Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call.

Part 1

“How long have you been with us, Melody—29 years, is it?”

David Langston leaned back in his leather chair, one ankle resting on a knee, his voice eerily casual, as if he were asking about the weather rather than my life.

“Twenty-nine years and three hundred sixty-two days,” I replied. I kept my tone steady even as my stomach knotted. A manila folder sat on the corner of his desk, precisely squared with the wood grain. In almost three decades at GrantWell Manufacturing—GRW to the analysts and the papers—I had never been summoned to a director’s office on a Friday afternoon. Something was wrong. Something had been wrong for years.

I’m Melody Reynolds, sixty-one years old, and until five minutes before I sat down in that chair I was the senior compliance officer at one of St. Paul’s largest manufacturers. For nearly three decades I was the person who read the parts of the documents everyone else skimmed, the woman who kept her own pen in her pocket because the company pens had a way of going missing, the voice in a meeting who said, “We can’t do it like that,” and then stayed late to find a way we could.

My pension was set to fully vest on Monday. Three days away. The milestone I carried through the funerals, the late nights, the missed recitals, the smaller disappointments that make up a career and a life. I had kept the number in my head like a prayer.

David nudged the folder toward me. “Due to budget constraints, we’re letting you go.”

He didn’t meet my eyes. He tapped the folder with a manicured finger.

“Effective immediately.”

The room tilted a degree. Budget constraints? GRW had announced record profits last quarter. I could quote the earnings call: improved operating margin, favorable commodity pricing, efficiencies in the supply chain. I had written the compliance footnotes.

“This is your severance package,” he went on, the performance smooth. “Sign by tomorrow or get nothing. HR will escort you to clean out your desk.”

I should have felt anger. Shock. The urge to defend myself. Instead, a strange calm slid into place. This wasn’t random; it was a pattern. Precision-timed to fall three days before my pension vested. I had taught analysts how to recognize schemes by their symmetry. This one was textbook.

“Thank you for the opportunity,” I said, rising. I lifted the folder without opening it.

He blinked. He had expected tears, protests, bargaining. But my career had been an exercise in noticing, and I had noticed enough.

Janet from HR hovered as I packed a cardboard box: the photo of my late husband Thomas laughing in the rain, the potted succulent my daughter gave me when she left for college fifteen years ago, the 25-year service plaque with my name engraved a hairline off-center. I didn’t take much. Most of what mattered couldn’t be carried.

“I’m so sorry, Melody,” Janet whispered, glancing at the security guard stationed a respectful distance away. “This isn’t—”

“It is what it is,” I said. Inside, another sentence finished itself: No, it isn’t.

For four years I had documented irregularities that accelerated after David arrived. I sent memos, footnoted and indexed. I flagged back-dated quality control certifications, “round-tripped” shipments that made revenues look plumper than reality, loan applications with numbers smoothed into lies. Documentation vanished into inboxes as if swallowed by a lake. I followed procedure. Procedure did not follow me back.

The security guard held the lobby door open. “Have a good weekend, Mrs. Reynolds,” he said, and the way he looked at the sidewalk told me he hated being the end of the hall.

“I believe I will,” I said, and stepped into the April rain.

I drove through a city that had held the chapters of my life—the cathedral where Thomas and I said vows, the school where our daughter walked across a stage in a blue robe, the hospital where the cardiologist explained statistics to me as if numbers could soothe. The wipers beat a patient rhythm. I turned onto my street and parked, hands quiet on the wheel. I sat for one breath and let the truth fully arrive: twenty-nine years of showing up ended with a folder on a desk and a date circled on a calendar like a bull’s-eye.

Tea. When there is nothing to be done, there is always water to boil. I set the kettle on, laid the severance packet on my kitchen table, and finally opened it.

Three months’ salary in exchange for a signature that would waive every right I had. No pension. No COBRA. No acknowledgement of the years I could count by paperweights and coffee mugs. The deadline, 5:00 p.m. Saturday. They were counting on fear and the weekend to hurry me.

I slid the packet aside and went to the small office where I keep records the way other people keep keepsakes. Behind a row of photo albums—Thomas with gravy on his tie; Elizabeth in a Halloween costume that never fit quite right—sat a fireproof lockbox. My insurance policy. For four years I had brought home copies of the troubling documents. Not because I planned to use them, but because my professional instincts wouldn’t let me trust a system that kept misplacing the truth.

