HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside

Part I — The First Citation

The morning the first citation bloomed on my screen door like a poisonous flower, the lake was doing that trick it does where it turns the world into an impressionist painting. Mist on glass water. Loons stitching the quiet with their threadbare song. Pop’s dock creaked the way old things creak when they’re proud to still be here. I had coffee in a chipped mug that said CLEAR WATER LAKE FISHING DERBY 1988 and nothing in my head more complicated than whether the walleye were biting at the coves by Cedar Point.

Then I heard the staccato click of high heels on wood.

You don’t expect designer heels at dawn on a lakeside dock built by a man who considered a tie formalwear. You expect boots. Bare feet. Maybe flip-flops with sand ground into the straps. But click click click came anyway, echoing down the planks like an announcement: civilization has arrived and it brought a can of aerosol fragrance.

She didn’t knock. She taped the paper like she was marking a crime scene, smoothed it with the flat of her palm, and took a picture while her Escalade idled in my driveway with the license plate RULE 1 gleaming at the sun. The perfume traveled ahead of her like a threat—sweet and sharp and fundamentally dishonest.

“Good morning,” I said.

She didn’t turn. She posed. “It’s President Cromwell,” she said, as if I’d asked, as if it mattered. “Lakeside Estates.”

“Marcus,” I said. “Henley.”

“I know who you are,” she said, and her smile told me that wasn’t good news.

Delilah Cromwell had arrived in our sleepy tangle of cabins like a tornado wearing a blazer. Somewhere in California, a cul-de-sac was missing its queen. She’d been president of our HOA for less than eight weeks and already had a logo, a tagline, and a mission statement she repeated like scripture: “stewardship, safety, and upscale vision.” Most of us had bought cabins, not a brand identity. She found that barbaric.

I pulled the paper off my screen, the white fibers tearing where the tape was too aggressive.

VIOLATION CITATION, it announced in a font that tried too hard. Unsightly dock structure damaging community property values. Fine: $500. Compliance required within 72 hours or daily penalties will accrue.

I read it twice. Looked past it to Pop’s dock—the one we’d reinforced the summer I turned twelve, him showing me how to sink pilings straight even when the lake wanted you crooked. He’d painted the railings himself, then hand-carved fish into the posts while the stain was still tacky. The dock had greyed into its skin the way bones grey into age. I loved it the way you love a scar that saved your life.

“Ms. Cromwell,” I said, following her onto the porch, “my property predates the HOA by about forty years.”

“Everyone on this lake answers to me, sweetie,” she said, not looking up from her phone. “Ask the Hendersons how well fighting me worked out for them.”

The Hendersons, who’d kept the cabin on the west inlet since the seventies, had “decided to downsize” last month two weeks after a flurry of mysterious citations for “safety hazards” turned their mailbox into a printer. Fifty years of summers baked into their walls and suddenly their deck was a menace. Suddenly their children were urging them to sell. Suddenly a mysterious cash buyer slid into escrow like a shadow.

Delilah circled, snapping pictures with the flat disapproval of a real estate agent herding a house into shape. Solar panels: click. The raised beds where my tomatoes broke ground each May: click. Pop’s carved railing: click, her nose wrinkling like she’d smelled bait.

The first letter was followed by two, then five. Solar panels visible from lake. Vegetable garden interfering with community sightlines. Noncompliant flagpole. Outbuilding paint shade outside approved palette. Each one came with a fine and a deadline and the kind of language that makes decent people apologize for breathing.

It would have been funny if it wasn’t on my door.

I did what Pop taught me when a man with a smooth tie tells you a rough truth: I got my hands on the actual paper. The county clerk’s office smells like old ink and dried leaves, and the woman behind the counter shuffled card-stock history with the affection of a librarian. Betty remembered Pop. Everyone who mattered did.

“That man could tie a Palomar knot behind his back,” she said, pushing a plat across the counter. “What are we looking for, Marcus?”

“Pop’s kingdom,” I said. “The real borders, not the ones with monograms.”

She slid me surveys like a dealer sliding aces. And there it was, in thick black: not just to the waterline. Fifty feet into the lake. The deed from 1963 put my property out past where Pop liked to anchor when the fish were hiding and he wanted to pretend we were working. The HOA hadn’t existed until 1998. Grandfathered rights carry weight in courtrooms and kitchens.

