HOA Built on Our Land Without Permission—They Panicked and Ran When We Came Back Armed!

Part I — The Lights on the Ridge

The sun was giving up when we left the highway and took the gravel lane that had always sounded like home—stone on rubber, pine needles flicking the undercarriage. Emily leaned forward and squinted through the windshield. She has a way of leaning into problems before they hit.

“Why are there lights up ahead?” she asked.

There shouldn’t have been. Our ridge was a dark line on any map after sunset. Then the trees parted and something white and wrong rose into the last orange of the day. A rectangle of glass and stucco, all edges and entitlement, with a brand-new ribbon of asphalt gleaming up to the door.

I braked hard enough for dust to pass us.

We got out. The air smelled like hot brakes and that high-country resin you only really know if you’ve spent childhood summers counting tree rings with dirty fingers. A post near the entry held a sign that felt like a dare: PRIVATE HOA—RECREATIONAL OFFICE—RESTRICTED ACCESS.

“Recreational?” Emily said. “On our parcel?”

Survey stakes dotted the duff line. I knew each blaze tree by heart; Grandpa made me memorize them when I was ten and couldn’t see over the hood of the old Ford. The corner pins were exactly where they had been for fifty years. The new concrete wasn’t. It was ten feet over the line and then some. I took photos—stakes, bearings, the sign, the paint on the driveway that boasted a permit number I knew didn’t exist.

A security camera clicked on and whirred as it found me. I raised one palm to it, not in threat, not in surrender—just a record that we saw it and it saw us.

“Cabin,” I said. The one my grandfather milled the beams for and my father shingled with his brothers and I learned to swing a hammer under.

The front door had a shiny brand-new padlock on it. Construction ribbon tangled around sage and an orange portable toilet sat like an exclamation point ten feet off the porch.

Emily went white at the edges. She doesn’t raise her voice when she’s angry. She lowers it. “They locked our front door.”

Back at the truck, I called the county records office and worked my way from a switchboard to a clerk to a supervisor to a man who finally listened. He asked for our parcel number, the development name, and the supposed easement code the sign bragged about. I read off the numbers. He typed. A beat.

“That easement is… odd,” he said, diplomatic as bureaucracy is allowed to be. “The instrument number routes to a subdivision map, not a right-of-way. And the notary registration is flagged.”

“So, it’s fake.”

“I’m saying,” he said, careful, “bring your original deed down as soon as you can. And anything else you’ve got.”

We drove home under a sky full of stars, the kind only black dirt and a long way from town can buy. We hauled out the fireproof box with stamps and signatures. Grandpa’s linework was steady even when his hands shook—1949 on the first sale, 1962 when they added the west slope, 1974 for the stream corridor he bought to keep the cattle off the banks. I spread them out like a family Bible.

“We don’t walk away,” I said, not loud, and felt something in my own voice I hadn’t heard since the days I argued with myself about staying in a job that took more than it gave. “We don’t let anyone teach us who we are.”

“What now?” Emily asked.

I opened the safe and took out what had always been in there because of rattlesnakes and coyotes and men who mistake solitude for vacancy. I checked chambers with a habit that lives in muscle and law. I set the AR in the case and laid the bolt cutter on top of the paperwork.

“We go back at dawn,” I said. “We record everything. And we don’t start anything we can’t finish.”

She nodded, unsnapped the hard case with the drone, and set two body cams to charge. “We’re our own witness,” she said.

Part II — The Morning We Stood

We rolled out in dark that still held last night’s cold. Emily poured coffee into a dented thermos while the truck heater decided if it was up to the job. I checked what I always check—light, chamber, sling—and reminded myself what it was for: rattlesnakes, coyotes, men who mistake other people’s work for building material.

By six-thirty, weak sunlight shattered on the illegal office’s glass. Three luxury SUVs squatted in the new lot like animals that had wandered from a different ecosystem. Two men on the porch nursed coffees they’d tell other men they’d earned.

