At Christmas Dinner, My Mom Said “You’re Not on the Will Anymore” — So I Gave Her a Present That Turned Everything Upside Down

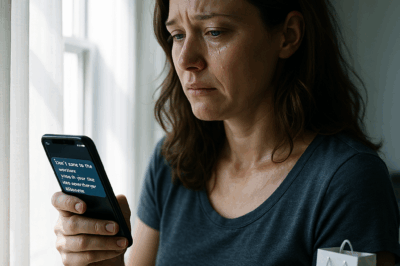

Part I — The Sentence That Cut the Room in Half

Christmas makes everything look softer than it is. Ribbon hides sharp corners. Frost turns dead grass into chandeliers. Even people who hate each other sit shoulder-to-shoulder and pass the potatoes because a song on the radio says they should.

We were halfway through the roast when my mother lifted her wine glass and cleared her throat like she was announcing a winner at a gala.

“Before dessert,” she said, “I have an update that concerns the family.” Her eyes skimmed over my father, who studied his plate as if reading braille, then over my younger brother, Michael, who was already smirking, then rested on me.

“You’re not on the will anymore, Rebecca. I’m sorry, but… certain choices have consequences.”

The words landed with the same effect as a fork dropped on tile—small sound, big room, loud anyway.

I didn’t blink. I watched the candle tip quiver in the draft and thought, calmly, about the box underneath the tree with her name on it. The one tied in navy satin and tucked behind the poinsettia like a secret.

David’s knee brushed mine under the table—one quiet question. I slipped my hand into his and squeezed back: I’ve got it.

Michael leaned back in his chair, stretching like a cat who has clawed something expensive. “Tough break, Bec,” he said, sweet as sour milk. “You don’t marry a trust fund and then expect to be treated like you did.”

Across the table, my mother—Patricia Thompson, president of the Women’s Auxiliary, benefactress of half the charities in Portland that photograph donors in pearls—turned the diamond on her finger. “You’ve made your path,” she said, “and I hope it brings you joy. But I won’t reward… recklessness.”

Recklessness. As in: marrying a tattoo artist who reads Neruda, sends his mother a check on the first of every month, and keeps spare blankets in his trunk for houseless clients who come in for cover-up work. Recklessness, in my mother’s dictionary, translates to outside my club’s address book.

I swallowed, once. The room had that hushed winter sound that happens just before a storm—the one you can feel in your teeth.

“Thank you for the update,” I said, smiling in a way I’d practiced in the mirror of St. Mary’s night shift bathrooms. “And I have something for you too, Mom. Can we do gifts before dessert? I think you’ll like mine.”

Her eyes brightened. Applause for the lady who never loses the room. “Of course, darling,” she said, and dabbed at the corner of her mouth though nothing had spilled.

We moved to the living room—fireplace on, Bing Crosby competing with the hum of the espresso machine, family photos curated into a museum of selective memory. I handed my mother her present.

“Oh, Rebecca,” she trilled, already performing gratitude for an audience. She untied the satin ribbon, lifted the lid, and frowned. Tissue paper. A walnut music box. A silver key.

“What is this?” she asked, laugh-light.

“A family song,” I said.

She twisted the key. The first notes of “The Holly and the Ivy” tinkled through the room. The melody swelled—bright, almost cheerful—and then, unmistakably, the song broke. The mechanism clicked. The false bottom lifted.

Below, wrapped in archival sleeves, lay paper. Not scented stationery. Not handwritten apologies. Documents. A notarized letter. A USB flash drive labeled in my grandfather’s precise block print: For Patricia, if you forget. For Rebecca, when she needs it.

She stared. The room didn’t breathe.

“What is this?” she asked again. Quieter, this time.

“Your Christmas present,” I said, as calmly as if I were naming herbs. “Granddad’s real will. The one he signed six months before he died. And a few things you’ve been telling yourself would never come to light.”

Her throat moved. My father set down his coffee so gently the cup didn’t even clink. Michael laughed—one sharp, ugly burst that sounded like metal—a reflex more than a joke.

“Rebecca,” my mother said. “Don’t be theatrical.”

“I’m very tired, Mom,” I said. “I don’t have the energy for theater.”

I turned to David. “Would you help me with the laptop?”

He nodded, set it on the coffee table, and connected the USB drive. The TV screen over the mantel—usually a parade of curated family slideshows—glowed awake with a desktop. A folder opened.

