At the Will Reading, Dad Smirked With His Mistress — But Grandma’s Final Wishes Changed It All

Part One

It was pouring the kind of cold, relentless downpour that makes the air itself heavy. Water lashed my windshield in sideways sheets, the wipers groaning with each pass as if they, too, were tired. I sat with my hands locked on the wheel, staring at the gold-lettered sign: Whitman & Ellis, Attorneys at Law. The building loomed between Greystone Towers in downtown Boston, windows glowing against the storm like watchful eyes.

“My name is Camille Bennett,” I told myself, the way you steady your breathing before a march. Thirty-seven. Marine. Daughter. Today I was walking my mother into the room where my grandmother’s will was about to be read. The shape of that sentence tilted everything. Margaret Bennett had died four days ago, and even saying it inside my own head felt like knocking on a door that wouldn’t open.

“I’m ready,” I’d told my reflection that morning, smoothing the lapels of my dress blues, whispering steady words to the woman with water in her lashes. The uniform felt like armor, but the rain had found the seams anyway, seeped in, clung. When my mother reached across and rested her trembling fingers on my arm, I swallowed the useless words and found the truth instead.

“We do this for her,” I said.

Margaret wasn’t my mother by blood, but when blood failed to do its work, she had been the one to mother me. Quiet listener. Steady presence. She stood between me and my father’s hard silences, gave me tea when my marriage shattered, left the porch light on when my shame made me slow to lift a hand. She didn’t judge. She didn’t fix. She saw.

I pushed the door open. Rain bit like teeth. My heels clicked against slick stone; my mother’s smaller steps fell into rhythm with mine. We climbed. And then we saw him.

My father, Richard Bennett, dry as an oath under the overhang, not a drop on his immaculate navy suit. Silver hair combed back. Tie knotted with that same precision he’d demanded from me at eight when he tutored me in optics, not ethics. His face was smooth and faintly amused, a mask he wore as easily as breath.

At his side stood Sierra James, twenty-seven, the mistress I’d known about in the way daughters know everything they are not supposed to know—perfume that wasn’t my mother’s, late nights that pretended to be business dinners, a new cologne that arrived in the house like an announcement. Seeing her here, pressed against him with a newborn in her arms, felt like walking into a door I knew was there and breaking my nose anyway. Her dress clung the way a statement does. Her lipstick was untouched by the weather. She curled herself closer to him and tilted her head on his shoulder as if this were a celebration, not the moment we were burying my grandmother’s voice in legal paper.

She smiled at me across rain-slick marble: bright, polished, edged with triumph. He met my eyes with that look he’d perfected near the end of my marriage—a look that turned me into background noise he could turn down with a glance. He adjusted his cuff links and tightened his smirk.

Almost, I turned around. Almost let the storm swallow me. But then I felt it—a remembered squeeze of fingers in mine, my grandmother’s voice tucked into a spring afternoon: You’re stronger than you think, Camille. I tightened my grip on my mother’s arm. Her head lifted. Her lip trembled, but she didn’t.

We walked past them without a word. Past the smirk and the small sleeping face Sierra rocked like a prize. Past the silence pressing on my spine from people who always believed the room belonged to them.

Inside, warmth rushed over us with the smell of polished wood and coffee. The receptionist looked up, her voice smooth and practiced: “You’re here for the Bennett estate.” I signed Camille Bennett on the clipboard, no hyphens or qualifiers or parentheses to explain me.

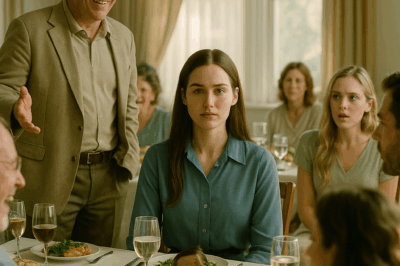

The hallway stretched long and hushed, carpet thick under our feet, sconces casting amber pools on dark oak. It felt less like a place to grieve and more like a corridor leading to judgment, which, in a way, it was. The assistant pushed open double doors and ushered us into a conference room built to intimidate: leather chairs with high backs, a mahogany table long enough to seat a battalion, shelves lined with leather spines no one had touched in decades.

