HOA KAREN Called the Cops on Me for LEGAL Open Carry—Didn’t Know I’m the Sheriff!

Part I — Porch Coffee, Patrol Lights

Saturday, 7:42 a.m., and the day still smelled like cinnamon and wet grass. I was on the porch wearing flannel and the kind of slippers my daughter insists will add years to my life. The dogs—two rescues who identify as throw pillows—snored on the welcome mat. It was the hour when Willow Park Estates pretends to be a painting: sprinklers whispering across clipped lawns, cardinals arguing in the crepe myrtle, a jogger counting breaths like prayer.

Three squad cars ghosted around the cul-de-sac.

Curtains twitched. Mail slots opened and closed like fish mouths. The blue-and-red strobes washed across my mug—CINNAMON SUGAR in a font my son tells me is a cry for help.

A bullhorn crackled. “Sir, place the firearm on the ground!”

I looked at the sidearm on my hip, lawfully holstered, right where it had been when I kissed my wife goodbye at the shift change six hours earlier. I set the mug on the porch rail and raised my hand in a small wave, the kind you give friends who just caught you talking to your hydrangeas.

“Morning,” I called.

Recognition dawned on the youngest one’s face like a sunrise punched into fast-forward. He dropped the bullhorn so fast it banged the cruiser door. “Uh—morning, Sheriff.”

Neighbors’ heads tilted in unison. I could feel the recalibration.

My name is Reed Calder, and I am the sheriff of Dry Cedar County. I work quiet, live quieter. Since moving into Willow Park six months ago, I have kept my lawn at regulation height, waved when taking out my trash, and declined every invitation to “connect in the app.” My neighbors either don’t know what I do or pretend not to. I don’t mind either way. Tell people you wear a badge, and they either confess their 2007 sins or ask for free escorts to concerts. I’d rather be known as the man whose rosemary actually thrives.

Enter Gloria Penfield. Self-elected ruler of Willow Park Estates. President of the HOA, chair of three subcommittees that should not exist, wearer of a sash that says as much. The woman has enough laminated paper to insulate a shed. She is the vigilante of vinyl siding.

Her last decree—a hot pink flyer in Papyrus font slid under my door at 11:03 p.m.—declared the subdivision a “Weapons-Free Sanctuary.” She stapled matching signs to the hundred-year-old oak in the common area with such zeal the tree now looks vaccinated. The flyer quoted Gandhi and a home-decor blog in the same paragraph. Somewhere in the bylaws she invented a shadow ordinance and used it to measure my flag pole’s shade at noon, claiming it violated Section Imaginary, Paragraph Why Not.

Gloria patrols at dawn in a golf cart fitted with a dash cam, a police scanner she should not own, and a Bluetooth speaker that plays Swan Lake on loop. The music follows her like a weather report you can’t turn off. She documents recycling bins at six angles, narrates into her phone in a tone that makes David Attenborough’s sound like gossip. “Here we see the non-compliant homeowner in his native habitat…”

Last Tuesday, she’d pounded my storm door at 6:00 a.m. with a “Voluntary Compliance Opportunity,” which turned out to be a form promising I’d never wear my service weapon on my own porch again. It had a watermark of her face.

I told her—politely—that state law doesn’t bend for HOA letterhead, however glossy. She stared at my badge on the hallway table like it was a Halloween prop, then whispered “Rules are rules” as if casting a hex. Her sash fluttered as she spun. If she could fold a fitted sheet with a glance, she would choose violence instead.

So when the bullhorn barked, I knew who had dialed 911.

Gloria stood in the center of the cul-de-sac, reflective vest blinding, hair helmet-perfect, breathless with indignation. She pointed at me like a weathervane in a tornado. “That man is brandishing a weapon in public while threatening the HOA!”

The rookie with the bullhorn moved it behind his back, suddenly interested in the hydrangeas. Deputy Martinez—two months promoted, good nerve, better instincts—kept her face arranged in that neutral geometry the academy drills. Deputy Chin’s shoulder camera caught it all: Gloria’s dash-cam still recording from her patrol, the trio of cruisers, and me, mid-sip and mid-sanity.

“Morning, Ms. Penfield,” I said. “Care to explain the emergency?”

