Captain Poured Coke on Her Head as a Joke — Not Knowing She Was the Admiral

Part 1

By 0700 the heat in the motor pool was already a living thing.

It rose in shimmers from the baked concrete and crawled under body armor and into boots, carrying the smell of diesel, burned coffee, and last night’s dust. The mountains around FOB Ghazni were just silhouettes in the distance, pale blue against a white-hot Afghan sky. The only shade came from the hulking shapes of MRAPs and up-armored Humvees lined up like metal bison in their pens.

First Lieutenant Brin Castillo stood in that thin strip of shade beside a maintenance bay, clipboard in hand, ballpoint pen ticking down the checklist in neat, tight strokes. Sweat slid between her shoulder blades. A strand of dark hair had pulled loose from her bun and glued itself to the back of her neck. She ignored it.

“Truck 27B, oil change logged?” she asked without looking up.

“Completed yesterday, ma’am,” Specialist Harper answered, wiping grease on his pant leg and flipping a laminated tag hanging from the door handle. “Filter changed, too. We’re just waiting on the new run-flat for the rear axle.”

Brin made a quick note, then snapped the cover of the clipboard closed.

“Get it mounted before 0900,” she said. “We’ve got a convoy stepping off at ten, and 27B is your lead. I’m not sending them out with a question mark on their wheels.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Harper said. He meant it. Nobody on base doubted her conviction when it came to trucks leaving the wire. If it wasn’t green, it didn’t go. If it went anyway, it wasn’t under her authority.

Brin shifted her weight and scanned the row of vehicles, the way she always did, scanning for sagging tires, streaks of fluid, loose straps. In her world, the enemy wasn’t just the Taliban. It was entropy.

Logistics wasn’t glamorous. It didn’t make highlight reels back home. There were no recruiting posters of a lieutenant standing in front of a pallet of hydraulic fluid with the caption, “This Is Where Wars Are Won.” But after six months on the ground with 10th Mountain Division, she’d learned the quiet math of this place.

A broken fan belt at the wrong time could kill as surely as a bullet.

She walked down the line, boots crunching on gravel, greeting soldiers by name. Brin didn’t raise her voice much. She didn’t have to. Her authority lived in the fact that her convoys rolled on time, that her trucks came back, that her people knew she wouldn’t ask anything of them she hadn’t done herself.

She’d earned that the hard way: slogging through ROTC at Texas A&M, graduating into a war that had already chewed through a generation, spending her first year as a butterbar learning how not to get in her NCOs’ way. She’d chosen quartermaster and logistics because someone had to make sure food and ammo and fuel got where they needed to go. She’d gone to Airborne school because she refused to tell soldiers to jump out of an aircraft if she hadn’t felt the static line snap herself.

Now she was twenty-nine, a first lieutenant, six months into her first deployment. The novelty had worn off. The stakes hadn’t.

“Ma’am,” Sergeant King called from the far end of the row. “We got a leak under 31F.”

She headed that way, pen already poised.

Behind her, at the edge of the motor pool, a small knot of soldiers in different unit patches filtered in, joking too loudly, their voices hitching above the hum of generators.

“Bravo Company,” King muttered. “Great.”

She didn’t have to ask what that meant. Everyone on FOB Ghazni knew Bravo Company’s reputation—hard-charging, aggressive, quick to volunteer for the nastier missions, led by an executive officer whose name drifted through conversations like a bad smell.

Captain Derek Holland.

Brin had seen him around. Tall, broad, the easy swagger of a man who’d never had to worry about whether anyone would take him seriously. He had an angular, handsome face that might’ve belonged on a recruiting poster if not for the permanent smirk carved into one corner of his mouth. Rumor said he’d come from a long line of officers, that his dad was a retired colonel with a golf buddy in every division.

Rumor also said he liked to “break in” junior officers the way some boys at her Texas high school had liked to break in green colts—loudly, publicly, and with a streak of cruelty they called “toughening up.”

It wasn’t that Brin scared easy. She’d led convoys through stretches of Highway 1 no one put on postcards. She’d flinched at the sound of rounds cracking overhead and kept her voice steady on the radio. But there was a particular kind of danger in men like Holland: the kind who thought their rank covered their character like body armor.

She had learned, years ago, that you couldn’t out-shout men like that. You could only be better than them. Cleaner. Sharper. Harder to knock off balance.

“Hey, Castillo,” King murmured, reading her shoulders. “Want me to run interference?”

“No,” she said. “We’ve got work. Let’s do it.”

King nodded and peeled away, barking at a private to fix a crooked mirror bracket.

Brin crouched beside 31F, squinting at the wet patch on the gravel. She rubbed it between her fingers. Clear, mostly. Not the dark, sticky sheen of oil.

“AC condensate,” she called. “Harper, sign off on—”

“You sure about that, Lieutenant?”

The voice came from above and behind her, dripping casual challenge. Brin straightened slowly and turned.

Captain Holland stood two feet away, hands on his hips, one boot propped on the bumper of a Humvee like he was posing for an action shot. His sunglasses were perched on his head despite the already brutal glare. His tan undershirt clung to his chest, sweat darkening it along the spine. A half-empty can of Coke sweated in his hand.

He was flanked by two lieutenants from his company and a handful of their soldiers, who had fanned out just enough to look like an audience without making it obvious.

“Good morning, sir,” Brin said evenly. “Can I help you with something?”

He let his gaze travel over her—name tape, rank, airborne wings, sleeves rolled tight in regulation two-inch cuffs. His lip curled, just a little.

“Just out here checking on my vehicles,” he said. “Didn’t realize we had logistics royalty managing the peasant carts.”

“My platoon’s responsible for the battalion’s rolling stock on this side of the FOB,” she said. “If you have a maintenance concern, I can pull your 5988Es and—”

He rolled his eyes. “Jesus, they really teach you kids to talk like the manual, don’t they?”

Behind him, one of his lieutenants smirked. Another shifted his weight, gaze flicking away.

Brin refused to bite. “Captain, I’m in the middle of a pre-combat inspection. If you’ll excuse me—”

He stepped sideways, blocking her path with his body.

“I’m actually curious,” he said. “How many times have you been outside the wire, Lieutenant?”

She blinked once. “Eleven convoys since we hit ground,” she said. “More if you count turnarounds into Ghazni City. All logged in SIGACTS if you want to look them up.”

“Paperwork,” he said dismissively. “Riding shotgun in an MRAP behind a wall of grunts is not the same thing as combat.”

She thought of the sudden bloom of dirt and fire on the horizon three months ago, the way the lead truck had rocked when the IED took a bite out of the road. She thought of the minutes spent pinned in place while their gunners poured suppressive fire into the tree line and she’d clenched her teeth so hard she’d tasted blood.

