German POWs Thought Canadian Winter Would Kill Them — Until Locals Showed Them How to Survive It

December 1940

The first thing Ernst Bower noticed was the cold.

It hit him the moment the ship’s steel gangway dropped onto the pier at Halifax—a knife-edged wind that slid under his collar and down his spine as if it had been waiting for him personally, all the way across the Atlantic. The harbor was a gray bowl, the sky the same color as the water, the air sharp enough to make his eyes water.

He tightened his wool greatcoat, the same one that had kept him comfortable through winters in Hamburg, and felt—really felt, for the first time—that it was not going to be enough.

“Welcome to the edge of the world,” muttered the U-boat officer beside him in German. “They say the winter here kills more men than bullets.”

Ernst had heard the same rumors. They all had.

Back in Germany, officers had shown them maps and thick cold-weather manuals. Canada, they’d been told, was less a country and more a frozen emptiness: a primitive colonial backwater buried under snow and ice, where winter descended in November and did not loosen its grip until May. Stories passed through the barracks like ghost tales. Men caught in sudden storms, frozen standing upright. Nose, ears, fingers gone in minutes.

“Exposed skin freezes solid,” one lieutenant had promised them with morbid relish. “You step outside unprepared, you become a statue.”

So when the guards shouted for them to move down the gangway, Ernst thought: This is where we die. Not from depth charges in the Atlantic, not in a blaze of heroic fire, but years later, forgotten, sealed in ice on a continent we had never seen.

He stepped onto Canadian soil expecting it to be the first step toward his own slow execution.

Instead, a guard at the bottom of the gangway—broad-shouldered, with a patch of frost clinging to his mustache—gave him a bored, almost friendly nod.

“Keep it moving, fellas,” the guard said in accented English, then repeated in slow, careful German, “Lasst uns vorangehen, Männer. Move along. You’ll warm up on the train.”

Warm up.

The words sounded like a joke.

They were herded from the docks to waiting rail cars—old wooden coaches, yes, but not cattle trucks. Inside, it was already warmer than the dockside wind, a faint hiss of steam coming from somewhere beneath the floorboards. As the train lurched away from the harbor, Ernst found a seat by the window and pressed his gloved hand against the glass.

Germany, he thought, was behind him.

Death, somewhere out there in the snow ahead.

He expected endless white emptiness.

Instead, kilometer after kilometer, he saw something else.

Forests that seemed to go on forever, black trees stitched with snow. Then fields—vast, flat squares of land larger than the entire neighborhood he’d grown up in, framed by fences and barn roofs dusted white.

At first he assumed it was illusion, a trick of scale. But the hours passed, and the pattern repeated: more forests, more fields, small towns appearing and vanishing in minutes.

The towns surprised him. They were not crude frontier villages. They were…modern.

Electric streetlamps glowed pale in the short winter afternoon. Phone lines ran in neat parallel lines along the tracks. Roads were paved, not muddy ruts, and almost every house seemed to have an automobile parked in front of it. Even from the train window he could see glass in every window, roofs solid and straight.

One of the younger prisoners behind him—Klaus Hermann, a former Hitler Youth leader with sharp eyes and a jaw that always seemed clenched—leaned forward.

“This is supposed to be the wilderness?” Klaus scoffed. “They look more comfortable than half of Germany.”

“Propaganda,” another man muttered. “We were told they lived like peasants.”

Ernst said nothing. He watched a farmer drive a tractor across a field of snow, the machine dragging some complicated contraption behind it, cutting furrows in the frozen soil. A tractor, in this cold. Back home, his uncle’s village had one tractor for everyone within walking distance. Here, a single farmer owned one and worked a field the size of four German villages.

Canada, he realized, was not the frozen, backward outpost he’d been promised.

That should have comforted him. Instead, it made the cold feel even more ominous. These people had learned to live in it. They’d had time and wealth enough to bend this brutal climate to their will.

And we, he thought, are arriving here as prisoners.

What chance do we have?

The camps were scattered across half a continent: places with names that sat awkwardly on German tongues—Bowmanville, Medicine Hat, Lethbridge. Ernst’s camp was one of the prairie ones, built on flat land that seemed to stretch forever in every direction.

At first glance, the camp looked flimsy.

The barracks were simple wooden buildings, tar-paper roofs dark against the snow. Barbed-wire fences turned the perimeter into a crude, bristling line. Guard towers rose at the corners, manned by soldiers in thick coats and fur-lined hats, rifles slung casually over their shoulders.

Ernst eyed the buildings in disbelief.

“This can’t be it,” he whispered. “These walls…they’re just boards.”

