How One Fighter Ace Outturned 7 Enemy Planes Using a “2-Second Stall” Trick

He pulled the stick hard left and felt the harness bite into his shoulders.

The horizon snapped sideways. Blue and white and a thin line of green jungle spun in a blurred wheel beyond the Wildcat’s canopy. Somewhere above and behind him, seven Mitsubishi Zeros knifed down out of the sun, their 7.7 mm machine guns and 20 mm cannons coughing lines of tracers through the air.

The sky around his cockpit filled with neon threads.

He didn’t have time to count them. Some flashed past the wing root, some stitched under his nose, a few streaked close enough that he saw the tiny red sparks where they burned the paint. The Wildcat shuddered as he yanked the stick, its wings biting into the humid air with an almost audible strain.

They were faster. They could turn tighter. The textbooks and the ready room lectures all agreed: in a turning fight, the Zero wins.

So he did the one thing the textbooks never mentioned.

He cut the throttle.

Not to land. Not to bail out.

To fall.

For two seconds.

His right hand slapped the throttle lever back to idle in one clean, practiced motion. His left hand hauled the stick full aft. The nose pitched up, the prop clawing uselessly at the sky. Wind noise died. The airspeed indicator’s needle dropped like a stone.

Seventy knots.

Sixty.

Fifty.

The stick went mushy in his hand. The Wildcat’s stout wings lost their grip on the air.

The fighter hung for a heartbeat at the top of its own arc like a thrown rock deciding which way to fall.

Then it stalled.

It wasn’t graceful. It never was. The nose sagged, then dropped. One wing tipped, threatening to dip harder into a spin. The whole aircraft shuddered once, like it was offended, and then the world rearranged itself.

For those two seconds, he wasn’t flying.

He was falling.

The Zeros behind him were not.

Locked into the pursuit curve they’d committed to, their pilots riding the Wildcat’s previous turn, they flashed past the point in the sky where he’d been an instant before, guns blazing at empty air. They overshot like sprinters lunging for a finish tape someone had just snatched away.

By the time they realized their target had stepped off the track, he was below them, nose down, throttle forward, dropping through their formation like a stone with claws.

The angles had flipped.

Prey had become hunter.

He didn’t know it yet, not fully—not in the way that gets written up in flight manuals and doctrine—but that ugly, two-second tumble through nothing had just saved his life.

And in the months to come, it would save dozens more.

Spring, 1942.

The Pacific was on fire.

Pearl Harbor was six months cold, the wrecks still bleeding oil into the harbor. Wake Island had fallen. Guam was gone. The Philippines were collapsing under the weight of a relentless advance. Across coral atolls and volcanic ridges, American pilots climbed into fighters built for a different war.

The Grumman F4F Wildcat was tough, stubby, dependable. It could take punishment, bring men home on one engine with half a wing and a prayer. But it was no greyhound.

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero was faster, lighter, sharper. It could claw its way skyward in a climb the Wildcat could only envy and carve turns so tight that American pilots joked you could almost see it bend in the middle.

In a turning fight, the Zero wins.

In a climb, the Zero wins.

Veteran Japanese pilots—the ones who’d cut their teeth over China and roared over Pearl Harbor’s sleeping battleships—knew this. So did the Americans, painfully, by the growing list of names added to base chapels and shipboard bulletin boards.

The carrier decks smelled of salt and fuel and hot rubber. Engines coughed to life in the pre-dawn dark, sending blue exhaust flames over the planked wood. Pilots strapped in, snugged shoulder harnesses, tested stick and rudder, glanced once toward the island or the carrier’s island superstructure, then rolled.

Ready rooms buzzed with nervous energy. Maps pinned to bulkheads showed shrinking blue and expanding red. Intelligence officers briefed enemy formations, headings, altitudes, expected contact times.

No one briefed what to do when you were slower, outnumbered, and alone.

Above the Coral Sea, over Midway, over a place whose name most Americans had never heard before—Guadalcanal—young men learned in seconds what the manuals never mentioned.

Some learned and lived.

Others did not get a second chance.

The lieutenant from Kansas did not look like anyone’s idea of a fighter ace.

He was lean and quiet, the kind of man who blended into the background of group photos. Twenty-four years old, with brown hair that wouldn’t quite stay flat and a jaw that seemed always a little too serious. His hands stayed steady even when the rest of him vibrated with fatigue.