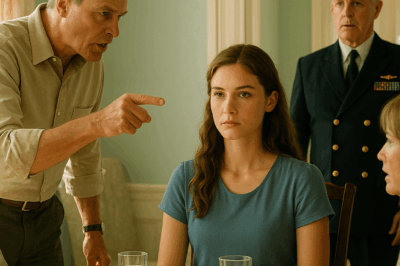

I chose a seat at the side. My mother sat beside me, her hand finding mine under the table, fragile but firm. Across from us my father leaned back like a king in his temporary court, ankle resting on knee, fingers tapping against polished wood in a rhythm he used when cameras weren’t rolling but he wished they were. Sierra nestled at his elbow, the infant swaddled in white against her chest. “Camille,” she said sweetly, tilting her head. “You look well.” I gave her nothing.

The door opened again. Mr. Harold Whitman entered with a leather briefcase and silver glasses that glinted under the chandelier. He shook the rain from his coat with a small, neat gesture and took the chair at the head. He placed a thick folder on the table with the care you use for something that could explode.

“Thank you all for coming,” he said, voice steady, low. “Shall we begin?”

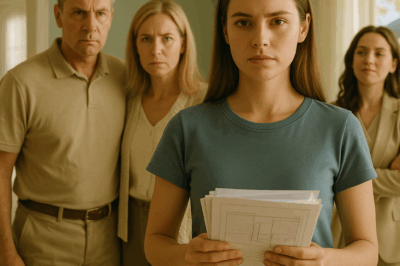

Before he opened the folder, my gaze snagged on a smaller envelope: cream-colored, edges worn, my name written in my grandmother’s unmistakable slanted script. It sat half-tucked under the legal packet, quiet as a witness. The room hadn’t noticed it yet. I had. Every part of me leaned toward it, but Marines don’t reach for things until they’re told to. I let my hands rest open on the table and felt my pulse in my throat.

“We are here for the formal reading of the last will and testament of Margaret Elizabeth Bennett,” Whitman began. He glanced at each face in turn. “Mrs. Bennett prepared this document six weeks prior to her passing. It is legally binding.”

Sierra leaned forward, smile brightened by calculation. “Mr. Whitman, just to be clear, Margaret made her wishes very clear to Richard. This shouldn’t take long, right?” She adjusted the baby so that an embroidered crown on the blanket flashed in the chandelier’s light. My father’s hand slid over hers and squeezed. His other hand drummed a soft, satisfied rhythm on the wood.

“Everything will be addressed in the will, Miss James,” Whitman said, polite as a closed door.

He paused, closed the folder halfway, and rested his palm on the cream envelope. “Before I proceed, Mrs. Bennett left a sealed personal letter to be read aloud after the will is fully disclosed.” The sentence fell into the room like a stone into a pond. Ripples spread. Sierra’s smile trembled. Dad’s smirk twitched, then faltered.

“It’s nothing,” Sierra whispered to him. “Something sentimental.” Her hand trembled slightly against the baby’s blanket.

I straightened, boots braced in carpet. Silence carries its own weight when you let it. I let it now.

The legal language began its measured march: being of sound mind and disposing memory… revoking all prior wills… executor to serve without bond… assets enumerated by institution and last four digits. Beacon Hill. Lakeside cottage. Investment accounts. Jewelry. Digital assets. Words that glittered at a distance and couldn’t warm a room. The rain battered the windows like applause for a play I wasn’t watching.

I drifted to the sunroom in my grandmother’s house, to tea in thin cups and a tin with ginger-lemon cookies, to a documentary about glaciers moving at a speed that couldn’t be hurried or argued with. They don’t move to please anyone, she’d murmured. They move when they must. And then one morning the whole map is different.