He imagined the first real storm—those legendary Canadian blizzards that swallowed men—and saw the barracks peeled open like tin. The wind would knife through the cracks. The flimsy roofs would rip off. They’d all die in a single night, frozen under thin blankets in bunks that might as well be coffins.

That first week, the temperature dropped day by day like steps on a staircase.

Minus ten. Minus twenty. Minus thirty.

Nights came early and hard, black skies blazing with cold stars. The guards outside moved through it like they’d been born in it, their breath pluming in the yellow cones of the searchlights, boots crunching on snow loud enough to be heard inside.

Inside the barracks, the prisoners clung to one another’s warmth.

They dragged bunks closer together, wore their German wool coats even in bed, pulled every blanket tight around them. Some cut strips off their greatcoats and tied them around boots, desperate to keep heat from leaking out through their feet.

An older sailor, who’d served through winters in the North Sea, tried to sound confident.

“It’s like home,” he insisted one night, teeth chattering audibly. “Just…a bit colder.”

The wind howled in response, rattling the barracks walls. Snow hissed against the windows like sand.

When the lights went out, fear bloomed in the dark.

Ernst lay awake listening to the building creak and sigh, the icy gusts prying at the seams. His mind insisted he was already feeling his blood slow, his fingers stiffen. He pictured orderlies in the morning, moving from bunk to bunk, shaking blue shoulders that would not respond.

This is it, he thought. We’re already dead. The cold just hasn’t finished the paperwork.

The officers, huddled in their own barracks, were no calmer. They held urgent meetings, whispering around rough wooden tables by the light of a single bulb. They talked of rationing physical movement to preserve body heat, of assigning the younger men to stand night watches with candles to make sure no one simply stopped breathing in his sleep.

“We must be ready to report these conditions,” one insisted. “If any of us survive long enough.”

Some of the prisoners wrote letters home that night, careful, trembling words on thin paper: if this is the last letter you receive from me…

The censors would read them, slice out certain phrases, maybe never mail them at all. Still, men wrote, because it was the only weapon they had: ink and paper against a winter that seemed intent on erasing them.

Outside, the thermometer nailed to the side of the guardhouse dropped another notch. Minus forty with the wind.

Colder than anything Ernst had ever imagined.

He closed his eyes and waited to be turned into a statistic.

Morning came.

He woke up alive.

So did everyone else.

Death did not arrive in a single night.

It hung over them instead, a patient, invisible enemy. The men began to measure their days in degrees and rumors. If it grew any colder, if a real blizzard hit, if the wind changed…

And then the Canadians did something no one had predicted.

They started arriving at the barracks with boxes.

One morning, the door banged open and a gust of air knifed inside, trailing snowflakes and two guards hauling a wooden crate between them. Another followed with cardboard boxes stacked in his arms, labels scrawled in looping, unfamiliar handwriting.

“All right, boys,” one guard called in rough German. “On your feet. Clothing issue.”

Ernst exchanged a wary glance with Klaus.

“Clothing?” Klaus murmured. “What, burial shrouds?”

But the guards pried open the crate, and what spilled out was not shrouds.

Wool.

Real, thick wool—socks, three pairs per man, the fabric heavy and scratchy in that comforting way that promised warmth. Mittens lined with fur that climbed past the wrist. Knitted scarves, each one uniquely patterned—snowflakes, stripes, diamonds—clearly handmade.

The big surprise was the coats.

They called them “mackinaws”—short, heavy jackets, double-breasted, lined with wool, made to be armor against exactly this kind of cold. The guards tossed them to the prisoners, laughing as some of the Germans nearly staggered under the weight.

“And these,” said one older guard, a man with a weather-beaten face and eyes that crinkled easily, holding up a knitted cap. “We call them toques. Pull ‘em down over your ears, you’ll keep your ears.”

He placed the hat directly on Ernst’s head, tugging it down playfully until it covered his eyebrows. The gesture was so casual, so intimate, that Ernst flinched reflexively.

“Easy,” the guard said, then in German, his accent thick but understandable: “If your ears freeze, they break off. We’d rather not be picking them up.”

Laughter rippled through the barracks, half nervous, half disbelieving.

They expected the guards to dump the clothing and leave. Instead, the Canadians stayed.

That same day, a farmer’s truck arrived at the gate, engine coughing in the cold. Out climbed a woman bundled in a long coat, cheeks red from the wind, and a teenage girl by her side. They carried baskets of more knitted things—socks, scarves, mittens that still smelled faintly of wood smoke and whatever soap Canadians used on their laundry.

