At My Commissioning, Stepfather Pulled a Gun—Bleeding, The General Beside Me Exploded in Fury.

Part I — The Shot That Broke the Room, Not Me

They say the loudest moments in life are sometimes the quietest inside your head. When my stepfather pulled the gun at my awards ceremony, the world froze. I didn’t hear the screams. I didn’t see the flashes. I saw only him—the man who ruined my childhood—finally revealing to the world who he truly was.

Heat tore through my left hip. My legs buckled. I refused to fall.

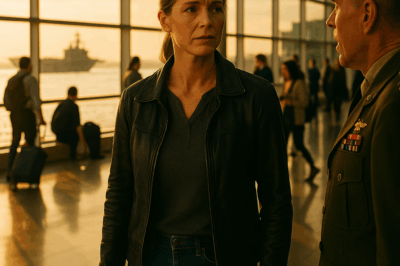

Gasps, then the kind of silence that has teeth. Security surged. Hands reached. And above them all, General Lucas Monroe—four stars, a spine like a lighthouse—stepped to my side and roared a command that rattled the chandeliers. “Drop the weapon. Now.”

Charles Grant didn’t. He grinned—older, grayer, same dead eyes—lifted the pistol toward my chest.

Another shot cracked the air, but not from him. Monroe’s detail collided with Charles in a mess of suits and cursing. Metal clattered. Hands pinned. The man who taught me fear laughed as they hauled him down the aisle.

“You think you’re free?” he spat, craning his neck to find me. “You’ll never be free until I say so.”

My knees hit the stage. Medics swarmed. The lights turned into suns. I tasted copper and ceremony polish and whispered the only oath I believed in: “You’ll regret that, Charles. I swear it.”

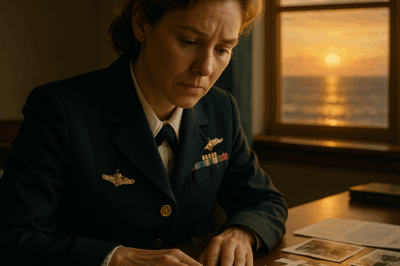

I woke three days later to the hum of military machines and the antiseptic devotion of a ward where heroes sometimes go to learn how to be human again. My hip was a furnace surrounded by ice. The bullet had shattered the outer edge of the acetabulum and splintered my plans with surgical precision. I was twenty-eight, promoted young, fresh from the Macara rescue—a hell of a river run through a jungle that hated us. I’d stood at that podium to receive the Medal of Valor, and he had put a hole in the moment big enough to walk his old power through.

General Monroe visited every day. He brought coffee that violated regulations and a voice that made rules, then broke them when kindness demanded. “He’s in federal custody,” he said, first thing. “Refusing to talk. Says he has a deal ‘upstairs.’”

Deals. Charles collected them like stamps. When I was sixteen, I’d heard him tell a friend on the phone, “Loyalty doesn’t come from love. It comes from leverage.” He wore respect like a suit he could return for store credit.

“Sir,” I said, fighting the tremor in my throat, “he won’t stop if he still thinks he owns the room.”

Monroe watched me the way the ocean watches a storm, measuring its shape. “Maya, you need time. Bone and brain both. Healing isn’t weakness.”

“I’m not healing,” I said, “until he’s gone.”

He didn’t agree. He didn’t argue. He left the coffee, left a stack of reports, and on top, a photograph from the ceremony. In it, I’m standing straight, blood shadowing the line of my trousers, jaw set, eyes locked on him. In the corner, you can see Monroe’s hand raised—not to calm a crowd, but to aim consequences.

I learned to walk twice. The first time when I was a child in a house where silence could bruise you. The second time with a crutch and a physical therapist named Marisol who believed in laughter as much as lunge squats. “You lead squads,” she said, “you can lead your leg.” The scar had a mind of its own—throbbed at weather, hummed at night, reminded me I belonged to a club that doesn’t advertise: the ones who hurt and keep going.

