German Commander’s Last 90 Seconds – The Weapon That Destroyed 47 U-Boats

The sea looked wrong.

Kapitanleutnant Bernhard Müller had learned to trust that feeling long before the war stopped being about glory and started being about survival.

He stood in the conning tower of U-672, steel under his boots shivering very slightly with the pulse of the diesel engines. Above him stretched the gray dome of a North Atlantic sky, low and heavy, smeared with cloud. Ahead and astern, the ocean lay almost flat—swells moving with slow, lazy muscle, but no breaking whitecaps, no spray.

Too calm.

He raised his Zeiss binoculars and swept them along the empty horizon. Nothing but a ring of gray: gray sea beneath gray sky, a world stripped of depth and color.

For a moment, he could almost imagine that the war did not exist, that there were no convoys, no escort carriers, no aircraft circling somewhere out there beyond his sight. Just water and steel and cold air.

Almost.

Then he lowered the glasses and the spell broke.

May 23rd, 1943.

North Atlantic. Approximately 540 kilometers southwest of Ireland, according to his navigator’s last careful check of the stars.

It was his fifth war patrol in eighteen months. Four previous patrols had carried him through the bloody prime of the U-boat campaign, the time the propaganda broadcasts called the “happy times.” Müller had never liked that phrase. There was nothing happy about shredded hulls and burning ships, about men screaming in the water. But there had been a feeling, back then, in 1942: that they were winning.

Now, in the summer of 1943, that feeling was gone.

Below him, inside the long steel cylinder of U-672, his crew of forty-eight men moved through the boat with the practiced ease of men who knew every handhold, every bulkhead corner, every squeak of the deck plates.

It was a Type VII boat: the workhorse of the German Navy, the model you saw in postcards and newsreels. She could dive to two hundred meters. She could stay submerged for a day and a half if they nursed her batteries. She had teeth—torpedoes in the bow and stern, guns on the deck—but what kept her alive was not what she carried, but who commanded her.

More than once in the last year, another U-boat crewman on leave had clapped Müller on the shoulder, half envy and half respect in his eyes, and said, “You’re lucky. Your captain knows when to fight and when to run.”

Bernhard Müller never thought of it as luck.

He thought of it as listening.

Listening to hydrophones, to the changing pattern of enemy escorts, to the way Allied convoys no longer behaved like fat, slow herds but like wary animals surrounded by guards with whips and rifles. He listened to his own instincts, too, that tightness in the gut that whispered when something about the sea had changed.

That tightness was whispering now.

The calm was wrong. The silence was wrong.

He lowered the binoculars and closed his eyes briefly, letting the wind scour the salt off his face. Somewhere to the north, beyond that blank horizon line, there was a convoy. Intelligence from BdU—the U-boat command—said as much: a westbound group of seven merchant ships, lightly escorted, a ripe target for a bold commander.

“Her Kapitän?”

The voice came from the hatch at his feet. The first watch officer, Oberleutnant zur See Klaus Schellinger, looked up at him, cap pulled low over his brow against the damp.

“Yes, Klaus?”

“Hydrophone reports no surface screws in our vicinity.” Schellinger’s eyes flicked instinctively toward the horizon, mirroring his captain’s unease. “Sea is very quiet.”

“Too quiet,” Müller said.

He turned his head, listening—really listening—not with his ears, but with that part of his brain that had learned to interpret silence as information.

He heard the soft hiss of air, the low rumble of the diesels, the dull slap of water against the hull.

Then something else.

At first, he thought it was his imagination. A series of faint sounds, faint but distinct, spaced almost regularly.

Plop.

Plop.

Plop.

Not the deep, heavy splash of a single depth charge. Not the distant roll of thunder.

More like someone dropping stones into the sea, one after another, in a pattern.

He stiffened.

“Did you hear that?” he snapped, already reaching for the voice pipe.

Schellinger frowned, cocking his head. Another faint splash carried up over the wind.

“Jawohl,” the first officer said slowly. “That is… strange.”

Müller bent, snatched up the voice pipe and put it to his lips. “Hydrophon!” he barked. “Immediate report on all contacts. What are we hearing?”

Below, in the steel womb of the boat, the hydrophone operator sat with padded cups pressed to his ears, fingertips resting lightly on the gain knobs. He had been listening to the ever-present murmur of the sea, to the distant hum of a merchant ship they had heard hours earlier, fading out of range.

The captain’s voice jolted him. He straightened, narrowed his eyes, listened harder.

There was static. The sigh of current. The soft rumble of U-672’s own screws. But no distinct propeller beats, no high-pitched drone of aircraft engines overhead.

He swallowed, adjusted the gain again, then spoke into his own mouthpiece.

“Her Kapitän, the instruments show nothing. No ship signatures, no aircraft, just… water. I hear nothing like depth charges. Only, perhaps, splashes in the air.”

The words rose through the voice pipe and found Müller standing in the conning tower, jaw tightening.

He had been trained in every aspect of submarine warfare the Kriegsmarine could cram into a man in the late 1930s.

He knew the patterns.

Depth charges had a certain ritual: the whump of launch, the waiting seconds, the hollow booming detonation far below.

Aircraft had their own music: the rising whine of engines, the sudden howl of a dive, the roar and crash of bombs or gunfire.

Submarine warfare had logic. Every threat had a sound, a sequence, a familiar script.

This sound did not.

“Hard to starboard,” he ordered sharply. “Dive to sixty meters. Silent running.”

Schellinger relayed the orders instantly.

Below, claxons blared, echoing along narrow passages. Men scrambled to stations with the fast, controlled urgency of people who have drilled for this moment so many times they could find their places in pitch darkness.

Diesel engines cut off, leaving a momentary ringing silence in men’s ears. Then the electric motors took over with a lower, smoother hum. Ballast tanks vented; water roared into the space where air had been. U-672’s bow dipped.

In the conning tower, Müller felt the angle shift beneath his feet, the sense of the boat nosing downward into the twilight underworld where sunlight could not reach.

He forced his fingers to uncurl from the rail.

At thirty-one, he was old for a front-line U-boat captain. So people said. He had been at sea since his early twenties, long before most of the wide-eyed boys now filling the ranks had even seen a torpedo. He held the Iron Cross First Class. Seven ships sunk, thirty-eight thousand tons of Allied shipping torn from the ocean’s surface.