The woman moved down the rows of bunks like she was visiting neighbors, not enemy soldiers. She spoke almost no German, but warmth needs little translation. She tapped men on the shoulder, re-wrapped their scarves, tucked loose ends inside coats, adjusted hats until ears were fully covered.

At one bunk she shook her head, clucking her tongue, and hauled the startled prisoner to his feet.

“No, no,” she said, pointing at his boots. “Snow—inside. Bad.”

By pantomime and a scatter of English words, she showed them how to stamp the snow off their boots before coming inside so it wouldn’t melt and soak their socks. Her daughter demonstrated how to pull their new wool socks up over the bottom of their trousers, sealing the gap where snow might sneak in.

These were small things. Trifles. The kind of knowledge you barely realize you have when you grow up with winter as a yearly companion. But to the Germans, it felt like being handed a secret code.

The guards took over where the woman left off.

“Layers,” one explained, gesturing at his own clothing: shirt, sweater, mackinaw. “Many thin. Not one big. Air between—” he puffed his cheeks and made a motion of insulation “—keeps you warm.”

Another patted his chest.

“Move,” he added, jogging in place a step or two. “You must walk, work, keep blood moving. But not too much. If you sweat—” he wiped his brow, then shivered dramatically— “wet clothes, you freeze.”

They drilled it into them: fingers, toes, ears, nose—guard those first. Never touch metal with bare skin. If you see white patches on someone’s face, shout. Frostbite doesn’t hurt, not at first.

Ernst listened, absorbing every word. He felt a complicated knot tightening in his chest.

These men are my enemies, he thought. Yet they are teaching me how not to die.

He remembered lectures back home about inferior nations, about rugged German toughness, about how non-Germanic peoples were too soft to endure real hardship.

But it was not German officers standing in this barracks, demonstrating how to bank snow around a building to keep the wind from crawling under the floor. It was a Canadian sergeant from a town whose name Ernst had forgotten, sharing tricks his grandfather had taught him.

Real strength, Ernst thought uneasily, might look different than he’d been told.

The food broke their certainty next.

The first morning Ernst lined up in the mess hall, he braced himself for disaster. Thin soup. A crust of stale bread. Black, bitter liquid pretending to be coffee. That was what they’d heard about prisoner-of-war camps.

Instead, he stepped to the front of the line and stared.

His tray filled with hot porridge, thick and steaming, a scattering of brown sugar turning to syrup where it touched. Beside it, four strips of bacon, crisp edges still popping faintly. A heel of fresh bread, so soft the steam rose when the server sliced it, a pat of yellow butter softening on top.

“Milk?” the Canadian behind the counter asked.

Ernst blinked. “Milk?”

“For your coffee,” the man clarified, lifting a pot.

Real coffee. Real milk.

The smell alone was almost enough to make Ernst’s knees buck.

He carried his tray to a table as if afraid someone would snatch it away, sat, and took a bite. The porridge was simple but hot, the sugar a luxury he hadn’t tasted in years. The bacon…for a second, he was back at his parents’ table on a Sunday morning before the war. Before ration cards and propaganda posters and air-raid sirens.

Across from him, the U-boat officer who’d joked about statues stared at his own tray, eyes wide.

“This…this is more than my family has at home,” the officer whispered. “In Berlin, officers are eating turnips and substitute coffee. And here we are, prisoners, eating like this.”

Later, Ernst would do the math in his head, then more carefully in his diary: two thousand eight hundred calories a day, sometimes more. Meat at lunch and dinner. Fresh vegetables pulled from root cellars. Bread so fresh it seemed impossible in a world at war.

Every meal felt like an indictment of everything he’d believed about German power.

If we are the master race, he thought, why can they feed us better than we can feed our own officers?

The camp itself deepened that unsettling impression.

The barracks, for all their simple wooden walls, had a secret: heat. Real heat. Furnaces in the basements fed hot water through pipes in the walls, radiators ticking gently on the coldest nights. Thermostats—small, unremarkable devices—held the interior steady around eighteen degrees Celsius, no matter what was happening outside.

Turn a handle in the washroom and hot water poured from a tap as if winter didn’t exist. Electric lights flicked on without hesitation—no dimming, no ration-induced blackouts, no sudden sleeps of darkness as they’d known in German cities.

One afternoon, in the middle of a howling storm, Ernst watched a refrigerated truck rumble up to the gate at Medicine Hat, where he’d been transferred. A refrigerated truck. In January.

Milk, someone explained. It had to be kept from freezing solid.

