1943: American Pilots Captured Japanese Betty Bomber – Called It A Flying Death Trap

The heat on the Clark Field tarmac felt less like weather and more like punishment.

The noon sun hung straight overhead, turning every sheet of aluminum into a mirror and every patch of concrete into a griddle. The air wavered. Sweat found every seam in a uniform and went to work.

Major Frank T. McCoy wiped his forehead with the back of his hand and squinted across the shimmering runway at the aircraft waiting for him.

It sat alone, just off the main strip. No bullet holes. No missing control surfaces. No blistered paint or crumpled spars. Just a long, faintly green cigar of an airplane, its wings casting a hard black shadow on the concrete.

Tail number 763-12.

A Mitsubishi G4M.

A “Betty.”

He’d seen plenty of Japanese wreckage in three years of war. He’d crawled through jungle to reach burned-out Zero fuselages, brushed ants off of mangled Nakajima tail assemblies, and carefully pried identification plates from twisted engine mounts. He’d catalogued components on coral atolls in the Solomons and in steaming New Guinea ravines, cursing mosquitos and mud and the smell of burned fabric.

But he had never had this.

A complete enemy bomber.

Standing there in the white glare of a Luzon afternoon, he could have imagined it had just rolled off a Japanese assembly line and taxied into place for him.

“Hell of a thing, isn’t she?”

The voice came from behind him. McCoy turned to see a young captain, sleeves rolled, flight cap tilted back, a cigarette pasted to his lower lip.

“Sure is,” McCoy said. “Where’d you boys steal it?”

The captain grinned. “Found her in the bushes, Major. When we took the field, the Japs were in such a hurry to get out they just left her. Some gas in the tanks, logbooks in the cockpit. Even the bomb racks are still in place. Like they meant to come back and forgot.”

McCoy let his gaze trace the curve of the fuselage. The G4M was bigger than the photos made it look—nearly twenty meters from nose to tail, with a wingspan about twenty-five meters. Not a lumbering four-engine beast like a B-17, but no toy either. Just two engines, one on each wing, and that long, slender body.

He’d heard the names the fighter boys used for it.

Flying Cigar. Flying Zippo. One-shot Lighter.

Names chosen by men who’d watched these machines light up the sky like Roman candles.

He stepped closer and put a hand to the skin of the wing. Hot. You could have fried an egg on it. The paint felt thin under his palm.

“Mind if I take a look?” he asked.

“That’s why they flew you up, sir,” the captain said. “She’s all yours. Just don’t start her up and fly her back to Tokyo, okay? The Air Corps will get jealous.”

McCoy let the joke roll past him. His mind was already mapping out what he wanted to see first.

The engines could wait. The gun installations, the bomb bay—those too.

The thing he most wanted to see lay inside the wings.

He climbed up onto the wing root using the built-in footholds, boot soles slipping slightly on the warm metal. From up there, the Betty’s fuselage stretched ahead of him like the back of some enormous fish. The cockpit canopy glared in the sun. Far out at the tip, the wing tapered to a point that would have looked more at home on a fighter.

He found the inspection panel just outboard of the engine nacelle. His fingers worked the simple latch, expecting resistance, some sign of sabotage or scuttling.

The panel opened easily.

No lock. No complicating mechanism. Just a thin aluminum cover and, beneath it, the heart of the aircraft’s vulnerability.

He froze.

There, pressed up against the very skin of the wing, were fuel cells—soft-sided, pale, absolutely naked. No rubber layers. No protective plating. No fire suppression plumbing. No self-sealing coating at all.

Just a couple of millimeters of aluminum between thousands of liters of high-octane fuel and the outside world.

He leaned in, touched the edge of the tank. It flexed gently under his fingers.

He moved to the next panel. Same story. And the next. Every access hatch he opened revealed the same shocking absence.

“Jesus,” he whispered.

He’d seen what .50 caliber rounds did to these things in the air. The fighters’ gun camera footage showed Bettys that went from unharmed to burning comets in a heartbeat. He had assumed—everyone had assumed—that somewhere inside those wings was some kind of protection that had failed under certain conditions.