But that was history. History did not stop the splashes outside.

He descended the ladder into the control room.

It was a low, cramped space, all pipes and gauges and men. The air smelled of oil, sweat, tobacco, and steel that never quite dried. Red battle lights cast everything in bloody shadow.

Schellinger stood by the periscope well, bracing himself as the boat tilted. The helmsman sat at his wheel, eyes flicking from compass to depth gauge.

“Report,” Müller said.

“Depth fifteen meters and increasing,” the planesman called. “Angle ten degrees down.”

“Level off at sixty,” Müller said.

He moved toward the chart table, where the navigator was already pencil-marking their new course and estimated position.

In the corner, the hydrophone operator sat rigid, headphones clamped, every muscle focused on the faintest whisper from outside.

He heard it first—the new sound.

A low, steady beat.

Thrum-thrum, thrum-thrum.

Twin screws.

“Contact!” he snapped. “Single escort. Bearing red one-three-five. Range… difficult to judge. Approaching. Speed perhaps eighteen knots.”

Schellinger’s head came up. “Her Kapitän, destroyer contact, bearing red one-three-five. Single screw, eighteen knots, from the north.”

Müller nodded, the lines in his forehead deepening.

A destroyer, out here, at that speed and bearing, meant only one thing: a convoy.

The escort, he knew, would be out in front or to the side of the merchant ships, ranging ahead like a sheepdog. If the destroyer was here, the real prize was somewhere nearby.

He imagined, in his mind’s eye, the shapes of freighters loaded with fuel and food and ammunition, steaming in convoy columns. The lifeblood of Britain.

That was why he had come to the Atlantic: to cut that bloodline. To sink tonnage, as BdU always said. To starve the island.

“Full stop,” he ordered calmly. “All crew to minimum noise. Silent running. We wait.”

The electric motors slowed, then stopped. U-672 hung in the water like a suspended bullet, bow slightly down. Men held their breath without meaning to, as if their lungs themselves might make too much noise.

The hydrophone operator listened to the destroyer’s approach.

At first, the beat was faint, then stronger. The sound split into two distinct signatures.

“Correction,” he said softly. “Twin screws. Likely a British Flower-class corvette, not destroyer. Range three thousand meters. Still closing.”

Müller’s mind ticked through what that meant.

Flower-class corvettes were purpose-built convoy escorts—small, slow, but well-armed for anti-submarine warfare. They lacked the speed of fleet destroyers, but their crews were often experienced, their sonar sets increasingly good.

A Flower-class meant a proper convoy.

It meant opportunity.

It also meant risk.

He pictured again the geometry of the situation: U-672 at sixty meters, engines dead, drifting slowly. The corvette above, sweeping with sonar, listening. The convoy beyond, out of reach—for now.

If he could remain undetected while the escort passed overhead, then once night fell completely and the corvette moved off to her patrol station, he might surface, sprint, and make his attack.

The old doctrine. The one that had brought them so much success.

Night surface attack was the U-boat commander’s art, the skill that separated the aces from the dead.

On the surface, at night, a U-boat was not prey.

It was a predator.

Faster than most escorts, lower in the water, almost invisible, it could slide in alongside a convoy, fire torpedoes at point-blank range, and disappear in darkness before the escorts could find it.

Up until a few months ago, that doctrine had worked.

He refused to believe it had suddenly become suicide.

“Maintain depth,” Müller said. “Hold at sixty. Silent running. Report any change.”

He settled himself into the narrow command chair. His men cleared him a space without being asked.

Time began to stretch.

The destroyer’s screws grew louder.

Seconds became long. Minutes became heavy.

Somewhere in the boat, a man swallowed too hard, the amplified click echoing. Someone shifted his weight too quickly and bumped an elbow. A petty officer’s whisper cut him off with a quiet curse.

“Bearing red one-zero,” the hydrophone operator murmured. “Range one thousand meters and closing.”

Müller nodded, though the operator couldn’t see him. He laid his hands flat on the chart table, feeling the faint vibrations through the wood and steel.

One thousand meters.

At that distance, if the escort detected them and dropped a pattern of depth charges, they would have almost no warning.

“Five hundred meters,” the operator said, voice thinner now. The whole boat could feel it: the deep, thrumming roar of the escort’s turbines, vibrating the water itself.

The chart table trembled. A wrench hanging from a pipe shivered, clinking faintly.

“Two hundred meters. Directly above.”

Müller stared up at the ceiling, at the mass of water and hull and danger between him and the ship overhead.

This is the moment, he thought. This is when they drop.

He imagined the corvette’s crew above, in their own cramped sonar room, watching a glowing trace, listening to echoes. A petty officer calling ranges and bearings. A captain deciding whether the shadow on his screen was real or noise.

Silence.

The escort’s screws grew louder, impossibly loud, then began to recede.

No rush of water from falling charges. No distant concussions. No rolling thunder.

The sound of the twin screws dwindled slowly to a murmur, then to nothing.

“Escort passing,” the hydrophone operator said, his voice colored with relief he tried to hide. “No attack pattern. Moving away.”

Around the control room, men exhaled in a whispered rustle. Someone murmured “Gott sei Dank” under his breath.

Müller let himself breathe out slowly. The corvette had not detected them.

Their position remained secret.

In another hour, when full darkness embraced the Atlantic, he could surface. He could hunt.

That was all he needed.

What he did not know—what no U-boat commander in that moment could have known—was that the corvette was not alone.

Behind it, HMS Oriel was maneuvering further ahead into an intercept position.

Overhead, vectored by high-frequency direction-finding of German radio traffic and intelligence from convoy escorts, a Lockheed Hudson aircraft was altering its patrol course to overfly this patch of ocean at dusk.

The net around him had already begun to tighten.

In the command chair, Müller checked his watch.

Another ninety minutes until full dark.

Another ninety minutes until the rules of the game, as he understood them, would favor him again.

He did not know they would kill him instead.

The hours between detection and attack are the longest in submarine warfare.

The boat remained at sixty meters, no engine noise, just batteries powering vital systems, men moving only when necessary.

