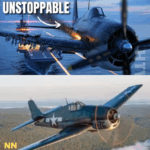

The Grumman F6F Hellcat was America’s answer to Japan’s deadly Zero — and it didn’t just win, it dominated. From the Battle of the Philippine Sea to the final days of WWII, this flying fortress changed the course of the Pacific War. Discover how the Hellcat became the most successful fighter in U.S. Navy history, surviving impossible odds and rewriting air combat forever.

The date was June 19th, 1944, and the Philippine Sea glittered like hammered metal beneath the morning sun. Far above it, a single Japanese Zero dropped from fifteen thousand feet, its pale wings biting into the air as it rolled into a steep, hungry dive.

Inside the cramped cockpit, Lieutenant Haruto Sato felt his heart slowing with the familiar, murderous calm of the attack. Below, an American carrier plowed through the water, white wake trailing behind its great gray hull. To him it looked impossibly slow, impossibly vulnerable, like a giant animal unaware of the spear hurtling toward it.

He tightened his grip on the control stick, the leather of his gloves creaking. The dive was perfect. The angle deadly. He had done this dozens of times in three brutal years of war. Pearl Harbor, the Indian Ocean, the Solomons—always the same routine, always the same result. The Americans would spot him too late. Their fighters were slower, clumsier. Their pilots, he had been told, lacked the spirit of the samurai.

He believed that once.

He trimmed the nose down a fraction more. The carrier swelled in his gunsight. Anti-aircraft bursts began to pepper the sky, dark flowers blooming uselessly behind him.

They still cannot touch me, he thought, a thin smile tugging at his lips.

Then the light in his cockpit flickered.

A shadow crossed the Zero’s canopy—then another, and another. For half a heartbeat he thought it was smoke, or a trick of the sun on glass. Then instinct made him snap his head back, eyes ripping away from the carrier just in time to see it.

A blue-gray fighter screamed overhead, close enough that he could see the white star on the wing and the dull gleam of metal around the big radial engine. It wasn’t a stubby Wildcat. This thing was larger, meaner, wrong.

He had never seen it before.

The American fighter banked hard, rolling into a tight arc above him. Another followed, then another, their wings flashing as they turned. A dozen shapes, then more, all of them converging, dropping from the sky like wolves upon a lone deer.

Panic slammed into him.

He yanked the stick, trying to break left, to roll clockwise into the old, perfect Zero turn that had saved him a hundred times.

Too slow.

The American’s nose dipped. Six gun ports glared dark in its wing. For a ridiculous, fleeting moment, Haruto thought the fighter looked angry—like a fist wrapped around an engine, like a steel animal.

The guns lit up.

Fountains of tracers leapt across the air, a single savage line that connected the Hellcat’s wings to his fuselage. The sound was a distant, vibrating roar through his thin armor plate, more felt than heard. The cockpit exploded in a storm of glass and metal. Instruments vanished. The right wing simply ceased to exist. Fire tore across his vision.

What had been the most feared fighter in the Pacific was, in a second, reduced to burning fragments. Haruto’s last sight of the carrier he’d been about to kill was upside down: a gray deck, sailors running, and above them, a sky filled with American fighters.

The Zero tumbled, trailing black smoke as it fell toward the cold, indifferent sea.

Within minutes, forty-two more Zeros would follow it down. Then one hundred. Then two hundred forty-three, in a single day. The Japanese would call it a massacre. The Americans would call it the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.

The pilots who flew that day knew exactly what it was.

It was the F6F Hellcat doing what it had been built to do.

Winning.

Two years earlier, America had been losing.

The memory of December 7th still tasted like smoke and oil in the mouths of hundreds of thousands of sailors and airmen. Pearl Harbor had been attacked. The Pacific Fleet’s battleships lay twisted and blackened in the harbor’s shallow water. Japanese forces were rolling across the Pacific like a storm, and everywhere they went, their aircraft seemed unstoppable.

In the air, American pilots were dying.