His logbook was thin. Less than three weeks’ worth of combat missions inked into its pages when the war decided to test him for real.

His name would never headline histories. No best-selling memoir, no Hollywood biopic. But the men who flew with him would remember the way he moved in the sky: not with show-off recklessness, not with the kind of daredevil flourish that made instructors shake their heads and secretly smile, but with a kind of quiet logic that looked, from a distance, like instinct.

They would remember the day he came back alone.

His Wildcat smoking, paint shredded, the engine coughing like a chain-smoker starting a run, and seven kills claimed in a single chaotic engagement.

Not because he was faster. He wasn’t.

Not because his guns were bigger. They weren’t.

Because, in the worst two seconds of his life, he chose to stop flying.

And fall.

Years before the war, there was a boy standing at the edge of a Kansas field, squinting up at a fabric-winged biplane doing stall practice above a dusty grass strip.

The garage where he worked smelled of oil and old tires. The flight school next door smelled of avgas and adventure.

He emptied trash, swept floors, then wandered over to the fence whenever he heard engines. In exchange for cheap labor and an extra pair of hands, the instructors let him hang around. When he proved he could hold a chock steady and not faint during a spin, they started letting him ride along.

He watched students practice stalls and recoveries in clunky trainers, the nose pitching up, the airspeed bleeding off, the sudden buffet and drop, the controlled panic as the instructor barked, “Nose down—add power!”

He learned to fly the way some kids learn to read: early, everywhere, on anything with wings and an owner willing to toss him a set of keys. Crop dusters that buzzed over cornfields. Cabin singles that hauled businessmen to regional airports. Rattletrap biplanes that should’ve retired before he was born.

He earned his license at nineteen, flew for a charter service that paid more in experience than dollars, and saved enough to apply to the Navy.

At Pensacola, he was average.

Not the fastest in formation. Not the flashiest in aerobatics. No instructor circled his name and wrote “future ace” in the margins.

They noted his smoothness. His economy of motion.

He didn’t yank the stick. He guided it.

He didn’t chase speed for speed’s sake. He managed energy, trading altitude for knots and knots for position with an intuitive sense that made pattern work and carrier landings look easier than they were.

In a service that still rewarded dash and daring, he was methodical. Forgettable.

He graduated without honors and shipped out into a war that had already eaten the first generation of men like him.

Lexington first. Then, after she went down in the Coral Sea, a new squadron forming up in the steaming chaos of Guadalcanal.

On the island, the nights were hot and close and smelled of mud and mildew and fear. Long after the clatter of mess kits and the murmur of card games died down, a few tents would still show light through their canvas.

In one of them, the quiet lieutenant from Kansas sat on his cot with a maintenance manual open beside him and a notebook on his knees.

Other pilots wrote letters, told stories, teased each other, tried to keep the darkness at bay with noise and cigarettes.

He sketched.

Wing cross-sections. Arcs representing pursuit curves. Angles of attack. Stall speeds at different weights and configurations. He drew the curve that showed lift rising with angle of attack, then dropping off when the wing stalled. He stared at that cliff and wondered.

Instructors had taught stall recovery as a simple, fearful mantra.

Nose drops. Add power. Regain airspeed. Level out.

Students learned it as a mistake to correct. A danger to avoid. The line at the back of the manual with a skull drawn beside it.

He respected the danger.

He also couldn’t stop wondering.

What if it wasn’t always a mistake?

What if, for a heartbeat, falling was useful?

What if you could aim that moment, time it, weaponize it?

What if, in the right hands, at the right instant, a stall could break the geometry of a pursuit the way a judo throw used an attacker’s own momentum against him?

No manual suggested this.

No tactical doctrine discussed it.

So he drew his own diagrams.

And in the Pacific, where doctrine was dying faster than the men who trusted it, thinking on your own was becoming the only real edge that mattered.

The problem, drawn in black ink on a page that smelled faintly of mildew, was simple.

The Wildcat could not turn with the Zero.

Mock combats back at training had shown it. The first real engagements over the Coral Sea and Midway had confirmed it.

Every after-action report that reached the tent city at Henderson Field told the same story.

If you tried to dogfight a Zero, you died.

The Zero’s low wing loading and light construction gave it a turning radius the Wildcat simply could not match. A Wildcat pilot who pulled hard into a turn to shake a pursuer bled speed like a stuck pig. Within seconds he was slower, tighter, and right where the Zero’s gun sight wanted him to be.