1. Executed Will (Rev. 6) — J. W. Thompson

2. Trust Schedule B: Separate Personal Assets

3. Correspondence (Harrison & May, LLP)

4. Financial Records: Transfers & Charitable Disbursements

5. Medical Records — R. Thompson (stress-related) [consent attached]

6. Letter to Patricia

7. Letter to Rebecca

“Stop this,” my mother whispered, but it sounded like a suggestion, not a command.

I clicked the first file. The firm’s letterhead sprang to life. Last Will and Testament of Jeremiah Walter Thompson. Rev. 6. Executed: June 12. There were the signatures. There were the witness initials. There was the clause:

In recognition of the undue influence and moral coercion exerted by my daughter Patricia Thompson over my granddaughter Rebecca Thompson, and in gratitude for Rebecca’s integrity and service to others, I bequeath the entirety of my separate personal estate—held outside corporate assets—to Rebecca outright, free of trust.

Beneath that, a list: the lake cabin he’d loved more than the club; the war bonds he kept in a box labeled Fishing Lures; the vintage Steinway that my mother had always assumed would live in her sunroom; the Norman Rockwell sketch; the Telemachus Portfolio, his private investments. A figure at the bottom that made Michael suddenly forget how to blink.

“You forged something,” he said, voice cracking like ice in water.

“It’s notarized,” I said. “By Harrison & May, the firm you’ve been e-mailing from my mother’s account for two years, asking them to ‘clarify’ clauses to your advantage.”

I clicked another folder. E-mails slid onto the television—a polite exchange between my mother and the estate attorney, couched in soft words like concern and interpretation alongside hard-angled phrases like re-characterize in trust and advance to Michael discreetly. A trail of withdrawals from Family Charitable Fund to an account Michael used to pay his rent, his car, his pinball addiction dressed as consulting.

The room began to tilt. Somewhere, the music box continued to play a broken hymn.

“Enough,” my father said hoarsely. “Turn it off.”

“It’s on a loop,” I said, and clicked 6. Letter to Patricia.

My grandfather’s handwriting filled the screen:

Patty,

*I love you. I always will. But you are not a queen and this family is not a court. You have confused names on a board with the weight of a life.I will not reward cruelty disguised as standards—nor a long habit of telling yourself that the people you control deserve it. If you disinherit Rebecca for refusing to be controlled, you will have disinherited me, too.

If you have opened this, it means you made the choice I begged you not to. So be it. Then Rebecca needs this more than you do.*

—Dad

My mother’s hand—always so steady with a martini—trembled. “That old man,” she said, voice thin as glass. “He never understood what it takes to keep a family—”

“To keep an image,” I said.

David’s hand was warm around mine.

Michael stood so abruptly his chair scraped the floor. “This is garbage,” he said, and pointed at the flat screen as if it were a person. “You hacked something. You… you’re with him now,” he flicked his chin at David, “and you think you get to shame us?”

“What you do in the dark is always insulted by light,” David said quietly. “It’s not about me.”

I clicked 7. Letter to Rebecca. The handwriting softened:

Becca,

*If you are reading this, you have done the bravest and most ordinary thing—chosen yourself when the people who should love you refused to.The trust schedule is yours. Use it for a life, not a performance. Buy the small ugly house you love. Give what you want to who you want. Play the piano in the afternoons with the windows open.

And when you hold your baby, hold him in a world you built—not one set for you.*

*I am proud of the nurse you became, proud of the granddaughter who brings real casseroles and not just flowers to funerals.Don’t let anyone tell you love is earned by obedience. Love does not need an audience.*

—Granddad

My throat closed. I felt our daughter tumble in my belly—one heartbeat answering another.

Mom stared at the screen, then at me. For the first time in thirty years, I saw that she was not bulletproof. People who build a fortress out of opinion always assume the drawbridge will hold.

“You planned this,” she whispered, equal parts awe and hatred.

“I prepared,” I said. “Because every time I told you who I was, you edited it until it looked like you.”

She opened her mouth, closed it, then did something I didn’t think she remembered how to do. She looked at my belly instead of my face. Not at the dress, not at the choice of husband, but at the outline of a life that had nothing to do with her optics.

She looked away.

I closed the laptop. The fire popped like punctuation. “David and I are leaving,” I said, gently. “We have a son to get home to.” The first truth I’d allowed myself to say aloud that was still a secret in this room.

“You’re… pregnant,” my father said, as if the word were a code he’d misremembered. He stood—slowly, like a man who had put down something heavy on the wrong shelf and was embarrassed to ask for help lifting it back.

I stood, too. “I was going to tell you today,” I said. “And then you told me I was dead.”

We left our mugs half full. We left the music box playing its broken carol. We left the gift wrap on the rug like confetti after a parade that wasn’t for us.