Ensign Jack Mercer had learned that lesson the hard way above the Solomon Islands in 1942, wedged into the narrow cockpit of an F4F Wildcat. The Wildcat had the soul of a bulldog and the body of a refrigerator—stubby, slow, and tough as old boots.

It could take hits. That was the good news.

The bad news was everything else.

“Mercer, check six!” his section leader had screamed in his headphones that day, voice tight with panic.

Jack craned his neck, the world tilting as he strained against the harness. There, behind him, haloed by the glare of the sun, was a shape he had come to dread—a sleek, pale fighter with rising suns painted on its wings and a nose that seemed to float on the slightest whisper of air.

“Zeros at six o’clock!” he yelled, but he already knew he was too late.

The Zero could fly circles around the Wildcat. Faster, more agile, able to climb higher and turn tighter, it seemed less like a machine and more like a predatory bird. In a dogfight, the Wildcat didn’t stand a chance.

American pilots knew it. Every time someone shouted “Zeros at six!” over the radio, the cockpit went cold. That phrase could turn a routine patrol into a death sentence.

Jack slammed the throttle forward, the Wildcat’s engine growling. He tried to dive, but the Zero stayed glued to his tail, its pilot matching his move like a dancer mirroring a partner.

Tracers whipped past his canopy.

He felt the Wildcat shudder as bullets punched through metal. One hit the armored plate behind his seat with a sound like someone striking a church bell. He flinched, then realized, with a savage thrill, that he was still alive.

That was the Wildcat’s one saving grace. It could take punishment.

Zeros were built like arrows—lightweight, almost no armor, designed to move fast, turn tight, kill quickly. A few bullets in the wrong place and they went up like paper lanterns.

The Wildcat was different. You could shoot holes through it, knock out a cylinder, shred the tail, and somehow the ugly little brute would still claw its way back to the carrier, trailing smoke.

That day, Jack dove into a cloud bank, engine howling, the Zero’s tracers sizzling past his wingtips. For several breathless seconds he felt death press close. Then, suddenly, the fire stopped. He punched through the underside of the cloud alone, skimming low over the ocean.

He limped home, hands shaking on the stick, the cockpit full of the smell of oil and cordite. When he stepped onto the deck, mechanics whistled at the holes in his fuselage.

“Damn, Mercer,” one of them muttered, running a hand over a jagged tear in the skin near the tail. “You brought this crate back from the dead.”

Jack didn’t answer. He stared back at the torn sky where the Zeros had vanished and thought, We can’t keep doing this.

Somewhere on Long Island, a man named Leroy Grumman was thinking the same thing.

In early 1942, Grumman’s engineers gathered in a conference room thick with cigarette smoke and urgency. War had a way of squeezing time, of turning “someday” problems into “right now, or else” problems. On a chalkboard, someone had scrawled three words in large, block letters:

BEAT THE ZERO.

That was the mission.

They didn’t just want to match Japan’s vaunted fighter. They wanted to kill it.

Leroy Grumman was not a dramatic man by nature. He was short, practical, with oil under his fingernails and a mind that thought in rivets and load stress. But even he felt the weight of that room. Young men were dying in aircraft that bore his company’s name.

“We keep what works,” he said, tapping the chalkboard, “and we fix what doesn’t.”

The Wildcat’s toughness had impressed everyone. What it needed was everything else.

“Make it faster,” one engineer said.

“Make it climb,” another added.

“Make it hit harder,” someone in the back grunted.

“Make it unstoppable,” Leroy finished quietly.

A murmur went around the table.

They had one thing the Japanese didn’t know about. Something invaluable.

In a hangar thousands of miles away, American intelligence officers had recovered a mostly intact Zero from the Aleutian Islands. It was a battered ghost of an airplane, its green paint flaking, its skin torn. But it was there—an enemy fighter, lying in their hands instead of swooping past their canopies.

They took it apart like surgeons working on a dangerous animal. Engineers crawled through it, measuring spars, weighing armor that wasn’t there. Test pilots flew it in mock combat, learning how it climbed, how it stalled, how it turned.

They discovered the Zero’s secrets—and its weaknesses.