“I’m aware of the difference, sir,” she said. “And I don’t discuss my soldiers’ experiences like they’re not in the room.”

A few of her mechanics were watching from the shadows beneath a raised hood, expressions carefully blank. King’s jaw worked.

Holland took a lazy sip of his Coke.

“You logistics kids,” he said, turning his head just enough to project to his little audience, “always so sensitive. Out here pretending you’re warriors because you got dust on your boots.”

“If you have an issue with my performance,” Brin said, voice thinning with the effort to keep it level, “you’re welcome to bring it to my battalion commander. Until then, I suggest you let us do our jobs so your guys have trucks that start when you need them.”

For a heartbeat, something mean flashed in his eyes.

Then he smiled.

“Relax, LT,” he said. “I’m just messing with you. You look tense.”

He turned toward a battered cooler sitting on a crate nearby, popped it open, and fished out another can. Cold fog rolled off the ice.

Brin felt a prickle of unease slide up her spine.

“Sir,” she said. “We’re still in the middle of—”

He stood to his full height, shook the can once, twice, the thin metal hissing under his grip.

“You look like you could use a shower, sweetheart,” he drawled.

Before she could step back, before anyone could think to move, he upended the can over her head.

The world narrowed to the sound of hissing carbonation and the cold, sticky cascade of syrup and bubbles pouring down her hair, over her cheeks, under her collar. Coke soaked into her uniform, darkening the fabric, plastering it to her skin. It fizzed in her ears. It dripped off her eyelashes.

The motor pool went quiet.

Thirty soldiers froze in place, wrenches, clipboards, and weapons hanging in mid-air.

For a second, the only sound was the glug-glug of the last of the Coke leaving the can.

Holland held it there, letting it drain, as if he were anointing her.

“There we go,” he said, tossing the empty can into the trash with a clatter. “All cleaned up. Don’t take it personal, LT. Just a joke. You gotta learn to lighten up out here.”

A few of his soldiers chuckled weakly, the sound brittle. One looked away, jaw clenched. One of Brin’s privates took an involuntary step forward before King’s hand shot out and clamped on his forearm like a vise.

Brin didn’t move.

She felt the Coke trickle down her spine, pooling at the waistband of her pants. She felt her scalp prickle as the sugar started to dry, gluing hair to her skull.

Her fingers closed around the edge of the clipboard until her knuckles went bloodless.

Her father’s voice, from a different heat, a different range outside San Antonio, echoed in her head.

Discipline isn’t about what you do first, mija. It’s about what you do next. Anyone can pull a trigger when they’re angry. Not everyone can keep their finger straight when it counts.

She could hear Holland laughing. Could feel thirty pairs of eyes on her—some expectant, some horrified, some calculating.

If she shouted, if she shoved him, if she let the white-hot flare of humiliation explode into action, it would feel good.

For about five seconds.

Then it would live forever in someone else’s narrative: Emotional female lieutenant loses it over a joke. Can’t hack it in a combat zone.

So she didn’t move.

She blinked once, calmly, clearing Coke from her lashes. She looked down, saw a missed check mark on the maintenance log lying on the hood of the truck beside her, and picked up her pen.

“Harper,” she said, voice steady, “you didn’t annotate the torque check on the lug nuts for 27B. Fix it.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Harper said, voice a little strangled.

She keyed her radio with her free hand.

“Black Knight Six, this is Black Knight Two-Six,” she said. “Maintenance on convoy lead is behind schedule. Pushing departure by thirty minutes. Break. I’ll send updated timeline within ten.”

“Roger, Two-Six,” came her commander’s voice. “Make sure they’re green when they roll. Out.”

She clipped the radio back on her vest.

Then she turned and walked away.

Coke squelched in her boots with each step.

No one tried to stop her.

Holland watched her go, still grinning, and slapped one of his lieutenants on the shoulder.

“See?” he said. “Told you. They’re soft.”

What he didn’t know—what almost no one there knew—was that the name on her tape was not just a name.

It was a fuse.

And it had just started burning.

Part 2

Twenty minutes later, Brin sat behind her plywood desk in the logistics office, staring at a knot in the wall.

The air conditioner rattled weakly, struggling against the heat. The room smelled like dust, printer toner, and the sour-sweet tang of drying Coke.

Her uniform stuck to her skin. Syrup had crept down the collar, leaving a crust along her neck. Her hair, once scraped back smooth, now hung in damp, dark clumps. A droplet slid from her chin and landed on the incident report form in front of her, blooming the ink of a half-finished word.

She didn’t wipe it away.

She laced her fingers together on the desk, pressed until the ligaments ached, and forced herself to breathe in for four counts, out for four. Her heartbeat, which had been hammering against her ribs since the moment the Coke touched her scalp, started to slow.

On a shelf above the desk sat a framed photograph: her father and her, both in dress uniforms, taken on the day of her commissioning. In it, she was twenty-five, grinning, bars bright on her shoulders. He stood beside her, taller, shoulders still unconsciously squared the way thirty years in uniform had trained them, one silver star on his own chest glinting under the ceremony lights. Rear Admiral Victor Castillo, joint logistics director, Pentagon.

She’d asked him not to wear his medals that day. He’d done it anyway; not out of vanity, but because he believed the uniform meant something. Because for him it wasn’t about the metal. It was about the promise.

Respect is not given, he’d said in the car afterward, one hand on the steering wheel, the other gesturing in that way he had. It’s earned. Every day. And once you earn it, you never surrender it. Not for promotion. Not for comfort. Not because an idiot with more stripes than sense decides to see what he can get away with.

She had rolled her eyes, but she’d heard him.

He hadn’t told her to join the military. He hadn’t pushed her toward it. He’d just made it clear that if she ever did, she’d be held to a standard higher than the bare minimums.

Now, sitting there in a sticky uniform half an hour after a man with two more bars than her had used her as a prop in his little show, she thought about that conversation and felt something inside her snap into place.

She could already hear two competing voices in her head.

One said: Let it go. Don’t be “that lieutenant.” There’s a war on. People get shot out there. You got soaked with soda. Who cares?

The other said: Thirty soldiers watched your platoon leader get humiliated for sport. Some of them were yours. If you pretend it didn’t matter, you’re telling them it’s acceptable. You’re telling them their dignity is negotiable if it makes someone above them laugh.

Her father’s third voice cut through both.

You don’t fix rot by yelling at the mold, mija. You fix it by finding where the water’s coming from and turning the valve.

Chain of command. Documentation. No yelling. No theatrics. No ammo for anyone to call this a tantrum.