“Keep those dry,” Betty said, like I might jump into the fountain on the courthouse lawn.

I drove home with the paper on the passenger seat, a tool familiar and heavy. The Escalade was in my driveway again, parked sideways like a blockade. Delilah rolled the window down two inches, enough to make a point without letting the world in.

“Oh, Marcus,” she sang. “I’m just reviewing the community parking regulations. This might take a while.”

“You’re blocking my drive,” I said.

“Educational purposes,” she said, and smiled a smile that made me want to wash my hands.

The neighborhood changed with the speed of gossip. Men I’d rigged lines for crossed the road when I walked. Women who’d borrowed flour from Pop when the creek washout kept them from town suddenly pretended their dogs needed disciplining when I passed. The Lakeside Beautification Committee sprouted like fungus—women in linen hats measuring yards with judgement, photographing wind chimes like contraband. Delilah did interviews on channels that love a headline with “protecting values” and used my dock as the backdrop for her concern.

In the middle of the night, someone spray-painted COMPLY OR LEAVE across my mailbox in a shade of orange you only see on prison jumpsuits and traffic cones. My solar camera caught a pearl-white Escalade idling at the end of my drive at 2:31 a.m. The license plate gleamed. RULE 1.

When I called the sheriff, the deputy who showed up was named Cromwell. Chad. He looked at the paint and shrugged, the way men shrug when they learned to be men from men who don’t clean up after themselves.

“Probably kids.”

“Your aunt’s car,” I said.

He tapped something into his tablet that had nothing to do with what I’d just said. “You know, Mr. Henley, if you brought the property into compliance–”

I wished him a good morning. The word “good” hurt my teeth.

Things that look like accidents aren’t. The building inspector arrived with an apology too big for his clipboard. Dale’s a good man who knows when he’s being used. He checked everything Pop built and everything I’d added. He wrote me up a clean bill of pride and said he’d see me at the derby. Then the environmental officer came to test my well and left saying her kids still talk about the knot-tying Pop taught them in fourth grade. Then the fire marshal checked my solar install and asked if the union still did apprentice dinners.

Someone tried to use the machinery. The machinery shook its head.

Then Delilah tried a different machine: the internet. Concerned about aggressive behavior, she wrote on a public Lakeside Strong group. Keep your children away from the eastern shore. We are filing for protective measures. The comments hummed with that particular pitch of fear masquerading as virtue. Names I recognized posted things I knew they didn’t write. Bots ate lies and excreted narrative.

She filed for a restraining order. Judge Harris, who’d fished with Pop when I was little, read the petition and raised one eyebrow high enough to count as a ruling. Motion denied for lack of anything resembling reality. But on paper, my name and the word THREATS flirted for a while. Paper gets into places your voice can’t reach.

If you want to know who owns you, watch who you’re afraid to fight. I started a log. Dates, times, names, badge numbers, citations. I built a map of harassment the way I used to build electrical grids: with redundancy and patience. When true power doesn’t feel inclined to help, use the power you can gather in a basement. People who loved Pop came by with coffee and ugly truth.

“Her husband,” Tom Martinez whispered, eyes scanning the tree line as if the pines were dirty. “Treasurer at the capital. Knows where every dollar wants to go.”

My friend Chuck, who wears the same grin now he wore when he stole the principal’s keys in tenth grade to liberate final exams, put a file on my kitchen table and took out a pen. “The attorney general’s office is investigating HOA corruption cases statewide,” he said. “Patterns like this,” and he tapped my log with his pen—“harassment, lowering values, cash buyers—match what they’re seeing. They need a witness with documents. They need a man who knows how to build a case the way he builds a dock.”

We turned Pop’s spare room into a war room. Maps with thread. Post-its like fall leaves on a wall. Citations in stacks the size of a Sunday newspaper. I learned more about HOA tax requirements in a week than anyone should. Betty at the clerk’s office handed me financial filings with a look that said I may be a clerk but I know a snake. Form 1120s missing. A landscaping company incorporated three weeks after Delilah became president, paid thousands. An “improvement fund” with an account number that tasted wrong when I said it out loud.

Storm claims that didn’t match weather reports. Assessments for “dock repair” when the only dock being abused was mine. Checks written by elderly hands that had no business writing checks, cashed by companies that shared phone numbers with Delilah’s brother-in-law. It was like finding a wire buried in a wall that shouldn’t be hot and tracing it to a fuse that shouldn’t exist.

