“Don’t Ever Come Back Here,” My Parents Said. I Left That Night, Snow Falling Around Me. And Later..

Part I — The Door That Closed Like a Sentence

The night my mother told me not to come back, the porch light flickered as if it, too, were deciding whether to keep me. Snow turned the street into a hush. I remember the smell of cloves from the simmering pot on the stove, the decent roast my father had carved with machine precision, the way the house glowed warm as an advertisement. I remember, with a clarity that runs like an electric line through my life, that I didn’t beg.

“Don’t ever come back here,” my mother said, one hand on the frame as if she could hold the whole house up with posture. “If you walk out with him, you are no longer our problem.”

My father stood behind her, tie still perfect at the knot, eyes fixed not on me but on the snow beyond, as if watching the weather were the same as weathering it. My sister—two years older, the prototype that made my parents believe in blueprints—hovered in the hallway and said nothing.

I stepped backward into the cold. Snowflakes stuck to my eyelashes and made the world blink slowly. My boyfriend Noah waited at the curb in a car that rattled earnestly. He looked at my empty hands and understood: no suitcase, no last-minute compromises. We drove away past the house with the swinging wooden reindeer and the one with the inflatable Santa listing toward the hydrangeas. At the light, I looked back once. The porch light steadied, then went out.

I had been a quiet child in a home where silence was the only safe accent. My mother treated reputation like religion; my father measured love in compliant minutes. Our home had rules like labels: shoes at forty-five degrees beside the door, elbows off the table, facts offered in tone and tested for discipline. My sister, Clara, performed those rules back so beautifully that applause was implied. At dinners, guests asked about her internships, her fiancé’s fellowship, her future. Then someone would turn to me, realize I was still at the table, and ask how the weather was.

The first time I brought Noah home, he borrowed a tie and called my father “sir” without irony. He showed up with a good bottle of wine and a nervous joke about showing up with a good bottle of wine. He took off his boots at the door without being asked, because he was the sort of person who noticed floors needed kindness. My mother shook his hand like an audition. My father offered a glass he did not pour.

“What do you do?” my father asked.

“I run a snowplow route in winter,” Noah said. “Foreman for a landscape company spring through fall. We put in native gardens, food forests. I’m studying for my arborist certification.”

“Trees,” my mother repeated, as if the word would melt if she held it too long. “How nice.”

After Noah forgot to call my father “sir” the third time, the temperature of the house shifted. The evening broke on a sentence. When we stood, when we reached for our coats, my mother pointed at the door with her chin and swung it open with a flourish that said she expected applause.

We spent the first months in a one-room apartment over a laundromat that steamed our winter clothes with a softness money couldn’t buy. We took turns using the good mug. We ate soup from a pot that insisted it was for six. We were not free of my parents so much as we were free around them. I worked the morning shift at a bakery where the yeast taught me patience and the regulars taught me names. Noah left at 3 a.m. for the plows when it snowed, then came home with hands that smelled like iron and ice. On days when my mother’s voice took up the entire phone, I walked to the park and watched the river push itself forward as if it were purpose with edges.

The first job I loved came with a lockbox. I started as a night-shift bookkeeper at a community clinic—stack of receipts, a ledger like a slow river, a coffee maker older than my adulthood. The clinic’s director, a woman named Mrs. Kinsey whose hair refused to obey just as persistently as her budgets did, noticed the way I wrote notes in the margins of receipts. “You’re good at seeing where the money went and where it should go,” she said. “You ever think of school?”

I had thought about school. I had thought about it in abstract nouns: obligations, expectations, tuition. But the clinic needed more than thought. I enrolled at community college, three classes at a time. At night I balanced cash drawers, in the morning I balanced equations and the fact that a life can be both precarious and triumphant.

My parents did not call. My sister sent pictures through a friend of a friend: engagement party tables with centerpieces built like arguments, a ring that would pay for a semester, a trip to Italy where the gelato looked like apology. I tried not to hate her or them for how easily they believed in pictures.

