After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not worth the trouble,” she said. I cleaned toilets for money. Monday, a detective found me: “Your real father in Germany spent millions searching for you. He left his automobile empire worth $2.1 billion — to claim it, you have 72 hours to your family’s darkest secret”

Part I — The Door That Didn’t Close, It Locked

I was sixteen when my mother decided my existence cost her too much.

Greg had been in our lives a year, just long enough for his cologne to outweigh the smell of the curry my mother used to make on Sundays. He smiled like a deacon, shook hands like a salesman, and spoke to me like I was an inconvenience he’d inherited in a merger.

The night she chose him, the electric meter ticked like a heart we couldn’t afford. She turned my suitcase toward the door herself. “He’s not worth the trouble,” she said, and I don’t know to this day whether she meant me or my dead father.

You can survive anything if you decide it’s not going to be the last thing you do.

I cleaned toilets. Slept behind diners. Learned which dumpsters received bread before the mold learned my name. I stacked cash into an envelope that never grew heavy enough to change anything. People handed me kindness like a weather forecast—useful for a day, then gone.

On nights I slept in the bus station, I would make up stories about the father my mother claimed had abandoned us. In some I hated him. In most, I forgave him because it was easier to survive when you pretended someone was still looking for you.

No one was. Not then.

Part II — Monday, Bleach, and a Business Card

The mop water had gone gray when the detective found me.

He held his own handkerchief to his face like the smell was an enemy he respected. He didn’t stand in the doorway like a tourist; he walked in. “Ava,” he said, and my name sounded strange coming from someone who hadn’t used it to ask me to move out of the way.

“Who are you?” I asked, because people who look like you have news, and it’s never the kind that lands softly.

“Detective Haroon Malik,” he said, offering a card I couldn’t wipe my hands clean enough to take. “I work with a firm that vets international estates.” He set the card on the counter, away from bleach and disbelief. “Your… your real father in Germany spent millions searching for you. He died last week.”

My first thought was cruel: Good—the story finally ends. Then he put a folder on the steel counter between us like a relayed baton. Inside, a DNA report that carried my cheek cells to a name I’d never been allowed to say out loud. Johannes Reindl, CEO of Reindl Motorwerke, an automotive firm whose posters had hung on the walls of men who would never drive one.

He turned more pages. A birth certificate with another man’s name crossed out and corrected by hand in a scrawl I recognized too late: my mother’s. Letters sent to our old address and returned. Checks cashed for a “trust in the child’s name” and deposited into an account that wasn’t mine. A photocopy of a custody petition stamped rejected with a note—mother reports child deceased in an accident; father withdraws to avoid harassment.

Detective Malik’s next line didn’t belong in any universe I recognized. “Mr. Reindl left you everything. The board is prepared to seat you as controlling shareholder. But there is a stipulation. To claim it, you have seventy-two hours to uncover your family’s darkest secret.” He rapped the file lightly. “Prove it. Hand it to the board’s counsel. If you miss the window, the trust defaults to an automotive foundation.”

“You’re joking,” I said.

He shook his head. “Johannes was a precise man. His instructions are… unusual. But he didn’t spend years searching for a ghost to leave a mess.”

“What secret?” I asked.

“You tell me,” he said. “You have until Thursday noon. There’s a ticket in here. Frankfurt tonight. We’ll meet at the consulate at nine tomorrow. We can buy you clothes on the way.”

I pressed the edge of the counter until it bit my palm. For the first time since I’d been sixteen, I wasn’t staring at a door that had been shut; I was staring at one that, if I kicked hard enough, might open.

“I need to see someone first,” I said.

He didn’t ask who. “You have six hours.”

Part III — The House That Upgraded Without Me

My mother answered the door in silk.

The house had moved neighborhoods. The plants were trimmed into obedience. Art hung on the walls that had never known our old damp apartment. The smell wasn’t cooking; it was a scent machine pumping cedar and money through vents that hadn’t carried my name in years.

Her eyes tried to inventory me and failed. “Ava,” she said, and my name sounded like a coin flipped to see which side it would buy. “We were—uh—just leaving.”

