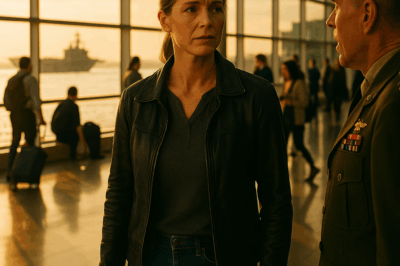

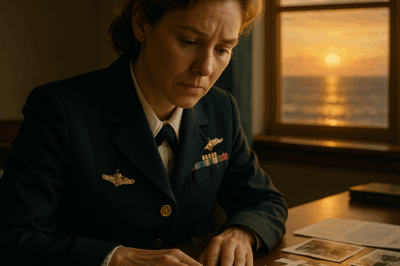

He called me a disgrace — right there in front of the judge. My father tore the envelope open, ready to prove that I was nothing. But what he found inside… was the truth he’d spent twenty years running from. That day in court wasn’t about money. It was about dignity, legacy, and what it really means to be family. He tried to bury my name. But the letter in his hands revealed who I had become — Admiral Morgan, U.S. Navy SEAL Command.

Part I — The Envelope

He ripped the envelope open so hard the seal screamed. The flap tore with that small, unforgiving sound paper makes when it’s had enough. A glossy square slid free, turned once in the thin air, and landed at the edge of the counsel table like a playing card that didn’t understand how much had been bet on it. For half a second, the whole room held its breath. Then my father found his voice.

“No.”

It came out raw, longer than one syllable deserves, and too honest for a man who’d spent thirty years polishing his sentences until they shone and said nothing true.

Outside, rain didn’t fall so much as drill. It threw itself sideways against the courthouse glass, needling the panes into a gray hum. I had walked in through it without an umbrella. The uniform teaches you that weather is mostly detail if you know where you’re headed. My dress whites held their line, habit stitched into every seam, starch turned spine.

The clerk read the caption. The estate of Margaret Ellis Morgan. My mother, who had smoothed bandages onto skinned knees and quieted nightmares with the same firm hand she used to keep a kitchen running. She had written to me just before the end, a letter Grace Whitmore—our neighbor-turned-lawyer—now held. Grace had shown it to me in my mother’s kitchen two nights ago, the lamplight making my mother’s handwriting look steadier than the breath that had made it.

“She was very clear,” Grace had said, tapping the envelope. “Read into the record, before anything else.”

My father stood at counsel table, the way men stand when they are sure the room is a stage they built. He wore a new suit and the old posture, jaw set, fingers resting lightly on the wood like he could steady the furniture by willing it. Linda, his second wife, floated at his elbow, her mouth a ribbon cutter and a razor. He didn’t look at me. That was part of the act. Don’t see her, and maybe the town won’t either.

“On the matter of the last will and testament of Mrs. Morgan,” the judge said. His voice was kind and unsentimental, the tone of people who have sat in judgment long enough to learn that wrath is inefficient.

Grace rose. She introduced the will with the muscle-memory phrases. Sound mind. Revoking prior instruments. She slid the cream envelope forward. My mother’s hand had spelled my name on it as if it were a blessing. That alone almost unspooled me. I set my palms on my knees, thumbs flat, the way you do to keep a map steady in wind.

“Let’s not delay the inevitable,” my father said, smiling the way a man smiles when he thinks a jury likes him for his ring and his first name. “We all know what Margaret wanted.”

“Mr. Morgan,” the judge said gently, which in bench-speak means we will do this by the book if it kills you.

Grace picked up the envelope. Before she could break the seal, my father reached. He didn’t ask. He didn’t wait. He took.

Linda leaned and whispered, “Objection,” because some people believe using a courtroom word conjures a courtroom power. It doesn’t. The judge lifted an eyebrow that said, Your opponent is the dead and the law. Pick a better fight.

The paper rasped under my father’s nail. He turned the envelope like a small engine looking for a spark. He tore.

The photograph slid out.

He stared down at it as if it should have jumped to align with his story. He squinted, then leaned forward. The wedding band he wore flashed. The muscles at the hinge of his jaw worked. He looked at me—fast, involuntary—and away, like the picture had pushed back through the glossy into something he didn’t want to admit he knew.