Noah saved for a truck with a plow that belonged to him. He bought it in cash and hugged the hood like it had a heartbeat. He planted berry canes in five-gallon buckets on our fire escape. We made jam on a hot plate. We gave jars to the clinic staff and the people whose names I learned at two a.m. in the waiting room: Miss Ruth with the good hat, Mr. Alvarez who shook before he laughed, a girl who wrote her name on the sign-in sheet as if the letters had to be coaxed.

We fought like people who wanted to stay. We loved like people who knew loving was sometimes this blunt: do the dishes, fix the thing, don’t make a promise sound like a plan.

Two years in, without fanfare, I moved from the clinic to a small nonprofit that helped women find housing after the nights no one sees. I wrote budgets that made rent appear out of line items and begged lenders with a polite ferocity I did not know I had. “You are unreasonable,” one of them said after I asked for a rate that belonged to a different century. “I am correct,” I said.

We moved to a one-bedroom where the windows faced a tree. Noah became a foreman. He studied at night with books that taught him the Latin names for the lives he could name in his sleep. We learned the difference between hope and denial. When my parents’ name appeared on my screen, I did not answer. When my sister wrote that she was pregnant, I sent a sweater I had knitted on a bus that smelled like strangers. She replied with a thumbs up. It was progress the size of a needle’s eye.

Five winters after the porch light went dark, Mrs. Kinsey called and used a tone that meant she was offering me something more than a job. “The Moore Family Foundation,” she said, making the name feel like a dare, “is making a gift. They’re hosting a dinner. They asked for the person who knows what the clinic will do with the money to speak.”

I laughed like a person who discovers the constraints of the camera are the same as the constraints of a mirror. “They’re who?”

“Your parents,” she said gently. “Do you want this, Laurel?”

My name had changed for some people. It had not changed for me.

“Yes,” I said. “I want to say the sentence I have earned.”

Part II — The Room Where They Kept The Silver

The ballroom downtown looked like a painting hung too low. The ice in the glasses did the polite clinking my mother trained it to do. The chandeliers pretended stars. The air smelled like money hiding from work. There were name tags like labels that said who belonged. Mine said the clinic’s name and my position. My last name sat beneath in font that made it seem neutral. When I pinned it on, it burned cold.

My mother stood near the dais in a dress that looked like a midnight with an agenda. Her hair had been convinced to behave. A diamond that you could measure irrigation projects by sat at her throat. She laughed at a man whose joke arrived already tired. My father hovered in a tuxedo that looked like it had opinions about small talk. He examined table settings as if he could infer battle plans from napkins.

They saw me precisely when they could not avoid me. My mother’s eyes widened. My father’s mouth set.

I found Mrs. Kinsey’s table. When she touched my hand, the night aligned by half an inch. “You will be fine,” she said. “You are here because they need your math.”

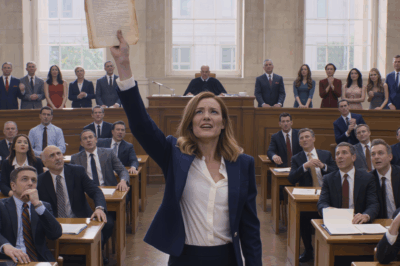

The MC used a voice that had seen too many microphones. “Tonight’s host,” she said, “is the Moore Family Foundation.” Applause that sounded like obligation. “Later, we will hear from the clinic’s representative, Ms. Laurel Bennett.”

I tasted my maiden name like a fruit I wasn’t allowed to touch. It had never belonged to me. It belonged to a map I no longer carried.

Dinner arrived. The salmon was good but bored with itself. I ate because you cannot stand up steady on principle alone. I watched my sister across the room, her hand on a toddler’s hair, her husband at her elbow. She looked lovely and tired, a pairing that never learned to dislike each other. She saw me and smiled a smile constructed from something like regret. It missed the corners.