Emily launched the drone. I stepped out and let the sling catch the rifle’s weight across my chest. The older man stood, gray wave of hair combed like a habit, country-club fitness quietly failing his posture.

“This is private HOA property,” he called. “You can’t be here.”

“This is Parcel 14-B through 14-E,” I said, pointing at the treeline. “Our corners. Our deed. You built on it.”

He smiled the way men do when charm has always been enough. “We had approval. Easement’s recorded. You’re trespassing.”

Emily held up the county-stamped deed and the plat map with our red pencil lines. “Wrong,” she said. “This easement number routes to a subdivision two miles east. This is forgery. You put your sign in our dirt.”

The man on the right muttered, “They’re armed.” Not panicked, exactly—just the sound of calculations changing.

“Are you threatening me?” the older man asked, louder.

“No,” I said. “I’m saying leave my land. You’ll hear from our lawyer.”

A woman with a clipboard peeked out from inside and slammed the door again. The younger man on the other side of the porch finished his coffee in a rush and pretended to have somewhere else to be.

“You’ll hear from ours,” the older one spit, and that was when the look cracked. The drone’s shadow cut across his face. My sling creaked as the wind shifted. He realized the cameras would write this story with or without him.

They left in a small panic, SUVs fishtailing dust and embarrassment.

We cut the padlock on the cabin and opened our own front door. It smelled like cold wood and mouse ambition, the way it always does when a place has been empty. Grandma’s cross-stitch hung crocked over the fireplace. The coffee can of screws on the workbench was where I’d left it when we winterized. No one had been inside.

“They really thought we wouldn’t come back,” Emily said.

“I think they thought we didn’t exist,” I said, setting the bolt cutter on the porch railing and feeling a small part of the last twelve hours drain out of my shoulders.

We drove straight to the county. The woman at the records counter had the kind of posture that tells you she’s seen more nonsense than you’ve brought. We set the deed and the drone stills and the timestamps on the counter. Emily printed three frames from the video—me pointing at the stakes, the sign with the fake instrument number, the pads of their SUVs leaving rubber.

“That’s a lot,” the clerk said.

“And all of it’s real,” I said. “We’re not the first and we won’t be the last. We’re just the ones who didn’t blink.”

She vanished into the back and came back with a man who had an investigator’s beard and a briefcase that had made it through different kind of fights. He introduced himself as Don Moffett, county land investigator.

We gave him an hour and everything in it—deed, surveys, drone, the phone call from last night. He flipped one page at a time, never twice, and then leaned back and blew out air through his nose.

“Well,” he said, in the voice of a man who eats his frustrations with biscuits and gravy. “I’ll be damned. They tried to snake you.”

“Can you shut them down?” Emily asked.

“We can do better,” he said. “We can unwind it, charge the ones who need charging, and make it clear the show’s over. That easement is already under review. If it’s forged—and it sure smells like it—that’s a felony. And padlocking your door? That’s trespass with a garnish of stupid.”

“They’re Stone Brook Ridge?” he added, checking his phone for a text I knew was already on the way to someone with a badge and a better tie.

I nodded. He smiled without warmth. “They’re about to have a week.”

We drove back up the lane at dusk. A white sedan sat near the illegal office, idling like it might be able to erase itself if it kept moving small. The clipboard woman from the porch sat inside crying into her phone. She rolled her window down when she saw us.

“I didn’t know,” she said. “They told me everything was cleared. I’m just the assistant. I only padlocked the door because they told me it was vacant.”

“You locked my grandmother’s house,” I said, not unkind, not soft. It was a sentence that didn’t need adjectives.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“I believe you,” Emily said. “But sorry doesn’t replace homework.”

We left her with the engine running and took two long breaths inside our own doorway.

