I adopted my nephew after my sister died. Christmas came. My mother-in-law said, “Only real grandchildren at dinner. Don’t bring that boy.” I stayed quiet. I just texted, “Understood.” On Christmas morning, she opened her gift from us—56 missed calls from her

Part 1

She called on Christmas Eve with the voice she saved for waiters and grandmothers—polite, lacquered, weaponized. “We’re keeping dinner small this year,” my mother-in-law said. “Just family. You understand.” The word family lingered like perfume, or poison.

I was at the table helping my nephew tape orange paper to a lopsided snowman he’d drawn—“for the nose,” he said, serious as a surgeon. He looks like my sister when he concentrates: brow pinched, lips pursed, eyes ringed with that precise, earnest light children wear right before they do something they’re proud of. My sister’s smile lives in his face. Her laugh sometimes leaks out of him when he forgets to be careful.

Then my mother-in-law said it. “Only real grandchildren at dinner. Don’t bring that boy.”

The words were calm. Practiced. The kind a person tries out on their tongue in a mirror to see if their reflection blinks.

I didn’t argue. I let her finish her performance and hang up. Then I texted one word: Understood.

The tree blinked its sugar-colored lights at the wall. In the living room, the television murmured a cartoon he wasn’t watching. My nephew asked, “Are we going to Grandma’s tomorrow?”

“Grandma’s busy,” I said, steady. “We’ll have Christmas here.” He nodded like it was a plan he could help build. He went back to taping the nose on his snowman. “It’s okay,” he added, unprompted, as if he had heard something I tried not to say.

When my sister died, the coroner took her body and the hospital took her charts and the world took a step away and watched me decide. I signed the papers. I took her son home. I promised the sleeping shape of my sister’s absence I would keep him safe—safe from pity, from bureaucracies that smell like bleach and stale coffee, from people who count love in bloodlines.

My wife’s mother never understood that vow. She smiled at him the way people smile at guest dogs—wide, performative, far away from the eyes. In private, she told my wife, “He’s not yours. Don’t let him grow up thinking he is.” She said it as if she were offering a recipe. For years I ignored it. I told myself not to fight battles beneath me. Then I learned that if you hold your head too high, you’ll miss the kick to the ribs.

That night, my wife set out two plates and two wine glasses, touched the stem of each as if making a wish. “Mom’s making roast duck,” she said. “And chestnut stuffing. She sounded…excited.”

“Old-fashioned,” I said, testing her word. It tasted like rust. “That’s what you said, right? She’s old-fashioned.”

“She didn’t mean—” My wife’s voice trailed into the song she turned up too loud. She poured wine into both glasses and handed me one like it could anesthetize me into complicity.

Later, I stood in the kitchen doorway and watched her laugh into the phone. “He said it’s fine,” she told her mother, eyes on her reflection in the window. “He understands.” She listened, nodded, said, “We’ll open presents there in the morning.” She did not look at me. The window speech-bubbled her breath into the dark. She sounded like someone who had learned that comfort is easier when you let somebody else pay the price.

I tucked my nephew in. He whispered into the pillow, “Good night, Mommy,” the way he does when he is tired enough to forget how time works. I sat in the hallway until his breathing evened. I shut the door. On the kitchen table, the wine had gone flat. The tree blinked at me like it had a question it was tired of asking.

I made a list: Things That Matter. Things That Don’t.

By two a.m., one name had slid from one column to the other and stayed there. I drafted a message. Deleted it. Wrote it again. And again. When I had boiled it to the right size, I scheduled it for 9:00 a.m. I wrapped my mother-in-law’s gift—something small, metallic, painfully symbolic. I tied it with red ribbon because I wanted to be precise.

In the morning, my wife dressed in a red sweater and a careful smile. She kissed my forehead. “We’ll only be a couple of hours,” she said.

“I know,” I replied. I picked up my nephew. We went outside. We built a snowman. He gave it a crooked grin and called it Kevin for reasons he couldn’t explain. The air had that quiet that happens when snow listens for its own landing.