When the MC called my name, the room did that thing rooms do: it pretended it had been waiting to listen. I stood and walked to the stage, every footstep measured—bus rides, two jobs, a man with rough hands and a soft heart, the clinic at three a.m. when the lobby slept like a crowded prayer. I did not look at my parents until I reached the microphone. Then I looked right at them.

“Thank you for this gift,” I said. “Our clinic will use it to keep lights on, doors open, and the kind of promises you cannot put on a brochure.”

A few polite laughs. People whose jobs require them to laugh at the right places.

“When I first came to the clinic,” I continued, “I learned two things. One: emergencies do not care about your calendar. Two: the difference between a house and a home is sometimes a person waiting with the door open.”

Something shifted in the ceiling—the sound that rooms make when they decide not to betray you.

“I grew up thinking that belonging was a performance you could practice into perfection,” I said. “Then I learned that love, if it needs obedience more than help, is a contract, not a heart.”

My mother flinched and pretended it was the lighting.

“We will use this money to pay for things that look small but hold everything: a month of rent averaged across six women, a bus pass between interviews, a locksmith when a man we do not invite refuses to leave. We will use it with the precision that comes from knowing waste is a form of harm.”

Nobody clapped. They listened. In their listening, a tiny apology formed—for the rooms we had all sat in while pretending not to hear the loudest thing in them.

“Generosity is not absolution,” I said finally, and felt the edge of my own voice. “But it is a start.”

I handed the oversized check to the MC. She smiled for the camera like she had been practicing all her life. I stepped down. My heart did not pound. It kept time.

My mother reached me near the table with the coffee. “Laurel,” she said, her voice a small reprimand in silk. “You could have told us you would be here.”

“You could have told me I would be allowed to come back,” I said.

“We were scared,” she said, and she meant it. “We wanted the best for you.”

“You wanted me in a story where I made you comfortable,” I said. “I am not good at that story.”

My father’s voice arrived like a courtesy. “You did well,” he said. He sounded like a man grading a drill.

“I did my job,” I said. “I am good at that.”

My sister hovered, grief tucked into the corner of her mouth until it made a dimple. “We missed you,” she said. “He misses you.”

“What you miss,” I said, “is the version of me that did not ask you to miss me in any real way.”

It was not cruelty. It was a description my therapist would call “present-tense observation.”

They stood in their golden room, the chandeliers pretending stars, the tablecloths ironed into obedience. I stood in mine, which had nothing to do with linens.

Noah waited near the coat check. A man we did not know handed me a claim ticket with the gentleness of someone who has found a wallet and intends to return it. “You were the only person who talked about receipts,” he said. “Thank you.”

“Numbers tell stories,” I said. “I’m just the translator.”

On the way out, my mother said my name again. She was not the woman who’d said don’t ever come back. She was the woman who had to live with that sentence. I could not help her carry it without picking it up.

Outside, the rain had given up, and the city had that washed look it wears most beautifully. Noah slid the good coat over my shoulders. We walked to the car past a couple arguing gently about whether to use the parking validation. We didn’t speak. It was our best language.

Part III — The Long Winter And The Work of Thaw

If the story ended there—in a ballroom with chandeliers and practiced smiles—it would be a parable, not a life. But life is long and ordinary between declarations.

I went to work. At the clinic I built a budget the mayor complimented by email and then ignored publicly. We kept the lights on anyway. I trained a girl with a GED and a mind that turned ledgers obedient in a week. When she passed her first exam, she cried into a napkin in the supply closet like it was a sacrament. I restocked the napkin box and found my own eyes behaving badly.

Noah’s company landed a city contract to install native gardens in three parks on the south side. He kissed me with dirt on his cheek that tasted like loving a place enough to put something back. He passed his arborist exam and bought me a cake with a tree piped on it. The bakery spelled arborist wrong. We ate it anyway.

My father came to the clinic once. He walked in like bad news in a suit, hands clasped, eyes scanning for an exit that would allow him to pretend he hadn’t meant to come. He sat in the chair by my desk like a man who had come to talk about anything else.