There wasn’t.

There had never been.

This wasn’t field modification. This wasn’t a last-ditch, late-war shortcut. This was design.

He straightened and looked down the long wing, feeling as if someone had quietly handed him the answer key to a puzzle he’d been staring at for three years.

Of course it burned, he thought. Of course they all burned.

Two floors below his feet, under a different sky, another man had stared at numbers on paper and made a decision that brought them both to this moment.

Tokyo, 1937.

The office wasn’t much. Bare walls. A wooden desk scarred by code numbers and the occasional cigarette burn. A single oscillating fan. Outside the window, the city already hummed with a tension that had nothing to do with the weather. China was on fire. Europe was wobbling. The Navy’s eyes were fixed far beyond Japan’s shoreline.

Inside, Kiro Honjo sat at his desk and slowly exhaled.

The specification sheet in front of him looked simple enough.

Land-based attack bomber.

Combat radius: 2,400 kilometers, with 800 kilograms of bombs.

Maximum speed: 400 kilometers per hour.

Crew: seven.

He flipped the page. The rest was details—bomb load configurations, defensive armament, service ceiling, takeoff and landing distances.

He’d been designing aircraft for long enough to know that specifications flowed from desires, and desires flowed from fears.

The admirals feared distance.

The Pacific, from their perspective, was not a shield. It was a bridge. Or could be, if they could build the right machines.

They wanted a bomber that could leave the home islands, reach an enemy atolls or fleets or ports thousands of kilometers away, strike, and return.

No existing aircraft anywhere did that.

American bombers like the B-17 Flying Fortress emphasized defensive guns, armor, and robust structures. They could soak up punishment. They brought their crews home.

British designs weighed heavily toward payload—how many bombs could be crammed into a bay, how much destruction could be delivered in one raid. Range was important, but not the organizing principle. Europe’s distances were measured in hundreds of miles.

The Pacific’s were measured in thousands.

Honjo took a pencil and began jotting numbers in the margins.

Fuel consumption at cruise, power settings, densities of materials, energy content of gasoline. The numbers resolved slowly into a picture.

If he did what Western designers were doing—if he built in self-sealing fuel tanks, if he made concessions to armor around the cockpit, if he added redundant systems and extra structure—he could not meet the range requirement.

It wasn’t a question of cleverness. It was physics.

The bomber would need to carry nearly its own empty weight in fuel—some 4,800 liters worth, over 3,400 kilograms, sloshing in its wings and fuselage. Every kilogram he added for protection would subtract directly from range or payload.

Self-sealing fuel tanks were marvels of chemical engineering. Layers of rubber and treated fabric that swelled when in contact with fuel, closing bullet holes and preventing leaks. They dramatically increased survivability when a tank was damaged.

They were also heavy.

Fully implemented, a self-sealing system for the bomber described on his sheet would add roughly 500 kilograms. To keep the aircraft within takeoff limits, he would have to remove around 800 liters of fuel to compensate.

800 liters of fuel meant about 1,000 kilometers of lost combat radius.

He stared at that number.

That kilometer figure was not an abstraction. On the big wall map at Navy headquarters, 1,000 kilometers was the difference between being able to hit Rabaul or not. Between striking Darwin from Timor or not. Between reaching the Philippines from Formosa or not.

He took a blank sheet and wrote two words at the top.

Protection vs. Range.

Under protection, he listed self-sealing tanks, armor around the cockpit and engines, more robust structural members. Under range, he just wrote one thing.

Fuel.

The sliding scale was simple. More protection, less fuel. More fuel, less protection. Somewhere in between was a compromise.

The specifications on his desk did not leave much room in between.

He closed his eyes for a moment. In those days he still thought in terms of machines, not men. Engineers are trained to see forces, weights, stresses, flows. The human beings who sit in the machines are often numbers in the margins.

He imagined the admiralty’s reaction if he came back and said: we can give you a bomber that can fly to your targets, but only if we accept that when it is hit, it will burn easily.