We walked out of my mother’s house into clean cold afternoon air. It tasted like a beginning.

Part II — The Will That Was a Map

Three days later, my mother’s lawyer called. His voice was neutral in the way bridges try to be neutral between two angry rivers. “Ms. Thompson,” he said, “your mother would like to contest certain elements…”

“She can contest gravity,” I said. “It will keep working.”

He coughed—half-laugh, half-caution. “Your grandfather’s documents are airtight. He was careful. There is also…” He paused, choosing words the way men in suits choose tie widths.

“What,” I pressed.

“There is a conditional letter he left for me, to be delivered at my discretion if I felt that your interest would be harmed by any delay. He anticipated… a struggle.”

“Of course he did,” I said. “He raised her.”

A week later, in a conference room that smelled like copy paper and men who prefer mahogany, I signed a stack of documents that transferred the lake cabin (blue, peeling, perfect) and a portfolio I couldn’t pronounce into my name—outright. I left with a folder, a key, and a feeling like I had stepped into a pair of shoes that had been bought for me long before my feet knew which way to point.

David drove us to the cabin that weekend. The cold was friendly there. The dock was a skeleton in the fog. I put my hand on the piano bench and felt a pulse through the wood—memory, maybe, or just the old house settling around a new truth.

Back in town, things rearranged themselves with a violence that looked from the outside like grace. Invitations dried up for my mother the way ponds evaporate in August. The club, which pays tithes to optics, placed her on committees that meet in rooms without windows. Her friends—who drank her gin and complimented her hydrangeas—rehearsed sympathy while sucking lemon seeds from their teeth.

My father, who has always made his money sound like a virtue and his silence sound like survival, asked to meet me for coffee. He sat down in a booth and looked older than the portrait over the mantel in the dining room he cannot enter without whistling.

“I read Jeremiah’s letter,” he said. “He called you by your name, not by your place. I’ve failed you at that.”

I didn’t smile. I took a sip of a drink my OB/GYN would approve and said, “How are you?”

He stared into his cup. “Embarrassed,” he said slowly. “Which is at least honest. I should have asked you about him. I should have asked you why. Instead I asked you to wait until your mother could bear the thought of a son-in-law who doesn’t own a blazer.”

“David has a blazer,” I said. “He only wears it to funerals. Maybe weddings.”

“Bring him,” my father said, trying a smile. “To dinner. Without your mother. Let me… let me try again. With him. With you.”

We did. He set two extra plates. He tried not to ask questions the way my mother asks questions—as traps. He laughed at David’s story about the man who requested a tattoo of his ex-wife’s name on a goldfish (“So if I feed it, she grows,” the client had said, which is both poetry and a cry for help). It wasn’t perfect. He called the shop “your little place” once and corrected himself, cheeks coloring to match the marinara. But we left with leftovers and an invitation to look at baby photos of me in a onesie that insisted I was Daddy’s Girl. I drove home thinking maybe my father had decided to be a human instead of a suit with a heartbeat.

Michael didn’t call. He posted. “Families are complicated,” he wrote on an Instagram caption beneath a selfie taken in a bathroom with three different colognes visible. “You do what you can.”

What he could do, evidently, was continue to be kept.

Until he couldn’t. Divorce filings, like incoming weather, change the barometric pressure inside houses. I know this because overnight my mother started attending church again and my father started attending the gym again and Michael asked me—me—for help finding a job at the hospital.

“You know… filing,” he said, like the universe wouldn’t appreciate the symmetry.

The irony didn’t amuse me. I sent his resume to the HR inbox the way you throw a bottle into a lake—on principle, not expectation. When he got an interview, I texted him the time and place and said, “Do not be late. Do not be high on vape. Do not call the women ‘hun.’”

He was late. He was sober, I think. He called the hiring manager ma’am and she did not set him on fire. He didn’t get the job, but he got a different one, at a shipping center, and showed up for six consecutive days, and then twelve. Progress is a coffee stain you pretend not to notice until you realize you’ve washed the mug and the ring is gone.

I did not invite my mother to my twenty-week ultrasound. I invited David and his mother, Ana, who cried when the tech typed HELLO WORLD next to the pixelated face of our daughter (because of course she turned out to be a daughter; poetic symmetry is not only for novels). Afterward we ate tacos from a truck in the hospital parking lot because celebration does not have to be served on china to be holy.

I did not change my phone number when my mother started mailing cards. For the little one, they said, with checks made out to baby. I returned them unopened, with a note in my own tight, nurse-practitioner script: When she is a person and not a bargaining chip, we’ll reconsider.