Germany was scraping together enough trucks to keep the army supplied. Canada was using specialized vehicles to make sure prisoners got fresh milk without ice crystals.

The war propaganda he’d memorized in training began to crumble under the weight of these details. The world described to him—weak democracies, decadent, industrially soft—did not match the world he could touch with his own hands.

Maybe, he thought, we’ve been lied to about more than the weather.

They were still prisoners.

The barbed wire was real. So were the guard towers and the rifles. Men who approached the fence with the wrong intentions were warned off sharply. Those who tested the limits learned that Canadians could be deadly serious when it came to security.

But within that perimeter, something unexpected blossomed.

Work details took small groups of prisoners to surrounding farms. They rode in the backs of trucks, breath fogging, wooden shovel handles bumping their knees. In the fields, they pulled sugar beets from frozen soil, the work exhausting, their backs knotting, their hands numbing even through mittens.

And yet the farmers paid them.

Twenty-five cents a day—not in Canadian currency but in camp scrip they could spend at the canteen on cigarettes, chocolate, small luxuries.

In European camps, they’d heard, work meant exploitation. Here, the farmers insisted on fair trade, even for enemy labor. It would have been easy to tell themselves this was simple self-interest, a way to get work done.

But that explanation grew shaky on the day of the blizzard.

It was February 1943, the plains laid bare under a low, iron sky. The wind had been rising all day. By evening it was a living thing, screaming across the prairie, hurling snow like handfuls of nails.

The storm arrived not as a gentle drift but as a wall—white, stinging, blinding.

From his barracks window, Klaus squinted into the swirling chaos and could barely see the nearest tower. The guard on duty had drawn his scarf up over his mouth; snow had already crusted his eyebrows, his lashes.

The kitchen was on the far side of the camp. The path between barracks and galley vanished under drifts in minutes, the wind carving shapes in the snow as if trying to erase the very idea of a road.

Breakfast, the men muttered, would be delayed. Lunch, too. No one expected anyone to risk their lives just to feed prisoners.

They were wrong.

The first truck’s engine announced itself before anyone could see it—a low, straining growl fighting against howling wind. Headlights emerged from the blizzard as two weak yellow orbs, skewed sideways as the driver wrestled with the drifts. Behind it came another, and another.

Not military trucks. Farm trucks.

When they finally ground to a halt inside the camp, the doors flung open and civilians climbed out: men in patched coats and fur caps, women bundled in blankets, their faces red and raw from the storm.

They moved like ghosts in the blowing snow, each bearing something heavy—enormous pots wrapped in blankets to keep the contents hot, sacks that clinked with the weight of bread loaves.

Klaus watched, stunned, as one middle-aged man nearly lost his footing, his boot sliding on ice. He caught himself on the truck’s fender and laughed—a brief, white plume in the freezing air—then took up his burden again and trudged toward the mess hall.

They have no reason, Klaus thought. No reason at all.

The prisoners could offer them nothing. They were the enemy. Any Canadian could have stayed home by a warm stove, confident that missing a few meals would not kill well-fed men.

Yet here they were, leaning into a wind that tried to tear them off their feet, faces stung raw, risking frostbite and worse for men in gray uniforms behind barbed wire.

That night, after he’d wrapped his hands around a tin mug of hot soup that tasted like life itself, Klaus sat on his bunk and stared at the wooden planks above him.

He thought of the endless speeches he’d heard as a boy: about strength, about ruthlessness, about how the truly superior did not waste their compassion on the weak.

We believed we were strong because we were hard, he realized. Because we knew how to crush.

But the farmers in those trucks had displayed a different kind of strength—one that did not fit into the Nazi worldview at all.

Real strength, Klaus wrote carefully in his journal that night, is not proven by how much suffering you can inflict. It is proven by how much risk you will take to keep others from suffering—even when those others are your enemies.

The words felt like treason. They also felt, for the first time in his life, completely true.

War, even at a distance, continued to grind on. News filtered through camp rumor, Red Cross bulletins, snatches from guards’ newspapers. Cities bombed into rubble. Fronts collapsing, then shifting, then collapsing again.

The prisoners were stuck in a strange limbo: powerless, yet safer than their own families under the bombs. That knowledge gnawed at them, especially at Christmas.

In December 1941, Ernst woke expecting nothing more than another day of captivity with a thin veneer of holiday ache. Instead, he stepped into the dining hall and stopped dead.

The smell hit him first: roast meat, bread, spices. The long tables had been pushed closer together, covered with what looked like real tablecloths. The kitchen staff moved back and forth with heavy trays that shimmered with heat.

Turkey.