By noon my phone lit up: a photo from my wife—her mother at the tree, cheeks pink, mouth open in a performance of surprise. Then another photo, her smile mid-collapse. In her lap: a box that did not hold jewelry or perfume. It held a phone. Her phone. I had borrowed it when she came for tea last week, just long enough to copy her contacts and add a new one. I had set it to autodial three digits and then mine, over and over, a loop with a tail.

When she looked down, the screen bloomed red: 56 missed calls, all from the same number, all timestamped since 9:00 a.m. She looked for the contact name. She found the one I created and placed under my number: The Boy’s Dad.

She called me, voice a little cracked at the edges. “What is this supposed to mean?”

“It means,” I said, “for every second you told yourself that boy wasn’t family, I remembered.”

“Are you threatening me?”

“No,” I said. “I’m reminding you.”

She hung up. My phone shook in my hand. Seconds later, my wife called, angry, brittle, frantic. I let it ring. Some truths don’t need an argument; they need an echo chamber.

That night my nephew slept hard, his mouth softened into a smile that made him look younger than his years. I watched his chest rise and fall, counted until my heartbeat matched, then went downstairs and turned my phone face down. Snow kept falling. It covered the street and the walkway and the sharp pieces you can’t see until they cut you. I believed in quiet long enough to let it do its work.

Part 2

In the morning, I made hot chocolate. My nephew ate a pancake shaped like a star and held up a Lego person he’d named after me. He said, “This one doesn’t fall down.” I laughed because the alternative was to cry.

My wife texted: You went too far.

I stepped outside, let the cold grab my lungs, and tried to turn the sentence into something that didn’t accuse me of protecting a child. The sky refused.

At noon, there came a knock. Not sharp. Nervous. My wife stood on the step, hair powdered in snow, eyes wild with the adrenaline of wanting to be right. She stepped inside without asking. Our nephew shouted her name and ran to hug her waist. Her body softened around him on instinct. Some things happen before you can decide whether you’re capable of them.

She pulled away first. “You humiliated my mother.”

“She humiliated my son,” I said.

“He isn’t—” She stopped. The word yours hovered, uninvited.

“Say it,” I said. “Say the quiet part.”

She stared at the wall, the way people do when they hope a new reality will be projected there for them to step into. “She didn’t mean it,” my wife whispered. “She’s old-fashioned.”

“Old-fashioned is vinyl records and a manual coffee grinder,” I said. “Old-fashioned is not cruelty with better manners.”

“She’s eighty. She says things.”

“And she has you to translate them into something you can live with.”

My nephew reappeared with the Lego man. “Auntie, he can stand on one leg,” he said, delighted.

She tried to smile. She managed a shape that could eventually become one with practice.

“We’re going to the park,” I said. “It’s a sled day.” I put the Lego man in my pocket like a talisman. I bundled him into layers until he remembered he had toes. My wife followed us halfway down the sidewalk and stopped as if the snow had turned to glass she was afraid to crack.

At the park, the hills made children reckless and parents older. I dragged him to the top and we flew down. He laughed the way my sister used to laugh when the world forgot to scare her. At the bottom, he shouted, “Again!” We went again. His cheeks went the color of apples. On the fourth run, he fell off, rolled, popped back up, and threw his mittened hands in the air. “Did you see?” he howled, triumphant. “I didn’t cry.”

“You didn’t,” I said, and something inside me unclenched.

When we got home, my wife was at the kitchen table. Her hands were folded around a mug like she wanted it to tell her what to do. She said, “She cried.”

“She should,” I said. “She missed Christmas on purpose.”

“She said it, and it was wrong,” my wife said quickly, like ripping a bandage off a sentence. “But your—” She searched for the right word, found the one that excuses. “—prank—”

“It wasn’t a prank,” I said. “It was a mirror. I made her hold what she refused to see. You think I care if she cries? I care if he does.”

My wife stared at the tree, at a crooked paper snowflake hanging from the bottom branches. She said, “He’s so gentle.” It sounded like a confession.

“Being gentle doesn’t mean you have to stand in the doorway when someone kicks you,” I said.

We were still when the doorbell rang again. This time the knock was sharper. I opened the door and the winter came in first, followed by my mother-in-law in a coat with a collar the size of a small country. Her eyes found my nephew on the floor, layering stickers, and stuck there like a needle that has finally reached the groove.