They spoke in low voices, if at all. They played games in their heads: counting seconds between faint sounds, imagining how far the convoy might have moved by now, planning firing solutions in their minds.

The air grew thicker. Not dangerous yet, but stale. The smell of men and machines mingled with the faint iodine tang of seawater.

Müller sat, eyes closed but brain racing.

His thoughts drifted back, uninvited, to the early days. To 1941, when he’d been a watch officer under another captain on a different U-boat, learning the art of approach and attack.

Back then, the ocean had felt empty of enemies. Escorts were fewer, their radar weak. Convoys sailed under-protected. A skilled U-boat could carve into them like a wolf into a flock.

He remembered standing on a conning tower in the Bay of Biscay, wind whipping spray into his face as the dawn lit the sky, the glow of three burning freighters painting the clouds orange behind him. The captain, a hard-eyed man from Hamburg, had clapped him on the shoulder and laughed.

“You see, Bernhard? The Atlantic is our hunting ground. As long as we are daring, as long as we strike first, these Brits have no answer.”

In late 1942, BdU’s communiqués had trumpeted numbers: 119 ships sunk in November alone, over 700,000 tons. They’d called it the tonnage war, and every successful patrol bolstered the illusion that the equation was simple: sink more than the enemy can build.

But 1943 had brought something else.

On shore, in Lorient and St. Nazaire, in the smoky mess halls where crews swapped stories on brief leaves, rumors spread.

Convoys were being rerouted away from wolf packs more frequently, as if someone on the other side knew where they would be.

Boats that had once attacked on the surface with impunity now reported being swept by searchlights or strafed by aircraft in the dead of night.

There were whispers of new radar, of Allied device that could detect the faint emissions of the U-boats’ own radios from hundreds of kilometers away.

“Secret weapons,” some men said.

Other commanders dismissed it. “Bad luck,” they said. “A few unfortunate patrols. The Atlantic is big. The enemy gets lucky sometimes, just as we do.”

Müller had listened, said little, and gone back to sea.

Every patrol he survived after that, he counted as proof that his instincts—aggressive when aggression mattered, cautious when caution meant living to hunt again—were still enough to thread the needle between rumor and reality.

Now, as he sat in his chair at sixty meters, he wondered if that confidence had been arrogance in another uniform.

“Depth holding steady,” the planesman murmured.

“Very well,” Müller said. “Maintain.”

Time crawled.

Darkness slowly claimed the surface.

At 20:00 hours, after one last careful sweep with hydrophones and a final check of his chart, he decided.

“Prepare to surface,” he ordered.

The words carried through the boat like a release of pressure. Suddenly there was movement again: men shifting, systems coming fully alive, ballast ready.

The order came: “Blow main ballast.”

Compressed air screamed into tanks; trapped seawater roared out.

U-672’s bow tilted up. The sense of weight changed as she rose.

Men who had been living in red light and stale air for hours felt the subtle lightening that came with approaching the water’s surface, that mental trick that made you feel you could breathe deeper simply because, somewhere above, there was sky.

The boat broke through, steel slicing the surface.

The deck watch was already at the hatch. Müller climbed with them, shoulders brushing the metal, then emerged into the cool night.

He inhaled deeply. The air up here was colder, fresher, scrubbed by wind.

Above, the sky was a smear of stars. No moon. Perfect.

His eyes, long adapted to the gloom below, drank in the faint details: the glimmer of starlight on wavecrests, the darker patches of cloud, the dim, hulking shapes on the horizon.

There.

Convoy.

He lifted his binoculars and pressed them to his face.

Seven merchant ships, by his count. Their silhouettes staggered in two columns, the telltale shapes of freighters plowing westward, bow waves glinting silver. Between them, like a shepherd dog pacing his flock, a squat shape that could only be an escort.

The corvette was still patrolling to the north, where she thought the danger lay.

They had slipped beneath her.

“Battle stations,” Müller said quietly, though his words carried like a cracked whip. “All torpedo tubes prepare for surface attack.”

The order ran below. Men who had been motionless leapt into action. In the forward torpedo room, sailors pulled off covers, checked pressure readings, confirmed that the eels were primed—two G7e electric torpedoes in the bow tubes, silent-running, leaving no telltale wake.

“First watch, with me,” Müller called. “Second watch, stand ready.”

Schellinger moved to the attack periscope, though it was not yet needed; up here, binoculars and his own eyes would suffice. The navigator, charts rolled under his arm, squeezed through the hatch to join them, flattening himself against the steel to avoid the swing of the UZO binocular pedestal.

The sea around them looked empty. To a human eye, it was.

But in that emptiness, metal and intention moved invisibly.

Müller watched the convoy, mind turning fast.

Range to lead merchant, he estimated, around twelve thousand meters. The torpedoes, at thirty-five knots, would need roughly two minutes to run that far.

In those two minutes, the convoy would move forward as well, closing part of the distance. His firing solution would have to account for relative motion, angle on the bow, bearing spread.

“Estimate to nearest ship?” he called without removing the glasses.

“Approximately twelve thousand meters,” Schellinger answered, already scribbling numbers. “Destroyer bearing red three-four-zero, eight thousand meters away, moving northeast.”

“Solution?”

“Ready in thirty seconds.”

Müller allowed himself a brief, hard smile.

Perfect.

The escort was on the far side of the convoy, attention directed outward. By the time they reacted to his first torpedo hits, he could fire a second salvo, maybe a third, then crash-dive and vanish.

He did not think of the crews of those merchant ships. Not specifically.

They were numbers.

Tonnage.

Cargo.

Ammunition that would not reach the front. Fuel that would not burn in Allied tanks. Food that would not feed British cities.

Every hull he sank was a subtle pressure on the enemy’s throat.

In the cramped spaces below, the torpedo crews whispered to one another. Some made the same jokes they always made. Others kept silent, swallowing dry. The veteran among them, a machinist’s mate named Weber, patted the side of the nearest torpedo like a horseman calming a mount.

“Let’s eat, boys,” he murmured. “Two more and we go home.”

“Solution ready,” Schellinger called.

Distance, bearing, course—all translated into numbers on a firing calculator.

Müller’s right hand rose.

“Bow tubes one and two,” he said. “First salvo. Fire.”

The boat shuddered faintly as compressed air punched two torpedoes out into the dark sea.

