At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake

Part I — The Invitation With a Knife Inside

The envelope was thick, the kind that says someone still believes cardstock is currency. Cream with a raised crest, my cousin’s name gilded like a promise I wasn’t sure I wanted.

I almost fed it to the shredder. Eleven years of “we miss you,” followed by eleven years of “also, we told Aunt Ruth you’re unstable,” will train a hand to protect itself. But I’d been running a long time. And curiosity, that soft animal, tilted its head.

The ballroom shone like prayer under chandeliers that had never known dust. Gold, glass, fabric that whispered money whenever someone moved. I told Michael I didn’t have to go. He told me we weren’t hiding anymore. He smoothed a palm down my spine. “You don’t owe them a performance,” he said. “Just your presence.”

For the first time, I didn’t feel like armor was required. I wore a simple slate dress that moved when I did. I wore my own name, the one I had soldered together from years of humiliation and work. I wore the certainty that if trouble arrived in a suit and pearls, I could still breathe.

My mother spotted me first. Surprise lit her face, then turned into the old steel— that quick tightening around the mouth, the look that had policed every hemline I’d ever loved. She leaned toward my father. He nodded like a man authorizing a storm. Within seconds, his hand was around my elbow, firm as a courtroom order.

“What are you doing here?” he asked, voice soft enough to be heard only by the people he hoped would watch me bow.

“I was invited,” I said, and turned my palm so his grip met nothing but air. “It’s family, isn’t it?”

“You’re not welcome.”

He stepped in front of me. Conversations stuttered. Head after head turned like a field of wheat in a sudden wind. The old heat crept up my neck, the one I knew from the night they locked me out with one suitcase and the sentence, Don’t come back.

Michael’s hand found the small of my back. He didn’t shove. He didn’t posture. He didn’t meet my father man-to-man. He said, pleasantly, “We RSVP’d. We’re here to congratulate the couple. If that’s a problem, we can certainly discuss it with the planners.”

The name Dr. Michael Hale moved through the room like electricity. Harvard cardiac surgeon. The man who’d threaded new life into people who had run out of options. He didn’t drop it like a title; it fell from other lips in a murmur that loosened my father’s jaw.

My heels clicked against marble as I walked past. Each sound felt like a door closing that I had once begged to open.

Across the room, my sister turned, smile staged for the perfect candid. Grace. Twenty-five now, poured into silk the color of moonlight, pearls winking at her throat like a secret’s punctuation. She had been raised to be the painting on the wall and the wall itself. The favored daughter is a role you play until it grows around you like bark.

When she saw me, the smile faltered, as if her reflection had moved without her.

Once, we had shared a room. Once, she had told me secrets under blankets scented with lavender linen spray. Once, she had climbed through windows with me when our house turned from home to correctional facility. Then our parents looked at us and saw an aristocrat in training and a problem to be solved. They picked a student to sponsor and a story to tell at parties. Their choice became Grace’s wealth and my exile.

I didn’t mourn the past as I crossed to the couple. I congratulated them. I shook hands. My cousin’s fiancé, Daniel, had a handshake like someone who had never needed to prove anything. “Amber Collins,” he said (I use my middle name professionally; it keeps my inbox tidy). “The Mova CEO. Your postoperative monitoring work is staggering. We’ve been following the readmission data. I’d be honored to hear more.”

There it was—the shift. Not the old whisper, isn’t that the difficult daughter? but a new murmur: she built something.

From the edge of the crowd, Grace watched, flute of champagne trembling at the lip. Behind her, my mother counted—guests, optics, risks. My father stood with that shrinking posture men get when their script is no longer the one onstage.

We lasted until dessert before something snapped under the weight of years.

My mother approached, smile lacquered on, eyes flat as coins. “You’ve made your point,” she murmured. “Now leave before you ruin the evening.”

“Ruin it,” I said lightly. “Or expose it?”

“You’ve always been jealous,” she answered, the words as tired as the dress she wore two Christmases ago. “Always trying to steal Grace’s spotlight.”

I laughed, not kindly. “You stole my tuition to send her to conservatories while you told people I dropped out. You stole my future and called it investment. The only spotlight I want is the kind my engineers use to sterilize clean rooms.”

Michael’s shadow fell beside mine. “We’re here to celebrate the couple,” he said to my mother. “If you can’t manage civility, perhaps dessert is best had elsewhere.”

Her lips pressed thin. Control slipped, that old drug.

On the balcony, the night air felt like water after running too long in a room with no windows. Grace found me there. She stood at the rail, perfume sweet and familiar enough to make me want to kneel and tie her shoe like I had when we were eight.

“Why did you come back?” she asked. The words wobbled. “You were supposed to stay gone.”

“I came back because I stopped being afraid of you,” I said. Then, because sometimes mercy is the only weapon that doesn’t ruin the hand that holds it: “And because I wanted to see you as a person again.”

Her throat moved. Tears rose to a line she had been trained to swallow. “Without them,” she whispered, “I’m nothing.”

“That’s the lie they sold you,” I said, looking at the city, not at her. “Not the truth I bought for myself.”

