet my eyes. She did.

“Thank you for coming,” she said when I reached the table.

“Don’t thank me.”

She nodded. “Then I won’t. I’ll just talk.”

“You’ll answer,” I corrected.

She exhaled. “I’ll answer.”

“Why him?” I asked.

She blinked as if the question had arrived in a language she understood but hated to speak. “He listened,” she said simply. “Not to my words, not exactly, but to the parts of me I kept erasing because I thought they weren’t useful. He noticed the way I touch my wrist when I’m anxious, how I go quiet when I’m deciding to lie rather than disappoint. You…you notice other things. The thermostat. The wiper blades. The best routes around construction.”

“We played positions on the same team,” I said. “He pretended to be the stadium.”

“That’s cruel,” she said, a flare of heat in her voice, not because she thought I was wrong but because the metaphor made her glow in a way that hurt us both. “I’m not defending him. I’m trying to tell the truth.”

“Tell the truth, then. Did you love him?”

Her mouth worked around the answer before she offered it. “I loved what I was around him,” she said. “I loved feeling central. The sun in someone’s day. With you, I was…home. And I forgot that home is a place you build each morning. I started believing it just exists, or it doesn’t.”

“You told me you were lonely.”

“I was. I’m not saying this to make you responsible for what I did. I did it. I walked toward it, and then I ran. But loneliness is a joint venture. We both invested. We kept receipts.”

I thought of the nights I’d fallen asleep on the couch with a spreadsheet open on my laptop, the way ambition can sound like love if you use a gentle voice. I thought of Rebecca asking if we could take a weekend to drive somewhere without reservations and me saying, “Sure, sometime,” as if sometime were a magic word that conjured infinite forgiveness.

“What do you want from me now?” I asked.

She looked at me as if I’d asked how to change the weather. “I want to give you whatever you need to go on,” she said. “If that’s silence, I’ll learn it. If it’s answers, I’ll speak until my throat dries up. If it’s divorce, I’ll sign.”

“Do you want a divorce?”

“I want you to stop hurting,” she said, which wasn’t an answer, and in that absence I found my own.

“We’re going to end this,” I told her. “Not with shouting, not with a scene that burns more than it cauterizes. We’ll end it like people who remember why they tried in the first place.”

She closed her eyes and nodded once. “Okay.”

We chose a lawyer recommended by Nora’s friend—a woman whose office shelves held not trophies but plants that looked well-watered. She spoke to us in practical sentences and paused long enough for us to place our sorrow between them. Papers were filed. Waiting periods were explained. There were forms to list assets and forms to list debts and a line on a page for irreconcilable differences which felt, in its smallness, like a dare to make a longer list elsewhere.

At home, I visited our house at times when I knew Rebecca wouldn’t be there. I packed in phases so I could understand what my life weighed. Books first, heavy with other people’s words. Then clothes, the dishonest fabric of memory saying, You wore this the night you… Then the tools I had amassed like talismans against helplessness: a torque wrench, a set of hex keys, a paint roller that still smelled faintly of the blue we chose for the room that would never become what we thought.

I left the dining table with its four chairs, the couch with the stain we hidden under a throw pillow, the lamp whose shade sat slightly crooked no matter how often I straightened it. Objects are innocent until you ask them to be relics.

Rebecca sent one more message the night before the final signing: I know I don’t get to say this, but I hope you are happy—someday, not now. And I hope it’s the kind of happiness that doesn’t need to be declared to exist.

I read it twice and didn’t answer. Some things you send into the world not as a plea but as an offering; I was learning how to receive without responding.

Part III

The courthouse smelled like paper and old optimism. We signed. Our names flowed over lines as if they had always been trained to land exactly there. The clerk stamped; the stamp made a sound too cheerful for what it signified. We walked out through doors that might have been church doors if this were a different kind of loss.

Outside, the day was unreasonably beautiful—blue sky performing its simplest trick. Rebecca and I stood on the steps, side by side, not touching. People in suits and skirts and sneakers moved past us carrying their own endings and beginnings in folders and on faces. She turned to me.

“Thank you for being kind,” she said. “I didn’t earn it, but I needed it.”

“You gave me years,” I said. “I won’t pretend they were nothing just because they ended.”

We walked down the steps and parted at the sidewalk, each turning without looking back because looking back would have been a performance we didn’t need to stage. I walked without destination until my body decided the park would hold me, and when I reached it, I sat on a bench with peeling paint and watched a child fly a kite that refused to rise. He tried again and again, and each time the kite nosedived, he laughed like failure had opened a new pocket of air.

I went back to Nora’s and cooked dinner. I diced onions too finely because the knife felt good in my hand and precision felt like a kind of control. Nora talked about a book club she didn’t like but kept attending because she liked the way the room smelled of cinnamon and old carpet. We ate and ignored the empty chair.