They slid away from the bow, dove to set depth, and began their run—silent, invisible killers heading for the dim shapes of merchant hulls.

Müller turned his head.

“Prepare second salvo—”

He never finished the sentence.

The sea erupted around them.

Not ahead, where his torpedoes were racing.

All around.

The first splash was so close that droplets of saltwater hit his face.

Huge columns of water leapt into the air, one after another, in a pattern so precise it felt unnatural: directly ahead, off the bow; to port; to starboard; astern.

Blinding sprays, each accompanied by a shriek in the air just before impact, as if something solid had sliced through the night at immense speed.

For a fraction of a second, his brain tried to fit the sound into something he understood.

Depth charges, launched from throwers off an escort’s sides, usually splashed in arcs, then sank, giving them time to get away from the ship that launched them. You heard the launch, saw the splashes, then waited for the delayed thump of explosions at depth.

This was different.

These explosions were not delayed. Not heavy, rumbling echoes from deep below.

They were hard impacts, sharp and immediate, like sledgehammers hitting steel.

“Crash dive!” Müller shouted, voice tearing his throat. “Hard to starboard! All hands brace for impact!”

He grabbed for the rim of the conning tower hatch even as he barked.

But in that instant, he understood something terrible:

There was nowhere to run fast enough.

The water beneath them was three hundred meters deep. In theory, they could dive, try to slide under the attack. But those projectiles were already in motion. Whatever weapon the enemy had used, it had been aimed at where they were now, not where they had been.

The first projectile slammed into the conning tower itself.

It wasn’t large—maybe a kilo of metal and explosive—but it was moving at around four hundred meters per second when it hit.

It punched through the outer plating as if the tower were made of paper, not steel.

The blast it triggered inside the structure tore through the conning tower and into the pressure hull beneath, ripping seams, blowing out instruments, turning shards of metal into shrapnel.

Müller didn’t so much hear the explosion as feel it: a violent, wrenching spasm in the bones of the boat, a fist that grabbed U-672 and twisted.

He felt himself thrown sideways, his shoulder smashing into metal. For a moment the world was nothing but black, then a roaring rush of icy water as something above and behind him gave way.

The conning tower was filling with sea.

Men shouted, the words snatched away by the rush of water and the ringing in his ears.

He tasted blood, salt, oil.

Below, in the forward compartments, the second hit smashed through like an angry god. One moment the torpedo room was cramped but intact; the next, a section of hull near the bow simply ceased to exist, replaced by a roaring hole in which darkness and water were the same thing.

The sea did not trickle in. It slammed. It punched men off their feet, crushed them against bulkheads, flooded lower spaces in seconds.

The lights flickered, then went out. Red emergency bulbs came on, casting the torrent in eerie, pulsing color.

“Flooding! Forward compartment flooding!” someone screamed into a voice tube, even as water tore the words from his mouth.

In the control room, gauges spun wild. The depth meter lurched, showing a sudden downward spike as the bow filled with water and dragged the boat down.

“Mittelraum, seal forward bulkhead!” an officer shouted. “Close it! Close it now!”

Men threw themselves at the wheel, cranking the watertight door shut as fast as they could. Behind it, water pounded like fists.

In the conning tower, Müller grabbed for the voice pipe, fingers slipping on wet metal.

“Flood all compartments,” he rasped, coughing. “Get the men up. We’re sinking.”

He didn’t think about whether that was standard procedure.

There was no procedure for this.

The sound of more splashes came through the chaos. Another pattern of projectiles hit the sea and drove down, searchers feeling blindly for the shape of his dying boat.

Then a third.

A fourth.

Each one a cluster of small, self-propelled, contact-detonating bombs, each thrown in a pattern designed to carpet a circle of ocean fifty meters across.

Each one a part of a weapon system he had never even heard of.

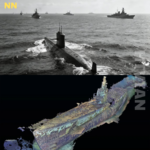

The British called it Hedgehog.

He would only learn that name later.

Right now, all he knew was that U-672—the boat he had brought through storm and shell, the steel womb that had been home and weapon for eighteen months—was coming apart around him.

Bulkheads groaned.

The boat’s angle steepened, bow yanking down as tons of water poured in.

The stern lifted. Men lost their grip and tumbled, slamming into fellow crewmen, into pipes, into hard edges.

In the aft engine room, men who had been idling during silent running were suddenly waist-deep in swirling water, grabbing for emergency gear.

Someone in the control room tried to blow ballast, to force air into tanks and arrest the dive. Valves squealed. Air rushed. Something responded—but not enough. The weight of water in the bow was too great.

The pressure that had held the Atlantic at bay for the last hours, days, months of their lives was now being violated in dozens of places at once.

Steel shrieked.

Nuts sheared.

Seams split.

The U-boat’s carefully maintained envelope—the thin shell that separated men from death—dissolved.

“Up! Everyone up!” Müller shouted hoarsely, though he wasn’t sure anyone could hear him, not with the water’s roar and the screams. “Get them up!”

Some obeyed. Some didn’t have a chance.

The second pattern of projectiles hit, one slamming against the already mangled hull. The explosion felt like a final punch to the gut.

Somewhere around twenty seconds had passed since the first hit.

The boat was sinking like a stone.

In those seconds, individual lives played out tiny, desperate dramas.

The hydrophone operator, whose name was Dieter, felt the floor tilt under him. He grabbed for the edge of his stool, then for the bulkhead, failing at both and collapsing against the steel. He thought of the farmhouse in Bavaria where his parents still lived, where he had last tasted fresh milk.

The machinist Weber found himself suddenly pinned beneath a heavy torpedo loading tool that had broken free. He could not feel his legs. He could feel water, shockingly cold, creeping up his chest.

The young cook, barely nineteen, had never learned to swim. He clung to a handrail, sobbing loudly, ashamed even as terror took him.

In the conning tower, the sea was up to Müller’s knees, then his waist, then his chest. The cold cut through the numbness in his injured shoulder like a knife.

He tried to climb, to haul himself toward the hatch.

Part of his mind, the calm, tactical part, knew that if the boat went below a certain depth full of water, the pressure would crush it like an egg.

The only way to live was to reach the surface first.