“Where’s Greg?” I asked.

“Not now,” she said, because she thinks later is a synonym for never.

He emerged from the hallway, belly leading, grin tired. Age had not improved his morals; it had only made them more comfortable. “Well, well,” he said. “Look who the wind couldn’t even bother to blow back properly.”

I set the file on the console table like an altar offering. “Where did all this come from?”

“Hard work,” he said. “Opportunity.”

“Forgery,” I said. “Larceny.”

My mother’s hand fluttered to her throat. People always touch their throats when the truth arrives like a hand at their neck. “Ava, you are being dramatic.”

I opened the folder to the birth certificate. “Whose handwriting is that crossing out my father’s name?”

“Don’t you dare—”

“Johannes came back,” I said softly. Her face told me the part of the story she had buried in a garden she never watered. “He came back when I was seven.”

“He would have taken everything,” she hissed. “He would have—”

“He tried to take me,” I said, and the past tense dropped between us like glass. “And you told him I was dead.”

She pressed her palms to the edge of the table until the wood squealed. Greg looked from one face to the other, calculating which ship still floated.

“Why the empire?” I asked. “Why the cars?”

Greg recovered first. “You can’t prove anything.”

Detective Malik stepped from behind the doorframe where he’d been impolitely patient. “She can,” he said mildly. “And so can a forensic auditor.”

Greg blanched. “You brought a cop—”

“Private investigator,” Malik corrected. “I prefer the food where I work.”

I had spent too long wanting her to look at me like I was her daughter. The closest she came now was to look at me like I was a mirror. “He abandoned us,” she said, one last attempt to rewrite history in a font only she could read.

“He wrote letters until his hand failed,” I said. “He sent money until you stopped cashing checks so you could claim moral advantage. He spent millions trying to find a child he was told had no heartbeat. He built a clause into his will that said I needed to bring the dark into light before I could touch a cent of his.”

Her mouth opened. Closed. “If you want to arrest us, arrest us. It won’t change what he did to me.”

“I’m not a prosecutor,” Malik said. “But I know papers that will enjoy meeting one.”

I didn’t need her confession. I needed proof—and proof was a thing people like Greg leave everywhere because they believe they’re too clever to need to hide.

“Your study,” I said. “Third drawer down. Left side.”

She flinched because everyone’s secrets are in the third left-hand drawer. I walked past her through a house that had been paid for with a dead man’s devotion and a living man’s theft. The drawer squealed. A blue folder slept where I knew it would. Inside: a notarized statement from twenty years ago, attesting that the child known as Ava had died in an accident. Signed, because tragedy forgives everything, by a doctor I recognized from when my mother made me wait in the hallway, and by my mother herself.

I snapped photos. Texted them to an address the detective had given me. The cloud accepted them like rain. The timer I’d set the second I’d taken the file from Malik’s hands counted down with the serenity of a guillotine.

“Seventy-two hours,” I said aloud, more to myself than to them. My mother’s face flared with comprehension.

“What happens then?”

“Germany,” I said.

“You think you have a family there,” she sneered, but fear had replaced venom. “You think they’ll just… welcome you because your blood—”

“I don’t think anyone owes me anything,” I said. “But I’m done letting you owe me my own life.”

Greg lunged. I had been waiting for that since I was sixteen. I stepped back. Malik moved like water in a glass being tipped. He pinned Greg without touching him; some men carry law in their stance.

“Try again,” Malik murmured. “See if a timer works as handcuffs too.”

My mother spoke my name like a spell that had stopped working. “Ava, listen to me. He left you. I raised you.”

“You locked me out,” I said. “I raised myself.”

Part IV — Frankfurt, Grief, and a Boardroom With Too Much Glass

The consulate smelled like paper and distrust. Men in suits who smiled with their lips more than their eyes led us through hallways that all thought they were important. At nine precisely, a woman in a blazer sharp enough to slice an apple greeted me with a handshake engineered to convey firmness and welcome in equal measure.

“I’m Katharina Baum,” she said. “Board counsel. I knew your father. I’m sorry for your loss—even if you’re just beginning to feel what that means.”