It was fast and agile because it had sacrificed everything else. No armor. No self-sealing fuel tanks. Thin, lightweight construction. It was a glass cannon: deadly if it hit you first, doomed if you ever managed to hit it back.

“So we don’t build a mirror,” Leroy said, watching a test pilot maneuver the captured Zero over the field. “We build its opposite.”

They started with the engine.

In a factory in Connecticut, Pratt & Whitney had a monster of an engine, the R-2800 Double Wasp—eighteen cylinders, two thousand horsepower, a radial heartbeat that shook the ground when it roared to life. They bolted it to the nose of their new fighter on the drawing board and smiled.

“Give it this,” an engineer said, tapping the blueprint where the engine sat. “And it won’t just keep up. It’ll run them down.”

They wrapped the engine in armor and steel. They added self-sealing fuel tanks, heavy plating behind the pilot, bulletproof glass in front. The cockpit would be a fortress.

They gave it six .50 caliber Browning machine guns, three in each wing, four hundred rounds per gun. When all six fired, the sky in front of the plane would become a solid curtain of lead.

They drew wide wings for slow carrier landings and a massive fuselage to house all that armor and ammunition. It wasn’t sleek. It wasn’t graceful. It was a brute in sheet metal, a flying fist.

Someone joked that it looked like it could punch through a brick wall.

“Good,” Leroy said. “Make sure it can.”

The prototype flew in June 1942. Test pilots climbed out of the cockpit grinning, hair windblown, eyes sparkling despite the exhaustion.

“This thing climbs like a rocket,” one said, hands still trembling with adrenaline.

“Dives like a meteor,” another added.

“It’s a truck,” a third pilot declared, then laughed. “A truck that outruns sports cars and carries a battleship’s worth of guns.”

The name they gave it was simple, blunt, and absolutely appropriate.

Hellcat.

By October 1942, the Navy had seen enough. They placed the order, and Grumman went to war in a different way.

The factory lines became a blur of rivets and sweat, of women in coveralls and men who were too old or too essential to be sent overseas. At peak production, they were rolling out a new Hellcat every thirty minutes. A war machine every half hour, metal testimony to American industry and urgency.

Thirty minutes to build a plane. Years of training to build a pilot. And together, maybe, they’d turn the tide.

In January 1943, the first operational Hellcats reached the Pacific.

On the deck of the USS Essex, heat shimmered above the steel as sailors guided the big blue-gray fighters into position. The pilots who approached them were men who had known fear in the Wildcat’s cockpit. They had seen Zeros flash past them like ghosts.

Jack Mercer ran a hand along the Hellcat’s fuselage for the first time and felt something loosen in his chest.

The plane was big, solid. The skin around the engine felt like armor plate. The canopy glass was thick, the cockpit snug but blessedly roomy compared to his old Wildcat.

He climbed the ladder and dropped into the seat, the smell of new paint and fuel wrapping around him.

“How’s it feel?” his mechanic called up.

Jack slid his hands over the controls, feet resting on the wide, sturdy rudder pedals. The instrument panel was arranged logically, everything where it should be, not where some engineer imagined it might look nice on paper.

“It feels,” Jack said slowly, “like climbing into a truck that borrowed a race car’s heart.”

The mechanic laughed. “Just bring it back in one piece, sir.”

When he pushed the throttle forward for the first time on takeoff, the Hellcat didn’t hesitate. The R-2800 roared, and the whole plane surged forward like something alive that had just been let off a chain. The deck blurred under his wheels, then vanished as he broke free of gravity and clawed into the sky.

He looked down at the ocean glittering below, at the shrinking carrier, and thought, This is what it should have felt like all along.

On August 31st, 1943, Jack and fifteen other Hellcat pilots sat in their cockpits on the Essex’s deck, engines rumbling, waiting for the signal to launch. The target was Marcus Island, a dot of land in the vast Pacific, sprouting Japanese anti-aircraft guns and airfields like thorns.

The rumor had already spread through the ready room like wildfire.