Part III — The Day the County Came

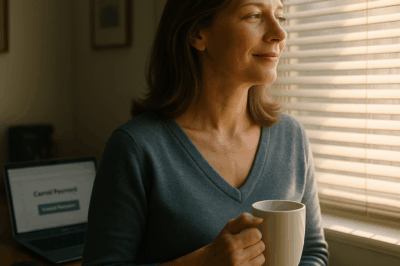

Two days later we sat on the porch. The coffee tasted like strength again. The ridge smelled like itself. Then headlights. Then more.

Three sheriff’s SUVs, decals catching sun. A white county van with steel shelves and boxes of notices. Two news cars with a microwave tower that made the pines look small. Don climbed out of a truck that had dented the way only work does, and the sheriff—McCaffy, built like a fencepost and an old-fashioned oath—walked up.

“Mr. and Mrs. Clay,” he said. “Hope you don’t mind if we do this loud.”

“Be my guest,” I said.

He tipped his chin toward the building that shouldn’t have been there. “We’ve got a court order to shut it down. Zoning board confirmed your complaint. Recorder flagged the instrument. DA saw the forgery. We’ll have two of their board members in custody by lunch if they don’t run.”

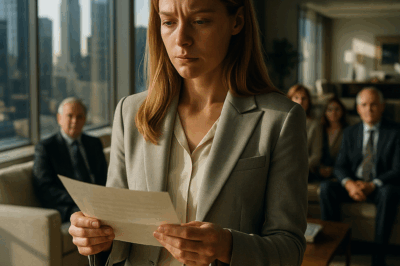

Local news raised microphones like sunflowers. Emily did the talking. She was calm and precise, three parts fact, one part feeling, and left no room for anyone to reassign the story. We were the landowners. The sign was a lie. The deed was real. They padlocked our door. We cut our own lock. The county showed up because the county is supposed to.

Deputies popped their pretty padlocks, put county tape across the doors, and posted a yellow notice in a plastic sleeve that told the story in a font people reflexively obey: STOP—CONDEMNED—UNAUTHORIZED STRUCTURE. The sticker looked good on glass.

Then a gray SUV screamed up late enough to be guilty. The man in the good suit—the one who had said, “You’ll hear from our lawyers”—came out less tall than his posture had promised. He got cuffed without a word, rights read in a rhythm that sounded like music if you’ve ever been on the wrong end of arrogance. The camera got every inch.

The clipboard woman stood to the side holding her badge in two fingers like it was a thing that might bite if she squeezed. She handed it to Don. “I quit,” she said, voice small, and looked smaller in that moment than she had any right to. “I won’t work for people who do this.”

Don looked at the badge, then at her. “You’ll need to help us with the story,” he said—neither absolving nor condemning. “Then you can write your own.”

By late afternoon, the illegal office looked like a stage after someone has ripped the set down. The quiet returned. It’s different when quiet fits.

“Could have ended worse,” I said.

Emily nodded. “We came prepared,” she said. “That’s why it didn’t.”

We raised our mugs to a porched ridge that had decided to be ours again. Preparation tastes like coffee when it’s done right.

Part IV — The Paper Trail and the Pine Line

It took months to put the paper world where it belonged. The recorder voided the fake instrument and hid it behind a red flag future grifters would have to drive past with their eyes open. The DA charged two board members at Stone Brook with forgery and conspiracy to defraud. Their lawyers sent letters that read like threats and boomerangs. The HOA sent a newsletter explaining their vision, then a second explaining the first had been misunderstood, then a third explaining they were “undergoing leadership changes.” The newsletter had always said too much; now it said everything in the space between words.

Insurance want the building gone. That took another order, and the contractor who did the demo refused to be paid by anyone but a check with the county seal on it. It came down in a day, enough concrete and rebar to remind you destruction is also a trade. We watched from the porch and didn’t clap. A hawk rode the warm air above the scrap and did not care about the politics of men.

The assistant—the clipboard woman—came up once more. She had a different haircut and the kind of quiet you get when consequences teach you better than teachers do. She brought a pie because her grandmother told her pies are what you give when you are asking to be seen as more than your worst afternoon. We ate it as if pies have ever solved anything and they never have, but sometimes they make the rest solvable.