“Thank you,” I said, because there are rituals even for orphaned adults. She handed me coffee and an agenda. “This way.”

The boardroom arced around a table that cost more than the restaurant kitchen where I’d mopped my reflection off tile. On one wall, a photo of a younger Johannes in a brown suit looking at a prototype metal body like it was both a car and a prayer. Next to it, a childish drawing—stick figures with a large blue rectangle I realized was a vehicle with our family inside. My name had been scrawled in block letters I remembered writing. He had framed a ghost’s drawing and put it in the room where he made the decisions that changed other people’s lives.

“Ms. Reindl,” said a man with a haircut engineered to reassure shareholders. “We’re deeply sorry for your absence.” The Freudian slip earned a blink from Katharina. He cleared his throat. “For your loss. We have to move quickly. The will stipulates a seventy-two-hour window for the heir to prove… certain facts.”

“You mean to confirm a lie,” I said, and slid the printed affidavit across the table. “My mother reported me dead to prevent him from getting custody.”

My phone thrummed against the wood: the digital vault releasing the recorded phone calls Malik had obtained, the wire transfers from Johannes flagged as “child trust” routing into an account Greg had declared on his taxes as a “windfall.” The bank had stamped it. The accountant had smoothed it. Everyone had eaten.

A board member with eyes the color of litigation scanned the document, then lifted his gaze. “This may make criminal charges in your country. Are you prepared for that?”

“Yes,” I said. “I’ve lived with a sentence for years.”

Another board member—a woman who looked like she had built herself from scratch and enjoyed the friction—leaned in. “The will also stipulates you must set the record to rights publicly. Not press. Not scandal. A statement of record. He believed truth belongs in the sunlight.”

I breathed in, out. Johannes hadn’t left me seventy-two hours to punish the people who had punished me. He had left me seventy-two hours to put my name back where it never should have been erased: alive.

“I’ll make the statement,” I said. “I want to do it where he started.”

“Stuttgart,” Katharina said, and smiled like a woman who recognizes the precise tilt of a soul that has decided its axis.

Part V — Statement

Outside the original Reindl workshop, cameras blinked like insects. The smell of warm oil that had soaked into the brick outlived the men who’d rubbed it in. I stood at a podium that had known speeches made by men who didn’t cry when they were supposed to.

“My name is Ava,” I began, and I made my mouth pronounce it the way my mother had when she sang to me the German lullabies she claimed were the last good thing he left us. I told them what had happened without burning anyone. The papers could do that. I preferred arson to occur in court, not in press.

“My father did not abandon me,” I said. “He was lied to. He spent the rest of his life trying to find a daughter he was told had died. He left me a task: bring it all into sunlight. I have done that.”

A breeze shifted banners. Somewhere in my chest, a pressure valve finally acknowledged that it was designed to be turned.

“The empire he built—this company—cannot be inherited like furniture. It must be earned. I don’t intend to replace a man whose genius I cannot replicate. I intend to steward what he left and change what needs changing. Reindl will build differently. We will pay our apprentices beyond subsistence and teach them beyond bolts. We will audit our supply chains for labor worth honoring, not exploiting. We will electrify not because the PR is clean but because the air children breathe deserves our engineering. We will put a phoenix on every steering wheel—not because I escaped, but because we will not burn our workers to thrive.”

The reporters stopped taking notes halfway through. They looked not at their screens, but at me, and in their faces I saw something that looks a lot like hope when it holds a wrench.

At the back, a janitor in blue coveralls clapped first. Katharina joined. The board’s applause sounded like budgets adjusting.

When it ended, I walked into the workshop alone. The brown suit in the photograph had been replaced by my reflection in glass. I touched the child drawing through the frame. The blue rectangle looked like a box she had been told she could not leave. I have learned you can draw your way out.

Part VI — Reckonings That Don’t Need a Microphone

The police took Greg’s statement in a room that could smell your fear and tell you what brand it was. He asked for a lawyer that could rival a board counsel’s haircut. People with a certain kind of confidence forget that courtrooms are designed for people who relish paper. Malik watched like a man who had seen this film before and preferred its pacing to almost any other genre.