Golden-brown, glistening with juices, stuffed so plump the skin looked ready to split. Bowls of mashed potatoes, butter melting in bright yellow pools on top. Gravy in metal pitchers. Cranberry sauce that looked like jewels.

For a moment, the room was utterly silent. Then a murmur rolled through the prisoners like wind through tall grass. Some laughed, brittle and disbelieving. Others simply stared, eyes suddenly wet.

“We are the enemy,” one man whispered. “What is this?”

It wasn’t just the food.

Packages had arrived from Canadian families, addressed simply “To the prisoners.” Inside, Ernst found socks knit with careful patterns, homemade cookies wrapped in wax paper, tobacco tins, decks of cards, slim books with English words on the cover and small handwritten notes tucked inside.

A letter lay on the top of one box, written in careful block letters by a child.

Dear soldiers, it read. We hope you are warm and safe. Merry Christmas.

Ernst had not cried since he was a boy. The tears surprised him now, stinging his eyes as he folded the letter back into its envelope and tucked it inside his pocket as if it were something fragile that might break.

That night, after the feast, the camp chaplain—a Canadian—quietly handed over a stack of hymnbooks in German, mailed from a church in town who had combed their basement for old copies.

“We thought you might want to sing the songs you know,” the chaplain said.

The prisoners gathered in the barracks, candles stuck into empty tin cans, the flickering light throwing gentle shadows on the wooden walls. Someone opened a hymnbook and began “Stille Nacht” in a trembling baritone. Others joined, voices steadier as the verse went on.

The words about peace and calm and holy nights echoed strangely in a camp built for war’s debris. Still, for a few minutes, with snow pressing softly against the windows and the glow of candles warming their faces, the prisoners could almost believe in the world those hymns described.

Later, Ernst sat at the edge of his bunk with a pencil in hand and a sheet of paper spread over his knee. He wrote to his mother, aware that the camp censor would read every line.

We are prisoners, he wrote, and yet we are treated like guests who have fallen on hard times. Today, the local church sent us hymnbooks in German. A farmer’s wife brought us Christmas bread like we used to have at home. I have not felt this kind of human warmth since before the war.

He hesitated, then added a final line that felt dangerous even as it forced its way onto the page:

I do not know what we have become in Germany that we have forgotten this is how civilized people behave.

When the censor read that letter, he paused. It contained no secrets, no escape plans, no troop movements. It was dangerous in a different way—because it hinted at ideas that could pull the foundations out from under an entire worldview.

The letter went into a folder with others like it, forming a quiet record of transformation.

The rest of the transformation was more deliberate.

Boredom is a powerful enemy in a camp, and the Canadian commanders knew it. Idle men grow restless. Restless men, even well-fed and warm, look for trouble.

So they built a different kind of weapon against unrest: classrooms.

Prisoners who had been professors, teachers, engineers before the war organized courses. The Canadian government sent textbooks—hundreds and eventually thousands. Mathematics. Engineering. History. Philosophy. Languages.

Camp 30 in Ontario came to look, at certain hours, less like a prison and more like a college campus behind wire. Men bent over notebooks, arguing about the themes of novels that had been banned in the Reich. They took correspondence exams through Canadian universities and received real credits.

“You could finish your degree before the war is over,” one guard joked to a prisoner in the hallway.

The prisoner shrugged, then smiled faintly. “If there is a Germany to return to.”

In those classrooms, the men rebuilt parts of themselves that the war had stripped away. They remembered that they had been more than uniforms and serial numbers. There were minds here, not just muscles.

And the lessons overlapped with what the winter itself was already teaching them.

Survival here was not a solitary act of will. A single man, dumped in the middle of the prairie without knowledge or help, would be dead within hours. The only reason any of them were alive to attend classes, to eat turkey, to sing hymns, was that an entire society had put its knowledge in their hands.

A guard showing a prisoner how to line the inside of his boots with newspaper for extra insulation; a farmer explaining crop rotation; a local mechanic demonstrating how to thaw a frozen engine block without cracking it—these were every bit as educational as the lectures on engineering and literature.

Canada had mastered winter through cooperation, not brute force. The prisoners could see that now. Knowledge passed down generations, shared freely even with enemies, had turned the killing cold into merely another challenge to be managed.

We thought strength meant marching in lockstep, Ernst wrote once. Maybe it means something closer to this: everyone bringing what they know, so that no one dies if it can be prevented.

The war ended on paper in 1945.

For the men behind the wire, it ended more slowly, in rumors that solidified into facts, in flags lowered and raised, in the sudden easing of guards’ shoulders. News of Hitler’s death arrived. The Reich surrendered.