She pulled a fresh incident worksheet toward her and began to write.

Date. Time. Location. Parties involved.

Facts. Not adjectives.

She wrote: “At approximately 0715 hours, Captain Derek Holland, Bravo Company XO, approached myself and my soldiers in the motor pool during a scheduled pre-combat inspection…”

She did not write: He strutted in like he owned the place.

She wrote: “He made comments regarding my branch, experience, and suitability for operations outside the FOB…”

She did not write: He jabbed, and jabbed, and jabbed, and smiled every time he landed one.

She wrote: “Captain Holland then retrieved a can of Coca-Cola from a cooler, shook it, and poured it over my head and uniform in front of approximately thirty soldiers from both units. He stated, ‘You look like you could use a shower, sweetheart. It’s just a joke.’”

She did not write: My hands were shaking so hard I could feel the clipboard rattle.

She listed names. Specialist Harper. Sergeant King. Lieutenant West, Bravo Company. Private Collins. Anyone she could remember who’d been within line of sight.

She checked the box that said: “I believe this incident constitutes unprofessional conduct and may meet the threshold for harassment or hazing under AR 600-20.”

At the bottom, in the block for “Requested Action,” she hesitated.

Her pen hovered over the page.

She did not write: I want him gone.

She did not write: I want him to feel as small as he tried to make me feel.

She wrote: “Request formal review and appropriate corrective action per regulation. Documentation only. No preferential treatment requested.”

She signed her name.

First Lieutenant Brin M. Castillo, 10th Sustainment Brigade.

She made three copies. One for her files. One for her company commander. One for the battalion commander.

When she walked into Lieutenant Colonel Hayes’s office, her uniform was dry but still stained, dark Coke splotches ghosting her chest and shoulders. Hayes looked up from his laptop, eyes narrowing.

“Lieutenant,” he said. “You look like you lost a fight with a vending machine.”

“Sir,” she said. “Permission to speak freely?”

He blinked once, processing the request, then nodded. “Close the door.”

She handed him the report.

He read it without interrupting, lips pressed into a thinner and thinner line. Halfway through, he stopped, looked up at her, then back down at the page. When he finished, he set it on the desk and steepled his fingers.

“Anyone else been doing stupid shit on my motor pool that I should know about?” he asked, voice dangerously mild.

“Not to this extent, sir,” she said. “Sergeant King can confirm. So can half the maintenance platoon.”

He exhaled slowly through his nose.

“Sit down, Lieutenant,” he said.

She sat.

“This is… textbook hazing,” he said. “At best. At worst, it’s harassment. At absolute minimum, it’s unprofessional as hell. You understand that if I push this up the chain, it’s going to get messy.”

“Yes, sir,” she said. “I also understand that if I don’t, my soldiers will think I’m okay with being treated like that. And I’m not.”

He studied her for a long beat.

“Are you looking for… anything beyond this?” he asked carefully. “Any… attention drawn to the fact that—”

“No, sir,” she said quickly, knowing what he was about to say. “My last name is Castillo, not Castillo’s Daughter. I’m not asking you to use my father’s rank. I’m asking you to use the regulations.”

He nodded once, as if confirming something he’d suspected.

“Alright,” he said. “I’ll endorse it and send it up with a recommendation for a command-directed investigation. Holland’s battalion commander is Driscoll. He and I went to CGSC together.” He grimaced. “He’s… not my favorite person, but he’s not completely obtuse. He should know better than to sit on something like this.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

“And Lieutenant,” he added, “for what it’s worth? You handled yourself well. I’ve seen officers twice your rank lose their minds over less. You kept your bearing. You came to me. That’s textbook. Don’t let anyone tell you different.”

“Thank you, sir,” she said, and meant it.

As she stood to leave, he cleared his throat.

“And, uh… the other thing,” he said. “Regarding your… family.”

“Yes, sir?”

“You’re aware your father’s coming here?” he asked.

Her stomach dropped, even though she’d known.

“Yes, sir,” she said. “I was notified last week he’ll be doing an assessment for RC-East logistics.”

“He’ll be here in forty-eight hours,” Hayes said. “For what it’s worth, I got that memo before I got your report. The timing is… interesting.”

“Sir,” she said carefully, “I did not time this report around his visit. If anything, I’d prefer he not know about it at all.”

“Life rarely cares what we prefer,” he said wryly. “I’ll do my job. You do yours. Let the stars handle themselves.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

She walked back to her office lighter and heavier at the same time.

Outside, the motor pool had returned to its usual chaos. Engines revved. Wrenches clanged. Someone cursed as a socket slipped. Her soldiers glanced up as she passed, eyes flicking to the faded Coke stains on her blouse, then back to her face.

Her expression gave them nothing. No triumph. No defeat.

“Convoy pre-brief in twenty,” she called. “Nobody’s late. King, you’re up first with the route recon.”

“Yes, ma’am,” King said, and there was something new in his voice. A thread of something that sounded like… pride.

She grabbed a fresh blouse from her wall locker, changed quickly, wiped the last crusted sugar from her neck with a wet wipe, and got back to work.

Thirty miles away, in a staff office on Bagram, Rear Admiral Victor Castillo sat at a borrowed desk, reviewing a stack of reports from FOB Ghazni.

He wore desert cammies, name tape CASTILLO over his heart, a single silver star pinned to his collar. His hair had gone more salt than pepper in the last few years, but his eyes were still the same sharp dark as his daughter’s.

He flipped through spreadsheets on fuel consumption, PowerPoints full of bar graphs, after-action reviews on convoy delays.

Near the bottom of the stack, a new document caught his eye.

INCIDENT REPORT – UNPROFESSIONAL CONDUCT / POSSIBLE HAZING

Reporting Officer: 1LT Brin M. Castillo

His throat tightened. He forced himself to breathe, to not skip ahead, to read it like any other report.

As he read the description of the motor pool, the Coke, the words “sweetheart” and “shower” scrawled in his daughter’s neat handwriting, something cold settled in his chest.

He read Hayes’s endorsement. He read the routing slip from Driscoll’s inbox.

Your lieutenant needs thicker skin. I’ll counsel Holland informally. No need for an investigation.

Victor closed his eyes for a moment.

Rank without character is just noise, he’d told his kids. He’d meant it. He’d preached it. He’d bent his career around it, even when it hurt.

Now some captain thought humiliating his daughter in front of her soldiers was a joke.

He opened his eyes, for once feeling every year of his service in his bones, and reached for the phone.

“Get me the base commander at Ghazni,” he told his aide. “Now.”

On the other end of the line, a career began to unravel, thread by thread, and none of the men involved realized the hand tugging it belonged to the same quiet woman they’d watched walk across a motor pool and choose not to raise her voice.