“Emergency?” she sputtered. “You are the emergency!” She waved a laminated copy of a bylaw she’d printed last night. “Section—”

“Section 612.2 of the Virginia Code says otherwise,” Martinez said gently. “Open carry on private property is lawful here.”

“Your ‘law’ does not supersede our community standards,” Gloria declared. “Federal supremacy—of HOA covenants!” She said it with the confidence of a person who once skimmed an article about the Supremacy Clause and then followed a link to a Nextdoor post.

Chin cleared his throat. “That’s…not a thing.”

I held out a hand for her dash cam. “Let’s roll it back,” I said. The screen showed her golf cart circling my house at 7:05, Swan Lake thin and tinny through the speaker, her voice rehearsing her 911 call three times for maximum histrionics. She mimes me brandishing while I water the rosemary with my off hand. The camera on my porch, synced with dispatch time stamps, shows me sitting, mug to mouth, not moving outside of turning a page. It shows Gloria taping her Weapons-Free sign to my storm door at 2:14 a.m., her reflection a smear in the glass, the dogs’ ears lifting in disbelief.

Chin’s body cam caught the moment the rookie recognized his sheriff, recorded Martinez’s eyebrows when Gloria said “federal HOA supremacy,” preserved for posterity my slippers—bunny-eared pink, a gift from my daughter that no man can wear and be taken as a threat, unless the threat is to monochrome masculinity.

“Dispatch,” I said into my radio, “what’s the incident number on this?”

A voice crackled back. “DR-24-1119.”

“Copy. File a false-report complaint and a trespass warning. Add code enforcement to my to-do list.”

Gloria tried to pivot mid-tirade. “You can’t do that. I sign your paycheck.”

“You absolutely do not,” Martinez said, before she remembered to keep her voice neutral.

Neighbors had gathered in clumps that look like friendship until the lawsuits start. The Vietnam vet who maintains the flag at the common area gave me a nod and tapped his cap. The retired schoolteacher from lot 12 positioned herself between Gloria and the children perched on their scooters, a stance born of fire drills and common sense. From behind a curtain I could see the unmistakable gleam of a phone catching everything in 4K.

“Ms. Penfield,” Martinez said, “you are receiving a formal trespass warning. If you step onto Sheriff Calder’s property again, you will be arrested. If you call 911 for non-emergencies, you will be charged. We’ll also need to talk to you about operating a scanner without a license.”

“Rules are rules,” Chin added, deadpan. “Real ones.”

Gloria’s mouth opened and closed like a mailbox that just mislaid a letter. Her sash fluttered in a breeze that did not exist.

The cruisers idled down. The blue-and-red strobes dimmed. The dogs sighed and headbutted the door for ear scratches. The cul-de-sac exhaled.

“Coffee?” I asked the rookies.

“Please,” Martinez said.

Gloria drove away to the sound of Tchaikovsky and the grinding of her own molars.

Part II — The Meeting

The HOA clubhouse smelled like vacuumed carpet and inexpensive salvation. At 7:00 p.m. the folding chairs filled faster than the donut tray emptied. Item fourteen on the agenda, buried between “Gazebo repainting” and “Holiday lawn inflatables,” was Community Safety Initiative.

I wore jeans and a polo shirt. The county attorney, a man whose suits look tailored by someone who has opinions about lapels, sat beside me with a laptop and a smile that meant the PowerPoint had been polished.

Gloria banged the gavel like it owed her money. “Order! As you all know, a grave incident occurred Saturday—”

The attorney stood. “We’d like to begin with some audio-visual context.”

Slide one: the 911 call, timestamped. Gloria’s voice crescendos into hysteria as she uses the word brandishing incorrectly five times. Slide two: my doorbell footage. I do nothing more criminal than scratch my dog behind the ear and reach for my mug. Slide three: Gloria’s dash-cam, in which she rehearses and films herself affixing a sign to my door at 2:14 a.m. while narrating a nature documentary about “aggressive landscaping.”

A murmur rippled like wind through wheat. The Vietnam vet raised a hand. “If my Purple Heart counts as a violation of your weapons-free thing, should I turn it in?”

Silent—the retired officer from lot 22—leaned forward. “Is my concealed permit now contraband? Or am I just welcome during Christmas caroling?”