But the world they’d left behind did not simply rewind.

In May 1946, a year after Germany’s unconditional surrender, the ships began running in the other direction.

Ernst stood on the deck of a transport vessel, the cold Atlantic wind familiar now rather than terrifying. In his duffel bag lay everything he owned: the Canadian wool coat that had been his armor for five winters; two pairs of thick socks knitted by a woman whose name he did not know; a small wooden cross carved by another prisoner; and a book on modern agriculture gifted to him by a Canadian officer who had said, “You’ll need this when you go home.”

Home.

The Red Cross letters told the story in clinical lines. Hamburg: seventy percent destroyed. Family house: gone. Father: killed in the raids of ’43. Mother: dead in Dresden. Younger brother: missing on the Eastern Front, presumed killed.

The ship slid into the harbor where he had once worked on the docks as a boy. Now the city that had raised him looked like the ruins of some ancient war, not the aftermath of the one he’d just survived.

Streets were choked with rubble. Walls stood alone, windowless and blackened. People moved through the devastation wrapped in what scraps they’d salvaged—coats too thin, shoes too worn, eyes too old. Children picked through garbage heaps with methodical desperation.

The smell was a mix of ashes, sewage, and something sickly sweet he tried not to identify.

They gave him ration cards at a center crowded with hollow-cheeked faces. Two thousand calories a day, the officials promised—on paper. In reality, the food deliveries faltered. Shelves went bare. Soup stretched farther every week.

When winter came, it hit like a hammer.

Coal was scarce; wood, scarcer. People burned broken furniture, then doors, then books, anything that would catch flame. Windowpanes had long since shattered in the bombing; cardboard and planks covered the gaps, but cardboard does not stop the cold.

Ernst found himself in a half-ruined apartment block, sharing space with families who’d lost everything. They huddled together in one room, wearing everything they owned. Heavy coats over shirts over vests. They wrapped themselves in blankets and still shivered so badly their teeth rattled.

“This is how we freeze,” one old woman said dully. “At least it will be quiet.”

Ernst listened to the wind whistle through cracks in the walls. It was quieter than the Canadian winters he’d known, but more deadly. There were no furnaces humming in the basement. No guards bringing boxes of coats. No farmers arriving in trucks full of soup.

Just hunger and cold and the worn-out stubbornness of people with nowhere else to go.

He looked around at the coats worn tight over thin bodies.

“Take them off,” he said suddenly.

The others stared at him as if he’d gone mad.

“Are you insane?” a man demanded. “It’s below zero!”

“Not off completely,” Ernst clarified. “Listen. In Canada, they taught us—”

He grabbed his own coat and shrugged it off, exposed briefly to the icy air in his shirtsleeves. He felt the cold bite but ignored it, moving quickly.

“You wear many layers,” he said, holding up the coat, then his sweater, then his shirt. “Thin ones. With air between. The air warms and stays. If you wear everything in one heavy layer, it does not work as well.”

Skepticism warred with desperation. In the end, desperation won. They let him rearrange their clothing, found spare shirts and scarves, wrapped them differently. He showed them how to stuff newspapers inside their shoes, how to tuck pant legs properly into socks, how to build makeshift insulation out of anything that trapped air and stayed dry.

They were not suddenly comfortable. But for the first time in days, their shivering slowed. Fingers and toes, previously numb, tingled with returning warmth.

He taught them how to bank snow against the building’s base, piling it high so the wind would skim over instead of under, just as a Canadian guard had shown him years before. He explained frostbite, what to look for in children’s faces—white patches that meant danger, not health.

The Canadian coat he’d brought home went around the frail shoulders of the old woman who’d resigned herself to freezing. It nearly swallowed her, but the wool trapped her remaining body heat.

Without those foreign tricks, Ernst knew, many of the people in that building would not see spring. Even with them, the winter of 1946–47 earned a name: the hunger winter. People died in doorways, in beds, on streets. Frost turned bodies stiff before friends and family could move them.

Ernst survived, but the survival felt bitter.

“I outlived the war,” he murmured once, watching a cart piled with corpses rumble by, “because my enemies taught me how.”

Klaus’s homecoming was worse.

His city was gone. His parents, gone. Every person he would have rushed to hug at the station, or knocked on the door of, or shared a drink with in a half-ruined tavern—they were dead or scattered.

He drifted through ruins for two years, trying to assemble some kind of life from the wreckage. He took odd jobs, slept in basements, stared at walls and saw not the future but those Canadian trucks emerging from the blizzard, farmers fighting the wind to carry soup to men like him.