We called the attorney general’s office. They sent two prosecutors with eyes like tools and a case agent from the FBI who made a map on my table with her finger and pressed down on places that didn’t look important until they were.

“This is systematic,” Agent Torres said. “Organized. You give people like this a title and a bank account and they think they’re invisible. They forget paper has a memory.”

They asked for one more thing: Delilah catching herself on camera. “Criminals under pressure narrate their own crimes,” the younger prosecutor said with the grim cheer of a man who had sat through too many depositions and learned to enjoy the inevitable. “She wants an audience. Let’s give her one.”

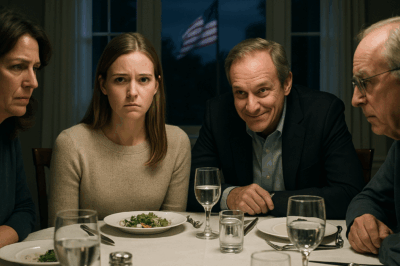

We planned what they called a controlled confrontation. Background checks. Warrants. Hidden cameras tucked under Pop’s porcelain loon and the jar of screws he kept on the mantel like a totem. Law enforcement stashed behind the woodshed where Pop had taught me to whittle and not give myself stitches. Undercover cars down the road. A tow truck idling behind a maple. The attorney general herself, Patricia Williamson, scheduled to sit in Pop’s recliner at 9:00 a.m. on a Tuesday and drink the coffee he used to brew extra strong when we had company.

We planned our bait: an announcement about HOA reform legislation. We whispered it into the places Delilah liked to listen, watched it bloom in the corners of the internet that mistake outrage for wisdom. We watched her live stream settings change to “public.” We watched her add hashtags about corruption and Justice with a capital J. We watched her coordinate with a blogger network that pretends to hate government but loves clicks more, promising exclusive footage of “an illegal meeting between the AG and a known harasser.”

It felt like waiting in a deer stand, except the deer was a woman in a blazer who thought the world owed her obedience and the rifle was paperwork.

Part II — The Door

Attorney General Williamson arrived in jeans and boots that understood pyracantha thorns. She sat in Pop’s recliner like she belonged there, because justice does, and took out a notebook while the lake did its morning glitter. We talked about audits. About mandating independent financial oversight for HOAs that collect more than a certain amount. About criminal penalties for using a citation regime as a cudgel. About whistleblower protections that wouldn’t require men like me to sacrifice peace for truth.

“Mr. Henley,” she said, and the way she said it felt like a compliment Pop would have liked. “We’re going to fix this. Not just for you.”

We heard the Escalade before we saw it. Gravel spit from under tires like anger. The sound of a car door disrespected. Voices on a porch rehearsing outrage and framing it as courage. Delilah’s voice: “Three… two… go. And we’re live.”

She kicked the door.

People who have never kicked a door think it’s glamorous. It’s mostly splinters and mistake. The frame held Pop’s wood longer than her ankle wanted it to, then gave with a sound that made me flinch like I used to when a line snapped under tension. The door swung in. The phone she held in front of her like a torch kept broadcasting.

“I demand to know,” she cried, the way a woman cries when she has attorneys instead of friends. “Why the attorney general is secretly meeting with this man. This is a conspiracy to target my family. This—”

Patricia Williamson stood. Took out a leather case that held identity like a weapon. Held it at chest level. “Mrs. Cromwell,” she said, like a headmistress tired of repeating herself. “I’m Attorney General Williamson. You’ve just committed multiple crimes. And you’re broadcasting them.”

The live chat blinked. The comments slowed, then sped the other direction. Some of them pivoted mid-sentence like fish on a hook. RULE 1 flashed across the bottom of a screen as Delilah’s carefully curated follower list watched the backstage version of the brand tear its costume off.

Agent Torres stepped into my living room flanked by two federal agents who looked like men who eat paperwork and burp case law. “Mrs. Cromwell,” she said, crisp enough to cut, “you’re under arrest for fraud, extortion, witness intimidation, criminal harassment, and unlawful entry. You have the right to remain silent. I recommend you learn how.”