The Japanese know about the new plane.

They know its name, someone said. They call it a heavy fighter. Slow.

Let them think that, Jack thought, checking his instruments one last time.

The launch officer’s hand chopped downward. One by one, Hellcats thundered down the deck and leapt into the air. Jack’s stomach dropped as the ocean rushed under him, then steadied as the plane responded to his touch, climbing, climbing, the engine’s song steady and strong.

They approached Marcus at medium altitude, sunlight glinting off the wings. The island appeared ahead, a smudge of green and gray on the horizon.

“Bandits, twelve o’clock. Zeros scrambling,” came the calm voice on the radio.

Jack’s pulse spiked. He scanned the sky and saw them: pale shapes lifting from the island like startled doves, gaining altitude in spirals.

They were beautiful, in a way. Beautiful and deadly.

Back in the Wildcat, this was the moment his gut would have filled with cold dread. Today, as the Zeros climbed to meet them, Jack felt something else.

Anticipation.

“Remember your briefings,” came the voice of their squadron leader, Lieutenant Commander Edward “Butch” O’Hare. “Don’t turn with them. Use your speed, use your dive. Make one pass and get out. Let the Hellcat do what it was built to do.”

The two formations closed.

For a few seconds, there was nothing but the distant glint of wings and the thrum of engines. Then the sky erupted.

The Hellcats dove.

Jack rolled his plane onto its side and dropped, pushing the nose down until the wind howled around the canopy. The Zeros below ballooned in his gunsight, a tangle of wings and palms and confusion.

He picked one and squeezed the trigger.

The Hellcat’s six Brownings spat fire, the recoil vibrating through the wings and into his bones. Tracers walked up the Zero’s fuselage in a single, merciless line. A puff of black smoke blossomed near the cockpit. The enemy fighter snapped sideways and began to fall, pieces shedding from its frame.

Jack didn’t watch it hit the ocean.

He pulled up, feeling the heavy Gs as the Hellcat responded, then rolled again, dove again. Below him, the dogfight broke apart into swirling knots. Zeros tried tight, desperate turns, but the Hellcats refused to follow them into their old dance. Instead, they climbed, looped, dove, striking from above like hammers.

Within ten minutes, eight Zeros were burning or sinking into the sea.

Not a single Hellcat was lost.

When Jack landed back on the Essex, he popped his canopy and sat there for a moment, breathing hard, listening to the engine tick as it cooled. The deck crew scrambled around his plane, fingers tracing bullet streaks along the wings—scratches, nothing more.

O’Hare’s voice came over the carrier’s loudspeakers later, half disbelieving, half exultant.

“I don’t know what the hell we were worried about,” he said. “This plane is incredible.”

Word spread.

On the USS Yorktown, pilots told stories of how the Hellcat could dive away from anything. On the USS Lexington, they bragged that you could shoot the wings full of holes and she’d still bring you home. On the USS Bunker Hill, a pilot swore he’d flown a Hellcat back 100 miles with a cylinder shot clean out of the engine.

Some stories were exaggerated. Many were not.

Across the Pacific, the Japanese began to notice. Reports filtered back to Tokyo: the Americans had a new fighter. It was faster. Heavier. More powerful. And worst of all, it would not go down.

One captured pilot, lean and exhausted, sat in an interrogation room staring at his hands as an American officer asked him about the Hellcat.

“We cannot fight it,” he said finally, shaking his head. “When we see it…” He gave a small, humorless smile. “We run.”

Running didn’t help. Not anymore.

The Hellcat was faster in a dive. It could chase down anything. And when it fired, it didn’t need a long burst. A one-second squeeze on the trigger sent seventy-two heavy bullets downrange—enough, in theory, to kill two Zeros.

By the end of 1943, the Hellcat’s kill ratio stood at thirteen to one.

For every Hellcat lost, thirteen enemy aircraft fell.

No one in naval aviation had ever seen numbers like that.

And the war was far from over.

June 19th, 1944.

The Philippine Sea.

The largest carrier battle in history was about to begin.