“Anyone can rent a uniform,” he tried.

“Mr. Morgan,” the judge said, more steel now.

Grace touched the corner of the photograph, angling it toward the bench, then toward the clerk. She didn’t parade it. She let it exist in a room where denial had been the only thing allowed to take up space.

The clerk cleared her throat and read the cover identification aloud, careful, unhurried.

“Subject: Morgan, Elise. Rank: Rear Admiral (Lower Half). Assignment: Naval Special Warfare Command.”

Rain softened against the windows, like even the storm had decided to sit and listen.

“Proceed,” the judge said.

Grace lifted the letter. It made a small sound coming free—a sigh of paper, the way receipts sigh when they are finally asked to become evidence.

“My dearest Elise,” she read, and my mother’s voice collapsed twenty years into one instant. “If this is being read, I am where I can hear the gulls without getting cold. I am wearing the shawl you teased me about. I am thinking of your hands and the way you set a cup down without noise. You learned that in a house where loud was mistaken for strong.”

The words moved forward like tide. They didn’t look to see who agreed. They didn’t check if the room was ready.

“Before we make a ledger of things,” Grace continued, “we must make a ledger of truths. Your father chose performance over honesty, control over care. I tried to love him into a better choice. Love alone could not do that work.”

Linda’s smile tightened until it was geometry. My father’s breath shifted the way a runner’s does when a hill reveals itself.

“Elise,” the letter said, “I was proud when you were six and read the names on the memorial without skipping the hard ones. I was proud when you were twelve and showed up to shovel Mrs. Olsen’s steps before anyone else. I was proud when you were eighteen and chose a road I feared because you believed you could do some good. I did not say these things often enough. I am saying them now, out loud, with the law listening.”

I breathed my four counts. In. Hold. Out. Hold.

“As to the estate,” she wrote. “The house on Marsh Road, the savings, the retirement, these to be distributed as attached. But there is also the matter of recognition. I have asked that a photograph be attached to this letter and that the court take notice of who my daughter is, not just who she was.”

My father turned the photo again with two fingers, as if it might rearrange itself into something safer if he pushed hard enough. The picture did not move. Two silver stars at my shoulders. White clean. Captions a life cannot fake.

“Richard,” my mother’s voice came through the paper, gentler than he deserves, “if you are in this room, listen without arguing. Your anger is not a fact. It is a habit. If you have never managed to say ‘I am sorry’ to our daughter, let the court’s hearing be where you learn another sentence: ‘I was wrong.’”

He flinched, and a sound like a held breath escaped him. He covered it with a scoff that tripped on its own shoes.

“For the ledger,” she finished, “I leave what I have to the child who kept honor when none was offered—to Elise. If she declines, let the rest go to Willow Creek Literacy, the library that kept me safe when noise pretended to be love. Richard, I leave you the portrait of your father. Hang it where you will see it when you talk about legacy. Let it remind you legacy is not permission. It is responsibility.”

Grace put the letter down. She did not look at me. She did not need to.

“Allocations as attached,” the judge said.

“House and accounts to Elise,” Grace said. “Personal journals to Elise. Portrait of Mr. Morgan’s father to Richard. Contingency to Willow Creek Literacy should Elise decline.”

“I’ll contest,” my father said quickly, like a man knocking on a door as it closed. “Undue influence.”

“Medical clearance attached,” Grace said. “Two witnesses. Notarized. Execution six weeks prior. On what grounds, your honor?”

“None I’ve heard,” the judge said. He kept his pen.

I stood. The coat tugged clean at my shoulders. “Your honor,” I said, voice steady in the way you learn to make it steady when wind means trouble, not weather. “I accept the journals and personal effects. I decline the rest.”

Even the lights seemed to sharpen. Someone in the back row coughed into a fist and missed. Linda’s chin jerked. My father looked up, anger and relief and pride passing like weather across his face, none staying long enough to be named.

“You’re grandstanding,” he said. “You want the town to see a saint.”

“No,” I said. “I want lamps for girls who need one. She asked for that.”

“So reflected,” the judge said softly. “Residue to Willow Creek Literacy.”

The clerk’s keys clicked. The rain stopped.