The handcuffs did their little music. Delilah’s phone hit my floor. The Escalade’s vanity plate looked especially stupid being towed, like a dog collar after the dog remembered it was a dog. My neighbors—some sheepish, some gleeful, some both—stood on my porch pretending not to be there. Mrs. Patterson cried into a tissue like a woman who got her kitchen back. Deputy Chad arrived in time to watch his aunt go somewhere he couldn’t follow with a badge.

“You don’t know who you’re dealing with,” Delilah howled as they walked her across Pop’s dock. The dock creaked like a satisfied old man.

“We do,” I said, stepping behind Agent Torres because I’d earned this line. “A criminal.”

She pitched one more sentence over her shoulder: “My husband—”

“Is also under investigation,” the attorney general said, and if smugness were a kitchen appliance, hers would have been a stainless steel Viking range.

Live streams end abruptly when wrists are occupied. Her followers scattered, disoriented by the whiplash of reversing indignation. The bots reoriented to another outrage. Real people called each other. The lake exhaled as if held breath had pushed its water level up by an inch.

The paperwork marched. It was beautiful. If you’ve never watched a fraud case be built properly, you’ve missed a genre of art. Money doesn’t lie. Forms that haven’t been filed don’t spontaneously appear when a judge asks for them. Insurance claims with dates that don’t match storms look like the cheap excuses they are. Shell companies that share addresses with a president’s brother-in-law look like they smell.

At sentencing, the judge—a man whose contempt could steam wood—stacked charges like cordwood. Three years. Restitution. A permanent ban from any position of fiduciary trust in any HOA anywhere. Her husband, Robert, resigned in a press conference that was supposed to look dignified and mostly succeeded at looking wet. Eighteen months for conspiracy and abuse of office. The HOA dissolved like sugar in hot coffee.

We voted to form something that couldn’t hurt anyone if it wanted to. Clearwater Lake Volunteer Association. The bylaws fit on one page. No fines. No power. If a dock rots and falls into the water, we bring a hammer and fix it. If someone wants to plant a tomato, we bring compost. We hold pancake breakfasts and use the money to put lights on the fishing pier and buy the VFW a new microphone.

Pop would have approved. He distrusts meetings. He trusts pancakes.

Part III — The Lake

Peace rebuilds differently than walls do. It grows back like grass where cars used to park. It fills silence in with better sounds. The Hendersons came back. Their grandkids threw themselves off their new dock the way guilt throws itself off cliffs in movies. Mrs. Patterson moved back into her cabin with the green shutters and hosted a block party that ended with four guitars, two harmonicas, and some man I’d never met doing a passable Johnny Cash. The young couple with the baby put up their swing set again, and this time the only person who commented was me, and I said: good.

Property values stabilized because of course they did. You remove fear from a market and it behaves more like a market. We organized tours of off-grid setups. People came from the city to see a septic that works because someone loved it and to touch solar panels that hum quietly like contentment. Kids learned to tie knots on my porch. I carved their initials under the rail like Pop did for me.

We used part of the whistleblower award—yes, there is such a thing, and yes, the defense budget probably funded the new shingles on my roof one way or another—to start Pop’s Legacy Scholarship, because Pop believed in hands that do things and hearts that tell the truth. Five hundred dollars says to a kid going to trade school: we see you. It buys good boots. It buys time. It buys dignity. It buys exactly the thing Pop bought me when I was sixteen and stupid and he handed me a wrench and told me to hold the world still for a second.

The attorney general came back to the lake not for arrests this time but for barbecue. She stood on Pop’s dock and announced the Henley Act—annual independent audits for HOAs, criminal penalties for using citations to manipulate property values, whistleblower protections with teeth. She shook my hand, and it felt like someone closing a circuit.

Netflix so help me God decided to care. HOA Hell: How One Man Took Down a Criminal Empire premieres in spring. They filmed me sitting in Pop’s recliner with the rug slightly off-center because if they’d moved it he would have haunted me. They asked me to walk slowly down my dock and look reflective. I obliged. They asked me to recreate the scene where Delilah kicked the door. I refused. They staged their own door and practiced on that one instead.

Tourists come now, sometimes. They step carefully across Pop’s boards and ask me if I was scared. I tell them I was tired. Fear sticks to your ribs. Fatigue gets into your bones. It was the fatigue that made me angry enough to be brave. They ask me how to fight their own fights. I tell them to get the paper. The paper is where the power lives. The paper is where the lie leaves fingerprints.