The official solution was clear.

Don’t turn with them.

Use the Wildcat’s strengths: diving speed, ruggedness, good roll rate. Boom and zoom. Make one fast pass, fire, then dive away. Climb back later and repeat. Never get into a sustained turning fight.

It was sound advice.

It saved lives.

But advice is written for ideal conditions, and war rarely obliges.

What happened when you were bounced from above, low and slow, with no altitude left to trade? What happened when you were tail-end Charlie on a combat air patrol, covering worn-out bombers limping home on one engine, and the first warning you got was tracers in your canopy?

What happened when there was nowhere to dive to and no one to dive toward?

The manuals didn’t say.

So he sat under the buzzing light of an oil lamp and drew another line.

A curve for the pursuit path of a Zero. Another for the turn of a Wildcat. They intersected like scissors. Predictable. Lethal.

Then he put a gap in his own line. A tiny break.

Two seconds of nothing.

If he could, at the right moment, remove himself from the sky those Zeros expected him to occupy, let them overshoot, then drop back into a new position—

He stopped and shook his head, aware how insane it sounded even in his own thoughts.

It was one thing to sketch it.

Another to do it at 250 knots with bullets in the air.

He closed the notebook, slid it under his pillow, and turned off the light.

There would be time enough to test his theory.

Or there wouldn’t.

Ironbottom Sound got its name later, after too many ships went down and stayed down.

On the morning that mattered, it was just a strip of gray water ringed by jungle and battle smoke, the air heavy with heat and the smell of burned aviation fuel.

Late August 1942.

He was tail-end Charlie in a four-plane division of Wildcats weaving above a returning group of Dauntless dive bombers. The bombers wobbled along in sloppy formation, many scarred from their run over Japanese positions near Tassafaronga. One had a flap chewing the wind, another dribbled smoke from an engine cowling.

The Wildcats stayed close, maybe too close, nervous about leaving the SBDs exposed. Radar back at Henderson Field had reported bogies inbound to the north, but the contact was intermittent, flickering in and out like a bad memory.

The bombers wanted cover.

The fighters didn’t have enough gas to play hide and seek.

The division leader split the difference and kept them at twelve thousand feet over the battered SBDs, eyes scanning the haze.

The call came ten minutes later.

“Bandits high, eight o’clock!”

He craned his neck and saw them.

Seven Zeros in loose V formation, sun glinting off their pale wings, descending fast.

The division leader barked into the radio.

“Break! Break!”

The Wildcats scattered, each pilot hauling his own machine into a defensive turn, trying to deny the attackers an easy target. The neat geometry of the patrol dissolved instantly into chaos.

The Zeros split their formation with the clean fluidity of experience, two sliding left, two right, three dropping straight down the middle. Each picked a target. Each committed.

Within ten seconds, the sky over Ironbottom Sound became a snarling knot of intersecting lines, smoke trails, and curved arcs of death.

He checked his six and saw two Zeros latched onto him like hungry dogs. A third cut across his beam, angling to trap him in a crossfire.

He broke left, jerked the stick, felt the Wildcat’s stubby wings strain. The G-force pushed him down into his seat, gray creeping into the corners of his vision. He kept pulling.

The Zeros followed.

Tighter. Closer.

Tracers zipped past his canopy, little orange needles stitching the air.

He rolled hard right, reversed his turn, tried to extend, but another Zero dropped down out of nowhere to cut him off. He was boxed. Every direction he pointed, there was Japanese aluminum with a red ball on the wing.

He glanced at his altimeter. Too low to dive far. No clouds to vanish into. No friendly fighters close enough to bail him out.

And then, from somewhere so deep in his mind it felt like a voice not his own, a thought surfaced.

The edge.

He slammed the throttle to idle.

The noise of the engine dropped, the prop disc slowing.

At the same instant, he yanked the stick all the way back, feeling for that precise, invisible line where lift quit and gravity took over.

The Wildcat’s nose jumped, then dragged its own momentum uphill. Airspeed unwound.

Eighty knots.

Sixty.

The stall warning horn began to howl, a thin, insistent scream.

He kept pulling.

The controls went soft in his hands, as though the aircraft had suddenly grown old. The stick shook as the airflow separated from the wings, little eddies of chaos replacing the smooth laminar stream.