Part II — The House Where Loud Was Strong

The first time my father called me a disgrace, I was eighteen and wearing a thrift-store skirt to pretend an occasion was more important than it felt. The porch light was on, and June had spread itself over the yard like hot chalk. He didn’t say “stay.” He didn’t say “don’t go.” He stood with his arms crossed and said, “A Morgan doesn’t crawl in mud.” He pronounced Marines like I’d misspelled a word in a family letter.

He didn’t slam the door. He made that soft hush doors make when they have done this before. My mother stood at the sink, hands on the edge, wrists white, staring at nothing. I texted my brother—two years older, golden—goodbye. He sent back a muscle emoji and a beer.

At Annapolis, I learned to run until my body took instruction from something better than habit. I learned to turn panic into math. In through the nose for four, hold for four, out through the mouth for four, hold for four. I learned that the world does not shrink for you; you move through it larger. In Haiti after the earthquake, I drew a grid with chalk on a church pew, and a supply chain obeyed it enough to feed people.

In a tent under a corrugated roof in Afghanistan, I wrote a letter and sent it home. It came back unopened. Don’t waste postage, someone else had scrawled across my name. I carried that note in a cargo pocket for six months until sweat made the ink into a bruise I stopped needing. In Norfolk, a cook made me a birthday cake with my rank misspelled. I ate it and taught a twenty-year-old how to fold a flag without letting it touch the deck.

When the orders came to Naval Special Warfare Command, I thought of my mother’s compass. It always points true, she had whispered, even when people don’t. My father’s voice—You’ll wash out—followed me into midnight racks and morning briefings. It softened when my people began to trust me the only way trust matters: with their lives.

Part III — The Portrait and the Plank

Court adjourned with a sigh rather than a bang. People filtered out the way a congregation does when the sermon has been better than the hymn—quieter, with more to do. Mrs. Olsen touched my sleeve in the aisle. “We knew,” she whispered, her breath spearmint and mercy. “Not the stars. The steadiness.” I squeezed her hand.

In the lobby, my father stood with the claim ticket for his father’s portrait like a man still playing a part whose script had been changed mid-scene. He looked at me only when he had arranged his face into the safety of an old shape.

“You think this erases twenty years,” he said.

“No,” I said. “It puts them where they belong.”

“You declined her money.”

“She didn’t leave me money. She left me time.” I glanced at the letter. “I’m giving most of it away.”

“Magnanimous,” Linda said.

“Remedial,” I said.

At the steps, the deputy held the door. “Commander,” he said, using the wrong title on purpose to be kind. I nodded. I am not that rank anymore. I carry what it taught me anyway.

Outside, the air smelled like wet iron. The flag hung heavy. My father came out and stopped in the drizzle, hatless, a man who had finally let the weather touch him.

“Elise,” he said.

“Dad.”

He swallowed. He said three words I didn’t beg him for. “I was wrong.”

They didn’t rebuild a house. They laid a plank across a gap. You can cross a plank if you’re careful.

“All right,” I said. Not forgiveness as theater. Forgiveness as future tense.

He wiped his cheek and blamed the rain. He looked at my mother’s name on the letter. He looked at the portrait claim ticket in his hand. He looked at me. None of these looks were the same as the ones he had practiced for years.

“What do I do now?” he asked.

“Go to the library,” I said. “Write a check. Show up on Tuesday nights and shelve books. Learn the names of kids who come because the house is loud. Let legacy be a verb.”

He nodded. It looked strange on him, and new, and not impossible.

Part IV — Lamps

I drove to the coastal cemetery after. The cedar tree leaned east as if it had survived one too many storms and decided not to pretend anymore. Sun pushed through cloud ragged, honest. I set my palm against my mother’s stone. The journals in my other arm smelled like wool and lemon oil and stew. I set them down. The metal she’d liked—“the weight of that one looks honest”—I placed at the base for a minute and then took back, because you don’t leave honesty out for the weather to take.

“Hey, Mom,” I said. If any sentence would bring a ghost back, it would be that one. She didn’t, because she wouldn’t. She trusted me in life; she trusted me after. I told her what I’d done with her letter. I told her about the teenager in the varsity jacket whispering “She’s the one,” and the deputy sliding a door open like respect. I told her about Willow Creek Literacy, and the Tuesday nights when lamps would be turned on and girls would pull three books and a life out of a shelf that had been organized by a man trying to learn a better language.