Part 3

FOB Ghazni’s helicopter landing zone was a cloud of dust and rotor wash when Rear Admiral Victor Castillo stepped off the Chinook ramp.

He moved with the contained ease of someone who’d done this a thousand times—boots landing sure on the metal, hand automatically going up to secure his cover against the roar. The blast of hot wind caught his sleeves and rattled the papers in his aide’s hands.

The base commander, Colonel Sykes, waited just beyond the rotor arc, hand snapping up in a crisp salute.

“Admiral Castillo, sir,” Sykes shouted over the engines. “Welcome to Gazhni.”

Castillo returned the salute. “Good to be here, Colonel. Let’s get inside before I turn into jerky.”

They ducked into the TOC, where the air conditioner fought a losing battle but at least cut the noise. Maps covered the walls. A bank of screens showed live feeds from drones and ranges. Staff officers hovered over laptops, murmuring in low voices.

For the first day, everything unfolded according to script.

Briefings on supply routes. PowerPoint presentations on fuel theft mitigation. Walk-throughs of the ammo holding areas, the water treatment plant, the chow hall’s cold storage. Castillo asked pointed, technical questions that made captains shift uncomfortably in their seats and made staff sergeants perk up, relieved to be taken seriously.

He didn’t ask about his daughter.

He already knew more than he wanted to.

Brin, for her part, spent the day doing her job. She ran a convoy brief like she’d been trained to, her voice steady as she pointed to the map taped to the wall. She walked the line of soldiers readying their trucks, checking plates, straps, mirrors. She retasked a broken vic and reshuffled her order of march like a chess player adjusting to a missing knight.

She knew her father was on base. She knew he’d seen her report. Hayes had told her the truth.

What she didn’t know was when their worlds, carefully kept separate for years, would collide.

It happened on Day Two.

“Admiral,” Colonel Sykes said over lunch, “we’ve arranged for you to see the motor pool this afternoon. Lieutenant Colonel Hayes will walk you through their convoy prep. Our logistics here are… frankly, sir, they’re better than some of the other FOBs. He’s running a tight ship.”

“I noticed,” Castillo said. His tone was neutral. His eyes were not.

At 1400, the sun was still punishing. The motor pool shimmered, heat rising off the hoods of parked MRAPs.

Hayes waited at the entrance, spine a little straighter than usual. Beside him stood Brin, clipboard in hand, uniform pristine, nametape CASTILLO like a small gravity well on her chest.

When their eyes met, something in Victor’s chest twisted.

He hadn’t seen her in person in almost a year. Video calls didn’t do justice to the way her presence changed a room. She looked older. Not in a way anyone else would notice, maybe. But he saw the lines at the corners of her eyes, the slight tightness at her jaw. The set of her shoulders—carrying more than a ruck.

He made his face a mask.

“Lieutenant,” he said, voice formal, “I understand you’re responsible for this circus.”

“Yes, sir,” she said. Her salute was textbook. “First Lieutenant Castillo, 10th Sustainment Brigade, motor transport platoon leader. Welcome to Ghazni, sir.”

Her use of his rank, not his name, was as deliberate as his refusal to acknowledge anything personal.

“Walk me through your process,” he said.

She did.

She talked about daily inspection schedules, about the struggle to get filters on time, about cannibalizing non-mission capable vehicles for parts to keep the convoys rolling. She pointed out small innovations her NCOs had introduced—a color-coded tag system for quick visual status, a new way of organizing spare tires to shave minutes off swap times.

He asked her about the route security coordination with infantry. She answered. He asked about fuel losses on certain legs of Highway 1. She had a spreadsheet in her clipboard, printed and updated in ink.

As she spoke, the soldiers around them watched, curiosity barely hidden. They knew by now that the visiting one-star was her father. Rumors traveled fast. But this, this cold professionalism between them, was something else.

When the brief ended, Castillo nodded.

“Good work, Lieutenant,” he said. “Your readiness rates are above theater average. Keep it that way.”

“Yes, sir,” she said. “We will.”

He turned to Hayes.

“Colonel, I’ll need to borrow you for a few minutes,” he said. “Some follow-up questions.”

“Of course, sir,” Hayes said.

They stepped into a small office off the motor pool. The air inside was marginally cooler. Dust motes swam in the slanted light.

“Sir,” Hayes began, “I want to assure you—”

“Sit down, Lieutenant Colonel,” Castillo said. “I’ve read your endorsement. You don’t need to defend yourself.”

Hayes sat, wary.

Castillo took a folded report from his pocket and smoothed it on the desk.

“This is the incident involving Captain Holland,” he said. “Your lieutenant’s report. Your note. Driscoll’s response.”

“Yes, sir,” Hayes said carefully. “I forwarded it to his battalion with my recommendation.”

“And he decided a formal investigation wasn’t necessary,” Castillo said. “Because ‘junior officers need thicker skin.’”

Hayes’s jaw ticked. “Yes, sir.”

“Tell me honestly, Colonel,” Castillo said, “if this report had been written by Lieutenant Smith, 1-22 Infantry, and the victim had been a male officer, would you have accepted that answer?”

“No, sir,” Hayes said. “I’d have pushed harder. But Driscoll has… connections.”

“His father,” Castillo said. “Retired Colonel. Class of ’85. Golf buddy of a two-star who thinks his buddy’s kid walks on water.”

“Yes, sir,” Hayes said, surprised he didn’t have to explain.

“Connections don’t trump regulation,” Castillo said flatly. “Not on my watch.”

He straightened.

“I’m ordering a command-directed investigation into Captain Holland’s conduct,” he said. “Effective immediately. I’ve already spoken to Colonel Sykes. He’s on board. Holland will be temporarily relieved pending outcome. I want every witness statement, every scrap of paper on his previous ‘pranks’ pulled into the light.”

“Yes, sir,” Hayes said, relief cracking through his posture like a crack in ice. “Thank you.”

“This isn’t about my daughter,” Castillo added, and his gaze brooked no argument. “If she were anyone else’s lieutenant, I’d still be here having this conversation. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, sir,” Hayes said. And he did. He’d seen generals sweep things under the rug to protect their own. This felt… different. Cleaner. More dangerous.

“Good,” Castillo said. “Now get me Holland and Driscoll in a room. I’d like to hear their version of events. In their own words.”

The meeting was held that afternoon in a secure conference room near the TOC.

Captain Holland arrived in his best pressed uniform, hair trimmed, boots gleaming. He’d been told a general wanted to speak with him about an “incident” involving a junior officer. He assumed it would be a slap on the wrist at worst, a “watch your optics, Derek” chat delivered by someone who’d secretly sympathize.