While I counted steps, Sergeant Ji-woo Kim—my right hand in Macara, my compass when mine shook—brought me news that smelled like smoke. “Rumors,” she said. “Someone’s greasing doors at the detention center. The kind of lubrication money can buy when it thinks it’s clever.”

I told her everything then. Not the amplified, press-release version of me. The truth. “Before my mother died, he took her savings. After, he tried to take me. When I ran, he told me no one would believe a broken girl. He’s not just a nightmare, Ji. He’s an industry.”

She nodded once, the way soldiers nod when they accept a mission that wasn’t on any briefing. “Then we expose the industry.”

At night, the hospital dimmed into a confession booth. I stared at the ceiling and replayed the Macara river—trees clawing the sky, the tin scream of the skiff, the boy I pulled by the collar from a slick of diesel and faith—and wondered how a man could be brave under incoming fire and still shake at the ghost of a front door closing. Courage comes in mismatched sizes. I learned to wear both.

Monroe’s visits kept cadence. He told me about bureaucrats—some useful, some decorative—and about a federal prosecutor whose eyes sharpened at the word “trafficking.” He sighed once, the sound any enlisted would recognize: the exhale that means the truth is bigger than a single arrest. “Whatever Charles is,” he said, “he isn’t alone.”

“Then neither am I,” I answered.

Part II — Building the Case in the Dark

We didn’t kick in doors. We opened drawers. Quietly. Patiently. The way you disarm a trap by understanding it.

Through Monroe, I got authorized limited duty—paperwork, analysis, the kind of work they give a captain with a cane and a reason. I built a task list and gave it a name only I would smile at: Operation Lantern. Let him have shadows. We’d bring light.

Ji woo recruited our bad-weather crew: Sergeant Román Alvarez—signals and sarcasm; Specialist Naomi Patel—cyber, hair in a messy knot that can hide another plan; Warrant Officer “Dutch” Hendricks—aviation, hands like rope; and Staff Sergeant Amira Saleh—logistics with a grudge against sloppy systems. We met in a borrowed ops room at dusk, the long table scarred by other people’s fights. I stood because sitting hurt worse.

“Here’s what we know,” I said, pointing to a map webbed with red string. “Charles Grant. Public face—real estate, consulting, philanthropy with very good photographers. Private face—offshore accounts, shell companies, three PO boxes in states with more cattle than people. Rumored partners: one defense contractor with a sweetheart supply line, two lobbyists with a talent for plausible deniability, and a shipping magnate who likes his boats and his secrets the same size.”

Naomi cracked knuckles over a keyboard. “Grant’s personal assistant forwarded exactly one email to a private address at 3:14 a.m., two months ago. Subject line blank. Attachment size: 7.8 megabytes. Encrypted, but the wrapper’s old. He’s arrogant.”

“Arrogant saves us work,” Ji said, and I loved her for that.

We followed money. Money is loyal to itself. It doesn’t care about family or fear. It leaves trails in exchange rates and receipts and the smug backs of limited liability companies. We traced a line from a grants foundation in Austin to a security consultancy in Warsaw to a warehouse outside Macara with crates labeled agricultural equipment that were heavy with something else. Román pulled satellite passes. Dutch called in a favor from a watch officer who owed him a Thanksgiving. Amira got manifests by asking a clerk named Lena how her cat was doing and then asking again, with sugar, for the “older copies, just to make sure the audit’s clean.”

I recorded it all. Screenshots and sworn statements and enough metadata to make a courtroom yawn until it realized it was watching a crime do its hair. Each night, the scar sang; each morning, I sang back with a new folder.

Monroe didn’t read me the riot act. He read the files. He stopped mid-page once and said, softly, as if to the document, “You picked the wrong soldier, Grant.”

“He thinks he picked the right girl,” I said. “The one he made. The one who runs.”

“And?” Monroe asked.

“I learned to stop running.”