I did not go to the country club luncheon where someone toasted women who know their place and three wives pretended they’d never seen me pass through the lobby in scrubs at 2 a.m. I did go to a baby shower thrown by David’s family where his aunt Ester brought a diaper cake the size of a small planet and two cousins argued lovingly about whether the baby should learn Spanish first or just equally with English and then decided to handle it with dueling cumbias in the living room.

A week before my due date, my grandfather’s lawyer called again. “Mr. Thompson referenced a safety deposit box related to the cabin,” he said. “He left instructions for you to open it ‘on a day she thinks she’s won.’”

“I’m too tired to win or lose,” I told him. “I’m growing a person.”

“Then open it after she says something terrible,” he said.

“Sir,” I said, “we could be here until retirement.”

I waited until something terrible arrived anyway—my mother left a voicemail saying she had “registered” the baby’s name with her bridge club’s new-baby list as Elizabeth Anne. “Because we need to reclaim the family line,” she said.

Our daughter’s name is Lily. It always had been.

I drove to the bank with ankles like bread loaves and opened the box. Inside: the deed to the small adjoining lot my mother had tried to sell as “excess land” to a developer who wanted to put up short-term rentals on the lake. A letter in a metal frame addressed to my daughter: For the small girl who will raise rabbits by this pond. Plant blueberries where the soil is stubborn. Do not sell this for a kitchen renovation.

I laughed until I cried and then laughed again because my laugh has always sounded like a sob blurred at the edges.

Two days later, I gave birth to Lily on a Tuesday morning at 10:13 a.m. She arrived furious, beautiful, with all the hair in the world and lungs that announced themselves to the neighboring county. David sobbed. I cursed like my grandmother knitting in church. Ana held my foot and yelled in English and Spanish and at one point in something that might have been prayer.

We took our baby home to a small rental with peeling paint and a cast-iron pan we were not supposed to put in the dishwasher and it felt, unequivocally, like a palace.

Part III — The Knock That Changed Direction

Boundaries are easier to hold with a baby on your chest. It’s physics. It’s chemical. It’s love with fingernails. I didn’t answer my mother’s first three attempts at “Can we meet her?” I didn’t answer the fourth. On the fifth, I texted: Not yet. On the sixth, I added: And you do not get to name someone you haven’t met.

She sent a Christmas card. The front said Peace. Inside, she wrote, I don’t know how to do this. But I think I want to try. I put it on the mantel because I felt petty and then felt childish and then left it there because it turns out I can be both and still be right.

When Lily was two months old, my mother showed up at our apartment with something ridiculous and perfectly her—a silver rattle in a velvet box—and something unexpected and perfectly human—a jar of chicken soup she had actually made. Then she did something I would bring up at least three times a year for the rest of our lives. She said, “I’m sorry.”

She said it like a person in a foreign country ordering food in a new language—careful, slow, afraid of the wrong accent but finally just leaping.

“Not for the will,” she clarified. “For making love into a ladder. For thinking prestige could fill a house better than people. For forgetting your grandfather taught me better and I chose worse. For not seeing him in you.”

I cried. Not because I forgive quickly but because relief is an animal. It has weight. It settles in your arms and purrs and you realize you haven’t been sleeping because you’ve been holding breath like a shield.

We set a rule. She could see Lily if she left her judgments at the door with her shoes and never—never—told my daughter who she was allowed to be. If she crossed that line, the line would become a wall. She nodded. When she crossed it two months later in the grocery store by telling a stranger who complimented my baby’s chuubby cheeks that “we will be watching her weight,” I walked out and didn’t answer her for three weeks. The boundary held. She learned.

My father learned to send texts without punctuation that somehow felt like love: stood up to the board today proud of you proud of me.

Michael learned to stop saying “when Mom helps with rent” in front of his new boss. He learned to make grilled cheese without setting off the smoke alarm. He learned that the kid stocking shelves next to him had two jobs and two classes and still smiled at customers even when they were cruel, and that humility in the wild looks like that.

David learned how to swaddle in under forty-five seconds. He learned the lullaby Ana sings has magic in it, because everything she touches does. He learned to let me sleep longer than he could and that this wasn’t a competition; it was a relay.

I learned the piano at the cabin is a better therapist than most insurance will cover. I learned I can play scales with Lily on my lap if I use only my left hand. I learned blueberries grow better if you talk to them like people.

And my mother learned something my grandfather had tried to teach her: money looks smaller from the other side of the lake.

Part IV — The Second Christmas

A year to the day after Patricia Thompson announced I was dead to her, I set a gift on her coffee table and told her to open it. She flinched like a person who has been handed a memory they are not ready to hold.