He also imagined their reaction if he said: we can give you a bomber that is hard to shoot down, but it can only reach half the places you want it to reach.

He knew the answer before he unscrewed the pencil cap.

Japan’s war plan in 1937 was a gambler’s plan. Land grabs in Southeast Asia. Bold strikes. Long odds.

Gamblers did not buy insurance.

He wrote a circle around the word “Fuel” and underlined range.

Then he drew a line diagonally through “self-sealing.”

And he made a quiet choice that would, in the years to come, turn the Pacific skies into a funeral pyre for thousands of his countrymen.

The G4M, the bomber he was about to design, would sacrifice protection for reach. The fuel tanks would be unarmored, unsealed. Every gram of saved weight would be poured back into range and speed.

They would build a bomber that could go farther than anything in the world.

And hope that it had no need of luck when it got there.

The first prototype flew in October 1939.

On the concrete apron at the airfield, officers in stiff uniforms and enlisted men in white caps watched the green-painted aircraft roar down the runway and lift smoothly into the gray autumn sky.

Its test results were everything the Navy had wanted and more.

Lightly loaded, it could cruise for over 6,000 kilometers. Its top speed exceeded 420 kilometers per hour, better than the spec. It handled well enough for trained pilots. It could carry its 800-kilogram bomb load at the required ranges with a margin for higher fuel consumption.

On paper and in demonstration flights, it was triumphant. A small group of designers, in a country just emerging from artisanal aircraft construction, had built a world-class long-range bomber.

Production orders followed fast.

By April 1941, G4Ms were entering front-line service.

The first crews who climbed the ladders into those long fuselages noticed what wasn’t there as much as what was.

A pilot ran his hand along the wing opening and tapped the fuel cells with his knuckles, listening to the hollow thud. A tail gunner ran a finger along the thin walls near his position and could almost flex the metal.

Word passed between them in mess halls and barracks and on the line.

It’s fast, they said.

It goes far.

It burns.

But they did not write that last part in reports.

You did not question specifications.

You flew what you were given.

The war that would test Honjo’s calculation did not take long to arrive.

In the first week of December 1941, as Japanese carrier crews prepared to hit Pearl Harbor, Japanese land-based air groups on Formosa readied their own targets.

One of them was Clark Field in the Philippines.

On the morning of December 8th (December 7th on the other side of the International Date Line), 82 G4M bombers and 26 older G3Ms took off from their bases in Formosa and droned southward over the sea, loaded with bombs.

Clark Field lay some 460 miles away.

American doctrine did not expect land-based bombers to hit them from that range. B-17s could not have made the reverse run from the Philippines to Formosa and back with meaningful loads. But the Bettys were not B-17s.

Shortly after noon, at 20,000 feet, the Japanese bomber formation arrived over Clark.

On the ground, American crews had pulled aircraft into neat formations on the apron. Fighters were being refueled. Bombers were parked wingtip-to-wingtip.

The sirens, when they sounded, sounded too late.

From their cockpits, Betty pilots rolled their sleek aircraft into bomber runs over a target that presented all the soft, allure of a buffet line. Bomb bay doors opened. Bombs fell. Explosions walked across the field.

Of the 17 B-17 Flying Fortresses present at Clark that day, 12 were destroyed on the ground. Most of the P-40 Warhawks were wrecked. Hangars burned. Fuel tanks burned. Men died in quick, ugly clusters, buried under collapsing roofs or shredded by shrapnel as they ran.

In forty-five minutes, American air power in the Philippines was effectively gutted.

The Bettys turned north and went home. They had flown from beyond the range of American bombers, struck hard, and escaped untouched. No fighters had challenged them. No flak batteries had found their range.

The aircraft that some crews privately called “flying lighters” in mockery had, in its first real combat, performed like a long-range scalpel.

Two days later, on December 10th, the G4M delivered a different shock, one that came not from statistics but from the sinking feeling in the Prime Minister’s stomach.