“Hello,” she said to him, voice careful. He did not look up. He knew that voice in his bones.

She handed me a box—my gift to her returned. “I don’t understand your…gesture,” she said.

“It wasn’t for you to understand,” I said. “It was for you to feel.”

“That’s manipulative,” she said.

“Exclusion is manipulative,” I said. “This is accounting.”

My wife moved between us. “Mom,” she said. “He’s our son.”

Silence stripped the room. I waited for the word to be swallowed or softened. It wasn’t. My mother-in-law blinked as if recalibrating a machine.

“We are having duck and chestnuts,” she said to the air because it was easier than speaking to the boy. “There aren’t enough chairs.”

“I know an antique store that sells more,” I said. “They lock at five.”

Her mouth made the shape of a protest. She closed it. She turned to the boy. She crouched. It took more effort than I expected to watch someone her age climb down to eye level. “What’s your name?” she asked, as if she had not held him as a baby, as if she had not memorized it and decided to misplace it.

He said his name. He said it in that voice children use when they think they are being measured.

“That’s a fine name,” she said. “I’m—” She stopped mid-syllable, no word for what she was that did not break a different promise. “I’m Margaret.”

He looked at her. He frowned, not unkindly. “Are you my grandma?” he asked.

My wife made a sound like something breaking very quietly.

“I can be,” my mother-in-law said, and her voice was almost a question.

“You can be,” he said, as if he were in charge of such things. Maybe he was.

She stood slowly. The coat made her look like a mountain turning into a woman. “We have dinner at three,” she said, to the floor, the wall, the past. “If you want.”

“We already ate,” my nephew said, pointing at a belly that would be hungry again in twenty minutes.

“We’ll be there,” my wife said. “If—if we’re welcome.”

“Bring him,” my mother-in-law said, and the sentence stumbled, but it did not fall.

After she left, my wife sat down. I sat beside her. The tree breathed its small light into the room. My nephew pressed a sticker onto my knee and called it a badge. “For when we go to Grandma’s,” he said.

Part 3

At three o’clock, we walked into a house that always smells like lemon oil and expectations. The living room had too many surfaces that reflected you back at yourself. The table was set the way magazines say you should—silver in tiny armies, crystal like ghosts, plates that scratched if you breathed wrong. A duck glistened under a tent of heat. The chestnut stuffing steamed like a memory.

My mother-in-law stood at the end of the table the way generals stand at maps. Her husband, a tender man who learned long ago the kind of silence that keeps marriages intact, pulled out a chair and then another. He smiled at my nephew like a man finding a stray lightbulb in a drawer and realizing it fits the lamp.

We sat. The chair legs made the normal scrape. I helped my nephew unfold a napkin the size of a pillowcase. He placed the fork where he thought it should go and looked to me for approval. “Perfect,” I said. He beamed.

“Would you like to say grace?” my mother-in-law asked the room, then froze as if knowing the answer would place her on a path she didn’t know if she could walk. My nephew said, “I can,” and bowed his head with the gravity of an astronaut. “Thank you for duck,” he said. “And snow. And moms.” He looked up, corrected himself shyly. “And aunties who are moms.”

My wife cried without moving any parts of her face. My mother-in-law closed her eyes for longer than grace requires.

We ate. My nephew declared chestnuts “crunchy clouds.” Margaret—no one called her that yet; it hung above us like a step we would take later—put two extra on his plate. He ate them with one eyebrow raised because he had learned skepticism somewhere and practice felt good in his mouth.

“Do you like school?” she asked.

“It’s fine,” he said, noncommittal. “They have a reading corner.”

“What do you read?” she asked.

“Books,” he said, the way you answer when you don’t yet trust the person asking.

“I like books,” she said. “When I was your age, I read one under the covers with a flashlight.”

He tested the image, then nodded. “My uncle lets me,” he said, then squinted at me. “Sometimes.”

“Always,” I lied.

Halfway through the duck, my mother-in-law stood, disappeared into the hallway, returned with a small box. She placed it by the boy’s plate. “A gift,” she said, and the word sounded heavy, not because of what was inside, but because of what it had to drag out of her on its way to the table.