“Let the record reflect,” Whitman said, pulling me gently back. “Mrs. Bennett also executed a bequest memorandum regarding personal effects and letters.” His hand moved to the envelope as if to remind me: I saved the last words for you.

“Proceed to allocations,” my father cut in, and Whitman’s mouth bent into the smallest smile—the way a man smiles when someone forgets the order of operations in a process he invented.

He turned a page. “To my beloved son, Richard James Bennett, I leave the portrait of his late father currently displayed in the study of my Boston home.”

The words landed velvet-wrapped and sharp as a needle. Dad blinked as if he’d misheard. “The portrait,” he repeated, tasting it and finding it beneath him.

“To Miss Sierra James,” Whitman continued, “no specific bequest is made.”

Color drained from Sierra’s face, gloss stiffening on her mouth. She tightened her hold on the baby. My father made a low, strangled sound in his throat.

“And to Camille Anne Bennett,” Whitman said, voice clear and carrying, “I leave the entirety of my estate. The residence at Beacon Hill, the lakeside cottage in Vermont, all investment accounts, all heirloom jewelry, and any remaining physical or digital assets.”

Silence pressed down until my ears felt it. My mother’s fingers crushed mine in a brief, painful squeeze and then softened into a steady anchor. Sierra snapped her head from the baby to Richard to Whitman as if one of them might blink the words away. My father’s chair screeched as he leaned forward.

“Read that again,” he demanded.

Whitman’s tone didn’t change. “To Camille Anne Bennett, the entirety of the estate.”

“This is absurd,” Dad snapped. The polish on his voice chipped; the old anger showed through. “Margaret would never. She knew her duty. This family—”

“—has a will that was witnessed and notarized six weeks before her passing,” Whitman said, steel sliding under courtesy. “I have the certifications if you wish to review them.”

“She told us,” Sierra blurted, desperate now. “She told me that Logan would inherit.” She jostled the baby—Logan, then—forward like evidence. “She said the name had to carry on.”

“The contingency clause is clear,” Whitman said. “If Ms. Bennett declines, the estate goes to the Willow Creek Literacy Foundation.”

The name stood up in the room and stretched: Willow Creek—the town my grandmother spoke of when snow fell and she told me about a little library with a bell above the door and warm light in winter. She’d once said the only place she felt like herself was on the rug by the children’s section, reading until the librarian kicked her out gently at closing.

“So either she takes it,” Sierra said, stabbing the air toward me, “or it goes to some… library?”

“A foundation for literacy,” Whitman corrected.

Dad stood so fast the chair toppled. “Unacceptable. My mother would never choose—”

“She did,” Whitman said, the word stopping him like a hand on the chest. “She chose clearly.”

My mother made a sound then—a small, broken thing unspooling from the center of her. It wasn’t delicate. It wasn’t polite. It was honest. She bowed her head, pressed a trembling hand to her mouth, and cried—bent forward with the weight of grief and relief and the kind of truth that pulls the pins out of a life. I wrapped an arm around her and held on. Across the table, Sierra froze, mid-bounce, the baby’s tiny whimper echoing her shallow breath. My father’s face moved through red toward gray.

“Mrs. Bennett asked that this letter be read aloud,” Whitman said softly. He slid the opener under the cream flap and lifted a single thick page. The ink was a deep, decisive blue. He began.

My dearest Camille,

If you’re hearing this, I’m in the sunroom in my mind, shawl on, chamomile in the good china I never saved for special days. I picture your hands folded the way you do when you decide not to tremble. I know that look. I wore it once.

I’ll be plain. I did not do what I did to hurt Richard. I did it because I can no longer protect a version of him that only lived in my hope. He chose charm over honesty, control over kindness, performance over truth. That broke my heart. Hearts survive their own breaking.

Richard exhaled the old tell when someone failed to follow his script.