“Raus!” he gasped, shoving a younger sailor toward the ladder. “Out! Swim!”

The man stared at him wide-eyed, then scrambled up, boots slipping.

The next seconds blurred.

He felt the boat’s tilt change.

Some emergency ballast blast must have taken hold, or perhaps the weight of water equalized enough that the boat no longer dove like a stone.

Either way, the conning tower hatch was suddenly closer than it had been.

He grabbed the rungs.

His lungs burned. He didn’t remember taking a breath.

His hands moved, one after another, hauling himself upward. A wave of water slammed into his back, trying to peel him off the ladder. He clung on, teeth bared.

Above, a circle of barely lighter darkness marked where the hatch had been blown or torn open.

He lunged for it.

Then he was out, spat into the night like a seed from a crushed fruit, U-672 belching water and air beneath him.

The world changed again: from steel and red light and choking noise, to open, freezing air and the vast black dome of sky.

He barely had time to register the stars before the sea took him, the Atlantic folding over his head like a lid.

He tumbled, weightless, then heavy, blind, then saw faint specks of light when he surfaced, coughing, choking.

The cold hit him fully, searing his skin.

He sucked in air that tasted of smoke and salt and oil.

Around him, the sea was full of wreckage: planks, shards of metal, floating bits of cork insulation, the occasional shape of a life jacket, a human arm waving or not waving.

Screams cut across the water.

“Mutti!” someone cried, voice cracking.

“Hier! Over here!” another shouted, switching instinctively to English, then back to German.

He grabbed for reflex, finding his fingers closing around a wooden grating that must have once been part of the deck. It bobbed, half-sunk, but it held enough air to give him something to cling to.

He wrapped his arms over it, his body already losing heat, his mind trying to catch up to the fact that something he had never seen, never even imagined, had just destroyed his whole world in less than two minutes.

U-672 sank in ninety-four seconds.

Thirty-six men, including Müller, reached the surface.

Twelve did not.

The water was three degrees Celsius.

Not cold enough to kill immediately, like Arctic water. But cold enough that hypothermia started as soon as skin met sea. Muscles stiffened. Fingers numbed. Thoughts slowed.

Müller floated, legs trailing, boots heavy, his uniform soaking up water. Each breath came with effort.

He had learned about cold-water survival in training. On a blackboard, in a lecture hall. Numbers. Charts. How long a man could expect to remain conscious. How long before the body shut down.

Those had been abstract then.

Now they were the ticking of a different kind of clock.

Around him, the screams thinned as voices either drifted farther away or their owners stopped shouting to preserve strength.

He heard someone singing a hymn, soft and wavering. He heard curses hurled at distant, unseen enemies.

He heard his own teeth chattering.

Time passed in jerks, not smoothly. One moment he was staring at the stars, thinking of nothing. The next, he was aware of a distant shape growing larger on the horizon—a darker blot in the darkness, moving against the pattern of the waves.

A ship.

He blinked, tried to focus.

It drew closer. He could see a bow wave, lights moving along a rail, the silhouette of a mast. A small vessel, not a convoy merchant, not a big destroyer.

A trawler.

HMS Oriel, though he wouldn’t know the name until later. An armed trawler turned escort, part of the net that had just closed around him.

A shout came from its deck, a human voice cutting across the water in English. He couldn’t make out the words.

Ropes hit the sea near him, splashing. So did something like nets. He saw other men, shadows in lifejackets, flailing toward them.

He forced his limbs to move. The grating beneath him shifted and nearly rolled, dumping him deeper into the water. He clung, coughing.

Another rope appeared within reach, trailing a buoy.

He lunged for it, fingers barely closing. For a moment he thought he’d missed, then the rope burned against his palm and he clutched it like a lifeline—because it was.

Hands on the trawler’s deck hauled. He felt himself towed toward the hull, bouncing off it, knees slamming into steel. Hands grabbed his jacket, his shoulders, dragged him upward.

Cold air, colder than the water, closed around him.

He rolled onto a deck slick with seawater and oil and lay there, his chest heaving.

Above him, silhouetted against the dim sky, stood a sailor in a Royal Navy jumper, breath steaming. The man looked down at his soaked, gray-uniformed prisoner and didn’t kick him, didn’t curse.

He just shouted over his shoulder, “Another one here!”

More survivors were brought aboard. Thirty-six in all, out of forty-eight.

Twelve names that would never again be called at muster.

Twenty minutes later, Müller stood—or rather, shivered—on the deck of HMS Sharpshooter, wrapped in a scratchy British naval blanket. His teeth still chattered uncontrollably. His fingers felt like someone else’s.

He looked smaller than he had on the conning tower, his authority stripped away with his cap and coat. Now he was just another prisoner of war, one more face among many.

An older British officer approached him. His uniform, though worn, was neat; his posture carried the easy confidence of someone whose side was winning.

“Kapitanleutnant Müller?” the man asked in careful German.

Müller forced his jaw to unclench long enough to nod. “Ja.”

“I am Captain James McIntyre, Royal Navy. Escort group commander.” The British officer’s German had the slightly odd rhythm of someone who had learned it properly in a classroom, not in barracks.

He did not sound cruel. Or triumphant. Just… tired.

“Your boat,” McIntyre said, “was caught by our newest weapon.”

He paused, studying Müller’s face, perhaps wondering if the man understood what had hit him.

“We call it the Hedgehog.”

The word meant nothing to Müller. A small animal, in peacetime. Nothing that could tear steel.

McIntyre continued, perhaps sensing the confusion.

“It’s a forward-firing mortar system. When you attempted to surface for a night attack, you were detected on sonar. We fired twenty-four shaped charges in a pattern ahead of the ship. You never had a chance.”

Müller stared at him.

He heard the words. He understood each individually. Together, they painted a picture that filled in the blanks of the last minutes aboard U-672.

Forward-firing.

That meant the attacking ship did not have to sail over the suspected U-boat position and drop charges blindly, losing sonar contact as the bubbles and turbulence of explosions masked all echoes.

They could keep the submarine on their sonar screen, tracking its depth and bearing. Fire ahead. Walk the pattern right onto the contact.

Shaped charges.

Not big, blunt depth charges set to explode at random depths in the hopes of being close enough.

Pointed, contact-fused spikes that didn’t have to be near. They only had to hit.