Then the bottom dropped out.

For two seconds, he was a passenger inside a falling, stuttering machine that had ceased to be a proper airplane.

The Zeros, behind him, were following a different script.

They had committed to his earlier turn, calculating lead, adjusting for his expected speed and rate. Japanese pilots were superb sticks, but they were human. Their eyes and hands and ballistic sights all assumed one thing.

That the enemy would continue to fly.

They rushed through the slice of sky he had just vacated, guns raking a ghost.

From his perspective, hanging in the straps as the nose pitched down and the world went weightless, they shot upward past his canopy, sleek pale bellies flashing close enough to touch, prop discs whirring.

One went so near he saw the pilot’s face, eyes wide behind his goggles, mouth open in what might have been a curse.

By the time that man’s brain processed the missing target, the American had fallen out from under him.

He counted in his head.

One.

Two.

Stick forward. Throttle up. Right rudder to kill a hint of roll.

The Wildcat snapped out of the stall with a lurch, nose down now, speed building. Wind roared against the canopy again. The Gs returned like a slap.

He was below them now.

He rolled the plane on its back, pulled through, and brought the nose up toward the nearest Zero like he was raising a rifle.

The Japanese fighter, overshooting, was climbing shallow, its pilot hauling hard to get his nose back down. For a heartbeat, the Zero’s belly filled his gunsight.

He squeezed the trigger.

Six .50-caliber Brownings spoke at once, the nose of the Wildcat shuddering with their fury. The tracers reached out and walked from wing root to cockpit.

The Zero’s engine cowling exploded in a blossom of fire. A wing tore free, cartwheeling away. The aircraft snapped into an inverted spin, trailing black smoke, then punched into the sea.

Six left.

He didn’t feel elation.

He felt terrified, focused, alive in that weird narrow way that excludes everything except the immediate geometry of survival.

They came at him again.

He did it again.

Throttle to idle. Nose up. Stall horn. Two seconds of falling through nothing. Zeros overshooting, their pilots caught between surprise and training, their beautiful, deadly machines suddenly in the wrong place.

By the time a battered wingman, late to the party and gasping for air, found him again, three more Zeros were burning in the water and another trailed smoke toward distant clouds.

The remaining Japanese fighters, seasoned men who knew survival was its own kind of victory, decided they had seen enough.

They broke off.

He limped home, engine running rough, tail holed, wings scarred, with eleven rounds left in his ammo belts.

On the deck, when he opened the canopy and the cool island air rushed in, his hands started to shake for the first time.

He climbed down the ladder and felt legs that barely remembered what standing on something that didn’t move felt like.

The debrief took an hour and felt like more.

His squadron commander sat behind a battered table, a cigarette burning down between his fingers, listening as the lieutenant described the fight.

It sounded like madness.

“You chopped the throttle?” the skipper asked, frowning. “On purpose?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you stalled her. On purpose.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And then fell under them.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Jesus.” The commander rubbed his face. “You realize we spend weeks telling these kids to avoid stalls like the plague?”

“Yes, sir,” the Kansas lieutenant said. “That’s why they don’t expect it.”

The other pilots crowded in the ready room, shirts half-buttoned, faces still streaked with sweat and grime. Someone muttered, “Crazy son of a…”

“How long were you stalled?” another asked.

“Two seconds,” he said. “Maybe a hair over. Any longer and you risk dropping a wing too far and going into a spin you can’t pull out of at that altitude.”

“How much did you lose?” a third wanted to know. “Altitide?”

“Fifty, maybe a hundred feet, depending on entry speed,” he answered. “You’re trading a little height for a lot of surprise.”

The commander exhaled smoke in a slow stream.

“Walk me through it again,” he said. “Step by step.”

So he did. With chalk on a blackboard, with his hands in the air, with words that turned lift and drag and energy into something the other men could see in their minds.

“This isn’t a trick,” he said. “You have to feel the stall coming. You have to know your airplane. If you’re hamfisted, you’ll spin it in. If you panic and shove the nose down too early, you won’t get the overshoot. If you wait too long, you’ll never get her flying again.”

“At Pensacola, they told us stalls are mistakes,” one pilot grumbled.

“At Henderson Field,” the lieutenant replied quietly, “mistakes are getting shot six seconds later because you did exactly what the guy behind you expected.”