I unlocked the box and began to read as if I didn’t know what I would find: loan applications that massaged reality until it purred; quarterly reports whose numbers had learned to dance; an email chain instructing a junior analyst to “adjust the ship date to align with targets” three weeks after the trucks rolled. Over a thousand pages. Names. Timestamps. IP addresses. The map of a pattern.

I picked up my phone. Scrolled to a contact I hadn’t used in years. Gregory Santos. He had been GRW’s CFO before he left to take a job at the Securities and Exchange Commission. He was the kind of man who returned a pen to the exact spot you set it down and read every page you gave him, even the boring ones. He had been one of the few who thanked me for being tedious.

I hovered over his name for one breath. Then I tapped.

We spoke for two hours, the kettle cooling on the stove, the tea forgotten. I explained what I had seen. He asked cross-examination questions with the gentleness of a doctor setting a bone. When I finished, he exhaled.

“This isn’t just wrongful termination, Melody,” he said. “Based on what you’re describing, GRW could be facing securities violations that make budgets look like gossip. The pension timing… that’s ugly, but it’s the tip of the iceberg.”

He explained the SEC’s whistleblower protocols. The protections. The admonitions. “Don’t sign a thing,” he said. “Secure those documents somewhere safe. Can you come downtown Monday morning?”

“I can,” I said, and felt a part of me stand up straighter.

Saturday, I woke like I had a job. I made copies. Three full sets, each page stamped and indexed, each binder clipped and labeled: SEC / Personal / Leverage. Organization has always been my way of choosing courage. My phone buzzed with calls I didn’t answer. Janet, nervous and apologetic. The company’s general counsel, brusque and “imperative.” David himself, smooth turned strained. We need that paperwork signed today. I can come by if that helps.

At 4:30, my doorbell rang. I watched David through the peephole as he shifted his weight in a neighborhood he wouldn’t visit on purpose. He slid an envelope into my mailbox and called to my door, “This is ridiculous, Melody. Sign the papers and we can all move on.”

I waited until he reached his car. I retrieved the envelope. The same agreement, the same trap, the same handwriting on a sticky note: Final opportunity. 9:00 a.m. Monday.

That evening my daughter called for our weekly check-in. She knows my voice the way I know her laugh; she heard the difference.

“Mom? What’s going on?”

I looked at the photo of Thomas on my desk, the line of his smile. “I was terminated yesterday,” I said.

“What? But—your pension—Monday— They can’t do that.”

“They did,” I said. “But don’t worry. I’m handling it.”

“I can fly in tomorrow.”

“No. Stay in Denver. Kiss my grandbabies. I’ve got this.” I meant it. I felt it in my bones the way you feel a storm before the radar shows it.

Sunday night, I slept. Not well. Not deeply. But the kind of sleep that insists on being ready.

Monday, I put on the navy suit I wear for important conversations, the one that makes me look like someone who doesn’t need to explain herself twice. The federal building’s lobby smelled like disinfectant and quiet. Gregory met me at security; the lines at the corners of his eyes looked deeper, but the mind behind them was the same.

“I wish we were meeting under better circumstances,” he said.

“Better circumstances are rarely this clear,” I replied.

He led me to a conference room of glass and carpet where two people waited. Angela Brennan, senior enforcement attorney, shook my hand with the kind of pressure that says I see you. James Weston, forensic accountant, nodded like a man who doesn’t waste agrees. We sat. Angela laid out the stakes.

“Mrs. Reynolds,” she said, “once you share this with us, the process begins. There’s no un-doing it.”

“I understand,” I said.

For three hours I walked them through the spine of the case. First, the shipments that never matched the invoices until after quarter end; then the quality control certifications that liked to travel backward through time; then the revenue “seasonality” that miraculously aligned with analyst expectations. James paged through documents and made small, unhappy sounds in the back of his throat.

“These aren’t rounding errors,” he said at last. “This is eighteen percent overstatement across at least eight quarters. That’s… not a misunderstanding.”

“And you reported these internally,” Angela said.

“Repeatedly,” I said, sliding across printed copies of memos with dates and the subject lines no one wanted to see: Variance Explanation Request / Recognition Timing; QC Certification Lag; Third-Party Distributor Exposure. “When David arrived, my reports started… disappearing. My meetings were rescheduled into oblivion. I was told to ‘support the narrative of success.’ I was told I was misinterpreting the data. Then I found directive emails to adjust downstream reports. Then I was told to focus on more ‘pressing’ matters.”

“And three days before your pension vests…” Gregory said.