As for you, Camille: quiet is not the same as small. When you stood in my doorway with rain on your lashes, apologizing for taking up space, I saw a woman who had learned to live in other people’s weather. I wanted, for once, to give you a roof of your own.

You never asked for anything. You didn’t weaponize your wounds. You worked. You noticed gentleness. I trust that more than anything I could leave you. So, I decided not to reward you, but to free you.

Sierra looked down at the baby, then up, blinking fast, her composure slipping like a silk scarf from a shoulder.

I know about evenings in a house where your name had to ask permission to be spoken. I know about perfume that wasn’t yours and trips explained with a smile as if that were enough. I know you were called dramatic for noticing. I am old enough to say what younger women are punished for saying: it was not in your head. I also know you kept your dignity. I watched you set your jaw instead of your house on fire.

Richard, if you are listening—and you are here—is a final gift that is not an object: charm is not character. Applause is not love. Control is not care. A mother cannot make a man out of years he refuses.

My father stared at the table. His hands had stopped moving.

There is a portrait of your father in the study. You have always liked how it looks. Take it. It belongs with you. As for the rest, I put it in the hands that never asked. If Camille declines, it goes to the library that raised me when money didn’t—the Willow Creek Literacy Foundation. That building kept me company when my house felt too small. It will keep other girls company after we’re dust.

Camille, houses and accounts are poor substitutes for courage. But sometimes they buy time, and time is the currency of becoming. Use it. Waste none of it convincing people who are busy being unconvinced. Spend it on building, on quiet, on friendship that survives an empty room. Paper is only as brave as the hands that carry it. Carry this well. Not for me—for yourself.

My mother laughed inside a sob the way you do when a verdict finally fits.

You will be tempted to apologize as you choose. Don’t. The people who love you will not require a receipt. Keep those people. The rest will wander off when your boundaries stop feeding them.

When your father tells a story about legacy, remember: legacy is a verb. Being believed is a form of shelter. You may insist on it. I ask that this be read aloud because I have watched the truth negotiated into something polite. Consider this my last impoliteness and my best manners.

I loved you, Richard, as mothers love their sons. I am not withdrawing that love. I am refusing to mortgage anyone else’s life to it.

And you, Camille—there’s a pie recipe behind the flour in the second cabinet. It isn’t very good. Add more butter. Don’t be stingy with cinnamon. Serve it warm to someone who had a long day. If no one has, serve it to yourself. Don’t keep my teacups on a shelf. Drink from them. Let them chip. That is how you know a thing has lived.

Quiet women carry heavy truths. Set them down where they can rest.

Yours, unabashed and unafraid,

Margaret

No one applauded. The rain softened on the windows. Whitman folded the page once, twice, and handed it to me. I slid it back into the envelope and felt its weight—small enough to misplace, heavy enough to anchor a life.

“This is theater,” my father rasped. “She—” He ran out of verbs.

“It was a will,” Whitman said, courteous and immovable, “and a letter.”

“You won’t get away with this,” Sierra said to me, brittle as glass. “We’ll contest.”

“You can try,” I said. “You’ll lose.”

My mother lifted her damp face. “She saw you,” she whispered. “She saw us.”

“I know,” I said. And I did. It was like turning on a lamp in a room I’d always walked through in the dark and seeing familiar furniture as if for the first time.

Whitman capped his pen. “Unless there are process questions, we are concluded.”

There weren’t. Sierra stood so fast her chair scraped. The baby cried. She flinched and threw my father a look edged with blame. He reached for her elbow; she shrugged him off. They left without looking back.

I offered my mother my arm. She took it, not because she was weak, but because the day had asked her to be carried for once. We stepped into the hall, into the warm hum of carpet and sconces and breath. When the elevator doors closed, I caught a last glimpse of the long table and the shelves of books no one read, the place where a kind woman’s last words had made a room remember itself.