British Force Z—battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse, supported by destroyers—steamed off the coast of Malaya, attempting to intercept Japanese invasion convoys. They were formidable ships, veterans still smelling of fresh paint and wartime modifications.

They had no air cover.

Twenty-six G4Ms found them in open water.

The bomber crews came in low, torpedo fins slicing white lines in the dark sea. British gunners fired desperately. 5-inch shells thundered. Machine guns cut arcs through spray. The big ships maneuvered, but torpedoes still found them, slamming into armor belts and soft underbellies.

In less than two hours, both capital ships rolled and sank, taking 841 sailors with them. It was the first time in history that modern, actively maneuvering battleships at sea had been sunk solely by aerial attack.

Winston Churchill would later write that in all the war, no single report had hit him so hard.

To the men in the cockpits of the Bettys that returned to their airfields, banking low over palm trees before flaring to land, the lesson was clear.

Their bomber, fragile as it might be to bullets, could kill giants if it arrived unopposed.

In the first months of the Pacific War, it arrived unopposed a lot.

From bases in Timor, G4Ms flew 1,500 miles to hammer Darwin, Australia, in February 1942, the same day Japanese forces smashed into Singapore. The long shadow of their wings fell on Allied shipping in the harbor as bombs whistled down.

From Rabaul, they flew daily raids on Port Moresby, crossing 600 miles of jungle and mountains. Allied defenders couldn’t strike their bases; Rabaul was out of range.

The Betty’s extraordinary reach made far-flung outposts feel exposed in a way no one had fully anticipated.

For a time, the bomber that had been built by sacrificing protection looked like a stroke of genius.

But in war, every advantage is conditional.

And every unarmored fuel tank waits for its bullet.

The first clues that the Pacific air war was changing arrived on the morning of August 8th, 1942, as a formation of twenty-three G4Ms from the 4th Air Group lifted out of Rabaul’s hot, sticky air and headed southeast toward a tiny speck of land called Guadalcanal.

It was a route they knew. Six hundred miles of open water, then the jagged teeth of the Solomons on the horizon. They’d flown similar raids dozens of times.

Down below, Japanese troops were trying to hold an airstrip on Guadalcanal against newly landed American Marines. High command in Rabaul ordered: suppress the airfield. Keep the Americans grounded. Hold the island.

The Betty crews did as they were told, lining up in their tight boxes, engines throbbing in comfortable rhythm. In the lead bomber, the pilot glanced at his fuel gauges, double-checked the course, and thought about the letters he’d written the night before.

They expected flak. They expected a handful of fighters.

They did not expect Marian Carl.

High above Henderson Field, Captain Marian Carl of the United States Marine Corps slid his F4F Wildcat into position and squinted through his windscreen.

Radar had given them warning. Word had come from coastwatchers—independent observers on nearby islands—that “many bombers” had lifted from Rabaul. Pilots had scrambled. Now Carl and his division hung above the inbound Bettys with the sun at their backs.

“We came at them from high and ahead,” he would say later. “The moment our rounds hit their wings, they just exploded.”

He rolled in, stomach lifting, nose down, the Betty formation growing in his gunsight. The fat, cigar-like fuselages and narrow wings filled the center of his view.

He pressed the trigger.

.50 caliber rounds stitched across the nearest bomber’s wing.

For a fraction of a second, nothing happened. Then the wing blossomed into fire. Flames sprinted across the surface as if racing to beat each other to the fuselage. The bomber lurched, rolled, and fell, a comet trailing orange.

Carl snapped to the next target. Same thing. A few seconds of fire, a wing hit, and then the horrifically familiar bloom.

Around him, other Wildcats tore into the formation. The sky became a chaos of tracer lines and twisting shapes. One Betty after another burst into flame.

Of the twenty-three bombers that had left Rabaul, eighteen died over the waters near Savo Island that day. Approximately a hundred and twenty men went into the sea, many still strapped into burning cockpits and gun positions.

Five G4Ms made it back to base, some with holes in their skins, some with crew missing.

Their reports were variations on a theme: the Americans came from above and ahead; their fire started in the wings; the fires were immediate and inescapable.