“Here we are,” I finished.

We covered whistleblower protections. Potential retaliation. How the SEC would contact GRW’s counsel. What would happen next and how slowly or quickly “next” might arrive.

“Don’t sign the severance,” Angela said at the end, though she knew I wouldn’t. “And put the originals somewhere no one can confuse them with copies.”

I hadn’t even pulled onto I-94 when my phone rang. Janet.

“The board just called an emergency meeting,” she whispered as if the walls of her office could tell. “David’s locked in his office. People are saying SEC investigators called our general counsel. Melody… did you…?”

“I did what I should have done a long time ago,” I said gently. “Janet, what are they saying about my termination?”

“It’s on hold—your pension paperwork—everything—until the executive committee reviews it.” She sounded relieved and terrified in equal measure.

An hour later, the chairman of the board called. William Hargrove has a voice made for lecterns and microphones. It sounded smaller over my phone.

“Ms. Reynolds,” he said, “we seem to have a situation that requires your input. Would you be willing to come to the office tomorrow morning to discuss matters?”

“I’m afraid that won’t be possible,” I said. “Any discussion should include my attorney and, depending on your counsel’s preference, representatives from the SEC. I’m sure you understand.”

Silence. Then a throat cleared. “We… will arrange something formal.”

I set the phone down and stared out my kitchen window at the neighbor’s maple, just beginning to green. I had never wanted to be a whistleblower. I wanted to do my job, file my reports, retire on a Monday with a cake in the break room and a lunch that felt sincere. But the company had made a choice. Now I would make mine.

By Wednesday, the storm had names. Local business publications ran headlines. A market blog posted a chart with a red line that dove like a gull. Analysts who had praised David’s “efficiencies” last week used the word governance with a frown. My mailbox filled: a certified letter from GrantWell’s legal team rescinding my termination and placing me on paid administrative leave pending “internal review,” a gesture as transparent as it was late.

At 10:00 a.m., my attorney—Barbara Reynolds, no relation, though the coincidence amused us both—walked with me into GRW’s boardroom. The security guard who had held the door for me on Friday stood and nodded, as if we shared a secret.

William sat with outside counsel, his tie slightly askew. Three other board members looked like they’d aged a year per day since Monday. David was not there.

“Ms. Reynolds,” William began, “we’ve initiated a comprehensive internal investigation into the concerns you’ve raised.”

Barbara spoke before I could. “Let’s be clear, Mr. Hargrove. My client didn’t suddenly have concerns after her termination. She raised them repeatedly for four years—as her job required. Your decision to ignore those reports and terminate her three days before her pension vested speaks for itself.”

He swallowed. “Yes, well, that’s part of what we’re… investigating. Your termination has been rescinded. We consider you an employee in good standing with all benefits intact.”

“Including my pension,” I said.

“Of course,” he replied quickly. “In fact, we’re prepared to offer you a consulting role to begin immediately upon your retirement. We value your expertise.”

“My client isn’t making decisions today,” Barbara said. “And any discussion about future arrangements belongs after a full accounting of how her prior reports were suppressed.”

They tried to build a narrative where they, too, were victims. Investors had pressured. Information had been misrepresented. They had been misled by a few bad actors. I listened. I observed. I noted which board members couldn’t stop looking at the table and which kept glancing at the door.

When we rose to leave, William tried one last piece on the chessboard. “Ms. Reynolds, we hope you’ll speak to the SEC about the corrective actions we’ve already begun.”

I looked at him for the first time in a way that required him to see me.

“For twenty-nine years I did nothing but tell you the facts,” I said, my voice even. “I filed forty-seven major compliance reports. I sent sixteen memos regarding the exact issues now under investigation. I requested nine meetings with executive leadership; you granted two; nothing changed. I will cooperate fully with the SEC and with your internal investigation. I will speak to the facts. Whether those facts help you or harm you depends on what you do next—not what you say to me today.”

In the parking lot, Barbara exhaled. “Perfectly stated.”

“What happens now?” I asked.

“Now they scramble,” she said. “And they’re not afraid of you, Melody. They’re afraid of paper.”

“Close,” I said. “They’re afraid of the truth paper makes unavoidable.”

By Friday—exactly one week after the folder—the story had a rhythm. The SEC issued formal requests. The board suspended David “pending investigation.” The stock dropped another sugar-sick point. Business journals called me whistleblower, a word that fit like a borrowed coat. I did not read the comments. I did not count the clicks. I counted binders.