“I was wrong,” he said finally. The words scratched his throat coming out. “I thought strength was… a posture.”

“Strength is sometimes a person who remembers names,” I said, “and sometimes it is a person who leaves.”

He nodded. His neck lost an inch. “Your mother is not well,” he said, and I felt the old house tilt beneath my feet. “Not—the kind of thing—” He stopped. He had never learned the grammar of grief, only its drills.

“What do you need?” I said. He flinched, unused to help that arrived without a lecture. “Not money,” I added. “Tell me how to make it easier.”

He told me a list I wrote down in a hand that had learned to carry other people’s days. Groceries on Tuesdays, rides to the appointment that demanded he pretend he wasn’t wearing a coat. Sit with her when she woke from a nap and thought the house was a train station. Answer the phone when nothing changed but somebody needed to hear you listening.

I did those things. I did not move back in. I did not use the word home for a place that had thrown me out. I showed up with soup and early-morning coffee and an ability to speak to nurses without screaming. My mother’s hair softened on the pillow. Her hands forgot things and then found them. Once, she said my name like she was telling herself a story from the beginning.

“I should have—” she began.

“You didn’t,” I said. “Here we are.”

She laughed, a single breath of air that forgave neither of us and also forgave everything. “You don’t look cold anymore,” she said.

“I’m not,” I said.

Clara brought the baby and looked at me as if I had become a continent she hadn’t mapped. We bickered about stupid things and used the arguments like thread. When the baby grabbed my nose and cackled with the delight of a creature discovering both cause and effect, my mother cried the way the inside of a shell sounds.

After the worst day, when my mother didn’t wake up again, the house smelled like starch and citrus and the metallic sweetness that lingers after tears. The porch light stayed on for an entire week. On the morning of the service, my father asked if I would speak. “I didn’t plan,” he said, apologetic to the air. “I always thought I would know what to say.”

“I am going to talk about her roast chicken like it was a revolution,” I said. “I am going to say she taught me that weather is a thing we see together.”

He smiled without showing teeth. “That sounds right.”

I drove to the clinic after the reception because being in that building makes my emotions line up into facts. I wrote thank-you notes to donors who could not afford their generosity and to those who could not afford to be stingy and said it anyway. I approved a new security camera for the back entrance. I cried for exactly ten minutes in the supply closet and then stapled a packet that needed to be mailed by five.

In the spring, a letter arrived from a law firm with a name that serial numbers its partners. My parents’ foundation wanted to begin a capacity-building pilot program: a pool of money meant to strengthen the unglamorous parts of small organizations. The clinic applied. We were awarded a grant. My signature on the acceptance letter sat beside my father’s on the check. We did not make eye contact through paper.

Summer brought heat and the kind of thunderstorms that make the city remember it’s built on stories. Noah and I spent a week in a cabin where the Wi-Fi did not remember us. He built a shelf. I read a book that made me cry, then laugh, then call Mrs. Kinsey and tell her we had to try writing a curriculum for non-profit directors on how not to set themselves on fire while trying to extinguish ten others. She said yes before I finished the sentence.

Autumn returned in a coat that made the map look brave. I began teaching Thursday nights: Budgeting for the Brave, which is a joke because bravery is required even to put the word budget on a flyer. I told stories about receipts that saved lives and one that saved a dog. The woman in the front row with the neck tattoo took notes like she expected the exam to shuffle itself and find her sleep. She passed anyway.

A year after the ballroom, the Foundation invited me to sit on its advisory board. I accepted carefully. I do not trust rooms that applaud themselves. But sometimes it is your job not to refuse a chair simply because it once belonged to someone who tried to seat you elsewhere. At my first meeting, my father said, “Welcome,” and I said, “I’ll be insufferable,” and he said, “Good.”

I hung my mother’s compass on a tiny nail in the frame of my office door. It does not point true indoors, but it matters where you keep instruments. It’s my reminder that catching north is sometimes less about magnets than about being willing to put your finger down and say, here.