Lieutenant Colonel Driscoll came in with him, face set in what he probably thought was an expression of concerned professionalism.

Admiral Castillo sat at the head of the table, hands folded. Colonel Sykes and Hayes flanked him.

“Captain Holland,” Castillo said, voice even. “Have a seat.”

“Yes, sir,” Holland said. He sat. He didn’t quite slouch, but there was a trace of arrogance in the way he leaned back, ankle resting casually on the opposite knee.

“Do you know why you’re here?” Castillo asked.

“Sir, I assume this is about the, uh, misunderstanding in the motor pool the other day,” Holland said, forcing a chuckle. “I’ve already spoken with my battalion commander. I apologized informally. Lieutenant Castillo and I—”

“Let’s start with your version of events,” Castillo said, cutting him off gently. “Tell me, in your own words, what happened.”

Holland swallowed, sensing for the first time that the room was not quite as friendly as he’d hoped.

“Sir, I went over to the motor pool to check on some of Bravo Company’s vehicles,” he said. “Lieutenant Castillo was there with her soldiers. I made a joke—ill-advised, in hindsight—about logistics officers spending too much time behind desks. She seemed… tense. I tried to lighten the mood.”

“And how did you do that?” Castillo asked.

“I, uh… I poured a Coke over her head,” Holland said. “It was… a stupid joke. I shouldn’t have done it. I told her as much afterward.”

“Did you ask her permission before you poured a sugary drink over her in front of her soldiers?” Castillo asked.

“No, sir,” Holland said.

“Did you consider how that might appear to the thirty or so soldiers present?” Castillo asked.

Holland shifted. “In the moment, no, sir. It was… spur-of-the-moment. I misjudged.”

“Did you, at any point, consider that your behavior might constitute hazing under AR 600-20?” Castillo asked.

Holland hesitated. “No, sir. I… guess I didn’t think of it that way.”

“Lucky for you, someone did,” Castillo said. He tapped the report on the table. “Lieutenant Castillo documented it. She followed the regulation you apparently didn’t bother to read.”

Driscoll cleared his throat. “Sir, if I may—”

“In a moment, Lieutenant Colonel,” Castillo said without looking at him. “We’ll get to your part in this.”

Driscoll closed his mouth.

Castillo turned back to Holland.

“Captain,” he said, “do you know who I am?”

“Yes, sir,” Holland said. “Rear Admiral Castillo, RC-East logistics assessment.” He pronounced “logistics” like it tasted bad.

“Do you know who Lieutenant Castillo is?” Castillo asked.

“A junior logistics officer, sir,” Holland said. “From 10th Sustainment.”

“Her full name,” Castillo said.

Holland frowned. “Uh… First Lieutenant Brin Castillo, sir.”

“And it never occurred to you,” Castillo said, “to ask yourself whether that name might be familiar for a reason?”

Holland blinked. “Sir?”

Castillo leaned forward, just enough that the overhead light caught the silver star on his collar.

“Captain Holland,” he said, voice dropping a shade colder, “First Lieutenant Brin Castillo is my daughter.”

Silence slammed into the room like a blast wave.

Holland’s face went sheet white. Driscoll’s jaw sagged a fraction before he jerked it shut.

“I… I… sir, I didn’t know—” Holland stammered.

“That’s the point,” Castillo said. “You didn’t know and you didn’t care. You saw a junior officer you thought you could use as a prop for your amusement. You didn’t bother to consider that she might have earned her rank. That she might have her own record of service. That she might have a family. That she might have someone whose job it is to review reports like this.”

He tapped the paper again.

“This is not about nepotism,” he went on. “If anything, consider yourself lucky. If she weren’t my daughter, the only reason I’d be paying this much attention to you is because your stupidity is jeopardizing the climate on this base.”

“Sir, I—”

“You poured a drink over a lieutenant’s head in front of her soldiers,” Castillo said. “You undermined her authority. You created a hostile work environment. You sent a message to every person watching that respect is optional if you think something is funny.”

He turned his gaze to Driscoll.

“And you,” he said, “received a formal report outlining this behavior, attached to previous informal complaints about this captain’s conduct, and decided to handle it with an ‘informal counseling’ chat because his daddy plays golf with someone important.”

“Sir, that’s not—” Driscoll began, color rising.

“Do not insult my intelligence,” Castillo said, and his voice, though still quiet, had the weight of artillery behind it. “I have been in this uniform longer than you’ve been alive. I have watched careers built and destroyed on the altar of who someone’s father had drinks with. I’m done with it. You are not protecting the Army by keeping people like this in leadership positions. You are hollowing it out from the inside.”

He sat back.

“Here is what is going to happen,” he said. “There will be a formal, documented, command-directed investigation into Captain Holland’s conduct—not just this incident, but prior documented behavior. Every witness will be interviewed. Every pattern will be examined. In the meantime, Captain Holland is relieved of his duties and reassigned to a non-command administrative role. Effective immediately.”

“Sir,” Holland blurted. “With respect, that’s… that’s my career.”

“No,” Castillo said. “Your pattern of arrogance and cruelty is your career. This is the appropriate consequence.”

He looked to Colonel Sykes.

“Colonel, you will ensure the investigating officer is not within Driscoll’s chain of drinking buddies,” he said. “I want clean eyes on this. No one with a dog in this fight.”

“Yes, sir,” Sykes said, jaw tight.

“As for you, Captain,” Castillo added, looking back at Holland, “you might want to start thinking about what kind of man you are when the bars come off. Because unless something miraculous comes out of this investigation—which I doubt—your days of using rank as a shield are limited.”

The meeting ended without theatrics.

No shouting. No slammed fists. Just orders, acknowledgments, and the hollow sound of a man realizing his trajectory had abruptly bent downward.

Three days later, Captain Derek Holland turned in his company files and moved his gear to a plywood office on the far side of the base, where he spent his days updating spreadsheets under the watchful eye of a major who had no interest in his opinions.

A month after that, a general officer memorandum of reprimand went into his permanent file. The words CONDUCT UNBECOMING AN OFFICER and PATTERN OF UNPROFESSIONAL BEHAVIOR nestled between references to rank and duty positions like rot in wood. Everyone in the room when it was signed knew what it meant.

He could finish his service, if he wanted. He could collect his paycheck. But promotion boards would see that letter before they saw anything else.

The fast track he’d imagined for himself—the battalion commands, the war college, the bird on his chest—faded like a mirage.

Back in the motor pool, convoys rolled out on time.

Brin’s soldiers watched the whole thing unfold not in a single cinematic moment, but in a series of quiet changes.

Holland didn’t show up at the motor pool anymore.