On one side of the vast blue plain, the Japanese Navy had assembled a strike force that still looked formidable on paper: nine carriers, over four hundred aircraft, the remnants of a once-dominant air armada.

Their mission was simple and desperate.

Destroy the American fleet.

Regain control of the Pacific.

Reverse the tide before it was too late.

On the other side of the sea, Admiral Raymond Spruance stood on the flag bridge of his flagship and watched the horizon through binoculars. Task Force 58 stretched around him in a steel forest—fifteen carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, a small moving city of gray hulls and black guns.

Below decks, pilots in flight ready rooms waited for the word. Some paced. Some smoked. Some stared at photographs folded into their logbooks.

Jack Mercer sat on a bench beneath a chalkboard listing his squadron’s aircraft, numbers chalked next to names in the easy, gallows humor of combat pilots. He sipped lukewarm coffee and tried not to think about every mission he’d flown that had almost been his last.

On the board, someone had drawn a crude turkey wearing a rising sun headband.

“Too soon,” someone muttered.

“Not soon enough,” someone else replied.

Over three hundred of the planes on those carriers were F6F Hellcats.

When the radar screen on one of the American ships lit up with a cluster of blips seventy miles out, a murmur went through the Combat Information Center.

“Here they come,” an operator said quietly.

The first wave: sixty-nine aircraft—Zeros, dive-bombers, torpedo planes—rose from Japanese decks, their pilots focused on the coordinates of the American fleet. They had trained for this moment, many of them since before Pearl Harbor.

They did not know that their opponents were no longer flying Wildcats.

The order went out.

“Launch the fighters.”

On the Essex, the deck became a controlled frenzy. Sailors sprinted. Tractors moved. Hellcats were hauled into position as crews yanked away chocks. Engines roared to life, coughing smoke that blew back in hot gusts.

Jack strapped in, heart hammering, as the launch officer’s hand rose, held, then chopped down. The Hellcat surged forward, tail lifting, the end of the deck rushing at him—then falling away as he climbed into the thickening sky.

He joined a growing swarm of blue-gray shapes, forming up in loose, lethal lines.

The Japanese pilots saw them coming.

There were so many. The sky ahead seemed studded with blue specks that rapidly resolved into the broad wings and blunt noses of Hellcats. White stars flashed on fuselages and wings in the sunlight.

For every Zero, there were three Hellcats.

“This is… impossible,” one Japanese pilot whispered into the oxygen mask pressed to his face. He had survived Midway, Santa Cruz, the attrition that had chewed through so many of his comrades. He had never seen such numbers.

The Americans didn’t wait.

They dove into the Japanese formation with the cold, practiced fury of men who had been on the defensive for too long and now sensed the turning of the tide.

Hellcats streaked through the bomber groups like sharks through a school of fish. Zeros peeled off to engage, but they were overwhelmed, their turning battles meaningless against the Americans’ speed and discipline.

Ensign Wilbur “Spider” Webb spotted a cluster of dive-bombers lining up on a distant silhouette that could only be an American carrier. He rolled into a steep intercept, the Hellcat trembling with speed, and let the pipper settle on the lead bomber.

One pass. One squeeze.

The bomber erupted in flame, falling out of formation. Webb rolled to pick up another target, and another. The fight became a blur of noise and light. Later, when someone asked him how many he’d shot down, he had to count them in his logbook to be sure.

Six aircraft in seven minutes.

Lieutenant Alex Vraciu, grinning ferociously behind his mask, dove into a different section of the formation, his guns chattering. Planes fell around him. At one point, he chased a bomber down to wave-top level, engines screaming, until his ammo drums ran dry.

He had shot down six planes in eight minutes. He banked away, frustration burning in his chest.

“There were still targets,” he would say later. “I had to go home because I ran out of bullets.”

The Japanese formation disintegrated. Bombers dropped out of the sky trailing smoke, desperate pilots bailing out, their parachutes blossoming below like white flowers against the blue water. Zeros tried to cover them and died under the Hellcats’ guns.