Within weeks, American fighter squadrons across the theater repeated the story.

Lieutenant James Swett, a Marine aviator who would eventually down seven Japanese aircraft in a single action, described the Betty without romance.

“The Betty was the easiest kill in the Pacific,” he recalled. “Hit the wing anywhere and it was over. The whole thing would light up like a torch.”

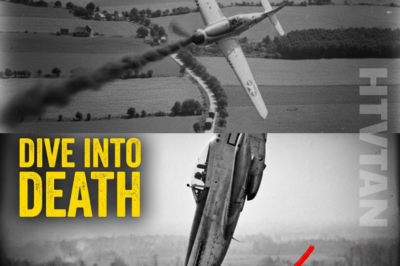

The bomber that had been an unstoppable, high-altitude terror over Clark and off Malaya was now a flying death trap when it had to pass through an American fighter screen.

The tactical roles had reversed. In 1941 and early 1942, Japanese Bettys had flown from invulnerable bases to strike forward Allied positions whose fighters and bombers lacked range.

By late 1942, it was American fighters operating from places like Henderson Field and Japanese bombers that had to cover long distances through contested airspace.

The Betty did not handle contest well.

Between August and October 1942, over Guadalcanal alone, more than a hundred G4Ms were shot down. Roughly seven hundred Japanese airmen died in those three months.

The math that had looked so clean on Honjo’s desk in Tokyo now reappeared as another kind of ledger—names on casualty lists, photographs on Buddhist altars at home.

But those numbers were still abstractions compared to what it meant to sit in one of those unprotected wings.

Lieutenant Fujio Yu of the Takao Air Group wrote to his family in October 1942.

His letter, found in a bundle after the war, was brittle with age when American translators read it. The ink had faded in places, but the words were still sharp.

We call our aircraft Hamaki, he wrote. The cigar.

Every mission, we joke about who will light up today, but it’s not really a joke.

Yesterday, Tanaka’s aircraft took a single hit during the bomb run. We watched it fall. The fire was visible from two kilometers away. Seven men. I knew every one of them.

He did not discuss design specifications or rubber layers or kilograms saved. He did not know the numbers that had dictated the shape of his fate.

He knew only that the thin skin between him and the sky also separated him from thousands of liters of gasoline.

Petty Officer Kawashima Hiroshi, a tail gunner, kept a diary on thin paper, writing in tight characters after each mission.

Third mission to Guadalcanal, he wrote once. Fourteen aircraft departed, nine returned. The Americans are everywhere now. We’re not flying bombers anymore. We’re flying coffins that happen to have wings.

In American bombers, B-17s and B-24s, crews spoke of their aircraft as rugged friends. Airplanes came home with engines shot out, with tails shredded, with holes in their wings big enough to crawl through. Self-sealing tanks dripped and swelled, stopping leaks. Armor plate behind seats deflected fragments. Men limped back, bandaged and shaken, to fly again.

In the G4M units, there was no such mythology.

You either came back untouched, or you didn’t come back at all.

There were no half measures. No limping survivals. No “we almost didn’t make it” stories—just mission debriefs where planes were either marked present or absent.

Some crews tried to improvise.

They scrounged rubber matting and hung it beneath the wing tanks. They stacked their flak vests in the wing roots, hoping the steel plates might catch a stray bullet. They draped spare blankets in the hope they might slow flaming fuel.

These modifications were talismans. The .50-caliber rounds didn’t notice them.

Lieutenant Commander Takahashi Kaichi, a respected formation leader, wrote a report in late 1942.

The G4M is operationally obsolete, he wrote. We cannot sustain these loss rates. Every mission is ending in death. We need protected aircraft or we need to stop flying.

The report went up the chain.

Industry could not meet the demand for new designs and new protections. The factories that might have been altered to build a redesigned bomber were already working beyond capacity building the old one.

The message came back down.

Keep flying.

In late 1942, at Buna in New Guinea, American ground forces overran an airstrip and found something they had not had before: relatively intact Japanese aircraft.