The commander made notes. Another pilot doodled a little sketch of a Wildcat falling through the path of a Zero and labeled it “Kansas Two-Step” with a grin.

By that evening, the lieutenant was scheduled to demonstrate the maneuver for the entire squadron—at altitude, over the relative safety of the ocean, with instructors watching and everyone ready to pull the plug if something went wrong.

They called it the stall turn break at first. Then the two-second stall. The names didn’t matter much.

In those weeks, it was just “that crazy thing he does when they get on him.”

It worked again four days later, when a pair of Zeros came too close over the Tenaru River. It worked a week after that, when he escorted a crippled torpedo bomber home over the Slot and three enemy fighters tried to pick them off.

It didn’t always produce kills.

Sometimes it just produced a miss, a shaken enemy, a few precious seconds of breathing room.

That was enough.

The Navy noticed.

News traveled through channels both official and unofficial, via radio reports and mess hall gossip and the quiet, serious conversations between men who taught others how not to die.

A fighter tactics unit at Pearl Harbor requested a demonstration.

Orders came down.

The Kansas lieutenant found himself pulled off the line, put on a transport, and whisked away from the humid misery of Guadalcanal to the surreal normalcy of Hawaii, where the coffee was better and the hot showers worked most of the time.

He sat in a briefing room on Ford Island in front of a board of senior aviators whose uniforms were crisp and whose eyes carried their own kind of fatigue.

He drew his diagrams on a chalkboard like a nervous schoolteacher.

Pursuit curves. Energy states. The angle at which a pursuer’s closure becomes a liability. The brief, dangerous window where removing yourself from the expected plane of motion flips the script.

Some on the board saw brilliance.

Others saw a headline: promising young pilot augers in trying stunt.

They watched him fly it in a trainer with a second pilot in the back seat, over and over, at different speeds, different entry angles. They grilled him on stall characteristics, recovery cues, danger signs. They argued among themselves.

Reckless, one said.

Necessary, another countered. This isn’t peacetime flying.

In the end, they compromised in the way big organizations do.

The maneuver would be documented and added to advanced fighter training, not as a standard go-to but as an emergency option for experienced pilots.

Use at your own discretion. No guarantees.

The Kansas lieutenant went back to Henderson Field.

By then, his original squadron had flown itself down to a shadow of its former strength. Replacements had come in. Some men he’d shared tents and cigarettes with were gone, their names painted on the side of ammo crates converted into crosses.

The air war moved north and west, then north again. New fighters arrived—Hellcats, Corsairs. New tactics emerged. Radar got better. Japanese pilot quality suffered under the grind of attrition.

The war changed.

But in certain ready rooms, the notebooks stayed open.

The trick migrated, as good ideas do.

Wildcat pilots in other squadrons tried it.

Some loved it, mastered it, swore by it.

Others tried it once, scared themselves half to death, and vowed never again. A few mistimed it, dropped a wing too far, and spun in. War doesn’t give you free innovation.

In the right hands, the two-second stall became just another tool in a growing toolbox: high yo-yos, rolling scissors, slashing attacks, vertical breaks. It was never the only answer. Often, the right answer was still “don’t get into that position in the first place.”

But it changed something more subtle than the kill ratio.

It changed how the Wildcats’ pilots felt about themselves.

Before, facing a Zero at equal altitude, equal energy, felt like stepping into a boxing ring with a faster opponent and one arm tied behind your back.

After, they had at least the possibility of a surprise punch.

Intelligence officers, poring over combat reports, noticed patterns that statistics couldn’t fully explain.

Wildcat loss rates in close-range engagements dipped in certain squadrons, particularly those whose commanders were willing to experiment and whose pilots were given time to practice high-angle stalls at altitude.

VF-5, the unit the Kansas lieutenant flew with before it was chewed up and reconstituted, saw its combat loss rate fall by nearly thirty percent in the six months after the technique became part of its standard repertoire.

Data was messy. War always is. But the trend was there.

More pilots came home from missions they were supposed to die on.

Far away, in the logbooks of Japanese units, another trend emerged.

Over time, Zero pilots became more cautious about pressing attacks on Wildcats that responded unpredictably at close range. The Americans, once seen as clumsy and rigid, began to earn a different kind of respect.

Because the sky had changed.

The Wildcat was still slower, still heavier, but it wasn’t behaving like the rules said it should.