No one poured drinks on anyone’s head.

When a sergeant cracked an off-color joke at a private’s expense one afternoon, Corporal Darnell, who’d been there that morning in July, cut him off with a sharp, “Knock it off. That’s not how we do things here.”

Brin kept doing what she’d always done: she put her name on the line next to her convoys. She checked straps and manifests. She stood in the dust and shook hands when they came back through the gate, counting helmets by habit even when she knew the numbers.

Her soldiers respected her before. Now there was something else in their eyes when they looked at her.

It wasn’t reverence for her father. Most of them didn’t care what anyone’s parent did back in the States.

It was respect for the way she’d taken a hit, gone through the system, and kept her head when the man who’d tried to take it from her lost his.

She and her father didn’t talk about it while he was on base.

They passed each other in hallways, in briefings, in the chow line, nodding when protocol required it, ignoring each other when it didn’t. On his last night, he walked the perimeter with Sykes, nodding to the guards, eyes scanning the dark.

The morning he left, he found a folded note on his desk.

Sir,

Thank you for treating this as a professional issue, not a personal one. That’s the example you raised me to expect.

I’ll see you when we’re both back on the same continent.

– Brin

He folded it, slid it into his breast pocket, and spent the flight back to Bagram staring at the bulkhead, thinking about the strange balance of being proud of his daughter and furious on her behalf.

When he finally called her weeks later, after she’d rotated home, after she’d slept a full night without waking to the distant thump of mortar fire, he didn’t start with an apology for not doing more.

He started with the sentence he knew she needed to hear most.

“You handled yourself well, mija,” he said. “You were better than him. That’s all I ever asked.”

She let herself lean against the kitchen counter, eyes stinging, the Coke long washed out of her hair but the lesson of it still clinging to her bones.

“Thanks, Dad,” she said. “I had a good example.”

On the other end of the line, a one-star Admiral smiled into an empty office and felt the weird, looping satisfaction of knowing that somewhere out there, a captain was having to live without the shield he’d never deserved.

It wasn’t revenge.

It was balance.

Part 4

The Army didn’t keep Brin forever.

It tried.

She promoted to captain, took a company XO billet stateside, then a staff job at a corps logistics cell. She sat in windowless rooms and argued with majors over pallet allocations and priority of movement. She did well. Her OERs came back glowing with phrases like “poised for increased responsibility” and “demonstrates potential for battalion command.”

But something inside her had shifted after Ghazni.

Once you’ve seen how fast a quiet report can turn into a general’s signature and a captain’s GOMOR, you stop believing in the inevitability of any system.

She loved her soldiers. She liked the work. She hated the way the bureaucracy turned everything into a debate about PowerPoint fonts.

After eight years in, with a Combat Action Badge and a paragraph in a doctrine update she’d helped write, she hung up her active-duty uniform.

She didn’t walk away from logistics. She just changed battlefields.

Humanitarian disasters became her new front lines. Hurricanes, earthquakes, wildfires—places where roads washed out and supply chains snapped like twigs. She worked for NGOs and international agencies, applying the same ruthless efficiency she’d honed keeping convoys alive to getting water and insulin and tarps into broken cities.

She learned to navigate a different kind of arrogance: the kind that lived in boardrooms instead of TOCs. Men and women who’d never set foot in a motor pool but thought they knew exactly how to get food to a flooded village because they’d read a white paper once.

She smiled more now. She yelled more, too, when she needed to. The Coke incident hadn’t made her brittle. It had made her precise about when she spent her anger.

Her father promoted to two-star, then three, moving through billets like stepping stones: TRANSCOM deputy here, J4 there. Eventually, in a reshuffling that made headlines in the defense world and meant nothing to most Americans, he took command of a joint logistics force that spanned services and continents.

“Could’ve been you, you know,” he joked once over Christmas dinner, gesturing with his fork at his own Admiral’s stars. “If you’d stayed in.”

“I like being able to tell donors to shove their pet projects without worrying about a promotion board,” she said dryly. “Besides, Navy whites do nothing for my complexion.”

He laughed.

Life moved.

She got married, briefly, to a paramedic she’d met on a response mission. It didn’t last. Two people used to running toward other people’s emergencies don’t always have the skills to sit still with each other’s.

She didn’t have kids. Not because of the war. Not because of the Coke. Just because life had filled itself with other responsibilities, and one day she looked up and realized forty was closer than thirty and she was okay with being the aunt who showed up with loud toys and left before bedtime.

And then, because the universe has a sense of humor, the Navy came calling.

Technically, it was the Navy Reserve. They were building out a new concept—something between a combatant command and a logistics think tank—focused on contested resupply in a world where enemies had satellites and cyber tools and the ability to choke sea lanes.

They needed people who could think joint. People who had seen both sides: the battalion logistics officer on the ground and the staff officer moving pins on a global map.

“Have you ever considered coming back in uniform?” the recruiter asked over a video call, the Navy emblem glinting on his wall behind him. “Reservist. Five weeks a year away from your day job. We’re standing up a new directorate. Promotions track is… promising.”

She laughed. “Promising promotions,” she said. “You really know how to talk dirty to an old Army captain.”

“Old?” he scoffed. “You’re, what, late thirties? We’ve got Commanders older than the ships they’re on.”

She hesitated.

She missed certain things. The clarity of rank structure. The way a problem set came with a clear left and right limit. The knowledge that if she needed three trucks on a flightline at 0300, she could make that happen with a phone call and a properly formatted request.

She did not miss the smell of barracks on a Sunday morning. She did not miss safety briefs delivered by majors who thought reminding grown adults not to drink and drive was a substitute for leadership.

But joint logistics—sea, land, air, cyber—intrigued her.

“Would I have to wear those little white hats?” she asked.

“Only if you’re on a boat,” he said. “We’re more likely to stick you behind a screen than a wheel.”

“Sold,” she said. “Send me the packet.”

Hundreds of forms, medical exams, and background checks later, she stood in a small ceremony room, right hand raised, swearing an oath she’d technically never stopped believing in.

“Do you, Brin Marisol Castillo, solemnly swear—”

“I do,” she said.

They pinned gold oak leaves on her collar that morning: Lieutenant Commander. O-4. Equivalent to a Major. The insignia felt foreign and familiar all at once.

“Welcome aboard, ma’am,” her new boss said. “We’ve got some captains who think containers move themselves. You’re gonna ruin their whole worldview.”

She grinned. “Can’t wait.”

Reservist or not, the Navy moved fast when it liked someone.