Germany felt like a stranger—one that refused to admit what it had done, what it had believed, and how catastrophically wrong it had been.

So when he saw the notice about Canada’s new immigration program, he didn’t hesitate.

Former prisoners of war, the announcement said, with clean records—no SS, no war crimes—could apply for immigration if they possessed skills Canada needed. Farm labor. Mechanics. Teachers. Engineers.

Come back, the subtext read, not as prisoners this time but as settlers. Start again.

Klaus put his name down. So did Ernst. So did thousands of others who had learned, behind wire and under snow, that there was another way to live.

Friends heard of their plans and reacted with disbelief.

“You want to go back to your prison?” one man asked, appalled. “To the people who beat us?”

“They didn’t beat us,” Klaus replied quietly. “They defeated us. That is not the same thing.”

He thought of the blizzard, of the soup, of the knitted socks, of the guard tugging a toque down over a German’s ears so they wouldn’t freeze and break off.

“I saw what real strength looks like,” he said. “And I would rather build my life among people who understand that strength and kindness are not opposites.”

Canada, when they stepped onto its soil the second time, looked different.

The wire was gone from the camps, or going. Some barracks had been torn down; others were being repurposed as storage or housing. In Bowmanville and Lethbridge and Medicine Hat, the empty lots where the compounds had been were being folded back into the towns like healed scars.

But the air smelled the same—clean and cold and faintly metallic in winter, sweet with earth and grain in summer.

Horst Liebeck, the former U-boat engineer who had once stood on the Halifax dock convinced this place would kill him, now returned to the same harbor as a civilian applicant, papers in hand.

Within a few years he was working as a marine engineer, using what he’d learned about the sea and machinery to design safety systems for Canadian fishing vessels. Men whose fathers had hunted his submarine now sailed on boats he helped make safer.

Ernst bought a farm in Saskatchewan.

The land seemed to go on forever in every direction, sky a dome so huge it made him dizzy. He planted wheat and barley and sugar beets, applying every lesson he’d learned from Canadian farmers and that slim agricultural textbook. He bought his own tractor, then another, machines that would once have seemed impossibly extravagant but here were simply tools of the trade.

On winter mornings, he sent his children outside wrapped in sweaters, shirts, and mackinaws, wool socks pulled over pant legs, scarves tucked properly into coats, toques pulled down snug. He taught them to skate on the frozen pond behind the house, the blades of their skates scratching paths over the ice.

“Never leave someone outside alone in a storm,” he told them. “In this country, everyone looks out for everyone else. That is how we live here.”

When the wind began to rise and snow thickened, he checked on neighbors. If a storm was bad enough, he’d load a truck with food and blankets and drive through the whiteout to a house he knew was vulnerable—an old widow, a young couple with a newborn—thinking always of those farmers in 1943, leaning into the blizzard with pots of soup.

Klaus ended up in Lethbridge, teaching at a high school built not far from where his POW camp had stood.

The first time he walked past the place where the wire had once cut the sky into jagged lines, he stopped and closed his eyes. He could still hear the clink of boots on frozen gravel, smell the coal smoke from the furnaces, recall the bite of the wind.

Now students biked past that spot on their way to class, scarves trailing, laughter echoing on winter air. They had no idea what had once stood there.

In his classroom, Klaus taught history and citizenship.

He spoke to his students about treaties and constitutions, elections and responsibilities. Eventually, as they grew older and the curriculum allowed, he spoke about the war.

Not at first about Canada’s battles. Not about Dieppe or Juno Beach or the long convoys crossing the Atlantic. Instead, he told them about a February blizzard at a prisoner-of-war camp, and the trucks that came anyway.

“Your country defeated us,” he told them one day, leaning against his desk, hands folded loosely, “not just with tanks and ships and planes. Those mattered, yes. But what broke us—what broke me—was discovering there was a better way to be human than anything I had been taught.”

He saw their eyes on him: some curious, some skeptical, some confused. They had grown up with stories of their grandfathers as heroes, not with the idea that heroism could look like delivering soup to the enemy.

“We believed strength meant never showing mercy,” he said. “We believed being hard and cruel proved we were superior. But when the cold came for us, it was your farmers, your guards, your mothers and grandmothers who drove into the storm. They shared what they knew. They refused to let us die when they could have looked away.”

He let the silence sit, the hum of the radiator the only sound.

“Real strength,” he continued, “isn’t measured by how many people you can crush. It’s measured by how many you can carry through the winter.”

He pointed toward the window, where snow was beginning to fall in lazy, gentle flakes.