My mother’s arraignment happened quietly. The judge didn’t scold her for long. That would be for later, in sentences measured not only in months but in the kind of labor that humbles your nails. I did not attend. There are performances you don’t reward.

She called once from the women’s wing. “You got what you wanted,” she said.

“No,” I said. “He got what he wanted. I just stopped standing in the way.”

“What about what I wanted?” she asked, and for a second I saw the girl she had been in a country not her own with a baby and a man who worked too many hours to write anything but checks. “I wanted a life that didn’t punish me for being poor.”

“So you punished me instead,” I said. “And him.”

“I did what I had to do,” she said, and if there is any phrase that should come with warning labels, that is it.

“No,” I said. “You did what you chose. So did I.”

I hung up. It is possible to love the person who braided your hair and refuse to light her way back with your own body.

Part VII — Engine, Heart

Assume power like you’re holding a live wire.

I didn’t “take over.” I learned. I spent mornings in meetings where older men called me Ms. Reindl until the title didn’t itch, then my afternoons in the prototype room with women and men who taught me the smell of a gear that’s been polished into forgetting it had teeth. I learned the names of the people who delivered the sandwiches. I learned that if you change the minimum wage in your factory, the town square gets new benches.

At night I took a coffee down to the design floor where the lights make everything look like a dream you could hold. In the corner, I had them install a small framed image: a phoenix in relief. Under it, in paint so small you needed to want to read it, while rising, do not set anyone on fire.

The board voted to approve an apprenticeship program for kids like the one I had been: people who can take things apart and remember where everything belongs. We partnered with a shelter. We built a tool library. We added therapy hours to our benefits. A journalist asked why an automaker was doing social work.

“Because every engine has a heart,” I said. “And if you ignore either, you stall.”

I met the workers outside Stuttgart who had labored thirty years for a pension they weren’t yet sure they would live to spend. I shook the hand of a young woman in Sindelfingen who could diagnose a rattle with her eyes closed and asked if she would be our lead on a new line. She said she had to check with her mother about childcare.

At a dealer event, a man who had nearly bought my house for my brother shook my hand and said, “You didn’t destroy him. You just refused to be his alibi.” I told him I couldn’t have done either without a detective who showed up in a gas station bathroom and a lawyer who wore her hair like a reason to sit up straight.

The phoenix emblem went on every steering wheel, a small grief I could touch with my thumb every time I drove out of a city I had once slept in by necessity rather than choice.

Part VIII — Seventy-Two Hours and the Rest of Your Life

In the end, the seventy-two hours Johannes had offered me weren’t a trick. They were mercy. They forced me to choose speed over rumination, sunlight over the romance of secrets. They taught me that time isn’t what heals; it’s what proves whether you’ve moved.

On the last day of the window, at one minute to noon, I stood again in the boardroom with the blue drawing behind me and watched the security time stamp flip to 12:00 on the wall.

Katharina smiled. “Done,” she said. “Binding.”

“What now?” I asked.

“You take the afternoon off,” she said. “You buy shoes without looking at the price. You cry or don’t. Tomorrow, you come back and piss someone off with a budget line that says childcare on site.”

I laughed and surprised the room. I signed a document. There was no ribbon cutting. There was just an engine turning over, somewhere—metal, then fire, then motion.

Two months later, I flew back to the city where I used to hunch my shoulders against rain. The bus station still smelled like coffee and heartbreak. I walked past the restaurant where I had bleached the corners no one else bothered to see. Malik met me at the curb.

“You look tired,” he said, which is how men like him say you look alive.

“I am,” I said. “Thank you.”

“For what?” he asked.

“For believing I wasn’t going to throw this back in your face and call it a mistake.”

He shrugged. “I don’t work for people who do. Also, your company sent me a car.”

I snorted. “Occupational hazard.”