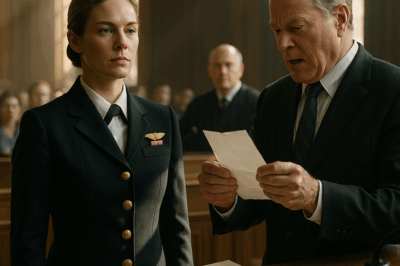

While we hunted, Charles schemed. He filed motions through lawyers with teeth like piano keys. He invoked terms that always smell like rot—due process, misunderstanding, mistaken identity—hoping they could dress a wolf and pass it off as a dog. The prosecutor—Assistant U.S. Attorney Linh Tran—called me in for a prep and left with a stack of printed proof so high it impressed the elevator. “Captain Rivers,” she said, eyes bright not with flattery but with fire, “if even a quarter of this checks, he’s not seeing sunlight again.”

“Check it all,” I told her. “He counts on people being too tired to finish.”

Three weeks before his arraignment, a rumor slipped under our door. A corrections officer cousin of a defense contractor’s nephew—ridiculous line, exactly the kind Charles used—had a girlfriend who posted a photo from a lake house with a caption that said, “Big day for Uncle C.” We ran the plates in the background of her pic. The car belonged to a lobbyist on our wall. The time stamp put them together twelve minutes after Charles fired his lawyers for “insufficient creativity.”

I requested clearance to visit the detention facility under the pretense of a victim’s impact statement. The warden, a square man hollowed out by other people’s messes, made me coffee that tasted like penance and said, “We’ve heard some noise. It’s being handled.”

“Handled by whom?” I asked.

“People who like the word interagency.” He shrugged. “You know how it is.”

“I do,” I said. “It’s why I brought my own broom.”

I didn’t go to his cell. I went to the intake desk at 0400 on a Tuesday and asked a night clerk for the trash from the visitor lockers. People dump more than gum in bins when they think doors are loud enough to cover their carelessness. In a wad of paper marked with a boutique law firm’s watermark, Naomi later found a set of six-digit codes handwritten twice—once correct, once with an error mark through the fifth number. We matched them to the control panel of a service corridor door that was never supposed to open from the outside. Someone had rehearsed.

“Three days,” Monroe said, reading Tran’s text off his phone. “Arraignment moved to Friday. We need to survive forty-eight hours.”

“Then we do what he doesn’t expect,” I said. “We tell the truth. Publicly.”

Monroe stared, then smiled like a storm choosing a direction. “You want the same hall.”

“I want the stain erased,” I said. “I want the room to learn a new story.”

Part III — The Second Stage, the Second Shot

The press release read like hope: Captain Maya Rivers to address rehabilitation and resilience; proceeds of the reception to fund a program for survivors of domestic abuse who serve. It wasn’t for him. It was for us—for anyone who learned to wear a uniform and a scar at the same time and tired of asking which one they had to hide.

Behind the scenes, our team wove netting no one could see. Amira seeded agents at doors with credentials so boring they became invisible. Dutch ran a quiet loop above the city, a helicopter you only hear if you’ve lived a life that trains you to hear rotors in your sleep. Román set up discreet RF sniffers to catch uninvited earpieces. Naomi synced the hall’s AV to a cloned drive that would play whether a saboteur said yes or no. Ji was everywhere.

I walked in with a cane that matched nothing but my honesty and took my place at a podium I didn’t owe an apology. Monroe stood beside me, enough presence to hold a building in place.

“Three months ago,” I said, “I was shot by a man who once called himself my father. He will answer for that. But there’s more to answer for.”

The screen behind me woke. Numbers filled it. Folders opened. A story told itself in signatures and shipments and low-res security stills of crates moving in the night. We redacted the names of people who were stupid but salvageable. We left visible the names of men who had turned stupidity into commerce. When we played the segment of a recorded call where Charles bragged about “owning more than paper,” the room made a sound I’d been waiting to hear: disbelief dropping its mask and revealing anger.

The agents exchanged looks that meant “go.” I could feel it—a building’s temperature changing when justice puts on its coat.

And then the floor shuddered.

You don’t misinterpret an explosion if you’ve ever heard one up close. It has a grammar. This one spoke in concussive clause and hot punctuation. Smoke swung like a door. A camera toppled. The crowd bent as if praying, then began the human math of exits.

“Service corridor,” Ji shouted into her mic. “North wing—fire door overridden.”