Of the sixty-nine aircraft in that first wave, only twenty-seven made it back. None inflicted a serious hit on the American fleet.

On the bridges of American carriers, officers watched falling specks through binoculars, their faces grim. Victory in the skies meant lives saved below, but it was still death, still young men tumbling into the indifferent sea.

The Japanese launched a second wave. Then a third. Then a fourth.

Each was slaughtered.

Every time, Hellcats rose to meet them, climbing into the sun, diving like hammers, shredding formations before they could reach effective bombing range. Anti-aircraft guns spoke from American decks as backup, chewing apart any aircraft that slipped through the fighter screen.

By the end of the day, over three hundred fifty Japanese aircraft had been destroyed.

American losses: fewer than thirty.

That night, exhausted pilots stumbled from their planes onto oil-streaked decks, uniforms stiff with sweat and salt. Jack slid down from his Hellcat, his legs threatening to give out beneath him. A crew chief slapped him on the shoulder, eyes wide at the victory reports streaming over the ship’s tannoy.

“Well?” the chief asked, voice hoarse. “How was it up there?”

Jack thought of Zeros disintegrating under his guns. He thought of the way some of them had tried to break away and how the Hellcat had simply run them down. He thought of the enemy pilots bailing out into a sea that would never be friendly to them again.

He swallowed.

“It was like shooting turkeys,” he said quietly. “They just kept coming, and we just kept shooting.”

The phrase stuck.

Reporters picked it up. The Battle of the Philippine Sea became known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, the most lopsided air battle in history.

For the Japanese Navy’s carrier force, it was the end.

Their air power was gutted. The pilots lost that day could not be replaced. The aircraft destroyed could not be rebuilt in enough numbers.

From that point onward, Japan would never again control the air over the Pacific.

The Hellcat had seen to that.

In the quiet days that followed, while ships refueled and rearmed and men tried to sleep through dreams full of fire, numbers began to circulate—cold, simple, terrible.

By late 1944, Hellcats had destroyed over 2,500 Japanese aircraft.

Their kill ratio had climbed to nineteen to one.

Nineteen enemy planes downed for every Hellcat lost.

The numbers were staggering, but they told only part of the story.

What really mattered was what those numbers meant to the men in the cockpits.

The Hellcat’s power had given them speed—control over when to fight and when to run. Its protection had allowed them to make mistakes and survive them. Its simplicity had meant that pilots fresh from training could take it to war and come back.

Lieutenant Hamilton McWhorter—everyone called him Mac—had a story that spread from ready room to ready room like a campfire legend.

Over the South Pacific, he had flown into a swarm of enemy fighters, his Hellcat hammered by cannon shells. One 20mm round punched straight through his cockpit armor, missed him by inches, and tore out through the canopy.

He flew home through the rush of wind whipping past the new hole above his head, landed on the heaving deck, and walked away.

The next day, he was in the air again.

Pilots told that story with the same reverence they reserved for tales of aces and heroes. Not because it was glamorous, but because it captured what the Hellcat meant to them.

It was a machine that forgave.

In squadron bars on distant islands, decorated with makeshift signs and pin-up posters, pilots raised tin cups of warm beer and tried to put into words what the new fighter had done.

“Before the Hellcat,” Jack said one evening, staring at the condensation on his mug, “you always wondered, every time you went up, if that was it. If some Zero would come down out of the sun, and you’d never see it coming.”

He glanced around the table at the faces of his friends, some of them barely old enough to drink.

“Now?” he went on. “I won’t lie. It’s still war. People still die. But when I climb into that cockpit… I feel like I’ve got a fighting chance. Maybe more than a chance.”

Across the room, a radio crackled with stateside news. Somewhere a swing tune played low. Outside, beyond the walls, the surf beat eternally against the sand.

The Hellcat’s legacy wasn’t just in its numbers. It was in nights like that, where men who should have died months ago laughed too loudly and promised each other they’d meet back home in bars that didn’t smell like kerosene.

The Hellcat wasn’t the most advanced fighter of the war. It wasn’t the prettiest. It wasn’t even the absolute fastest.