He handed me a photograph. Johannes and me, the only photo of us I hadn’t known existed—someone had caught us at a street fair the year before I was declared dead to him. I am on his shoulders, laughing, one hand tangling his hair, the other pointing at something out of frame like the future had just walked by. He looks up at me like he’d seen a miracle he shouldn’t touch and decided to anyway.

“I thought you should have this,” Malik said. “The dark secret was never whether he loved you. It was what people will do to a light they can’t control.”

I slipped the photograph into my wallet behind my ID, under my company card. I slid my thumb along the edge until it warmed.

On the flight back, the clouds looked like new cities. I signed off on an R&D budget line for a team building an electric truck that can carry more than possibility. I approved a scholarship name that made a PR guy cry. I made a note to call the man at the bank who had turned pale in the notary office and tell him to make his compliance training more aggressive.

And then I did the most decadent thing a person who has starved ever does: I stopped counting.

When the car met me at the airport, the driver showed me how to fold the back seats down to accommodate the bikes I had suddenly decided I owned. He pointed to the steering wheel. The phoenix gleamed in the late light.

“You did that,” he said.

“We did that,” I said. He grinned in the rearview.

At home, the house in Stuttgart already smelled like tea because someone had switched the lights on before I landed and that someone was me, that girl who used to sleep in bus stations, who used to bleach floors, who used to pray to a mother who refused to be a god.

I set Johannes’s photo on the mantel. I put the blue drawing next to it, framed in something cheap because some things shouldn’t get too fancy. I lit a candle and told the flame, as if it needed reminding, that I was here now—not because I had won, but because I had refused to let a lie write me out of a life that knew my name.

People ask me what I did with the first money that was truly mine.

I bought a bed that didn’t squeak and stocked the fridge with food that didn’t expire, yes. I sent a check to the shelter that had ignored my tendency to flinch when doors close loudly. I paid a therapist more than I thought I could afford to help me stop expecting every good thing to vanish between a file folder and a phone call.

But the most extravagant thing I bought was time. Seventy-two hours taught me how to hold it without apology.

The darkest secret is out. The empire is loud. My mother will learn to say my name without expecting me to answer. My father will stop being a rumor whispered in German and become a man whose grief I carry like something you respect and put down sometimes to sleep.

I drive with my hand at the twelve o’clock position and my thumb on the phoenix. The engine hums. The road opens. The mirrors show me where I’ve been without insisting I reverse.

It turns out you can be forced into the street at sixteen and arrive at a boardroom at twenty-two without letting either one define what kind of person you are. The trick is not exceptionalism. It is paperwork and mercy. It is knowing when to mop and when to make someone else sweep up what they spilled.

The seventy-two hours ended. I didn’t.

The end.

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

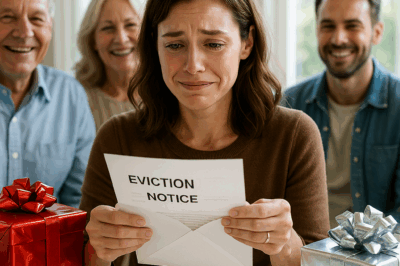

CH2. On My Birthday, My Family Gave Me A ‘Special’ Present. When I Opened It, It Was an Eviction Notice for My Own House. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding Day…

My Family Gave Me an Eviction Notice on My Birthday. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding…

CH2. My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed…

My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent It to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed… …

CH2. At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake

At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake Part I — The Invitation With a…

CH2. My Family Told My Sister’s Kids To Eat First And Told My Kids To Wait To Share The Crumbs.

My Family Told My Sister’s Kids To Eat First And Told My Kids To Wait To Share The Crumbs …

CH2. My Mom Handed Me A Glass Of Red Wine With A Strange Smile At My Engagement Party It Smelled Off I Swapped It With My Sister Thirty Minutes Later She Collapsed And..

My Mom Handed Me A Glass Of Red Wine With A Strange Smile At My Engagement Party. It Smelled Off….

CH2. Half a Heart, Whole Courage – Rita’s Miracle Journey

On Valentine’s Day, while the world celebrated love, our little girl was fighting for her life. Rita underwent her second…

End of content

No more pages to load