Monroe didn’t explode with fear. He exploded with purpose. “Seal the main hall!” he barked, voice like a siren. Agents moved without theatrics. People followed orders not because they were frightened, but because they trusted the man giving them.

Through the smoke, the past walked toward me.

Charles—limping, bleeding at the sleeve, eyes bright with that manic confidence bullies wear when they believe the room will always bend—came into focus, gun in hand. A guard lay behind him, too still. The image stung worse than the scar.

“You really thought you could outsmart me, Maya?” he called, voice cutting through alarms.

“I didn’t,” I said, surprised by how calm I sounded. “I just let you underestimate me.”

He raised the gun.

I raised mine first.

Training is a prayer you say with your whole body. I sighted left of center to spare a heart I didn’t want, squeezed, and watched his shoulder snap back. The pistol hit tile like a confession. He stared at me as if I’d broken a law he wrote. “You wouldn’t,” he gasped. “You don’t have it in you.”

“I have more than you taught me,” I said.

Agents folded around him like a net that finally remembered it was stronger than the fish. He raved, he cursed, he threatened the kind of darkness his money once rented by the hour. It didn’t matter. His words fell into a space that no longer echoed back.

Monroe moved to the fallen guard. He pressed two fingers to the carotid, waited, pressed again, shook his head once, as if refusing a world that kept making this mistake. Then he stood and looked at me—not with fury at me, but fury beside me—the kind of anger that turns toward the right enemy.

“We’re done here,” he said.

We weren’t. Not yet. But the part where he dictated the script was over.

Part IV — A Sentence Long Enough for Peace

The trial took months because truth wears boots and paperwork wears cement. Assistant U.S. Attorney Tran treated my evidence like a fragile relic and a hammer. She built her case one unromantic line at a time, stacked enough counts that even Charles’s smug grin began to crack. When the verdict came—guilty on attempted murder, guilty on conspiracy, guilty on trafficking counts whose specifics make decent people close their eyes, guilty like a full stop—it didn’t feel like triumph. It felt like air after drowning.

The judge looked at him and said the words that should be printed on the front door of every courtroom: “Your money did not purchase permission.” Life without parole. He tried to speak. The gavel didn’t listen.

His empire, such as it was, fell like a building gutted for cameras. Partners flipped. A defense contractor resigned in disgrace and underlined it with an indictment. A lobbyist discovered ethics just in time to trade it for a lighter sentence. The shipping magnate tried to convince the world he’d only trafficked in citrus. We found the names of the girls hidden in crates and replaced his lawyers’ nouns with theirs.

As for the guard—Officer Ramon Tisdale—he was twenty-six, had a sister who worked nights, a little dog named Penny, and a stubborn belief in double-knotting his laces. We set up a fund for his family. I spoke at the quiet memorial in my dress blues and didn’t say hero or sacrifice the way brochures do. I told them what he did: he went to work because he believed in doors that stay locked for dangerous men and opened for everyone else.

My recovery became something else—less about muscle and more about meaning. Marisol signed off the day I left my cane leaning in a corner and forgot it there. The scar stopped predicting rain and started telling time in gratitude.

I took the podium again months later for a different ceremony—my reinstatement to full duty. Monroe stood beside me as always, a mountain that never claimed to be a god. He handed me back the medal that had been interrupted by blood and whispered, “You fought a war no soldier should ever have to fight. And you won.”

I looked out at the faces—men and women who knew the sound of rotors and the taste of grit—and said the truest summary I could add to a life like mine: “Pain taught me how to survive. Revenge taught me how to rise. Forgiveness taught me how to live.”

Forgiveness didn’t mean forgetting. It meant setting down a weight that wasn’t my job to carry. I didn’t write to Charles. I didn’t visit. I let the system hold him because I didn’t need to anymore.

Instead, I wrote to someone else. I found an address through a mutual friend and sent a letter to the woman I used to be—the seventeen-year-old who ran with bruises under a hoodie and a mind built on someone else’s lies. I wrote it like a field guide:

You are not broken, I told her. You are wounded. Wounds heal.

You are not his story.