Gloria tried to gavel the room into submission. The head of the gavel separated, sailed gracefully, and landed in the punch bowl. People did not laugh; they carefully did not laugh. The attorney’s mouth quirked, then stilled.

Slide four: line items from the HOA’s expense account. Artisanal stapler, three hundred dollars. Bulk order of decals, nine hundred dollars, billed as landscaping improvements. Sash, sixty-two dollars. Custom watermark, forty-eight dollars.

Slide five: the portion of the bylaws that require annual legal review of any proposed safety policy changes. “No such review was sought,” the attorney said. “Nor could such a policy trump state law. There is no federal supremacy of HOA covenants. That phrase is not a thing.”

Slide six: the county code enforcement letter re: unlicensed scanner usage, trespass warnings, and the fact that the oak in the common area is now medically stapled.

A hand rose from the back—Marge, who runs a daycare from her home and is the only reason Halloween functions. “Can we just…not do this anymore?” she asked. “The children don’t like Swan Lake at 6 a.m.”

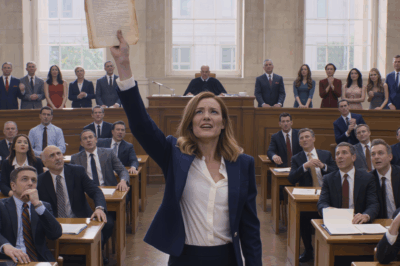

The board huddled. The homeowners whispered. The vote to remove Gloria as HOA president was unanimous, except for Gloria herself, who voted no with a dignity that would have been more convincing if she were not wearing red punch across her blazer.

Then the county attorney, with the dry pleasure of a man who does crosswords in ink, listed charges: filing a false police report, criminal trespass, and misuse of emergency services. Gloria’s face went through the stages of grief so rapidly that even the PowerPoint could not keep up.

Within a month, she’d pled down to two misdemeanors. The judge ordered community service—three hundred hours, split between a civics course and sanitation detail at the county fair. She failed the civics test twice and can now recite the First Amendment with reasonable accuracy. The court mandated a firearm safety class taught by my range master. On day one, he made her say trigger discipline is not the same as lawn discipline. She learned.

The HOA’s insurance sent her a letter. The deductible for her antics—not criminal defense, but the civil defense due to the suit my neighbor filed after she stapled the oak—would not be covered. “Being an idiot is not an insurable event,” the adjuster told the board in a line that I will cherish longer than my pension.

Gloria’s real estate license was suspended for six months. Listings vanished. Her golf cart went silent. The subdivision exhaled like a long-held breath.

Part III — Aftermath

I did not tell this story to gloat. Entitlement is not defeated by victory laps. It is managed by precedent and paper.

A week after the meeting, a letter arrived in my mailbox, hand-delivered. The handwriting was careful as a child’s. Sheriff, it began. This is Daniel from lot 15. I am eight. Thank you for making my mom less scared. Also please tell the lady to stop measuring our shadow. We cannot control the sun.

I put the letter on my fridge beside a drawing of two dog-shaped clouds and a sticker that says please knock nicely, we live here too.

Mark—the neighbor with the Ring camera—started a group called Responsible Adults Who Like Quiet. We trimmed a hedge for the widower at lot 7. We put up lights at the gazebo that don’t flicker like an interrogation room. The Vietnam vet taught the second graders how to fold a flag properly. Marge ran a lemonade stand that somehow paid for two bike helmets and a set of reflectors.

One morning, I found Gloria at the mailbox, hair unarmored, no sash. The cut on her hand from a staple looked like a comma. She met my eyes and said, “I was wrong.” It is not every day you hear that sentence from a person who once invented a shade ordinance to yell at your flag. “I thought safety meant control,” she said. “I thought rules were a war you win.” She blinked hard. “Also, I don’t actually like Swan Lake.”

“None of us do,” I said. “You can stop torturing Tchaikovsky.”

We stood there in the ordinary silence that follows necessary apologies. A dog barked. A kid shouted “Watch me!” at a man who wisely did. A woman in a hijab walked her toddler past us, and the toddler waved in the manner of sovereigns. Gloria waved back.