“This country is hard,” he said. “The winters don’t care who you are. German, Canadian, rich, poor. The cold will kill you all the same if you face it alone. The only reason any of us survive here is because someone else teaches us how.”

That, he told them, was what civilization really meant: not marble statues and grand slogans, but hot soup carried through driving snow, mittens knitted for men whose names you’d never know, the simple decision to share knowledge that keeps someone else alive.

By 1953, thousands of former German prisoners had returned to Canada as immigrants. They brought wives from bombed-out cities, children born in refugee camps, memories that woke them sweating at night. They arrived with accents and scars and hands that knew both how to salute and how to dig beets from frozen fields.

They settled wherever Canada would have them: farms in the prairies, machine shops in Ontario, engineering offices in Halifax, classrooms in Alberta.

In coffee shops and around kitchen tables, they told their own children pieces of the story.

Not always the whole thing. Not always the part about believing in racial superiority or cheering for victories that now felt like preludes to disaster. But they all, in one form or another, repeated the same lesson:

The winter had not killed them because Canadians had refused to let it.

Not out of weakness. Not because they were soft.

Because they were strong enough to be generous.

Ernst’s eldest son once asked him, on a night when the wind was rattling the farmhouse windows and snow was piling high against the door, “Papa, why did you come here? You could have stayed in Germany.”

Ernst thought of the ruins of Hamburg, the hunger winter, the old woman wrapped in his Canadian coat. He thought of hot porridge in a prison mess hall, of a farmer’s wife tucking a scarf inside his borrowed mackinaw, of hymnbooks in German sent by strangers.

“Because here,” he said slowly, “I learned what it means to survive in a way that lets you live with yourself afterward.”

Outside, the storm howled. Inside, the furnace hummed, and the house was warm.

Across the country, in a small classroom in Lethbridge, a teacher with a German accent was telling a roomful of Canadian teenagers that the true test of a nation wasn’t how it treated its friends, but how it treated the people it called enemies when those enemies were helpless.

On the coast, a marine engineer watched a fishing boat he’d helped design head out into rough North Atlantic swells, its safety systems tested against the same unforgiving sea that had once hunted him.

The war was over. The camps were gone. But the lesson remained, carried in stories and family traditions, in the way a parent wrapped a scarf around a child’s neck or a neighbor checked another neighbor’s lights when the temperature dropped.

The German prisoners had arrived in Canada certain that the winter would kill them.

Instead, it taught them something far more dangerous to the world they’d left behind:

That survival is not the highest goal.

How you survive—and who you help to survive with you—matters more than any banner, any border, any anthem.

They carried that lesson with them all their lives, passing it from one generation to the next, until it was no longer about Germans and Canadians at all, but about humans in hard places, choosing—again and again—to be strong in the only way that really changes anything.

By refusing to let the cold have the final say.

News

CH2. Why the Germans Feared the “Maple Leaf Regiment” More Than Any Other Allied Unit

Why the Germans Feared the “Maple Leaf Regiment” More Than Any Other Allied Unit December 1943, Ortona, Italy. The room…

CH2. German U-Boat Survivors Clung to Wreckage 19 Hours — Then an American Captain Disobeyed Orders

German U-Boat Survivors Clung to Wreckage 19 Hours — Then an American Captain Disobeyed Orders May 6, 1943. Mid-Atlantic. 3:47…

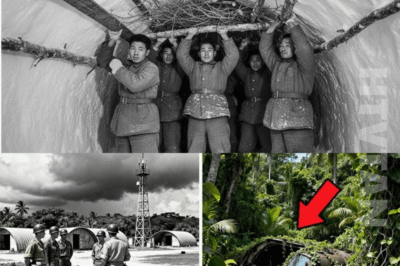

CH2. Snow Tunnels of Siberia: The Secret POW Shelters That Saved Thousands

Snow Tunnels of Siberia: The Secret POW Shelters That Saved Thousands The train didn’t stop so much as shudder to…

CH2. The Secret Sherman: Why German Troops Couldn’t Destroy US M4 Tanks

The Secret Sherman: Why German Troops Couldn’t Destroy US M4 Tanks July 27th, 1944, the fields near Saint-Lô were a…

CH2. What Eisenhower Said When Patton Saved the 101st Airborne

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Saved the 101st Airborne If Patton didn’t move in time, the 101st Airborne Division was…

CH2. Why Germans Feared This Canadian General More Than Any American Commander

December 26, 1944. Four words changed everything: “We’re through to Bastogne.” General Patton had just accomplished the impossible—pivoting an entire…

End of content

No more pages to load