Gregory called. “It’s worse than we thought,” he said, voice low. “The manipulation goes back five years. He accelerated it. He didn’t start it. At least three board members signed off on transactions that only make sense if the numbers were already crooked.”

I’d suspected. Suspicion is not the same as proof. Proof tastes like metal and relief at the same time.

That afternoon Elizabeth called. I could hear a blender in the background and a toddler insisting the dog belonged on the couch.

“Mom, have you seen the news?” she asked, fierce. “He’s telling people you had performance issues. That you’re bitter because you didn’t get promoted. He’s saying you fabricated.”

Attack the witness when the evidence won’t bend. It was so predictable that the sting felt insulting.

“I’ve kept my performance reviews,” I said. “So has HR. So will the SEC. The dog can stay on the couch.”

Barbara called. “Don’t respond,” she said. “Let the official channels handle it.”

“I won’t respond,” I said. “But I will do something else.”

Saturday morning, I went to the bank. Tracy, the branch manager, has watched me deposit paychecks with the same neat signature for two decades. She took me to a private room and pulled a safe-deposit box no one had asked about in three years. Inside, a sealed envelope labeled in my handwriting: Acquisition Correspondence. During an archive project years ago I had uncovered an email thread between David’s predecessor and two board members, discussing how to “manage optics” during a critical acquisition—language that smelled like smoke. I had made a copy and put it somewhere that wouldn’t show up in a discovery request with my name on it for as long as possible. I hadn’t included it in my first SEC meeting because I thought I wouldn’t need it.

I needed it.

I called Gregory. “I have something that shifts the story from a bad man to a bad culture,” I said. “You’ll want it.”

Monday morning—ten days after the manila folder—an emergency board meeting convened without me. I sat with coffee I didn’t drink and watched a neighbor hose down his driveway as if it mattered. Gregory called from the hallway outside the boardroom.

“It’s chaos,” he said, a whisper that sounded like a shout. “Preliminary findings presented. Three board members have resigned on the spot. They’re not even pretending they didn’t know. David is claiming he followed established practices. No one buys it.”

By noon, a press release: leadership restructuring, cooperation with regulators, “commitment to transparency.” Four board members resigned, including William. David Langston: terminated for cause. The stock chart made a new valley.

When the interim CEO asked to meet, I agreed on the condition that we do it at Barbara’s office. Patricia Donovan arrived looking like a woman who hadn’t slept in a bed she trusted in days.

“I won’t waste your time,” she said. “The company is in crisis. You’re at the center of it—not because you did anything wrong, but because you were the only one who consistently did the thing everyone else avoided.” She slid a folder across the table. I stared at it without touching it. Some objects never stop being symbols.

“This rescinds your termination and reinstates your employment retroactively,” she said. “Your pension is fully vested. There is an additional compensation package for the… circumstances.”

Inside: five years’ salary, lifetime healthcare, a formal apology signed by a board that didn’t exist last week. An offer to help design a new ethics division as a consultant after my retirement.

“And the people who did this,” I asked. “Beyond David.”

“Criminal referrals have been made,” Patricia said. “The company will not be defending them.”

I closed the folder. I didn’t say yes. I didn’t say no.

That night, I sat on my porch and watched the sun level itself behind the trees. The neighborhood kids rode bikes in circles that grew wider as they argued about whose turn it was to lead. I thought of Thomas, who used to tell me my meticulousness wasn’t a quirk but a superpower. I thought about the day Elizabeth learned to ride without training wheels and how she shouted, “Mom, look!” without ever looking back.

The whistle of a distant train carried across the evening. I slept like a person who had set a heavy thing down but still felt it in her hands.

Part 2

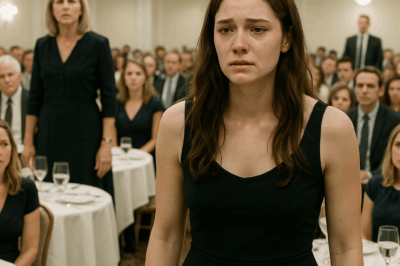

Six months later, I sat on a wooden pew in a federal courtroom that smelled like carpet cleaner and conviction. David walked in wearing a dark suit that had lost the performance of power—it looked like fabric, not armor. Two former board members followed. When the clerk asked for pleas, the words came out of their mouths like coins: guilty.

The man who slid a folder across a desk and tried to turn my life into a line item stood at the lectern, thinner around the eyes. Our gazes met. He didn’t see me, not exactly; he saw a consequence wearing a face.