And in a dogfight, predictability kills you faster than any bullet.

The Kansas lieutenant flew fifty-seven combat missions.

He saw friends die in explosions that left nothing but a smear of smoke on the horizon. He saw Zeros fall in burning spirals and felt, uneasily, both satisfaction and something like sorrow each time they went in. He saw ships burn, islands change hands, and the strange, incremental way a war turns when you’re in the middle of it.

He was credited with nine confirmed kills and four probables.

One of those kills was a Zero whose pilot, years later, would be remembered in a different story halfway around the world.

In a village outside Nagoya, a thin, elderly man told his grandson about the day an American fighter had simply vanished out of his gunsight. He described the strange, falling motion, the flash of a blue-gray fuselage dropping like a stone, and the sudden appearance of tracers from below.

“I thought at the time that I had misjudged,” he said. “But now I think he did something I was not taught to expect.”

The old man smiled faintly.

“The Americans were good at that,” he said. “Not always better pilots. But sometimes better at doing something new.”

In mid-1944, the Kansas lieutenant was rotated stateside.

They shipped him east with a group of worn-out pilots and ground crew, their faces tanned and prematurely lined. He felt an odd mixture of guilt and relief stepping off the transport in California, the air cool and clean and smelling of eucalyptus instead of jungle rot.

He spent the rest of the war as an instructor.

In Florida, in Texas, in California, he sat in briefing rooms that looked uncannily like the ones he’d sweated in at Pensacola, now packed with kids barely out of high school.

On blackboards, he drew the same curves he’d once sketched in a tent, but now they had an official name and a training film to go with them.

He taught them the standard stuff first. Formation flying. Gunnery. Basic tactics. Respect for stalls.

Then, with a little smile that only men who’d seen combat really understood, he taught them how to stall on purpose.

He told them, over and over, that this was not a magic escape button, not something you did at low altitude or when you were already out of options.

“This is a tool,” he’d say. “Like a knife. Used right, it can save your life. Used wrong, it cuts your own hand off.”

Some students got it. A few didn’t.

War moved on without him.

By the time Japan surrendered, Hellcats and Corsairs and twin-engine fighters were the sharp end of American naval air power. The Wildcat retired to second-line duties, then to training, then to museums.

The lieutenant went home to Kansas.

The airfield he bought wasn’t much.

Just a strip of grass and dirt carved out of a farmer’s field, a small hangar with a corrugated tin roof, and a shack that served as an office, flight school, and coffee house all in one.

He patched up old Cubs and Champs, taught teenagers and businessmen and farmers’ wives how to take off, land, and not scare themselves silly in between. He wore a baseball cap instead of a flight helmet and carried a pencil behind his ear instead of a sidearm.

Now and then, when the wind was right and the fields were quiet, he’d take a student up to altitude and talk about stalls.

He did not mention Zeros.

He drew no diagrams of pursuit curves.

Instead, he’d climb into a gentle stall, show them the buffet, the nose drop, the recovery, the way you could feel it coming if you paid attention to the airplane instead of the instruments.

“Don’t be afraid of the edge,” he’d say. “Respect it. Understand it.”

If a student wanted to push further, if he sensed the right combination of skill and humility, he might demonstrate something else. A quick, controlled break. A taste of how a brief moment of falling could fit into a larger pattern of control.

He didn’t tell them that once, over a distant strip of water named for the ships that lay at its bottom, he had hung at that edge with seven men trying hard to kill him.

He didn’t talk much about the war at all.

When pressed, usually by someone older who’d read “naval aviator” in his thin, modest obituary, he’d shrug and say he’d just done his job.

He died of a heart attack in 1978, age sixty.

The local paper ran three paragraphs.

Survived by wife, mentioned his airfield, his years of teaching. Noted, almost as an afterthought, that he had served as a Navy pilot in the Second World War.

It did not mention the seven Zeros.

It did not mention the stall.

On a cloudless afternoon, in a small church a few miles from the airstrip, they held his funeral.

Family in the front rows. Townspeople behind them. A pastor who’d known him more by wave than by conversation read the usual verses about running the good race, fighting the good fight.

In the back row, twelve men in their fifties and sixties stood together.

Their hair was gray or gone. Their faces carried the kind of lines you don’t get from sunlight alone.

They did not speak.

They did not need to.