He opened it with the ceremony of a person who knows paper has dignity. Inside was a knit hat the color of late blueberries. He pulled it on. It slouched over one eyebrow and made him look like a musician. He said, “Thank you, Margaret,” because he had listened when she told him her name. She flinched, then nodded. “You’re welcome,” she said, and if there was an apology in the room, it was spoken in a language without words.

After pie, my mother-in-law announced a walk. “For digestion,” she said, but I think it was for witnessing, for proof that a thing could occur in the broad, indifferent light of the world and not break. We zipped coats. We stepped onto the sidewalk as the day bruised at the edges. The snow had crusted into the kind that crunches. My nephew held both our gloved hands and jumped between us, an old family trick that feels like flight because someone bigger than you shares their gravity.

At the corner, a neighbor waved. “Merry Christmas,” she called, then peered and said to my mother-in-law, “Is this your grandson?”

There was a pause that felt like the tick of a bomb. My mother-in-law said, “Yes.” It was one syllable. It was a month of labor.

“Handsome,” the neighbor said, and kept walking into her own life.

On the way back, my mother-in-law fell behind and ended up beside me. Her voice lowered the way voices do when people are afraid the truth might hear them. “I don’t know how to do this,” she said.

“Like this,” I said. “Badly, and then better.”

We reached the house. The front steps held the day’s cold like a memory. We stripped off boots and made stacks of damp clothes that would smell like clean later. My nephew collected three candy canes and gave one to each of us like truce flags.

In the living room, the tree leaned a little, not enough to matter, just enough to make you worry if you were a certain kind of person. My mother-in-law walked to the mantle and took down a framed photo: my wife as a child in corduroy with a tooth missing, her arms around a dog with a name I never learned. She held it, then put it back. She said to the boy without turning around, “We have a train set in the attic. Do you like trains?”

He looked at me. I nodded. “Sure,” he said. “If they’re loud.” Then he added, because he has a sense of fairness, “I have to go home at seven. My uncle said.”

“We’ll make the train go faster,” she said, and there was something like joy in it.

Part 4

The next morning, my phone displayed a confession I hadn’t earned and wasn’t sure I wanted: a text from my mother-in-law. I’m sorry. I typed a response and deleted it. I typed another and deleted that, too. A person who has learned to hold power in a sentence needs you to put your apology down somewhere you can’t pick it back up and use it to hit them later. I sent: Thank you for inviting us. Let’s keep showing up.

My wife stepped into the kitchen in a robe with the belt trailing. Her hair had slept hard. She poured coffee and leaned against the counter. “I called the lawyer yesterday,” she said. “To start adoption paperwork. Not because of Mom. Because it’s what I should have done when he put on his shoes in our hallway for the first time and called me Auntie with a question mark at the end.”

I stared at her as if she were a new person with the same face. “Okay,” I said, because sometimes the right answer is a syllable that holds the door open for the rest.

“I want him to be ours in the places that need paper,” she said. “He already is in the places that don’t.”

A week later, the social worker came, a woman with kind eyes and a tote bag full of forms. She asked us about routines and discipline and where he sleeps and what we do when storms make him small. She asked my nephew what his favorite food is (pancakes) and who he talks to when he is scared (Uncle, but sometimes the cow next door because it’s big and calm). She asked my mother-in-law if she wanted to be listed as an emergency contact. My mother-in-law answered too quickly, “Yes,” then softened it with, “If you’ll have me.”

We signed things. We made copies. We learned that families are sometimes filed alphabetically.

In February, the court date arrived like a new pair of shoes—familiar, stiff, necessary. We stood before a judge whose robe made him look like a bell. My sister’s name was spoken in a tone that made me relieved and angry in the same breath. The judge asked, “Do you understand the responsibility you’re accepting?” and I wanted to laugh and cry because who understands responsibility until it is already sitting on your lap asking for a snack.

We said yes. Our nephew held both our hands and swung. The gavel turned our life into law.