Technical Sergeant Robert Hayes was part of a recovery and analysis team that moved in behind the infantry. He walked up to a battered but largely complete Betty and, like McCoy would later, began opening panels.

He saw the same thing.

Nothing.

No self-sealing rubber. No armor. Just thin metal and the soft, vulnerable fuel cells pressed up against it.

Every American bomber Hayes had worked on had self-sealing tanks as standard. It was not an optional luxury; it was as essential as engines.

The idea that a major power’s primary land-based bomber could be in service, in heavy combat, without any such protection at all, shook him.

The reports compiled from Buna went back to higher headquarters and then across the ocean to stateside research labs.

What they described matched exactly what fighter pilots had been saying in more colorful terms.

The Betty didn’t just burn easily.

It was designed to.

Not intentionally in the sense of malice, but inevitably in the sense of physics.

Honjo’s decision in 1937 had come home.

One of the men killed by that decision never saw Buna or Guadalcanal. He spent most of his war in offices and on ships.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet and architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, believed in long stakes bets. He had pushed for the attack on Hawaii knowing it was a roll of the dice. He also knew, perhaps better than anyone, that Japan could not win a long war against the United States.

He said so in private.

In April 1943, he planned an inspection tour of frontline bases in the Solomons. His itinerary, as stiffly precise as any other staff officer’s schedule, was encoded and transmitted.

American codebreakers, who had been quietly building scaffolding around Japanese communications for months, read it.

They knew where he would be and when.

Seventeen P-38 Lightning fighters took off from Guadalcanal on April 18th with one purpose: to intersect the G4M carrying Yamamoto and shoot it down.

First Lieutenant Rex Barber was one of the men who found the bomber over Bougainville.

He approached from below and behind, closed into range, and fired.

“I aimed at the wing root and engine,” he recalled later. “I fired a long burst. The bomber immediately caught fire. I mean instantly. The whole wing was burning. There was zero possibility of survival.”

The Betty spiraled into the jungle.

Yamamoto and his staff died in the wreckage.

The unprotected fuel tanks that had given the G4M the range to strike Pearl Harbor on that distant December morning also ensured that the man who had ordered that strike could not be transported safely through contested skies.

Design choices did not care about rank.

They applied themselves equally to private and admiral.

By mid-1943, the survival rate for Betty crews flying the Rabaul–Guadalcanal run dropped below thirty percent for those who tried to complete a thirty-mission tour.

Most did not.

Japan’s pilot training pipeline, already under strain, began to crack. Pre-war and early-war bomber crews had received eighteen months of training. By 1943, replacement crews were being rushed through in six months or less.

They climbed into cockpits with fewer hours, less instrument experience, less formation practice.

They needed, more than ever, an aircraft that gave them a margin for error.

They had the opposite.

Warrant Officer Saito Masao, one of the few Betty pilots to survive the entire Guadalcanal campaign, looked back years later with a bitter clarity that old age sometimes allows.

“We knew,” he said. “Everyone knew. We were dying because someone decided our lives were worth less than a few hundred kilograms of weight savings. That’s what our range cost. Blood.”

That tradeoff played out again in one of the most desperate, almost surreal episodes of the late war.

By early 1945, Japanese planners, grasping for ways to slow the American advance on Okinawa and, eventually, the home islands, had embraced the concept of piloted suicide weapons—the Ohka (“Cherry Blossom”) rocket-powered glider bomb.

The idea was as simple as it was monstrous: a man in a tiny cockpit guided an explosive-laden projectile at very high speed into an enemy warship. To get the Ohka within range, it would be carried beneath the fuselage of a G4M.

On March 21st, 1945, eighteen Bettys took off carrying Ohkas slung under their bellies, headed toward the American fleet off Okinawa.

The weight and drag of the rocket bombs degraded the Betty’s performance dramatically. They climbed more slowly. They flew more sluggishly. Their already marginal ability to evade fighters was almost gone.

American radar picked up the formation sixty miles out. F6F Hellcats from carrier fighters intercepted long before the Bettys could reach release points.