Neighbors we’d only ever waved to drove up in trucks with tailgates that squeaked. They brought beer and one brought elk jerky he would have bragged about if he had been that kind of man, which he was not. They apologized for not saying something sooner. Shame and sunlight don’t share a porch. We said what was true: “It’s done. Next time, knock.”

Don came by to tell us the last of the cases had closed. The judge’s signature on paper always looks the same on copies and on lives. “You did the county a favor,” he said. “We can’t do anything until we know. You made us know.”

“You did your job,” I said. “We did ours.”

We fixed fence where their trucks had run over it and re-hung the No Trespassing sign at the switchback because I like the old ways—painted boards and hand letters—better than steel and reflective. I ran new stain along the cabin’s lower wall because winter is a kind of pressure and wood has a memory.

When the first snow came, it erased the last tire track that didn’t belong. The ridge went white. The air got the kind of cold that makes breath visible and men honest. We split wood in a rhythm that doesn’t take thought, and I remembered Grandpa’s hands showing me where not to nick my knuckles on the maul.

In the spring, the county replatted the mess the HOA had made of the lines to the east and mailed us a fresh set of maps with our corners bright. I took Emily to the corner pin down by the dry creek and we found the scribe marks my grandfather had cut with a chisel forty years ago. They were iron in the dirt. Every family should be so lucky to inherit anything that stubborn.

We put game cameras on the ridge line, not because we expected trouble, but because it pleases the heart to catch elk at dusk and coyote at midnight and a mountain lion at two a.m. once that made my pulse lurch in the good way.

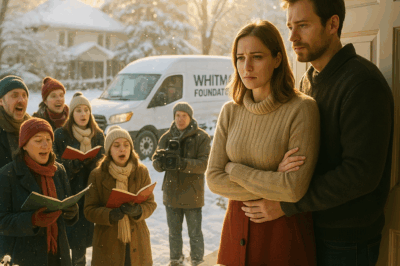

Then there was the morning I heard tires at the base of the lane and walked down to find two men in matching polo shirts and clipboards, the uniform of people who say words like community with a trained mouth. They were new leadership from Stone Brook. They had come to apologize.

They did, in the way apologies from institutions work—too long, too careful, too late. I listened. Emily leaned on the porch rail and watched their shoes. I asked questions that made them use last names. They used them. I said, “If you ever put anything across that line again, it will cost you more than it did the last time, because the second lesson is always more expensive.”

They swallowed and nodded and promised to educate their board. I told them to educate their lawyers first. They left. They won’t come back. If they do, they’ll meet the same coffee and camera and paper they did the first time, which are better weapons than the ones you put in safes.

There’s a temptation in stories like this to make it all high noon and showdowns. Truth lived here: we used fact like fence posts and let the county bring its own hammer. We were armed the way people on land are armed, but we didn’t lift a muzzle. The preparation mattered. The rifle mattered, too. It reminded everyone that we weren’t surprised by what wilderness requires and what men sometimes demand. But what won the day was older—deeds and lines and a county number that would ring if you pushed hard enough.

We still drive the lane at dusk, and the place where the illegal office stood is a rectangle of something trying to turn back into grass. The ridge keeps its counsel. The cabin stays itself.

The HOA will hold another meeting about pet waste and trash cans, and somewhere in their bylaws there will be a line item about “external relations” that is code for what we taught them. I hope they learn it. If they don’t, someone else with a porch like ours will, and the county will drive their trucks up another road, and men will tape another yellow notice to another glass door.

Emily and I sit on the steps with our boots off and dirt across our socks and watch pine tips darken against a cooling sky. She tilts her head against my shoulder, the end of every day I ever wanted in that small weight.

“It could have been worse,” she says again, and it’s not superstition. It’s a promise to not let worse be easy.

“Next time,” I say, and she snorts. “There won’t be a next time.”