Outside, the air smelled of wet stone and freedom. I opened the umbrella and tilted it over my mother. The rain that had felt like a wall on the way in felt like a washing now.

We stepped into it together.

Part Two

We didn’t speak much on the drive. Boston slid by in slick ribbons of light. Headlamps cut through puddles like thrown coins. Neon bled on the asphalt. I let my hands be steady on the wheel while every muscle in me hummed with the echo of a woman’s voice that was gone from the world and more present than anyone I could have invited to a table. Quiet women carry heavy truths. Set them down where they can rest.

When I pulled into my mother’s drive, her shoulders curled inward in that old reflex of making herself smaller around a man’s choices. Justice for me had come with a price for her: she had lost a mother, and the last illusion about her husband had been excised with expert hands. The porch light sliced familiar gold across the wet siding. I put the car in park and turned toward her.

“She gave it to you,” she whispered, voice raw. “She gave you everything.”

“She gave me a chance,” I said. “I’m not taking it away from you. Half is yours.”

She flinched like I’d thrown a number at her. “I don’t want—” The sentence broke.

“I know what you want,” I said. “To know she saw you. She did. But she wanted peace for you. Money is only paper until it buys time. Let it buy you time.”

Her mouth trembled. “I thought I was the fool.”

“You weren’t,” I said. “You stayed. There’s a different kind of courage in that.”

We let silence do the good work—the kind that isn’t punishment but rest. The rain softened to a steady whisper on the roof. She squeezed my fingers briefly, then reached for the door.

The next days blurred into appointments and signatures and certified letters with embossed seals. I moved through them like a field manual: read carefully, initial here, sign there, note the contingency. The Beacon Hill townhouse sold first, just as it had once impressed neighbors from the stoop—the address carrying more weight for buyers than warmth had ever carried there for me. Numbers landed in accounts that had never seen such commas. I wired half to my mother. She tried to refuse. She cried when it cleared. “It’s like she gave me back time,” she said. I believed her. It felt like time.

Storms don’t vanish. They hover. Three days after the reading, my father knocked on my apartment door with drizzle flattening his hair and a suit that had been tailored for a different man. No umbrella. No stage. Just a damp shape of the person who had once taught me to tie a tie for a uniform he wouldn’t bless.

“Camille,” he said. The softness in his voice was more unsettling than his rage. “We need to talk.”

“We don’t,” I said.

“I didn’t know she’d do that,” he said. “To you. Of all people.”

“Why not me?” I asked. The question was a knife I’d been sharpening for years.

He blinked, then said the quiet part out loud. “Because you’re not… family.”

The word had once bruised me for weeks. Today it dropped to the floor and rolled under the console table and disappeared. “She didn’t see it that way,” I said.

“You’ll give it back,” he pushed, panic showing through the practiced veneer. “You’ll do the right thing.”

“You mean hand it over so you can parade it at golf clubs and boardrooms, so she can raise her child in a house you didn’t build while Mom sells her wedding china to pay the oil bill?” I kept my voice level because I’d learned yelling only feeds certain men.

He flinched. He looked older with each breath, as if the air took something from him he didn’t know how to keep. “The business is failing,” he confessed, the sentence small. “Sierra took the baby to Austin. She… doesn’t answer my calls.” He blinked fast, and for a second I saw the man I had wanted him to be.

“You have something left,” I said. His face tilted toward hope. “Consequences.”

He staggered back as if the word had hit him in the chest. “I don’t know who I am without all of it,” he said.

“That’s not my work,” I said. “That’s yours.”

He lingered in the threshold like a boy waiting for permission to run when everyone else had already started. When I didn’t give it, he nodded once—defeat without drama—and walked into the rain.

I leaned against the door and let my breath arrive in my body. For years I’d believed healing would come when he finally apologized. Turns out you can live a whole life without the apology if you stop waiting for it to open the door you already have a key to.