A month later, she showed up at the community service table at the fairgrounds. She handed out trash bags with the gentle authority of a redeemed camp counselor. She asked the range master questions and listened to the answers. She took the civics exam a third time and passed. She came to a board meeting with a motion written in a clear hand: 1) no more unilateral policies; 2) no more music at dawn; 3) free lemonade for the sanitation crew.

It passed.

Part IV — The Quiet That Stays

I still drink coffee on my porch. Sometimes I wear the slippers. Sometimes my daughter visits and reminds me that longevity is a mental state and also a vitamin. The rosemary grows. The hydrangea blooms like a shy debutante. On Saturdays, the cul-de-sac makes its own weather: chalk drawings, scooters, a teenager practicing scales. The sprinklers still gossip from house to house, but they use indoor voices.

Every now and then, a stranger on a bike slows and asks if I’m the sheriff. I say yes. They ask where the sheriff’s office is. I point at the dogs, the porch, the kids on scooters, the man picking up after his hound, the quiet gathering in the thickness of 8:00 a.m. I say: parts of it are here.

Here is the thing I learned, or relearned, because the badge had said it to me for twenty years in a hundred fonts: law is not a weapon you wave to make the world kneel. It is the scaffolding you build so people can live beside each other without losing their breath. It is the shape that lets even the loud ones learn to be less so. It is the thing you put between a person and her worst instincts. It is the gavel that falls into a punch bowl and becomes a joke only after paperwork has done its work.

One evening, as the sun went down and the cul-de-sac turned the color of a slow trumpet, Deputy Martinez walked up my path with a gift bag.

“From the squad,” she said. Inside, a mug. SHERIFF, it read. Underneath, smaller: PLEASE DON’T MAKE IT A WHOLE THING. My daughter had ordered it.

Martinez sat on the steps. “We still getting calls?” she asked.

“Fewer,” I said. “More emails, less exclamation points. She learned the difference between her feelings and a felony.”

“Good,” Martinez said. “Also, your rosemary is out of control.”

“Write me up,” I said.

We sat and listened to the neighborhood breathe. At 7:42 p.m., a garbage truck rumbled past, two hours late, not a disaster. No one called the cops.

Part V — Endings That Aren’t

The county attorney sent me an email six months later. Case closed, it said. He added a single line: Sometimes the law is just the part of the story that lets the rest exist.

In my office, between the map of Dry Cedar County and the framed photograph of my academy class, I taped three things to the wall.

One: a printout of the false-report statute with the part highlighted that says intent matters. Two: the letter from Daniel, age eight, little sun drawn in the corner like hope. Three: a watercolor someone left at the station anonymous—Gloria in profile, hair down, the golf cart behind her now a wagon full of lemonade.

People ask sometimes if I regret not trying to handle it without the law. They imply lions and lambs and second chances. I tell them I gave one. It came on hot pink paper. It said voluntary compliance. My answer was cinnamon coffee and silence. Her answer was a bullhorn. The law was the piece you call when the volume dial can’t be reached.

There’s a joke at the department now: Sheriff’s HOA policy—no Swan Lake before sunrise. There’s a truth under it: Don’t mistake someone’s porch for your podium. Don’t confuse your lamination with authority. Don’t call 911 to win an argument. Don’t use the word brandishing if the only thing being raised is a coffee mug and the neighbor’s blood pressure.

On the first anniversary of the morning the cruisers rolled in, I got up at 7:40 a.m. and stood on my porch with my mug. The dogs pressed their warm sides into my ankles. The cul-de-sac did its ordinary miracle. No one’s curtains twitched. No lights flashed. Sprinklers whispering, cardinals arguing, a jogger counting breaths. My phone buzzed—a text from Gloria.

Block party at five, she wrote. Lemonade. No Swan Lake. Rules are rules.

The quiet that followed was not empty. It was full.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Dad and “Deadbeat” Brother Sold My Home While I Was in Okinawa — But That House Really Was…

While I was serving in Okinawa with the Marine Corps, I thought my home back in the States was the…

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash Part 1 The scent of lilies and…

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court…

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It Part 1 The email hit my inbox like…

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”?

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”? Part 1 The email wasn’t even addressed to me. It arrived…

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last Part 1 The…

End of content

No more pages to load