They had all flown with him, or been trained by him, or flown with someone who had. Some had used the two-second stall themselves over Truk, over Rabaul, over nameless little islands no one remembered anymore. Some had passed it on again, to others.

A retired commander among them, his shoulders still carrying a hint of the stiff set of uniformed days, later wrote a letter to the Navy’s historical center.

He described, in clean, clipped prose, the lieutenant’s contributions. The date over Ironbottom Sound. The subsequent demonstrations. The way the maneuver spread. The numbers he’d seen.

He argued that the innovation deserved formal recognition.

The letter was received, acknowledged, filed.

The Navy had newer fighters now. Newer wars. Newer heroes.

The file gathered dust.

But stories don’t live in filing cabinets.

They live in hangars and ready rooms and the corner booths of bars near air bases.

The story of the quiet man from Kansas appeared in memoirs written by more flamboyant comrades, tucked into footnotes, told in U.S. Naval Institute oral histories. The details shifted with memory: sometimes it was five enemy planes, sometimes nine. Sometimes it was over the Coral Sea, sometimes near Tulagi.

The core stayed the same.

A pilot in a bad spot who, instead of panicking, thought.

Who turned a textbook error into a life-saving maneuver.

Who taught others not just what to do, but how to think.

The Wildcats that remain today sit behind ropes in museums, their stubby wings folded, their cowlings polished to a shine that war never left them. Kids press their faces to the glass and talk about how “slow” they look compared to jets.

Docents explain carrier operations, Midway, Guadalcanal. Sometimes, if they know their stuff, they talk about tactics, about how Americans learned to fight a better airplane with a sturdier one.

They rarely mention the two-second stall.

It’s too small a story, too technical, too easily lost amid tales of huge battles and famous names.

But the principle that rode inside those two seconds is still there, in every syllabus, in every cockpit where someone pushes an airplane to the edge of what it can do.

Know your aircraft.

Know its limits.

Know that, properly understood, those limits can become tools.

In modern fighters, with computers helping hold the edge, pilots still train to recognize when the machine is about to stop being an airplane and start being just an object falling through air. They still talk about energy management, about using an opponent’s closure against him, about how a brief departure from normal flight can, if precisely timed, flip a fight.

Most of them have never heard of a garage in Kansas, or a tent on Guadalcanal lit by a single buzzing lamp.

They have never met the lieutenant who drew curves on paper and wondered what would happen if you fell on purpose.

They don’t need to.

His legacy is in the way they are taught to think: that doctrine is a starting point, not a prison. That fear of the unknown is no substitute for understanding. That sometimes, in the worst moment, the right thing to do is the one no manual has written yet.

He never claimed to have changed the war.

He wasn’t the only innovator. He wasn’t the most famous. History is too big, too cruel, to hinge on a single technique sketched in pencil.

But for the men who came home because, in one desperate instant, they pulled the power, hauled the stick back, and chose to fall instead of flee, that isn’t the point.

For them, the war narrowed down to a sky full of tracers, a screaming stall horn, and two seconds of silence where everything could have gone one way and went another.

In those two seconds, held on the knife-edge between flight and freefall, a quiet man from Kansas found proof of something every great pilot eventually learns.

That the edge of control isn’t just a place you avoid.

It’s a place you study.

A place you understand.

And, when everything is on fire and seven enemy planes are closing in, a place you use.

News

CH2. Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming

Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming December 4th, 1944. Third Army Headquarters, Luxembourg. Rain whispered against…

CH2. They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass

They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass The Mustang dropped…

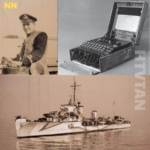

CH2. How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat

How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat The North Atlantic in May was…

CH2. They Mocked His “Too Slow” Hellcat — Until He Outturned 6 Zeros and Shot Down 4

They Mocked His “Too Slow” Hellcat — Until He Outturned 6 Zeros and Shot Down 4 The sky over Rabaul…

HOA Called Cops on Me for Fishing — But The Lake is Mine! They Lost $8.2 Million for Their Mistake

HOA Called Cops on Me for Fishing — But The Lake is Mine! They Lost $8.2 Million for Their Mistake…

“We Don’t Want to See Your Face at Her Graduation” My Mom Snapped During a Family Zoom Call. Then…

What would you do if your family used you until you broke—and then blamed you when you finally said no?…

End of content

No more pages to load