Some nights, when my knees behave and the fish act like they remember who I am, I take the boat out. The wiring still holds. Pop taught me to crimp a butt connector properly; it turns out crimefighting uses the same precision. I drop anchor at the cove by Cedar Point and let the engine tick in peace. Above me, the loons do their old song. Around me, water holds the sun. Behind me, my cabin stands with its scar on the door like a medal and the attorney general’s business card taped to the inside of the cabinet where Pop used to keep his cigarettes.

I still get letters. They are wild things. People tell me about HOAs that fined them for their kid’s chalk drawings and for their flag being hung wrong and for their grass growing at the kind of rate grass grows. They tell me about passive circles of chairs at meetings where nobody meets. They tell me about fear in small towns. I write back: gather; document; audit. Then I write: there is a piece of the world you can win. Win that.

Last week, a new couple moved into the lot down by the cove. The woman brought me a pie that tasted like someone’s grandmother and the man walked my perimeter and pretended not to look down at the dock to check the bolt heads. He’s learning. I showed him the filings, the papery spine of the case, the place where the law is a pleasure. I poured him coffee in Pop’s mug and taught him the phrase “Form 1120,” and he looked at me like I’d taught him a swear he could use in church.

Delilah writes sometimes from prison. The first one blamed me. The second one blamed the AG. The third one sounded like a person learning the dial of accountability. I wrote back once. I said: Popularity is not power. Stewardship is. She did not reply. Maybe she will. Maybe when she gets out she’ll move somewhere without boards to chair and find out who she is without a gavel.

Sunsets still do the thing where the world blushes for having been so mean all day and asks the lake to forgive it. The lake always does. I sit with my beer and the day’s reason to be grateful and listen. I think about Pop’s notes in the margins of his Bible, the way he underlined stories where small men killed giants and then took out the trash. I think about paper as armor. About neighbors as weapons if you wield them right. I think about the attorney general sitting in my recliner with her feet cracked just a bit because nothing that works is smooth.

I think about doors. Some of them you open. Some of them you bar. Some of them you let get kicked in because there are men behind the woodshed with badges who want a good angle. And some of them you repair yourself with the grain running just so, stain rubbed in by your palm, nails tapping a rhythm that says: you can knock. We can talk.

There’s a new sign at the end of my driveway where the mailbox used to bear an orange threat. It’s hand-painted, crooked, and Pop would have rolled his eyes and fixed it if he were here. It says:

CLEAR WATER LAKE

Neighbors Welcome

Bullies Beware

Most people smile when they pass. A few honk. The loons don’t care either way. They knew before we did that a place belongs to the ones who listen more than they speak.

And if some day some new version of Delilah arrives with a perfume that lies and a plate that says RULE 1 and a plan sketched on someone else’s map, I have a file. I have a law. I have a community. I have a porch where we can sit. I have a door that’s been mended and shows it. I have a lake.

That’s enough power for the rest of my life.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My grandson whispered of their cruelty. I’m an antique dealer. I made one call: “It’s cleanup time.”

My grandson whispered of their cruelty. I’m an antique dealer. I made one call: “It’s cleanup time.” Part I…

CH2. At My Sister’s Wedding, They Said I Was “Too Poor To Come” — Then the Queen’s Nephew Asked for Me

At My Sister’s Wedding, They Said I Was “Too Poor To Come” — Then the Queen’s Nephew Asked for Me…

CH2. My daughter spent THREE WEEKS organizing her cousin’s party Then found out that she wasn’t invited

My daughter spent THREE WEEKS organizing her cousin’s party. Then found out that she wasn’t invited. Part I —…

CH2. The Father Weeps at His Daughter’s Grave, Unaware That She Is Watching Him

The Father Weeps at His Daughter’s Grave, Unaware That She Is Watching Him Part I The wind sank into…

CH2. Mom Sent A Message: “We Changed All The Locks On The Front Door And Also The Gate…

When my mom texted, “We changed all the locks and the gate code. We no longer trust you,” I knew…

CH2. What Did You Do With It?” I Froze: “$200K? What?” My Sister Turned Pale… 30 Minutes Later….

At the family dinner, my dad leaned toward me and asked, “Tell me, the $200,000 I gave you—what did you…

End of content

No more pages to load