We might have braved it there. Found a bridge, or at least a plank. Fate, however, prefers theater.

Daniel’s voice rose from the ballroom behind us. “Amber,” he called, warm but edged, “may I ask you something?”

A hundred heads turned, hungry for sport. I went back inside like a woman who knows her footing on polished floors. “Yes?”

“You graduated…” He glanced at Grace, then at me. “From Stanford?”

“No,” I said. “Community college. Then State. Nights. Three jobs. No family money. Only stubbornness.”

Not a brag. A bone.

He blinked. “It’s strange. I was… told otherwise.”

My father moved toward him, hands slicing the air. “We don’t need to—”

“I’m not asking you,” Daniel said, softly. “I’m asking her.”

The room inhaled. My mother’s smile cracked. Grace’s glass shook until a drop of champagne spilled onto her palm and made a small comet toward the marble.

I didn’t tell the whole story there. A ballroom is a poor confessional. But the geometry of power rearranged itself in front of people who had believed my parents’ brochure for a decade. You can’t control a narrative once the cast starts improvising.

By the time we left, holding two slices of cake wrapped in napkins for our son Leo (who photobombed half the evening like destiny in sneakers), the whispers had changed. They were saying words like resilience instead of rebellion.

In the car, Michael squeezed my hand. “You did it,” he said.

“Did what?”

“Stood where they wanted you to kneel and didn’t ask for permission.”

I looked out at the city, all those windows with people inside them thinking their families were the center of the world. “Control only works if you sign the consent form,” I said. “I didn’t.”

Part II — The Revising of History

The fallout arrived in texts from cousins and emails from people who had always CC’d me on apologies they never sent. Daniel, it turned out, had the same allergy to being lied to that saved me in my twenties. He asked questions. Grace gave answers that gave birth to more questions. The story frayed. My parents flexed old muscles—discrediting, distracting, insisting—but their grips didn’t hold.

I did nothing. The absence of my panic was a new country I wanted to learn to live in.

Then came the call from the aunt who had stayed friendly in that careful family way—liking photos but never liking them too enthusiastically. “Your father wants to meet with Michael,” she said. “Alone.”

Michael went. He ordered coffee. He listened. He came home with a face I had only seen after a fourteen-hour surgery—a face that has watched someone else decide whether to live.

“He apologized,” he said.

“For what?”

“For stealing. For lying. For making it impossible to love him without hating yourself a little.”

“Did you believe him?”

“I believed that he finally saw the bottom and wanted to stop falling.”

A week later, my father and I sat across from each other at a diner where you could still get eggs for under five dollars if you knew how to look at the menu. He aged a decade under the fluorescent lights. The first thing he said was my name like it was a word he didn’t want to mispronounce.

“I told myself I was protecting the family,” he said, staring at a napkin he kept folding and unfolding. “I was protecting my reputation from my fear. I’m sorry.”

If this were fiction, I would tell you that I forgave him there. That we embraced next to the pie case and years dissolved. Real life is slower. Trauma has the half-life of uranium. I said, “Thank you.” I said, “That mattered.” I did not say, “You’re back.” People are not baseballs you throw to yourself in the yard until your hand stops hurting.

We made rules. They broke them once. I adjusted them. We built a fence, and then we ate sandwiches on opposite sides of it until we could trust the gate.

My mother was a longer battle. Control is a religion in some women, and she had been a priest since 1986. She apologized with a performance quality that could have sold out off-Broadway. I told her to say it again without the tears. She did. She cried anyway, not in control this time. We agreed on supervised visits—with my boundaries, not hers. When she snapped once at Leo for forgetting his fork, I handed her her coat and said we were done for the day. She cursed me with the fluency of a woman who had lost her grip on all her dictionaries. The next time she visited, she brought plastic forks and an apology for Leo.

“Everyone pays for access now,” I told Michael that night. “Even the originals.”

Part III — The Audit

Control runs on language. So does money. I hired Janet to audit the years my parents took from me and renamed them “gifts.” I sat with her while she created categories from my life: Loans We Pretended Were Not Loans, Emergencies That Lasted All Summer, Birthdays That Were Really Utility Bills.

$127,000 stared back at me.

“Do I sue?” I asked the lawyer on my lunch break, leaning against a brick wall behind my office where the delivery guys take smoke breaks and wisdom.

“You can,” he said. “You would win money and lose your peace. Ask yourself whether being right is worth being haunted.”

I took the spreadsheet to my parents. “This is the truth,” I said, and slid it across the table. “I don’t want it back. I want it acknowledged.”

My mother’s face went white. “You kept… records?”

“I kept my sanity,” I said.

My father nodded, not at the numbers, at me. “You gave because you thought no one else would,” he said. “That was our job. We were too in love with controlling you to do it.”

I didn’t clap. I did not hug. Verbal contrition is a first step, not a sentence. I left the spreadsheet with them. You should know what a daughter’s bones look like under a microscope if you insist on rearranging them.

Part IV — The Gate

Grace tried rage first. Then she tried pleading. Then she tried nothing, which sounded like the old days felt.