The days after were ordinary, which is to say miraculous. I woke, made coffee, ran, worked, walked, slept, woke again. Ordinary does not mean painless; it means the pain learned a schedule and respected it. I returned my father’s tackle box to the storage unit and took out a wooden frame he’d built for me when I moved into my first apartment. I sanded it down and painted it the color of wet slate and hung it on a wall that had waited politely for art.

One evening, at the grocery store, I saw Patrick in the freezer aisle, his face pinched above a stack of pizzas that promised more than they could deliver. He saw me too. We froze—two animals on either side of a road measuring distance and danger. He opened his mouth. I shook my head, not out of anger but completion. He closed his mouth and nodded, once. We both moved on, and the hum of the coolers filled the space where our old friendship had died.

I started therapy at Nora’s insistence and my own reluctant recognition. The therapist’s office was a second-floor room over a florist. The place smelled faintly of water and green. On our first day, she asked me why I had come, and I said, “Because my marriage ended,” and she said, “And why else?” and I realized I had more than one reason and each had its own weather.

We talked about boundaries and the kinds of work you can’t outsource. We talked about the difference between leaving and escaping, about how one strategy closes a story and the other drags it behind you until it shreds and you are left with fragments you keep trying to reassemble in kitchens at 3 a.m. We talked about forgiveness as a gift I could wrap with paper I liked, even if I never delivered it.

Sometimes I missed Rebecca like you miss an old injury: the ache when it rains, the memory of the break, the bitter gratitude that the body learned to stitch itself back together. Sometimes I didn’t think of her at all for hours and then felt guilty for the relief.

Months passed. I learned the names of neighbors I had never known, not because of loneliness, but in defiance of it. I fixed a screen door that had stuck since spring and felt a flicker of pride far larger than the job deserved. I found the old pier again on a clear night and watched the water keep its promises to the moon.

When the papers arrived in the mail, final and unromantic, I opened them at the kitchen counter and read each page as if the words would say something different if I held the paper at a different angle. They didn’t. I set them down and took a walk because movement was the only thing my body trusted fully.

On the third block, I saw a woman struggling with a stack of boxes outside a storefront with a sign that read Second Chance Books. She balanced the top box with her chin and swore gently when it slid. I caught it before it fell. She laughed—a sound that felt like a window coming unstuck—and said, “Thanks. You just saved the poetry section.”

“Can’t have that,” I said.

We carried boxes together, and when the last one was shelved, she offered me a glass of water in a paper cup stamped with blue leaves. Her name was Maya. She had a way of tilting her head when she listened that made you feel edited—shearing off the needless words, keeping the sentence true. We talked about books. We talked about the pier. We did not talk about marriage or betrayal or the way the world can correct your course without asking.

I walked home with a used copy of a novel I had lost years ago and found that the simple presence of a book in my hand had shifted the air in the apartment—like a minor chord resolving to major when you weren’t sure it would.

That night I dreamed of the version of myself who had sat at the table and asked his wife if she loved another man. In the dream, I looked at him and didn’t pity him; I didn’t despise him either. I put a hand on his shoulder and said, “You’ll be okay,” and woke believing myself.

Part IV

Spring arrived without hurry, the way a shy guest steps into a room and pretends she was always there. On a Saturday morning soft enough to wash the week clean, I drove to the bay and stood on the pier. Kids in orange vests patrolled the railings with nets. A couple took photos that would look like happiness no matter what they felt; sometimes that’s a mercy.

My phone buzzed. A number I knew and would always know. Rebecca: I’m moving next month. I thought you should know, in case there’s mail.

I’ll update my address. Thanks.

Are you okay?

I looked at the water, the way it lapped the pilings with an old dog’s patience. I am. I hope you are too.

A long pause. Then: I’m learning to be alone without calling it punishment.

Good, I wrote, and meant it.

I slipped the phone back into my pocket and let the morning carry me. A breeze lifted and fell like a sleeping chest. If grief is weather, healing is climate: not a day’s worth of sun, but a pattern you can plan your life around.

On the way home, I stopped by Second Chance Books. Maya had a plant on the counter that looked like a tiny palm tree. “Meet Gloria,” she said. “She and I are on speaking terms now that I remembered to water her.”

“Rough patch?”

“She’s very forgiving,” Maya said, and her eyes flicked up to mine, amused and something else—acknowledging that the word had range.

We talked for ten minutes that felt like five. I left with a book of essays about ordinary things: toast, pencil sharpeners, the socks you find behind a dryer three months too late. On the last page, the author had written, This is where you decide what the small things mean. Choose carefully. I closed the book and thought of coffee mugs and door hinges and the constellation of tiny habits that make a life brighter than the light that strikes it.

That evening, I cooked for Nora and her boyfriend, Omar, a man with a laugh that makes other people laugh by accident. We ate on her balcony. Below us, the city performed its thousand rituals: dogs walking people, bikes rowing through traffic, a man singing on a corner because he couldn’t not. There was nothing glamorous about any of it, and yet it shone.