There might. That’s what land does to men who think lines are suggestions. But if there is, we’ll do what we did: count the stakes, find the paper, call the people we pay to protect the paper, and meet anyone in our dirt with cameras and coffee and the good kind of patience.

The ridge forgives faster than people do. That’s why we keep it. That, and the way the sun hits the west slope when it forgets to be dramatic and just sinks. That’s ours, the same way the corner pins are. Not because we said it on a porch and meant it, but because our names are in a book in a building in town, and in the timber itself, where Grandpa taught me to cut a mark that would outlast weather and other people’s wishes.

They panicked and ran the morning they saw we had come home and remembered how to stand. The rest was just work.

Part V — Afterword on Boundaries

People ask—neighbors at the feed store, a guy who recognized me at the diner from the news clip, a second cousin who texted once and then twice—what I would have done if the county hadn’t shown up.

The same. Cameras. Paper. Pressure on the places designed to carry it—recorder, zoning, DA. We didn’t win because we had a rifle. We won because we had proof and patience and a county that still answers when you show up with both. The rifle was for snakes. Men, too, sometimes act like snakes. But you don’t shoot them. You make them choose a different rock to sun on.

We built a fence that spring—not because we now feared neighbors, but because it pleases me to see a straight line hold. We hung signs where they help the ignorant and challenge the bold. We repainted the cabin door the color my grandmother swore kept flies away.

The clipboard woman sent a postcard the next fall with a picture of a library on it and a sentence in small careful script: “I start at the county in October. Thank you for not making me into a thing I couldn’t leave.” We kept her card on the map next to the red pencil marks. People change faster than institutions. Both can be asked to.

In the end, there was no cinematic vengeance—no shouting match at noon, no staged humiliation. There was a property line, a law, some paper, two mugs, a drone, a bolt cutter, a rifle that never left its sling, and a couple that decided to remember where they came from. When the storm hit, it did what storms do—ripped the loose boards off. We tightened what we could and let the rest blow away.

If you think this is just about an HOA, you haven’t lived on land someone else wants. This one wore a blazer and a lapel pin. Next time it might wear a friendly smile and an assumption. The answer stays the same: know your corners, keep your records, learn your county’s first names, and be ready to meet anyone on your place with respect and a spine.

We still keep the drone charged. We still keep the coffee tin of screws on the bench. A hawk still rides the thermal above the old office pad every afternoon. He doesn’t belong to us. He belongs to this ridge, and so do we.

Justice didn’t arrive with sirens. It came in a convoy of county trucks and a man with a briefcase older than my patience and a length of yellow tape. It came in a judge’s name and a deed Grandpa signed with ink that barely dried before it was tested. It came in the way Emily’s hand went steady when I reached for the safe.

They built on our land without permission. They panicked and ran when we came back prepared. And then the land did what land always does when people leave it in peace. It went quiet and stayed.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.”

My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.” My Sister Added A Thumbs-Up Emoji. I…

CH2. My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell Apart

My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell…

CH2. My Family Said:”You’ll Firgue It Out” After Moving Away Without Me At 17—When I Made It, They Tried…

At seventeen I was abandoned by my family. I came home to an empty house and found only a note…

CH2. “There’s No Place For You Here!” My Daughter-In-Law Said On Christmas, So I Left. The Next Day…

“There’s No Place For You Here!” My Daughter-In-Law Said On Christmas, So I Left. The Next Day… Part I…

CH2. At Thanksgiving Dinner, My Sister’s Kid Threw His Fork at Me and Said, “Mom Says You’re the Help…

At thanksgiving dinner, my sister’s kid threw his fork at me and said, “Mom says you’re the help.” The table…

CH2. While I Was Lying In The ICU My Brother Said “I Sold Your Apartment In The Center Of Moscow For $65k

When I was fighting for my life in the ICU, my own brother made a shocking confession — he sold…

End of content

No more pages to load