The GRW scandal became a case study in the kinds of meetings that should have happened and didn’t, the reports that should have been read and weren’t, the quiet heroes companies underpay because they forget the cost of integrity is lower than the price of cleaning up without it. Business schools taught lectures about controls and culture. Journals quoted my memos because I wrote them in sentences that refused to be misinterpreted.

I declined the consulting role Patricia offered. I didn’t want to go back into the building where the walls remembered me only when I became useful to their defense. Instead, I worked with regulators to help design whistleblower protocols that made it easier for the next woman to pick up a phone without worrying she would lose her roof. The SEC awarded me a whistleblower share—fifteen percent of the penalties assessed against GRW—which felt like a check written by justice in a shaky but legible hand. Combined with my pension and the company’s settlement, it meant security I had never imagined. I used part of it to establish a scholarship for women entering corporate ethics and compliance. I named it after Thomas, who would have teased me about my inability to do anything halfway.

Elizabeth moved back to St. Paul with my grandbabies. We spent Saturdays at the lakeside house I bought with a porch that faces the water and the kind of kitchen drawer you can fill with measuring spoons you never knew you needed. We built the kind of memories you can only build when you’re not constantly half-listening for your phone.

One evening, while the kids tried to convince a dragonfly to be a pet, Elizabeth asked, “Do you regret staying at GRW all those years?”

I let the question sit. Regret is a heavy blanket; I refuse to wear it at the wrong season.

“No,” I said at last. “I regret that I had to expose them. I don’t regret showing up. Integrity isn’t telling the truth when it’s easy. It’s keeping your spine when the cost gets counted.”

“You taught me that,” she said. “Not by saying it.” She leaned her head on my shoulder like she did when she was small and thunderstorms were stories the sky told to itself.

GRW survived, smaller and sober. They sent me annual reports unbidden, perhaps as apology, perhaps as proof. I read them the way I always have—line by line, footnote by footnote. For the first time in years, the numbers and the story behind them told the same tale. Their filings began to contain sentences I recognized: “We did not do this correctly. We are correcting it.” Transparency is a language that can be learned.

People tried to turn my story into revenge, but revenge suggests that you burn the house down on purpose. I didn’t light a match. I turned on the lights. The people inside saw themselves and mistook illumination for flame.

In quiet moments, details return. The exact feel of the manila folder. Janet’s hand hovering over the stapler as if the right staple would bind the page to a future where it didn’t have to be read again. The security guard’s discomfort. The way the rain looked on the glass of David’s office, blurring my reflection into something I barely recognized. The way my kitchen table felt under my forearms when I sorted documents into piles that made sense like prayers do. The way the federal building elevator mirror always showed me a woman who had slept enough, even when I hadn’t.

During the long middle of the investigation, when days blurred into boxes checked and meetings attended, there were other moments, too. A handwritten note from a junior analyst in another company: Your story made it possible for me to send my memo instead of closing my laptop. A text from Janet: HR is different now. We’re remembering people are people. A postcard from a retired line worker at GRW: We always knew you were on the level. Coffee on me if I ever run into you at Midway. I put them in a drawer with rubber bands and pennies and the paper clips that refuse to be thrown away.

Not every headline was pleasant. When David gave the interview where he tried to rewrite my history into a vendetta, I learned that a lie told loudly enough calls other lies to it. I learned not to read comment sections on articles about myself. I learned that silence deployed strategically is not surrender; it’s strategy. I learned that time can be a friend if you feed it facts.

There was a day in early fall when I drove past GRW’s campus without meaning to. Habit has its own hands on the wheel. I parked in the visitor lot and sat with the engine off, windows down, air heavy with the smell of the foundry. Employees walked in and out of the doors I had walked through ten thousand times. No one looked up. That’s how you know a place is healing: it goes back to being unremarkable.

I didn’t go inside. I didn’t need to. I drove to the small coffee shop Thomas and I used to like, ordered something too sweet, and watched students fold laptops and unfold lives. I wrote a check to the scholarship fund and didn’t immediately regret the amount. I texted Elizabeth a photo of a dog in a sweater. She sent back three hearts and a picture of a child smugly holding a frog.

Months later, Patricia invited me to speak to GRW’s new ethics & compliance team at their first offsite. I hesitated. Then I said yes, but only with two conditions: that the session be open to anyone in the company, not just the people whose job title had the word ethics in it, and that I could speak about the years before the scandal as well as the days after. She agreed.