The room was the same, mostly—fire lit, Bing still believing in miracles—but the air was different. My father stood next to my mother in the way he hadn’t in decades. Michael arrived with store-bought cookies he didn’t try to pass off as his own. David bounced Lily on his hip like a Kermit-carrier.

My mother removed the ribbon with both hands, not because it was fancy, but because some things should be done without haste. Inside: a framed photo of my grandfather holding me when I was tiny and furious and wearing a bonnet I would later burn; a Polaroid of David holding Lily the hour she was born; a letter in my own tight print:

Dear Mom,

*Last year you gave me your inheritance definition. I gave you a mirror. We both learned, maybe, that love and money don’t share a checking account.This year, I’m giving you membership in a family where no one has to audition. The fee is relentless honesty and the perk is unconditional presence. Don’t squander it. We won’t either.*

—R.

She put the frame in her lap and covered her face with both hands. When she dropped them, her mascara had done its worst and she did not care.

“I don’t deserve a second chance,” she said.

“Correct,” I said. “But Lily deserves grandparents who learned something.”

She laughed through the mess—an ugly laugh, a human laugh—and reached for her granddaughter, who reached back, because babies are better than theology.

After dinner—where we ate food I grew up with and food my husband grew up with and no one declared either superior—we took our plates to the sink. My mother reached for mine and I let her take it. Small grace, small penance.

I stood at the window and watched snow begin—flakes so fat they looked like napkins. David slid an arm around my waist and murmured, “Your grandfather would be unbearable with joy.”

“I know,” I said. “He would be insufferable about the piano.”

We drove home late, Lily asleep in the car seat, the lake road dark and familiar. The cabin porch light, which had not belonged to me for thirty years and had now belonged to me for one, glowed like a heartbeat.

Inside, we put the baby in her crib. I sat at the piano and laid my hands on the keys. I did not play a carol. I played a chord that sounded like a door opening.

My phone buzzed. A message from my grandfather’s old lawyer. I frowned, opened it. Found one last envelope in the vault. Jeremiah labeled it “for when she forgives herself.” Do you want me to shred or send?

I stared at those words (for when she forgives herself) and realized my mother had work to do that had nothing to do with me. I typed send it to her and hit send.

The fire hissed, a log falling into a new shape. David sat beside me and leaned his shoulder into mine.

“Big day,” he said.

“Big year,” I corrected.

He kissed my temple. “Big life,” he said.

The snow fell harder, practical magic. I let my fingers find the broken notes of “The Holly and the Ivy,” and somewhere halfway through, the melody mended itself on its own.

I don’t know if that’s what forgiveness is. I don’t think it’s supposed to be tidy. I think it’s a song you keep playing until the mechanism remembers how to stay in time.

So here is the ending you asked for, complete and clear: My mother lost her fiction and found her daughter. My father traded silence for spine. My brother learned to stand without a subsidy. My grandfather’s last will did not simply move money; it moved a woman’s life. And mine moved with it—out of an inheritance that required obedience and into a legacy that requires courage.

This Christmas I did not get disinherited. I got something better: a family I chose and a future I can explain to my daughter without lying.

And that’s the kind of will I want my name on.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. “Don’t Come To The Wedding,” My Mom Texted. “You And Your Kids Just Make Things Awkward”. What happens next turns their picture-perfect family into complete chaos.

“Don’t Come To The Wedding,” My Mom Texted. “You And Your Kids Just Make Things Awkward.” What happened next turned…

CH2. I went to my mountain lodge to refresh, and found my sister, her hubby, and his family living there.

My Mountain Lodge Was Supposed to Be Quiet. Instead, I Found My Sister’s Christmas Party—In My House. Part I —…

CH2. I Rushed Home From Vacation For My “Dying” Mom… But Found 3 Abandoned Kids Instead.

I Rushed Home From Vacation For My “Dying” Mom… But Found 3 Abandoned Kids Instead Part I — The…

CH2. My Parents Told Me to Sleep in the Garage, But Froze When the Black SUV Stopped at Our Door.

My Parents Told Me to Sleep in the Garage, But Froze When the Black SUV Stopped at Our Door Part…

CH2. Break Down The Door, This Is Our Son’s Apartment — My Mother Came With Dad And Brother To Break Into..

Break Down The Door, This Is Our Son’s Apartment — My Mother Came With Dad And Brother To Break Into……

CH2. During Family Dinner, Dad Said ‘You’re No Lawyer’—Then His Case Landed On My Desk

During Family Dinner, Dad Said “You’re No Lawyer”—Then His Case Landed on My Desk Part I — The Last Supper…

End of content

No more pages to load