One by one, the laden bombers were shot down. Their wings burned. The Ohkas, never ignited, tumbled away like monstrous toys and fell into the sea.

Not a single Betty survived to release its weapon.

137 bomber crew and 15 Ohka pilots died.

The mission was a tactical zero. Strategically, it was a grim joke: a weapon designed for one-way suicide attacks had been mounted on an aircraft so vulnerable it could not even deliver the suicide weapon to its destination.

Somewhere in a bunker in Tokyo, someone had to write a report about that.

Major McCoy did not know all these details as he crouched over the wing of 763-12 at Clark Field in January 1945. He knew some of them. He’d read intelligence summaries and after-action reports. He’d talked to fighter pilots who described how Bettys died. He’d seen enough to connect the dots.

But seeing it in person—the absolute nakedness of the fuel system—made it visceral.

He dropped back down from the wing, boots thudding on the concrete, and pulled off his cap, wiping his forehead again. The air smelled of hot fuel and dust and an acrid tang from a nearby burn pit.

He found a shade patch near the nose and pulled a small notebook from his pocket, flipping it open.

He wrote:

No self-sealing tanks anywhere in wing. No armor plate. Tanks just under 2 mm skin. Any hit = immediate fuel leak/fire. Weight savings estimate ~500 kg. Direct trade for fuel load/range.

He looked up at the bomber’s glazed nose, at the cockpit windows.

Somewhere, hundreds of times in the last four years, men had sat there, strapped into their seats, watching tracer fire crawl up their wings, and understood, in a moment longer than any engineer’s calculation, what that trade had meant.

McCoy continued his walk, moving to the fuselage, the tail, inspecting structure, gun emplacements, control runs. The more he saw, the clearer the pattern became.

Mitsubishi had built exactly what they had been asked to build.

The empty weight of the Betty—around 6,700 kilograms—was less than half that of an American B-17. The Flying Fortress was a brute at 16,000 kilograms empty, able to shrug off heavy damage and still lumber home. A great deal of that extra weight in the B-17 and B-24 was protection—armor around crew positions, self-sealing tanks, stronger structures.

The Japanese had made a different choice.

His final report would compare loss rates as best the analysts could calculate them. B-17 crews in the Pacific faced a combat loss rate of around three percent per mission. High, but survivable across a tour. The Betty’s loss rate in contested airspace exceeded fifteen percent per mission.

Five times higher.

He closed the notebook and slid it back into his pocket, feeling suddenly tired in a way that had nothing to do with the heat.

“Major?”

He turned. The young captain had returned, now with two canteens dangling from his hands. He tossed one to McCoy, who caught it reflexively.

“Thought you might need that,” the captain said. “What’s the verdict?”

McCoy took a long drink. The water was warm, but it tasted like salvation.

“The verdict,” he said slowly, “is that they built one hell of a long-range bomber. And they built it by turning it into a flying funeral pyre.”

The captain winced. “We always figured they were crazy bastards,” he said. “You hit ’em and they go up like they’re made of paper. But we didn’t know it was… on purpose.”

“It wasn’t suicide by design,” McCoy said. “Not exactly. They just decided range was worth more than human life. Designers don’t think they’re killing anybody when they shave weight. They think they’re making a better machine.”

He looked back at the bomber.

“Then the war comes along and tallies up the bill.”

When he filed his report weeks later, the language was drier. It spoke of comparative weights, performance, survivability. It concluded, in clinical terms, that the G4M’s designers had accepted catastrophic casualties as the price of unmatched range.

Someone back in Washington would read that and nod and maybe underline “catastrophic” with a red pencil.

It would be another entry in a war of decisions.

On August 19th, 1945, two white-painted G4M bombers, their green crosses visible from miles away, took off from Japan carrying the first Japanese surrender delegation to American-held territory at Ie Shima.

Their wings, once bearing red meatballs, now bore symbols of truce. Their fuselages, once loaded with bombs, now carried diplomats and officers in dark uniforms, their caps held in their laps, their faces lined.