The room filled with engineers, assistants, machinists in work boots, newly minted analysts who still believed a spreadsheet could fix everything. I told them the story they already knew in pieces, and then I told them the one they hadn’t heard: about the nights when I wrote memos and printed two copies because I had learned where paper went to disappear; about the meeting where a VP told me I was “exaggerating variance” and how I had driven home, pulled into my garage, and cried for exactly thirty seconds before going inside to make dinner; about the boss two decades ago who put a gold star at the top of my report because he had a sense of humor and wanted me to smile; about how culture is the difference between a gold star and a manila folder.

During the Q&A, a machinist asked, “How do we know when to blow the whistle and when to try one more time inside?”

“You know because you try, and the door closes on your fingers,” I said. “You know because you start documenting to protect the company and realize you’re documenting to protect yourself. You know because you can’t sleep. When you know, call a lawyer before you call a friend. Call the agency before you call a reporter. And if you ever need someone to look you in the eye and tell you you’re not crazy, find me.”

Afterward, Patricia walked me to the parking lot. “You could have buried us,” she said. “Thank you for not doing that.”

“I didn’t save you,” I said. “I saved the part of you that can be saved.”

She nodded. “That’s enough.”

On the one-year anniversary of the day the folder slid across the desk, I baked a cake myself. It sank a little in the middle, which felt appropriate. Elizabeth and the kids came over with balloons that refused to stay knotted. We ate on the porch, plates balanced on our knees. The youngest asked what pension meant, and Elizabeth said, “It means Grandma kept a promise to herself until other people had to keep theirs.”

After everyone went home and the house settled, I took the apology letter from GRW out of the folder Patricia had given me and read it again. It didn’t feel vindicating. It felt… administrative. I slid it back into the folder and put the folder on a shelf behind the puzzle with the missing piece and the set of napkin rings we never use. Not because I wanted to forget, but because memory is lighter when you don’t carry it around the house.

A week later, a package arrived: the first annual report of GRW’s new ethics division. On the cover, a photograph of a steel coil and a headline: The Truth Is Cost-Effective. I laughed out loud, alone in my kitchen, because somewhere, a copywriter had either become a poet or hired one.

I still have the lockbox. I still keep copies of things other people lose. But the box doesn’t feel like insurance anymore. It feels like a habit I might someday unlearn.

Sometimes I imagine a version of my life where David didn’t slide that folder, where my last Monday at GRW was cake and candles and a speech from William about the value of long service. I try to feel sad for the version that never happened. I can’t. The life I have is the one I made when I lifted a phone and said the first sentence out loud, the one where I looked at paper and chose to believe it even when people told me not to. The life where my daughter says to her children at the playground, “Your grandma is brave,” and I don’t correct her. The life where the maple outside my window turns the exact color of courage every October, and I say thank you to a tree.

Three days before my pension vested, my boss fired me with a manila folder and a speech about budgets. I made a phone call.

What came after wasn’t revenge. It was arithmetic. It was process. It was proof stapled to proof until the weight of it bent a table. It was an old habit—tell the truth—done loudly enough that the world had to learn a new one—listen.

And on a quiet evening, when the sun goes down behind the lake and the air smells like rain that might or might not arrive, I let myself feel the simplest sentence in the world settle in my chest.

I kept my promise to myself. And that was enough.

END!

News

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left. CH2

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left Part One In…

At Dinner, My Sister Called Me A ‘POOR TRASH WORKER’ — Then A Guest Asked, ‘WHAT’S THE OWNER DOING?’ CH2

At Dinner, My Sister Called Me A “POOR TRASH WORKER” — Then A Guest Asked, “WHAT’S THE OWNER DOING?” …

I found out my husband had a mistress in a rather unexpected way my shampoo was running out way too fast! CH2

I found out my husband had a mistress in a rather unexpected way… my shampoo was running out way too…

My family texted “We need space from you. Please don’t reach out anymore. At all” CH2

My family texted “We need space from you. Please don’t reach out anymore. At all” my uncle packed them up….

During breakfast, my daughter said, “I have a surprise for you.” CH2

During breakfast, my daughter said, “I have a surprise for you.” She handed me an envelope. Inside was her husband’s…

My husband left me in the rain, 37 miles from home. He said i “needed a lesson I didn’t argue i just watched him drive away. CH2

My husband left me in the rain, 37 miles from home. He said i “needed a lesson I didn’t argue…

End of content

No more pages to load