“We detected you on sonar,” McIntyre repeated. “We kept you on sonar while we attacked. That is the key, I think. The old pattern—run over, drop, lose contact, guess where the U-boat might have gone—that is finished. We can see you now. The Hedgehog lets us strike without taking our eyes off you.”

Müller said nothing.

His mouth was too dry, his mind too crowded.

He thought of all the nights, all the attacks, all the times he had relied on a simple truth: that once he dived, the enemy was half-blind. That their sonar was clumsy. That depth charges were imperfect. That the ocean itself—vast, noisy, full of layers and currents—was on his side.

That doctrine had died in ninety-four seconds.

“This is the third U-boat we’ve sunk with Hedgehog in three weeks,” McIntyre added quietly. “The message will reach your high command soon, I’m sure.”

He looked out across the gray sea, his breath lingering in the air.

“The old rules of submarine warfare are finished, Kapitän. Your boats can no longer hunt convoys on the surface at night with impunity. You can no longer rely on darkness. We can see you, track you, and attack you without losing contact.”

The words were not spoken with malice. They sounded, instead, like a grim statement of fact from a man who knew what that fact meant—in lives saved and lives lost.

Müller’s hands tightened on the blanket.

He understood.

Not all the details. Not yet.

But he understood the shape of it.

For three years, U-boat commanders had believed that boldness, training, and determination could offset almost any deficiency in numbers.

Now, one new weapon had just turned their greatest strength—night surface attack—into a liability.

A surfaced U-boat, in May 1943, was no longer an invisible hunter.

It was a target.

Later, when his clothes were dry and his body had stopped shaking quite so violently, Müller sat alone in a cramped, borrowed cabin—what had been McIntyre’s small office aboard Sharpshooter.

Outside the porthole, gray light seeped over a gray ocean. Somewhere aft, one of the British escorts’ guns thumped a practice round, the sound muffled by steel.

On the small desk in front of him sat a mug of tea he had barely touched.

His head throbbed dully. His left shoulder ached where he had slammed it into metal. There was a cut on his right cheek he did not remember receiving.

On the opposite bulkhead, someone had stuck a small photograph: a woman and two children standing in front of an English row house, all in black and white. The edges were worn where fingers had held it many times.

He stared at it for a long time.

It occurred to him, distantly, that somewhere in Germany, his own wife had a similar photograph of him. Or perhaps she did not, if the censor had not yet allowed news of his missing status to pass.

The door opened with a soft click.

McIntyre stepped in, ducking his head slightly. He carried a folder under one arm.

“We are transferring you to a larger ship later today,” he said without preamble. “You’ll be processed as a prisoner of war. Geneva Convention, all that. You will be properly treated.”

Müller nodded once, still staring at the photograph.

“You may think it strange,” McIntyre went on, “but we try to explain ourselves—to officers like you. You’d do the same in our position, I think. It’s not about interrogation. More about… context.”

He sat opposite, opened the folder, then closed it again, as if thinking better of reading from notes.

“Your BdU will receive reports,” he said. “They’ll see the numbers. Dozens of U-boats lost in this month alone. They will, I suspect, blame it on shortages, on errors, on the gods of war.”

He looked directly at Müller.

“But that is not it, is it?”

Müller met his gaze reluctantly. “What is it, then?” he asked, his voice raw.

“It is the system,” McIntyre said simply. “The way our tools now work together.”

He counted them off, not boastfully, just clinically.

Centimetric radar sets that could pick out a U-boat’s conning tower at thirty kilometers, regardless of weather, day or night.

High-frequency direction-finding stations on land and at sea that could triangulate the source of German radio transmissions, narrowing patrol fields.

Escort carriers—small aircraft carriers attached to convoys—that flung off patrol planes like the Hudson that had helped find U-672’s general area before Oriel and Sharpshooter moved in.

Improved sonar, more sensitive and better-handled, that could hold a submerged contact under continuous observation.

And, now, Hedgehog.

A forward-throwing mortar that fired twenty-four small bombs in a circular pattern ahead of the ship.

Each piece was dangerous by itself.

Together, they were lethal.

“Sonar finds you,” McIntyre said. “Radar confirms you. Huff-Duff”—he used the English nickname for high-frequency direction-finding—“narrows where you might be when you transmit. Aircraft harry you, force you down or keep you under observation. And when one of our escorts finally gets a firm solution on you, he doesn’t have to guess anymore. Hedgehog lets him attack without blindly charging over your last known position. He can stay on you.”

He splayed his fingers on the desk, as if spreading out the system itself.

“Each component feeds the others. Each makes all the rest more effective. That is what has changed.”

Müller swallowed.

Perhaps, he thought, if he had heard this three weeks ago, he would have reacted with defiance. Called it propaganda. Claimed German science would produce its own miracles.

Now, with U-672 lying shattered on the seabed beneath them, the words had the solid weight of experience.

He remembered the strange splashes he had heard hours before, those first, inexplicable plops in the water.

The hydrophone operator had heard nothing on his instruments because Hedgehog didn’t need to warn its target. It didn’t have to drop big barrels overboard and let them fall.

It lobbed small bombs forward, silently arcing through the air until they slammed into the water all around the contact.

No warning.

No counting seconds.

Just impact.

“We have lost boats before,” Müller said slowly, his German thickened by exhaustion. “One or two at a time. Ambushes. Lucky hits. Mines. It was always… part of the cost.”

He shifted, the blanket rustling.

“But this…”

He thought of rumor. Of other captains who had not returned from patrol. Of whispers among crews about a new phase of the war.

“Your Hedgehog has sunk three of us in three weeks,” he said quietly. “How many will it sink before my superiors understand?”

McIntyre did not answer. Perhaps he didn’t know the exact number yet himself. The tally would be written later: forty-seven U-boats ultimately destroyed by Hedgehog attacks.

For now, he said only, “Black May. That is what some in the Admiralty are already calling this month. For you. For the U-boats.”

He closed the folder.

“I’m not asking you to like it, Kapitän. I’m not asking you to admire it. But I think you are a thoughtful man. I wanted you to see. The battle is not about more guns, or thicker armor, or who has more courage. It is about whose system of weapons and sensors and tactics fits the world better.”