But it was the most effective.

Power. Protection. Simplicity.

Those three pillars defined it.

Power meant that the Hellcat could choose the terms of engagement. The R-2800 engine gave it a top speed around 380 miles per hour, a climb rate that could put it above the enemy quickly, and the ability to reach high altitudes where the Zero began to gasp and fall behind.

Protection meant that hits which would have turned a Zero into a fireball became survivable scars on a Hellcat’s hide. Bulletproof glass, armor plating, self-sealing fuel tanks—all added weight, but also added lives.

Simplicity meant that when a green pilot fresh from training took her into combat, the plane did not punish him for being inexperienced. The controls were forgiving. Carrier landings, while never easy, were as manageable as they could be. Mechanics could swap parts and repair damage in hours instead of days.

In contrast, other Allied fighters, like the Corsair, were faster, sleeker, more temperamental. The Corsair earned the nickname “Ensign Eliminator” for the way it bucked and twisted inexperienced pilots during carrier landings. Eventually, it would find its place as a land-based fighter. Carriers needed something tamer.

They needed the Hellcat.

Back at Grumman, the assembly lines continued to hum. Standardized parts flowed from bin to plane. A damaged Hellcat could land on a carrier in the evening, riddled with bullet holes, and roll off the deck ready to fly again by morning.

This was a war of attrition now. Japan’s factories were being bombed. Its supplies of fuel and aluminum were dwindling. Every Zero shot down was a loss they could not easily replace.

For America, every Hellcat shot down was a tragedy—but behind it stood ten more on carrier decks, twenty more on transport ships, a hundred more rolling down factory floors.

The Hellcat was never designed to win a single perfect duel.

It was designed to win a long, grinding, ugly war.

And that was exactly what the Pacific had become.

In October 1944, above the Philippines, a pilot named David McCampbell woke before dawn aboard the USS Essex. He was the commander of Air Group 15, a man whose calm in combat had earned him the respect of everyone under his command.

By the time the war ended, he would become the Navy’s top ace, credited with thirty-four aerial victories—all in the Hellcat.

On that particular morning, he led his fighters into a sky crowded with enemy aircraft. It was chaos again—Zeros, bombers, American fighters diving and climbing, the ocean below a distant, churning mirror.

McCampbell’s Hellcat danced through the chaos with lethal precision, its guns barking in short, controlled bursts. One, two, three enemy planes fell under his fire. The number would climb. He flew as if the Hellcat were an extension of his own will, its heavy wings as responsive as fingers.

Years later, when he was an old man with a lifetime between him and the war, he would say that he owed every day he lived after 1944 to that big, rugged fighter.

He was not alone in that sentiment.

Thousands of pilots came home because the Hellcat brought them back.

Some came back limping, fuselages shredded, engines coughing. Some landed with control surfaces so chewed up their planes looked like floating scrap yards. Mechanics would shake their heads, pat the battered metal, and say, “We’ll get her flying again.”

And often, they did.

On the other side of the war, in cramped Japanese briefing rooms open to the humid air, surviving pilots stared at maps and listened to officers talk about new strategies.

They spoke of kamikaze attacks—pilots turning their planes into weapons, trading their lives for the chance to smash into an American ship. It was a strategy born not of fanatic glory, but of desperation.

They no longer had the pilots or the planes to fight conventionally.

The Hellcat had seen to that, too.

After the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, Japanese carrier aviation was effectively finished. The experienced aviators who had dominated early battles were gone. Replacement pilots had fewer hours in the cockpit, less training, fewer chances.

When they took off to face Hellcats now, they flew not as hunters, but as men heading toward a wall of steel they could not break.

By August 1945, the Pacific was a different ocean.

Carrier task forces moved where they wished. American fighters swept over Japanese cities and ports, their presence in the sky a grim inevitability.

Above it all, Hellcats flew in squadrons—some on combat air patrol, some escorting bombers, some simply piercing the clouds on training flights, their war nearly over.