Part IV — The End That Needed Saying

Five winters after the porch light went out, after the ballroom, after the clinic’s fiscal year closed in the black by three dollars and nine cents, my father stood in my doorway holding a stack of papers and a pie he had baked with a recipe he read from his phone.

“It is not good,” he said, and he was correct.

He gave me the papers like a person returning a library book ten years late. “We are rewriting the bylaws,” he said. “We thought you might—”

I read quickly. The Foundation would formalize a practice we had already been nudging it into: unrestricted funding beyond the polite percentage, grants that paid for paper and salaries and locks. A commitment to board seats for those who had once sat in clinic waiting rooms at midnight and thus knew how to ask different questions.

It was, in short, the thing my mother believed in and my father had learned the hard way. It was leaving the porch light on.

“This is good,” I said. “You did this because you want to be different.”

“I did it because numbers made it obvious,” he said, and we both laughed because that is our love language: admit you are emotional only via a spreadsheet.

We took the pie to Noah’s crew, who ate it without complaint because a fork is a formality when kindness is the food. My father watched Noah talk about a tree with the kind of attentiveness that looks like respect, and I watched my father do it, and for a moment my life fit like weather—unpredictable and also exactly what you would have forecast if you had paid attention to the clouds.

The finale did not come with a soundtrack. It came with a quiet I had built by hand.

On the anniversary of the night my mother closed the door, I walked to my old street. Snow fell like confession. The porch light on that house burned steady. Clara’s kid built a fort that had no idea it would be remembered. I stood across the street and thanked winter for not being sentimental. Then I walked to the park and watched the river push its edges forward because that is what it knows how to do.

When I got home, my phone chimed. A text from Clara: We’re making soup. Come over?

I answered: Tomorrow. I have clinic tonight. Come by for coffee at seven. Bring the kid’s mittens.

There it was—the thing I had wanted from the first chapter and finally knew how to get in the last: not apologies, not credit, not a revised role in someone else’s script. A sentence with no exclamation point that still said love.

We ate soup that tasted like herbs planted on a fire escape years ago. After, I pulled out a box and Ruby—Clara’s daughter—chose a hat with a ridiculous pompom. Noah changed the lightbulb in the stairwell without being asked. My father put his napkin on his lap carefully. When he reached for the salt, he said, “Please.” Progress comes with politeness sometimes; sometimes it does not ask your permission to be remarkable.

Before bed, I opened my notebook and made a list.

-

Call the clinic’s donor who loves to be thanked in handwriting.

Approve the revised HVAC contract.

Buy better mittens for Ruby.

Email the Foundation: yes, unrestricted. Yes, multi-year. Yes, trusts as tools, not trophies.

Put the compass where I will see it in the morning.

I turned out the light. Snow fell, as if trying to erase and also trying to write. I thought about the car idling outside five winters earlier, the door I had shut, the sentence my mother had said and my life had turned into an instrument. I thought about all the people who would arrive at doors in the next storm and need someone to stand there and say, get in.

The porch light across the street shone through the dark like an answer someone finally learned how to give. I fell asleep not cold.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Dad and “Deadbeat” Brother Sold My Home While I Was in Okinawa — But That House Really Was…

While I was serving in Okinawa with the Marine Corps, I thought my home back in the States was the…

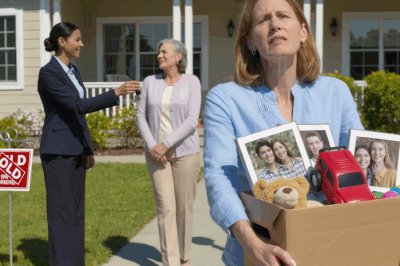

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash Part 1 The scent of lilies and…

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court…

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It Part 1 The email hit my inbox like…

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”?

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”? Part 1 The email wasn’t even addressed to me. It arrived…

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last Part 1 The…

End of content

No more pages to load