He stood.

“My war with you is over,” he said. “But your war with yourself may just be beginning.”

He left the cabin without waiting for a reply.

Müller sat in silence.

Outside, the gray sea rolled.

Inside, the realization settled slowly, like silt in still water:

His boat had not simply been sunk by a more powerful explosion.

It had been erased by a different kind of war.

The trains that carried prisoners of war across Scotland and England in 1943 had their windows painted over.

Still, between the edges of the black paint and the rattling frames, a man could sometimes see glimpses: a green hillside, a stone farmhouse, children waving at the passing blur of carriages.

Müller watched those slivers of another country and felt something in his chest twist.

He had not expected to feel envy.

But there it was, sharp and bitter.

Those people outside the window had no idea what lay on the bottom of the North Atlantic. No idea what it sounded like inside a steel tube as it came apart.

They did not need to know.

Their safety, he realized, depended on the fact that men like him had failed.

The thought was strangely liberating and crushing at the same time.

The POW camp in Canada—where he eventually ended up after a series of transfers—was not the brutal cage some propaganda posters imagined.

It was cold in winter, hot in summer, and surrounded by barbed wire and guards. But the food was regular. The bunks were adequate.

Inside the wire, there was a strange community: U-boat officers, Luftwaffe pilots, infantry majors, all of them men whose wars had ended whether they wanted them to or not.

They played soccer. They argued politics. They told stories.

At night, when the barracks grew quiet, they lay on metal cots and stared at dark rafters and thought about things they rarely spoke aloud.

Some clung to the old narrative: they had been betrayed by politicians, by lack of resources, by fate.

“We just needed more boats,” one former commander insisted one evening, thrusting his chin out. “If we’d had another hundred Type VIIs, if production had not been disrupted—”

“More boats to be sunk?” Müller asked calmly.

The other man glared at him. “We’d have overwhelmed them. They couldn’t have escorted every convoy.”

“And if they can see every boat we send?” Müller asked. “If their radar sees us when we surface, their aircraft find us when we flee, and their sonar holds us when we dive? What then?”

He spoke in a low voice so as not to wake the men already asleep, eyes closed against memories.

The other commander opened his mouth, then closed it.

“Bad luck,” he muttered finally. “This year, at least.”

Müller almost laughed.

He had felt the Hedgehog’s pattern crash around him, heard McIntyre’s explanation, seen the barely concealed fatigue in the British captain’s eyes. He did not believe in luck any longer—not in the way some of his comrades meant it.

Later, when the lights went out and the barrack sank into a quiet broken only by snoring and the occasional murmur in sleep, he lay awake.

He thought of something his father had told him when he was a boy, long before uniforms and war.

“Courage is good,” his father had said, a mechanic with grease under his nails and tired eyes. “But courage is not enough if your opponent has a better tool for the job.”

At the time, they had been talking about hammers and rivet guns.

Now the words echoed in a different key.

In 1940, courage and training and daring had seemed to be everything. His instructors had hammered into them that a well-handled U-boat could defeat any escort. That their steel claws, their torpedoes, were the finest weapons afloat.

They had treated technology as an enhancement to courage—as something that made brave men more effective.

In May 1943, he had discovered something else:

Technology was not an accessory.

It was the war itself.

Every ship they had built, every tactic they had developed, every brave man they had sent to sea—every one of those could be rendered obsolete in a matter of months by an enemy system that was better integrated, better coordinated.

Not just a better torpedo, or a bigger gun.

A better network.

The Allies had built that network, piece by piece, while German command still thought of the Atlantic as a place where individual aces could shape the outcome through daring alone.

He could not shake that idea.

In the camp, he tried to put it into words when younger officers asked him why his boat had been lost.

“It was not the Hedgehog alone,” he would say quietly. “That was only the instrument that struck the final blow. The real weapon was the way their tools worked together. Their radar, their sonar, their aircraft, their ships, their direction-finding, their communications. Each made the others stronger.”

“Then we lost because we had fewer factories,” one young Leutnant countered.

“No,” Müller said. “We lost because we did not understand that the war had changed.”

He did not expect his words to change minds.

Most of his countrymen would hold on to whatever explanation let them sleep at night.

Bad luck.

Not enough boats.

Traitors.

Anything but the thought that their own system had been inferior.

He, on the other hand, could not un-know what he had seen in those last ninety seconds aboard U-672.

A U-boat, once the terror of the Atlantic, turned into a helpless target by a weapon she had never been designed to face.

When the war ended and the wire finally opened, Müller returned to a Germany that barely resembled the country he had left.

Cities were broken teeth. Vast areas were piles of brick and ash. Flags and slogans had changed.

He did not wear his Iron Cross in public.

He went to see his wife in a small town that had been spared the worst bombing. They stood together in the doorway of a cramped apartment and looked at each other for a long time before either spoke.

At night, when she slept, he sometimes woke suddenly, certain he could hear the rushing roar of water smashing into bulkheads. He would lie there in the quiet, heart pounding, until the sound faded and he remembered that the only waves near them now were the gentle ones on a river outside town.

Once, years later, his son—twelve years old and full of questions—asked him about the war.

“Is it true, Papa,” the boy said, eyes shiny with the romantic curiosity of youth, “that U-boats were invisible? That they could strike and vanish like ghosts?”

Müller looked out the window.

The street outside was ordinary. A bicycle leaned against a lamp post. A neighbor walked past carrying a loaf of bread in a paper bag.

“They were invisible,” he said slowly, “for a while.”

He hesitated.

He could have told a story of daring, of ships sunk, of evasions. Many former officers did.

Instead, he told his son about May 23rd, 1943.

About the strange splashes.

About the destroyer’s screws passing overhead without attacking.

About the confidence he had felt as they surfaced into a moonless night, believing old rules still applied.

About the enormous, precisely spaced splashes around his boat.

About the ninety-four seconds that followed.

His son listened, wide-eyed, a crease between his brows.

“But why… why couldn’t you escape?” the boy asked. “Couldn’t you dive deeper? Turn away?”

“We tried,” Müller said gently. “But by then, we were already inside their pattern. The geometry was against us. Their weapon was designed for that situation. Ours was not.”

He searched for words the boy would understand.