American fighters flew escort—not to attack, but to protect. Orders had gone out: do not fire on the white Bettys.

Men on the ground watched as the bombers descended, lined up on the runway, and rolled to a stop.

It was a strange symmetry. The bomber that had helped open the American war in the Pacific by erasing Clark Field from the sky now helped to close it by delivering the men who would sign away the empire that had ordered that attack.

Of the 2,414 G4Ms built between 1940 and 1945, roughly half had been destroyed in combat. Others were lost to accidents, scrapped, or left to rot on jungle airstrips.

Conservative estimates suggest that at least 10,000 Japanese aircrew died in them. Seven men per bomber—that was the standard crew—multiplied by hundreds of missions where a wing ignited and there was no way out.

In the United States, B-17 and B-24 crewmen also died in large numbers—over Europe, over Ploesti, over Rabaul. But enough survived tours, enough came home bandaged and bloodied, to train the next wave. Experience accumulated. Tactics improved. The force got better.

In Japan, each burning Betty took with it an entire crew’s experience. They were not wounded and rotated to instructor billets. They were not retired to rear-area training posts. They were ash and memory.

By the last year of the war, green crews were climbing into unforgiving machines, guided by second-hand stories instead of first-hand instruction, flying into a sky dominated by radar-directed fighters and radar-guided flak.

The Betty had achieved its specification sheet perfectly.

It had terrorized Allied bases when no one could reach its own. It had killed capital ships in a way that changed naval warfare forever. It had given the Imperial Japanese Navy long, reaching fingers in the early days of victory.

It had done so by accepting a price in human lives that no American designer, no British board, would have tolerated.

American engineers had gone the other way. They had built bombers that were overbuilt, overweight, sometimes under-performing in range, but designed to keep their crews alive when hit. They had chosen to pay pounds and miles instead of men.

In the long run, that choice mattered more than any top speed or combat radius.

It meant that when the war demanded men who could lead complex missions, there were men who had flown twenty or thirty missions and survived to take those roles.

It meant that the American air forces could grow stronger through experience.

In contrast, Japan’s choice burned away its own expertise.

They built an extraordinary machine.

They built it by turning its crews into consumables.

Standing on the Clark Field tarmac, the sun finally sinking and the concrete radiating stored heat, Major Frank McCoy watched the captured Betty glow softly in the orange light and felt something he hadn’t expected.

Not triumph.

Not contempt.

Pity.

Not for the design. As an engineer, he could almost admire the ruthless clarity of the calculus that had produced it. No waste. No excess. A single-minded devotion to range and speed.

His pity was reserved for the men who had strapped themselves into that calculus, mission after mission, and flown until physics and .50-caliber rounds caught up with them.

He tipped his cap back on his head and walked away, leaving tail number 763-12 alone on the field.

Behind him, the Betty sat, its thin wings hiding nothing, its empty fuel tanks echoing faintly as the metal cooled.

In the fading light, it looked less like a weapon and more like what it really was.

A monument to a decision.

A flying death trap, built on purpose.

And, in the end, another wreck in a war that had shown that what nations chose to value when they drew their blueprints would echo long after the last shot was fired.

News

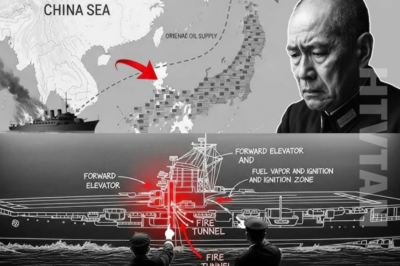

CH2. The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight

The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight The convoy moved like a wounded animal…

CH2. How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster Liverpool, England. January 1942. The wind off…

CH2. She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors

She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors The Mediterranean that night looked harmless….

CH2. Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming

Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming December 4th, 1944. Third Army Headquarters, Luxembourg. Rain whispered against…

CH2. They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass

They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass The Mustang dropped…

CH2. How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat

How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat The North Atlantic in May was…

End of content

No more pages to load