When I turned to go, footsteps came up the gravel—halting at first, then committed. My father stopped at the edge of the grass, hat in his hand. He didn’t speak until he had done the second hard thing of the day: let the salt in the air find his eyes and not cover it with a lie.

“Shame kept me small,” he said.

“It was never a good tailor,” I said.

He breathed. He put two fingers to the top of the stone, an old salute reduced to touch. “Thank you,” he told her name. He meant more than a distribution. He meant the letter, the lamps, the plank.

“I brought nothing,” he added.

“You brought yourself,” I said. “It’s a start.”

He went to the library that Tuesday. Not to be seen. To learn the alphabet again.

Part V — The Record

Months later, the veterans’ center asked me to speak over coffee and sheet cake. The director introduced me without embroidery. I stood at the lectern and told a room of men and women who knew more about endings than beginnings that my mother had written a letter and a town had read it aloud.

“We called control care,” I said. “We called quiet weak. We called legacy permission. We were wrong.”

Heads nodded. A corman in the second row said “Amen,” like he meant it.

I told them about the library lamps and the man labeling spines who’d gone his whole life filing people by how they made him feel. I told them about a teenager who asked where the biographies were, and how a man said “Pick two and come back next week,” and how that is legacy, not the portrait over a mantle.

Afterward, the director thanked me at the door. “He came,” he said, nodding toward the back row, now empty but for a hat left on a chair. “He left before the sheet cake, but he was here.”

Showing up is a kind of sentence, too.

Back at base, someone asked what it felt like when the clerk read my rank in that courtroom. I told them it felt like breath. Not because of pride. Because it proved the record is patient. It waits until you need it, and then it says what it has always said. It doesn’t need approval. It needs air.

That day in court wasn’t about money. It was about a ledger that couldn’t fit in a checkbook. Dignity, which is work. Legacy, which is verb. Family, which is what people do when no one is looking. My father tried to bury my name under a porch light twenty years ago. He tried to rewrite me in a toast to a town that clapped on cue. But the letter in his hands in the judge’s eye and the rain’s steady percussion revealed who I had become: Admiral Morgan. U.S. Navy. Naval Special Warfare Command.

He tore the envelope like he could keep the truth out longer. He learned that day what I had learned in worse rooms. Some walls are fences men build. Some walls are waves that have decided to stop pretending they won’t come in.

If you ever find yourself in a small room with a big silence and a letter in someone’s hands, breathe. The truth doesn’t need your panic. It needs your steadiness. Put your palms on your knees. Count your four. Let the record say what it knows. Decline what you don’t need. Turn on a lamp for someone who does.

And if a man who once called you a disgrace says “I was wrong,” don’t turn it into a parade. Put it where it belongs: the first plank of a bridge someone else will need to cross after you’ve gone back to the work.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I Was Mistaken for a Civilian — Until the Colonel Said, ‘Ma’am… the Black Widow of SEAL?’

At the airport, she was just another woman in jeans—until one quiet word froze the entire lounge. No medals. No…

CH2. I Thought It Was Just a Family Party, Until My SEAL Said, “This Isn’t a Birthday… It’s a Setup.”

It was supposed to be just a family party — laughter, candles, and a few harmless speeches. But halfway through…

CH2. I Thought My Father Died in 1991 — Until I Saw His Signature in the Navy Record…

They told me my father died in 1991 — a Navy officer lost in a mission no one would talk…

CH2. At My Commissioning, Stepfather Pulled a Gun—Bleeding, The General Beside Me Exploded in Fury.

At My Commissioning, Stepfather Pulled a Gun—Bleeding, The General Beside Me Exploded in Fury. Part I — The Shot…

CH2. My Father, An Admiral, Secretly Gave My Promotion To His New Wife’s Daughter — BUT HONOR NEVER LIES

He took my promotion and handed it to his new wife’s daughter — the one who’d never worn mud, sweat,…

CH2. My Father Mocked Me in Front of 500 Guests — Until the Bride Said: “Admiral… Is That You?”

At my brother’s lavish wedding, my father raised his glass and humiliated me in front of 500 guests, calling me…

End of content

No more pages to load