A thick envelope arrived a week later. Official seals. Heavy paper. Deeds and titles and account summaries. I set it on my table and moved around it as if the act of ignoring it could make the decision for me. I made coffee. Stared out the window at a city that pretended not to notice storms. Straightened a picture frame. Finally, I slit it open.

Her signature rode the lines—decisive blue ink. Addresses lined up like stepping-stones. 114 Maple Street, Willow Creek. The name felt like a key turning in a soft door. Grandma had always spoken of it when the weather turned and the kettle boiled—bare feet on Main Street, a bell above the library door, a librarian who smelled like paper and cinnamon.

I drove there. The air felt lighter than Boston’s, even under clouds. The town had one blinking red light. The diner smelled the way diners should. Across from a shuttered post office and a bakery that only opened Sundays, I found a dusty storefront with a faded sign: Books & Brews. The window glass was cold under my palm. Bare shelves leaned like old men. The floor sagged. A strip of light made a humble altar across the back room.

Most people would have seen ruin. I saw space.

Wayne—calloused palm, kind eyes—met me in the diner with a contract and surprise. “That place?” he asked. “Why?”

“Because it’s mine,” I said.

By week’s end, it was. No fanfare—just a handshake over coffee and a name written on a line that mattered more than any I’d signed in a uniform.

The first day I cleaned it, my body hurt in ways field PT hadn’t even considered. I wore jeans soft with age and a sweatshirt that remembered bonfires. I swept cobwebs until my shoulders complained, scrubbed baseboards, sanded scarred counters. Wayne introduced me to Jacob, who smelled faintly of cedar and coffee and spoke with the quiet men save for when they know you need a laugh. We tore out rot. We built a new counter from reclaimed barnwood, sanding until the grain came up under our palms like memory.

“You sure about the name?” he asked, skimming his thumb along the edge.

“The Hearth,” I said. Not Books & Brews. This wasn’t about products. It was about warmth.

He looked up at the honey-colored paint I hadn’t been able to resist. “Yeah,” he said after a beat. “That’s a good kind of place.”

The menu came from recipe cards my grandmother had written in that same blue ink that signed legal documents and mothered girls who weren’t her job. Orange Zest Muffins—double batch—add a pinch of clove. Trust me. The first three attempts were disasters for different reasons. The fourth rose just right and split like sunrise. I broke one open. The steam carried citrus and cinnamon into the morning. I heard her voice: more butter. I added more butter next time.

We opened on a Wednesday without telling anyone but the town’s group chat, which meant everyone knew. The bell over the door chimed like memory. The sisters who taught piano for forty years split a slice of pie and pretended not to cry. A night-shift nurse in scrubs bought two scones—one for now, one for later. A teenager with tired eyes and calculus homework stirred whipped cream into cocoa and stopped shaking his leg.

They didn’t ask who I used to be. They saw who I was—a woman with flour up her sleeves building a room that asked nothing except that you sit for a while and be.

He came on a Thursday, when mist hung low against the windows and the town seemed to breathe quieter. He stood across the street for a long time like a man who needed to be told go on but knew the days of being told had ended. He crossed. The bell announced him. The room thinned in that way rooms do when they sense something important about to bruise or heal.

“You did all this?” my father asked, voice small.

“Yes,” I said.

“It’s beautiful,” he said, and I believed him. His hands shook when he shoved them deeper into his pockets. “Camille, I’m sorry.”

“This place isn’t for that,” I said.

“I’ve lost everything,” he said without his old drama. “The business. The house. Sierra. She took the baby. She—” His voice broke. “I don’t know who I am without all of it.”

“You still have something,” I said, wiping my hands on a towel.

“What?”

“A chance to be someone you have to live with,” I said. “That’s harder than being someone other people watch.”

He waited for me to throw him a rope. I didn’t. Marines don’t rescue men from ships they set on fire. He nodded like he knew that was the answer before he asked. The bell chimed when he left. The room exhaled.