She threw herself into the work. Wargames. Tabletop exercises. Red-teaming scenarios where Chinese missiles bracketed Guam and hypothetical hackers shut down GPS across a theater. She wrote white papers on fuel bladders and floating depots. She offended a few ship drivers by suggesting their beloved carriers were giant, vulnerable targets that needed smarter support than just more escorts.

She also made friends. Good ones. A Lieutenant Commander from the Coast Guard who knew more about ice than most people knew about their own extended family. A Marine major who’d spent his whole career figuring out how to get ammo to guys on island chains you couldn’t find on a globe.

She promoted, slowly and then quickly.

Commander. Then Captain.

The irony never left her: the woman who’d been humiliated by an Army captain in a dusty motor pool became a Navy Captain with command of a staff that could re-route entire supply lines with a signature.

She was in her mid-fifties, hair threaded with silver now, when the board convened for flag officers.

She didn’t expect to make the list.

Her father, retired by then, called her at some ungodly hour, voice gleeful.

“Admiral,” he said.

She sat up in bed. “What?”

“You heard me,” he said. “Rear Admiral (Lower Half), United States Navy. They released the list thirty minutes ago. Your name’s on it. Mija… you did it.”

She laughed, disbelieving and giddy and a little nauseous.

“You realize this means you can’t make fun of me for being a flag ever again,” he added.

“Oh, I can make fun of you more,” she said. “I outrank you now. Technically.”

He snorted. “Technically, yes. In reality… you’ve outranked me for a while.”

The ceremony was small, as these things went. Navy whites. Family in the front row. Her father, in a dark suit now, eyes suspiciously shiny as he and a mentor from TRANSCOM pinned the single silver star on her shoulder.

“I knew you’d end up here,” her father whispered as he stepped back, voice hitching. “You were always the one fixing my systems when I wasn’t looking.”

She gave her remarks, short and to the point.

“This star doesn’t mean I’m smarter or better than I was last week,” she said. “It just means I’m responsible for more people and more failure points. My job is to make sure the systems you rely on don’t break when you need them most. And if someone pours Coke on your head for doing your job, my job is to make damn sure the system doesn’t let them keep their command.”

Somewhere in the back, a junior officer who had never heard of Holland but had heard the story of a long-ago motor pool humiliation sat a little straighter.

The story had grown in the telling over the years.

Some versions got the details wrong. They moved the location from Ghazni to Kandahar. They turned the Coke into a protein shake. They swapped out “sweetheart” for something uglier.

But the core remained.

A captain with a bad habit.

A lieutenant who refused to play along.

A general—later an Admiral—who used his rank the way it was meant to be used: not as a shield for ego, but as a lever for accountability.

And now, in a twist that would’ve made some YouTube thumbnail artist cackle, the title was literally true.

The captain who’d poured Coke on her head all those years ago had not known he was humiliating a future Admiral.

He’d just thought she was another disposable junior officer.

He’d been wrong.

Part 5

The exercise was called Pacific Shield, which was the kind of name that sounded impressive on briefings and slightly ridiculous when you’d been awake for thirty-six hours watching little blue icons crawl across a digital ocean.

Rear Admiral Brin Castillo stood at the back of the joint operations center, arms folded, eyes on the main display. Carrier groups, resupply ships, submarines, island bases—her domain. She could feel the fatigue behind her eyes, but the old Ghazni part of her brain was still ticking, still rebalancing convoys and fuel loads and maintenance schedules in the background.

“Ma’am,” a young Navy Lieutenant said, hurrying up with a tablet. “We’ve got a concern from Task Force 37. Their logistics element is complaining that the Marines keep changing their resupply requests without notice.”

“Of course they are,” she murmured. “Semper Gumby.”

The lieutenant blinked. “Ma’am?”

“Always flexible,” she translated. “What’s the actual issue?”

He hesitated. “Well… honestly, ma’am, some of it seems… cultural. The TF-37 captain in charge of the carrier’s supply department keeps shutting down the logisticians when they try to explain the knock-on effects. Won’t listen. Told one of the joint staffers to ‘go back to counting boxes’ in front of the whole watch floor.”

Something old and sharp pricked under her ribs.

She held out her hand. “Let me see the complaint.”

He passed her the tablet. She skimmed the report. The captain’s name jumped out at her.

CAPT HOLLAND, DEREK J., USN

For a heartbeat, the room tilted.

She had known, in an abstract way, that there were more Hollands in the world. Arrogance wasn’t a single man. It was a fungus that grew wherever conditions allowed.

But to see the same name, attached to a different body, itching to repeat the same pattern on a different stage?

It felt like the universe handing her a test.

“Get me a secure line to TF-37’s flag bridge,” she said. “Now.”

Minutes later, she stood in a smaller conference room, a wall screen showing the slightly laggy face of a Rear Admiral halfway across the Pacific. Beside him, just in frame, stood a man in khakis with Captain’s bars and the kind of confident slouch she recognized.

“Castillo,” the other Admiral said. “Didn’t expect a call from the logistics czar in the middle of this.”

“You’ve got a personnel issue,” she said without preamble. “Your supply captain is undermining my joint logisticians. I have a formal complaint on my desk that smells like something I’ve seen before.”

She turned her gaze to the man beside him.

“Captain Holland,” she said. “Want to explain why you thought it was appropriate to tell a Lieutenant Commander with two Iraq tours that his job is ‘counting boxes’?”

He blinked, clearly surprised to be addressed directly by a one-star halfway around the world.

“Admiral, with respect,” he said, smile practiced, “we’re in the middle of a high-tempo evolution. People are tense. It was a… poorly worded attempt to keep people focused.”

“Ah,” she said. “A joke. To lighten the mood.”

He shifted, just a hair.

“Ma’am, I didn’t mean anything by it,” he said. “We all bust each other’s chops out here. That LT needs thicker skin.”

Somewhere deep in her bones, she felt the cold, sticky trickle of Coke again.

“You’re right about one thing,” she said. “I have heard that exact line before.”

He frowned. “Ma’am?”

She stepped forward, letting the overhead light catch the star on her collar.

“Captain,” she said, “do you know who I am?”

“Rear Admiral Castillo,” he said. “J-4 Pacific. Ma’am.”

“Do you know what my first job in uniform was?” she asked.

He opened his mouth. Closed it. “No, ma’am.”

“Army logistics,” she said. “FOB Ghazni. 2014. Motor pool. Convoy lead. One morning, an Army captain walked into my motor pool, poured a can of Coke over my head in front of my soldiers, and told me I needed to ‘lighten up.’”

His eyes widened.

“Ma’am, I—”

“He thought it was funny,” she said. “He thought rank gave him permission. He thought it was just another Tuesday.”

She held his gaze.