“Imagine two men fighting,” he said. “One has a sword. One has a gun. The man with the sword may be stronger, braver, better trained. He may have killed many men before. But if he tries to fight the man with the gun at the distance where the gun is best, his skill with the sword does not matter.”

His son frowned, thinking.

“So you’re saying the U-boats were the swords?”

“Yes.”

“And the Hedgehog was the gun?”

“Not just the Hedgehog,” Müller said. “Everything they had built. The Hedgehog was just the bullet that hit us.”

The boy was quiet for a moment, then said, “That doesn’t seem fair.”

Müller smiled faintly. “War is not about fairness,” he said. “It is about who understands the battlefield better.”

He did not tell his son everything.

He did not describe the sound of men drowning.

He did not describe the exact twist of metal when a keel fails.

But he told enough that, years later, when that boy grew into a man living in a Europe bound more by trade than torpedoes, he would remember that his father’s war had ended not because his father’s courage failed, but because the world had changed faster than his commanders understood.

In official German naval histories written after the war, the loss of U-672 rated only a few lines.

On May 23rd, boat sunk in North Atlantic by Allied surface forces. Some survivors.

The numbers buried the details.

Forty-three U-boats lost in May 1943 alone. More than a thousand trained submariners dead. An entire strategy—unrestricted submarine warfare against Allied shipping—proved unsustainable.

Historians called that month Black May for the U-boat arm.

Inside those summaries lay stories like Müller’s: men whose last ninety seconds on their boat marked the moment when a weapon and a doctrine crossed a line from viable to obsolete.

In later years, Allied reports would tally Hedgehog’s accomplishments. About forty-seven U-boats destroyed by that forward-throwing mortar during the war. Forty-seven boats whose crews learned, too late, that the threat no longer came only from what they could see or hear in the old ways.

The weapon itself, the stubby projectors angled outward on an escort’s bow, would eventually rust in museums or be scrapped.

But the idea it embodied lived on.

Attack without losing contact.

Strike based on continuous information, not on guesswork.

Integrate sensors and weapons into a system where each made the other stronger.

For Bernhard Müller, that idea had a deeply personal name:

It was the force that tore his boat open in the North Atlantic and dragged his crew into the freezing sea.

But it also had a more abstract name.

It was the future.

He had been standing in the conning tower of U-672 on a calm, gray day, believing his experience and courage could carry him through one more patrol.

He had listened to strange splashes, ordered a dive, waited out a passing escort, and surfaced into darkness with every intention of doing what he had always done: hunt.

Ninety-four seconds later, his war was over.

The Hedgehog, the little spiked bombs that fell around his boat, were the immediate cause.

The real cause was a system of technology and doctrine that rendered his skill set outdated in an instant.

German command would take weeks, months, and ultimately years to fully admit that.

Müller understood it the moment a British captain wrapped him in a blanket and explained, in careful German, that the rules of the game had changed.

The last thing he saw from the conning tower was a circle of stars above a black sea and a pattern of splashes that made no sense until it was too late.

The last thing he heard from his steel command was the rush of water and the screams of men he would never see again.

Those ninety seconds were his personal ending.

They were also, in a larger sense, the end of an era when a submarine commander could believe that courage, cunning, and a low silhouette were enough to rule the night.

From then on, the ocean belonged to the side whose invisible equations were better.

News

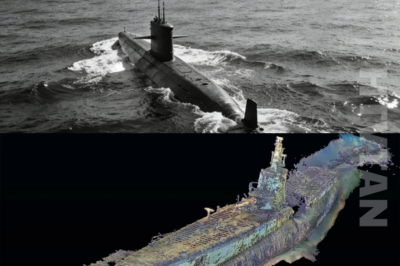

CH2. Why One U.S. Submarine Sank 7 Carriers in 6 Months — Japan Was Speechless

Why One U.S. Submarine Sank 7 Carriers in 6 Months — Japan Was Speechless The Pacific in early 1944 didn’t…

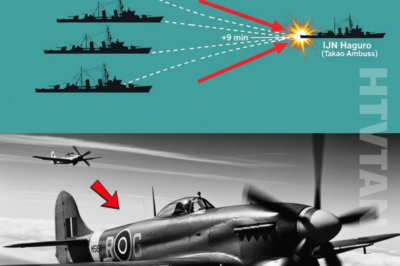

CH2. The 9 Minutes Haguro Never Got Back — When One Missed Warning Triggered the Entire Ambush

The 9 Minutes Haguro Never Got Back — When One Missed Warning Triggered the Entire Ambush It starts with a…

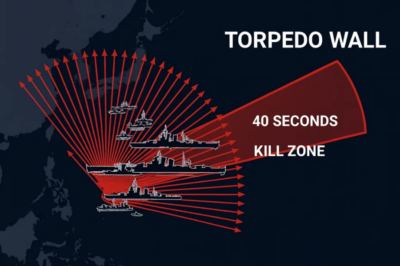

CH2. The 40-Second Torpedo Wall — How 22 Shots Erased Japan’s Night-Fighting Advantage

The 40-Second Torpedo Wall — How 22 Shots Erased Japan’s Night-Fighting Advantage The date was August 6th, 1943. The place:…

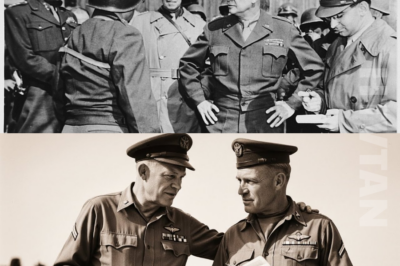

CH2. What Eisenhower Said To His Staff When Patton Crossed the Rhine Without Orders!

What Eisenhower Said To His Staff When Patton Crossed the Rhine Without Orders! March 22nd, 1945, was supposed to be…

CH2. Why Japanese Admirals Stopped Underestimating American Sailors After Midway

Why Japanese Admirals Stopped Underestimating American Sailors After Midway Commander Joseph Rochefort had forgotten what it felt like to be…

CH2. How One Sniper’s “STUPID” Mirror Trick Outsmarted the Germans Snipers

How One Sniper’s “STUPID” Mirror Trick Outsmarted the German Snipers November 3, 1944 Metz, France The wind off the Moselle…

End of content

No more pages to load