That evening my mother came in with a library book and sat by the window. I put a muffin in front of her with butter melting across the split. “More butter this time,” I said. She laughed through tears. “She’d be proud.”

“I know,” I said. And for once I did.

The money made things easier—the kind of easy that doesn’t fix grief but gives it a chair and a warm drink. We sold the cottage in Vermont to a couple who brought their shy dog to the closing and cried in the parking lot. I kept Willow Creek. I gave half of everything to my mother without ceremony and watched her buy a car that started without prayer. The remaining money became work: grants to the literacy foundation my grandmother loved, donations to the library that had kept her warm, seed money for a reading program tucked into our back room for kids with nowhere soft to land after school. A sign over that corner reads: Quiet is not the same as small.

People ask sometimes—quietly at the counter, halfway through their coffee—if this was revenge. I tell them no. Revenge wants someone else’s defeat. What I wanted was a life I didn’t have to apologize for. What I wanted was a room where I could set down what I’d been carrying and watch other people do the same.

One afternoon a girl about nine wandered in, hair damp from rain, a library book under her arm. She counted out change with serious fingers and asked if she could sit without ordering because she liked the sound of the bell and the smell of orange. “Of course,” I said, sliding a muffin across the counter like an accident. She took a bite and her eyes went wide. “I didn’t know places like this existed,” she announced.

“They do now,” I said.

At closing, I washed cups with chips along the rim and stacked them imperfectly on the shelf. My grandmother had told me not to keep teacups on display, that life should scuff what we love or we never know we really used it. The bell’s last chime drifted into the street. I turned the sign. The town kept breathing.

On the wall across from the counter, a small framed thing hangs—cream-colored paper with blue ink. A copy of a paragraph from a letter, not the whole thing, just enough to hold:

Paper is only as brave as the hands that carry it. Carry this well. Not for me—for yourself.

Customers ask sometimes who wrote it. I say, “A woman who knew me before I did.”

When I walk home at night, Willow Creek is all wet leaves and the hush of a place that trusts morning to come back. I unlock my door and hang my coat and line up my boots and touch the letter in my bag without needing to take it out. I make tea in my grandmother’s good cups and chip them by accident on purpose. I add too much cinnamon to pie and call it a choice. I phone my mother to ask about nothing.

A year after the will reading, I drove to Boston with a trunk full of books the library in Willow Creek didn’t have room for and set them in the donation bin at the public branch a few blocks from Whitman & Ellis. On the way back, I walked past the old townhouse and didn’t feel anything heavier than weather. The city smelled like wet stone again. The rain hit my face like a benediction instead of a warning.

I won’t pretend every day is soft. Some mornings I reach for a sleeve that isn’t there and find grief instead. Some afternoons I write my grandmother’s name in flour on the counter and wipe it away quickly like you do with magic you don’t want to waste. Some evenings my father’s shadow passes the front window of The Hearth and keeps going.

But most days, a bell rings and someone steps into warmth and sits down and orders something small that is also exactly enough. Most days, I don’t have to convince anyone I’m not small when I’m quiet. They know because the room I built speaks the truth out loud.

If you’re still with me—if this story pulled you through rain to a table and set a cup in front of you—then take this part home: sometimes the map changes not when glaciers roar, but when they keep moving at a pace that doesn’t require permission. Sometimes the will isn’t the paper a lawyer reads; it’s the choice you make after. Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is let a woman’s last words undo the ones you lived under too long, and then build a room where other people can set theirs down, too.

I come from a line of quiet women who carried heavy truths. We’re setting them down now. We’re making tea. We’re adding more butter. We’re not being stingy with cinnamon.

The door is open. The bell knows your name.

END!

News

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

My Parents Demanded I Sell My House to My Sister or Be Disowned—But Her CEO Already… CH2

My Parents Demanded I Sell My House to My Sister or Be Disowned—But Her CEO Already… Part One My…

End of content

No more pages to load