On September 2nd, 1945, the USS Missouri lay anchored in Tokyo Bay. On her deck, Japanese officials signed surrender documents that ended a conflict that had burned across continents and oceans.

Overhead, in a sky finally almost free of gunfire, F6F Hellcats circled in wide, lazy patterns.

Jack Mercer stood near a railing, cap tucked under his arm, watching them. The sound of their engines drifted down like distant thunder. He thought of the first time he’d taken off in a Wildcat, feeling slow and outmatched. He thought of Haruto Sato, a man he had never met, who had once dived toward an American carrier believing he couldn’t be stopped.

He had seen, over these years, how wrong that belief had been.

Beside him, a younger pilot leaned on the rail, looking up.

“Think they’ll keep flying those?” the younger man asked.

Jack shook his head. Already, talk was circulating about jets, about a new age of propulsion and speed.

“Not for long,” Jack said. “They’ll scrap most of them. Melt them down. Turn them into cars, maybe. Toasters.”

The younger man laughed softly.

“Seems a shame,” he said.

Jack watched a Hellcat bank, sun flashing off its wings.

“Yeah,” he said. “But that’s the way it goes. A weapon does its job, and then the world moves on.”

The Hellcat had done its job.

It had flown over 66,000 combat sorties. It had destroyed 5,271 enemy aircraft in the air—nearly half of all Japanese planes shot down by American carrier aircraft. It had changed the shape of naval warfare, redefined what a fighter should be, and, in doing so, helped bring an empire to its knees.

It had saved lives, thousands of them, by being tough when it needed to be, fast when it counted, and simple enough that a kid from Kansas or Brooklyn or California could climb into it and bring it home again.

When the war ended, most Hellcats were indeed scrapped. Some were stored in boneyards under the desert sun. A few found second lives as civilian warbirds. A handful ended up in museums.

Every once in a while, decades later, at an airshow on a hot American afternoon, one of those surviving Hellcats would cough to life, its radial engine roaring, the smell of burned aviation fuel transporting gray-haired veterans back across time.

Families would look up as the big fighter took to the air, its broad wings slicing a familiar arc.

To most on the ground, it was just an old airplane making loud noise, a relic of a distant war.

To the men who had once trusted their lives to its thick skin and heavy guns, it was something more.

It was a friend.

It was a promise.

It was the machine that had changed everything in 1944, over a patch of ocean called the Philippine Sea, when one more Zero had dived toward an American carrier and found, instead of easy prey, a sky full of Hellcats—victorious, relentless, unstoppable.

News

HOA Kept Parking Her Porsche Across My Driveway—So I Returned the Favor… Piece by Piece

HOA Kept Parking Her Porsche Across My Driveway—So I Returned the Favor… Piece by Piece Part 1 The shriek…

Dad Slapped Me & Cut Me From $230M Will — Then Lawyers Revealed I Was KIDNAPPED As A Baby

Dad Slapped Me & Cut Me From $230M Will — Then Lawyers Revealed I Was KIDNAPPED As A Baby” At…

My DAD Beat Me B.l.o.o.d.y Over A Mortgage—My Sister Blamed Me. I Collapsed Begging. Even Cops Shook…

My DAD Beat Me Bloody Over A Mortgage—My Sister Blamed Me. I Collapsed Begging. Even Cops Shook… When my dad…

My Parents Gave My Most Valuable Rolls-Royce Boat Tail To My Brother. So I…

When a successful CEO returns home early from Tokyo, she finds her private garage empty and her $28 million Rolls-Royce…

The Aisle Was Empty Beside Me. My DAD Refused — All Because STEPMOM Said I Stealing Her DAUGHTER’s..

The Aisle Was Empty Beside Me. My DAD Refused — All Because STEPMOM Said I Stealing Her DAUGHTER’s.. Part…

I Bought a $1 Million Home 20 Years Ago — HOA Illegally Sold It Without Knowing I’m the Governor

I Bought a $1 Million Home 20 Years Ago — HOA Illegally Sold It Without Knowing I’m the Governor …

End of content

No more pages to load