Two months after the engagement party, she called. “Daniel left,” she said, voice husked with what silk does when it’s been soaked and wrung. “He asked questions, and I ran out of answers.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it. Suffering doesn’t redeem sins, but it sometimes opens a window.

“He asked me why I never told him you built Mova,” she continued. “I said it wasn’t relevant. He said truth always is.”

She laughed then, a sound that hurt my teeth. “He kept asking me what I’d done with the advantages I had. I couldn’t think of anything that wasn’t a party.”

“Grace,” I said, and paused. This is where old habits would have written a check. This is where I would have paid for a therapist or a new apartment or a PR firm. This time, I said, “If you want my help, you’ll have to want my honesty, too.”

She stayed silent long enough for the call to threaten to drop.

“I do,” she whispered.

“Then listen,” I said. “You are not nothing without them. But you are not everything because of them, either. Pick a thing that isn’t glamorous. Finish it. Call me when you have.”

Two weeks later, she texted a photo of her hands dirty with dirt, a community garden plot in the background, a caption that said, “Week one. Tomatoes. I know it’s not impressive, but it’s not for show.”

I replied with a heart I didn’t have to pry out of my chest.

Part V — The Ending With No Ceremonies

This is the part where I tell you I forgave them, and our Sundays are loud and messy in the way families are on sitcoms. Some are. Some aren’t. Leo knows that Grandma’s house has rules that do not apply elsewhere. He knows that if anyone says “wait for scraps,” his mother turns into a judge with a gavel. He knows that his grandfather listens more than he speaks now, and that this is new.

A year after the party, my parents invited us for dinner. Their apartment is smaller than the house I grew up in. The table is pressed against a wall. They served spaghetti. I watched my mother ladle it in equal portions. She looked me in the eye as she did it, as if to say, This is the sacrament, isn’t it? The small equal things?

When she got to Leo’s plate, she hesitated. “More?” she asked.

“Yes, please,” he said, polite because I am raising a boy who will not confuse equality with entitlement.

She gave him seconds. No one clapped. The world did not change. But the map redrew itself in a line only we could see.

I left early that night. In the car, Michael asked, “Do you need anything?”

“Just this,” I said, and watched my hand on my knee, steady as if it belonged to someone who had always known where she was going.

Coda — If You’re Still In The House

If you are twenty-seven and the phone rings and the voice on the other end says, “We need you to be who you used to be,” hang up. If you are twenty-one with a suitcase on the porch and the sentence “Don’t come back” pressed into your spine, breathe. They meant don’t come back as the version we can control. Do not.

Make a ledger. Count the money. Count the hours. Count the plates that were filled and the floors that weren’t. Cancel one transfer. Let one crisis miss your inbox. Watch who survives. Watch who screams. You will learn what love is in the quiet that follows.

Then throw a dinner. Feed the children first, not because they are fragile, but because their blood sugar is not a morality tale. Feed yourself second, because your hands will stop shaking if you do it often enough. Feed your parents if you can. Tell them the table is rectangular now; there are sides; there are corners; there are rules. They can sit and eat or they can leave. Either way, you will do the dishes with a man who says nothing when you don’t need words.

At twenty-seven, my parents tried to control me again. They forgot who they raised in the furnace of their expectations. Not a prodigal, not a problem to be solved, not a ghost in their narrative.

A woman.

Who showed up, then stayed put.

Who reached for the handle of a door she feared and found it unlocked because she had stopped giving them the key.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

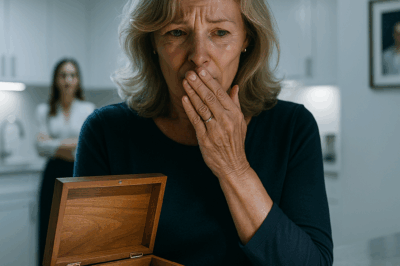

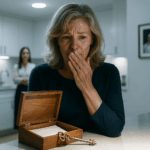

CH2. My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me

My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me My daughter thought she could take everything—my beach house, my…

CH2. My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed…

My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed… Part I —…

CH2. The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother

The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother Part I —…

CH2. After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not worth the trouble,” she said. I cleaned toilets for money. Monday, a detective found me: “Your real father in Germany spent millions searching for you. He left his automobile empire worth $2.1 billion -to claim it, you have 72 hours to your family’s darkest secret”

After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not…

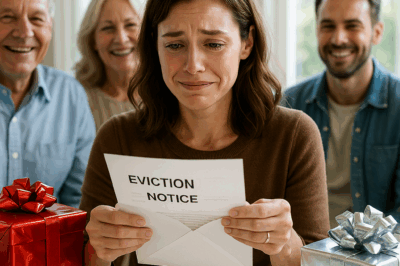

CH2. On My Birthday, My Family Gave Me A ‘Special’ Present. When I Opened It, It Was an Eviction Notice for My Own House. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding Day…

My Family Gave Me an Eviction Notice on My Birthday. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding…

CH2. My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed…

My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent It to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed… …

End of content

No more pages to load