After, we drove to a diner with red booths and a menu that didn’t believe in trends. My mother-in-law met us there. She slid into the booth like a person learning how to sit in a new life. She held a bag that looked like it belonged in a hospital gift shop: small, hopeful, a little embarrassed. Inside was a photo—my wife at six, gap-toothed, holding a paper crown and standing between her parents—placed beside a new photo the court clerk had taken on a plastic chair: my nephew between us, paperwork in my pocket, the world slightly more legible. “I had the clerk print two,” she said, “in case one gets…touched too much.”

My nephew ordered a milkshake the size of his head. He said, through whipped cream, “Grandma, can I show you my Lego train sometime?”

My mother-in-law smiled in the exact way a person does when a word they practiced in the mirror finally slips out and lands where it should. “Of course,” she said. “We’ll make it loud.”

Back at our house, I stood in the doorway and looked at the tree we still hadn’t taken down because we wanted the room to keep one soft thing. The paper snowflake drooped. The Lego badge still clung to the lamp. The world looked the same and new.

My phone buzzed. A message from an unknown number. A photo: my mother-in-law’s phone screen, zero missed calls, clean as new snow. Beneath it, she had typed: I understand.

I put my phone down. I let the quiet do its work.

That night, my nephew fell asleep with the knit blueberry hat on, a small star on his hairline where the yarn had pressed. My wife put a hand on his chest and counted with me until our breaths synchronized with his. We lay there, the three of us, a small family arranged like a sentence that had finally found its verb.

In the months that followed, the world didn’t turn kind in general. That’s not how worlds work. But a house learned a new sound. A woman learned a new name. A boy learned that love can be argued with and still win.

Sometimes I still think about the 56 missed calls. When I do, I hear the other thing—my sister’s voice the day I signed the papers: Take him home. That’s all. Just…take him home.

I did. And when Christmas comes again and someone asks if we’re keeping it small—just family—I’ll nod and set three plates and call my mother-in-law to bring the chestnuts. We will make more chairs. We will speak less carefully and mean it more. The train will be loud.

And if the phone rings while we pass the duck, we’ll let it. We’re busy. We’re eating. We’re here.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

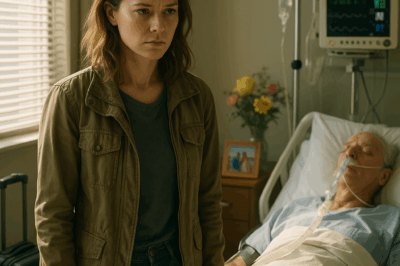

CH2. I CAME HOME AFTER YEARS AWAY – AND FOUND DAD IN A HOSPITAL, ON LIFE SUPPORT. MOM AND MY SIBLINGS…

I came home after years away – and found Dad in a hospital, on life support. Mom and my siblings?…

CH2. Her boss secretly erased her raise — But she built the system that exposed every lie

Her boss secretly erased her raise — But she built the system that exposed every lie Part 1 The…

CH2. My brother jeered my inheritance, saying he’d get the house and dad’s business; until the lawyer…

My brother jeered my inheritance, saying he’d get the house and dad’s business; until the lawyer… Part I —…

CH2. The Irony: ‘Leave!’ They Said, Unaware of My Ownership. The Moment I Revealed the Truth.

The Irony: ‘Leave!’ They Said, Unaware of My Ownership. The Moment I Revealed the Truth. Part 1 “I don’t…

CH2. You’re Being Selfish! Said My Son And His Wife Threw Wine At Me, So I Texted My Lawyer!

You’re Being Selfish! Said My Son And His Wife Threw Wine At Me, So I Texted My Lawyer! Part…

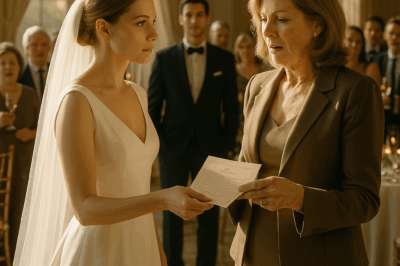

CH2. At My Wedding, Mom Smirked: “It’s Just a Car.” So I Handed Her the Legal Envelope…

At My Wedding, Mom Smirked: “It’s Just a Car.” So I Handed Her the Legal Envelope… Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load