“He also thought he’d never see consequences,” she went on. “Because he assumed the system would protect him. Because he assumed the junior officer he was humiliating was alone.”

She let the silence stretch.

“He was wrong,” she finished. “So are you.”

On the other side of the connection, the other Admiral shifted, clearly uncomfortable.

“Captain,” he said quietly, “I was not aware of… the pattern described in this complaint.”

“That’s because it’s new,” Brin said. “Which is why we’re having this conversation now instead of in an IG hearing six months from now. I’m not interested in ruining your career over a single stupid sentence, Captain. I am very interested in making sure you understand that if I see a pattern of you using your position to belittle the people whose knowledge you depend on, I will not hesitate to do exactly that.”

He swallowed. “Yes, ma’am.”

“You will apologize to Lieutenant Commander Hsu in person,” she said. “You will sit down with my joint logisticians and you will listen to their constraints. You will not dismiss their concerns as ‘counting boxes.’ If you have questions, you will ask them like a professional. Not like a frat boy with a shiny anchor on his chest.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, cheeks flushing.

“And Admiral Chen,” she said, addressing the other flag, “you will make it clear to your wardroom that joint support officers are not punchlines. They’re the reason your planes don’t fall out of the sky for lack of fuel.”

He winced. “Understood, Castillo. Consider it handled.”

She nodded once.

“And Captain?” she added.

“Ma’am?”

“Next time you feel tempted to make a joke at someone else’s expense in a public space,” she said, “ask yourself one question: if they turned out to be an Admiral, would you still think it was funny?”

He opened his mouth, then seemed to think better of whatever he’d been about to say.

“No, ma’am,” he said. “I would not.”

“Good,” she said. “Then don’t.”

She ended the call.

For a moment, she stood there, hand still on the table, feeling her pulse in her fingertips.

She thought of the original Holland, somewhere back in the States now. She’d heard, through the grapevine, that he’d left the Army after his O-4 board passed him over twice. Last she’d heard, he was managing a logistics warehouse for a big-box store. She didn’t wish him ill. She didn’t wish him much of anything.

He’d become a cautionary tale in some corners of the service. Not because he’d been especially monstrous, but because he’d been so boringly, predictably arrogant—and had finally, for once, met a system that refused to shrug and move on.

She picked up her coffee, now lukewarm, and walked back into the main operations center.

On the big screen, icons still crawled. Logistics lines still pulsed. Lives still hung on things most people never thought about.

A young ensign at a side console glanced up as she passed.

“Ma’am,” he said, hesitating, “is it true? What you said. About… the Coke.”

She raised an eyebrow. “You doubting your Admiral’s word, Ensign?”

He flushed. “No, ma’am. I just— That’s… messed up.”

“It was,” she said.

“How’d you not… you know. Deck him?” he asked, eyes wide.

She thought of thirty soldiers in a hot motor pool, watching. Of her father’s voice in her head. Of the taste of Coke and dust and the metallic tang of swallowed anger.

“Because I knew something he didn’t,” she said.

“What’s that, ma’am?” the ensign asked.

She smiled, small and sharp.

“That rank without character is just noise,” she said. “And that sooner or later, someone with both is going to hear it.”

He nodded, slowly, like he was filing it away under Things They Don’t Put In The Manual.

She walked to the back of the room, where a giant digital map displayed fuel levels at sea.

“Ma’am,” the joint duty Marine major said, pointing at a cluster of icons, “we’ve got a tanker that’s not going to make it to station if we don’t adjust the flow through Andersen.”

She studied the display.

“Then we adjust,” she said. “No one runs dry on my watch.”

As she started issuing orders—rerouting ships, shifting air missions, waking up someone in Guam with a phone call they wouldn’t like but would respect—she felt the old, familiar satisfaction of systems clicking into place.

She was, in that moment, exactly who she’d always wanted to be: the person in the background making sure things worked, whose power lived not in how loudly she could humiliate someone, but in how quietly she could move mountains.

Somewhere, a young lieutenant stood in a motor pool on some other base, dealing with some other petty cruelty. Maybe they’d seen her story on a screen. Maybe they’d never hear it phrased the way YouTube liked to phrase things.

Captain Poured Coke on Her Head as a Joke — Not Knowing She Was the Admiral.

But they’d feel its echo in the way their commander responded when they filed their report. In the way some chain of command, somewhere, decided not to shrug. In the way some senior officer, somewhere, decided that the quiet logistics kid was worth listening to.

Brin didn’t need them to know her name.

She just needed them to know this:

You do not have to surrender your dignity to stay in the fight. You do not have to become the loudest person in the room to be the most powerful.

Sometimes, the most dangerous thing you can be is calm while your enemies mistake you for harmless.

Sometimes, the can they pour on your head is just the beginning of the story.

The ending is up to you.

She adjusted her cover on the way out of the ops center, star on her shoulder catching the light, and stepped into the gray morning, already thinking about the next problem that needed solving.

True power, she knew, didn’t need to make a mess to prove it existed.

It just needed to show up, do the work, and let the results speak for themselves.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Family Ignored My Graduation — Then My $5 Million Penthouse Made Them Pay Attention…

My family skipped my graduation, but the moment my $5M penthouse made real-estate headlines, everything changed. A single text from…

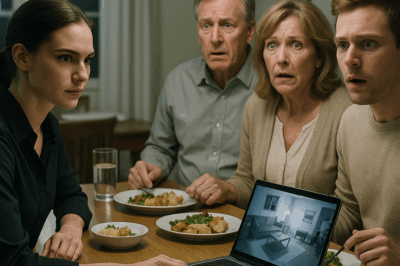

I Caught My Parents On Security Camera Planning To Give My Brother My Apartment – So I Set A Trap & Exposed Everything At Dinner…

I Caught My Parents On Security Camera Planning To Give My Brother My Apartment – So I Set A Trap…

My husband yelled “How dare you say no to my mother, you stupid!” At the family party, he even sma…

My husband yelled, “How dare you say no to my mother, you stupid!” At the family party, he even smashed…

“Someone Like You Doesn’t Deserve to Sit Here.” My Dad Pulled the Chair Away.Then a General Stood up

“Someone Like You Doesn’t Deserve to Sit Here.” My Dad Pulled the Chair Away. Then a General Stood Up …

My CIA Husband Called Out of Nowhere — “Take Our Son and Leave. Now!”

My CIA Husband Called Out of Nowhere — “Take Our Son and Leave. Now!” Part 1 The sound of…

I Warned the HOA for Months About a Landslide — They Ignored Me and Nearly Lost Their Lives

I Warned the HOA for Months About a Landslide — They Ignored Me and Nearly Lost Their Lives Part…

End of content

No more pages to load