You are yours.

I tucked a copy by my mother’s photograph, next to my medal. “We’re free now, Mom,” I whispered. “Finally free.” The frame caught afternoon light and made the ribbon glow like sunrise caught its breath in silk.

Life kept doing what life does—offering mornings tired and beautiful, missions that mathed themselves into logistics instead of glory, people who needed food more than speeches. I asked for the kind of assignments that get shoes muddy and hands useful. In Puerto Rico after a storm, an old woman pressed my knuckles to her forehead and called me mija. In a floodplain two states away, we built a bridge out of trucks and stubbornness and watched school buses cross like victory parades.

Sometimes reporters asked for the story again. I told it, but I told it smaller, so the fire wouldn’t eat the whole house. Young soldiers wrote me emails. I wrote back. A clinic opened on base funded by the reception I’d hijacked. It had three counselors, two rooms that felt like living rooms instead of interrogations, and a sign on the wall that read, “You are believed.” I kept my first session. I learned how to say hard sentences aloud and not feel treason to the warrior I’d been.

Monroe retired the year after. He didn’t leave. Men like that never really leave. He sent me a postcard from a cabin where the pines had a say and signed it with a joke: “Four stars exchanged for four walls and a porch. Good trade.” I wrote back that leadership doesn’t require rank; it requires showing up with your whole self and a spare hand.

The last time I saw Charles was in a clipped line in a paper—a prison transfer after a fight he started and lost. I didn’t clip it out. The only place his name still lived in my house was on an old envelope I’d never mailed, the one I kept to remember that I chose not to let him define my endings.

On the anniversary of the first ceremony, I stood alone in that hall. The staff let me in after hours. The chandeliers hummed. The stage remembered. I walked to the spot where my knees had hit, knelt on purpose, pressed my palm to the wood, and stood easily. I could almost hear the echo of Monroe’s fury turned into protection, feel the gravity of the room choosing a side.

They say revenge burns everything it touches. Sometimes it does. Sometimes, used carefully, it burns only the rope that’s been around your throat. Justice is the water you drink after. Peace is learning how to breathe the ordinary air again.

I wear the scar like a map, not a monument. It points home. It points forward.

When cadets ask what I learned, I don’t tell them about pistols and podiums first. I tell them about the quiet between two waves when you decide who you are. I tell them there is a difference between winning and becoming, and if you have to pick, choose becoming. The rest follows.

And when I walk past my mother’s photo at night, I touch the corner of the frame, a habit that feels like prayer, and say the sentence she gave me permission to keep: softness saves. I didn’t understand then. I do now. It wasn’t weakness that kept me standing while blood soaked my uniform. It was the stubborn gentleness to refuse becoming what hurt me.

The general beside me exploded in fury. I exploded in purpose. The room broke. Then it learned. And so did I.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I Was Mistaken for a Civilian — Until the Colonel Said, ‘Ma’am… the Black Widow of SEAL?’

At the airport, she was just another woman in jeans—until one quiet word froze the entire lounge. No medals. No…

CH2. I Thought It Was Just a Family Party, Until My SEAL Said, “This Isn’t a Birthday… It’s a Setup.”

It was supposed to be just a family party — laughter, candles, and a few harmless speeches. But halfway through…

CH2. I Thought My Father Died in 1991 — Until I Saw His Signature in the Navy Record…

They told me my father died in 1991 — a Navy officer lost in a mission no one would talk…

CH2. At the Hearing, He Said I Didn’t Belong — Then the Judge Read: “Admiral Morgan.”

He called me a disgrace — right there in front of the judge. My father tore the envelope open, ready…

CH2. My Father, An Admiral, Secretly Gave My Promotion To His New Wife’s Daughter — BUT HONOR NEVER LIES

He took my promotion and handed it to his new wife’s daughter — the one who’d never worn mud, sweat,…

CH2. My Father Mocked Me in Front of 500 Guests — Until the Bride Said: “Admiral… Is That You?”

At my brother’s lavish wedding, my father raised his glass and humiliated me in front of 500 guests, calling me…

End of content

No more pages to load