After they left, I washed the dishes by hand even though the machine waited with its practical mouth open. I dried each plate and placed it in the cabinet with the ordinary care of a person who knows where everything lives. I thought of the ring I had set on the coffee table months ago. I wondered if Rebecca still kept it somewhere. I hoped she would do with it whatever turned it back into metal and not memory.

In bed, the window open, I listened to night olfactories—a neighbor’s cumin and garlic, the faint salt off the bay, the forgotten sweetness of cut lawn drifting even from blocks away. I didn’t feel triumphant. I didn’t feel hollow. I felt like a man in a room he chose, on a bed he made, beneath a ceiling that didn’t threaten to fall.

In the morning, I wrote a letter I didn’t plan to mail—to the man I was, to the marriage I lost, to the friend I no longer had. It began with the sentence: I forgive you for believing work could build warmth the way bodies do. It continued with smaller mercies. I folded it and placed it in my father’s tackle box because the box had proven it could keep safe what a person treasures, even when the person doesn’t know the value yet.

Days became weeks, and the weeks built a scaffold I could climb without fearing the sway. One Sunday, Maya closed the shop early and asked if I wanted to walk. We wandered without aim, our conversation like a tide that rose and fell around our feet. We passed the courthouse where I had unmade a promise and the park where a kite once refused to rise. We reached the pier and leaned against the rail.

“Do you come here often?” she asked.

“I used to come here to remember,” I said. “Now I come to practice forgetting. Not names or faces—just the way pain wants to be the only story I tell.”

“And how’s the practice going?”

“Better when the weather’s like this.”

She smiled. “Then you’re learning to rig your own climate.”

We stood together in the softened light. A boat nosed past, its wake scribbling temporary lines that the water erased. I thought of the night I said Patrick’s name and watched my wife freeze, that sudden, brutal shift from ignorance to knowledge. If I played it again, frame by frame, I could still locate the exact second when a life swiveled on its hinge. But I didn’t feel the old vertigo. I felt steadier than that. I felt…placed.

I won’t pretend there was one last sign from the universe—a bird sweeping low at the perfect moment, the sky flaring with cinematic intention. The world simply kept being itself. That was enough.

We turned back toward the city. Somewhere a bell rang for a service I wasn’t invited to but could have attended if I’d wanted. A child asked a question his mother couldn’t answer, and they laughed about the not-knowing. I put my hands in my pockets, and my fingers found a folded slip of paper I’d forgotten I’d tucked there, torn from the author’s essay about small things. On it, in a hand that was finally mine again, I had written: Choose the meanings that make you generous.

That night, alone in my apartment, I stood at the window and watched the lights decide themselves on. I poured a glass of water and set it on the nightstand. A small thing, a necessary thing. I lay down and closed my eyes.

I dreamed, not of confrontation or loss, but of a house with many rooms and windows accurate to the wind. In the dream, I walked from room to room turning on lamps, not because I feared the dark, but because I wanted to see what I had. When I reached the last room, the window was open. The curtain lifted once and settled. I touched the sill, felt the smooth grain under my hand, and knew—without needing to hear it said—that the answer to the question I had asked months ago had ceased to matter. The only question worth asking now was the one I could finally answer.

What will you do?

I will live.

And I did.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

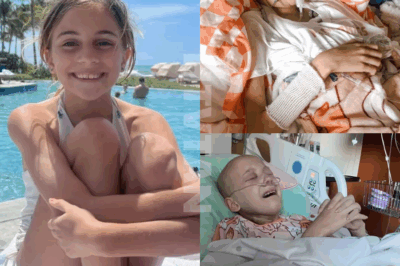

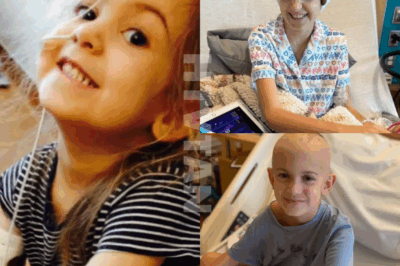

CH2. Ada’s Bravery: Overcoming Childhood Leukaemia

Ada’s world changed overnight when, at just 5 years old, she was diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. What followed were…

CH2. Sasha’s Last Breath: Held in Love Until the Very End

Sasha — The Light That Wouldn’t Go Out This morning, the world fell silent.Our brave Sasha took her final breath —…

CH2. Cancer-Free and Heaven-Bound — Rylee’s Beautiful Journey

Rylee was only six, but she lived with more courage and love than most do in a lifetime.When cancer came,…

CH2. Zuza Beine: A Life of Courage and Light

At just three years old, Zuza was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia — a battle that would last more than…

CH2. Nellie’s Song — The Baby Who Smiled Through the Storm

She was only three months old when her parents began to worry — her laughter fading, her tiny body growing…

CH2. Rodney ‘RJ’ Enoch III — A Little Angel, A Lasting Light

Rodney S. Enoch, III, lovingly known as RJ, was born on December 14, 2023, bringing instant joy to everyone around…

End of content

No more pages to load