At the Mansion, I Froze in Shock Seeing My Husband—Who Had Been Missing for 2 Years…

Part One

The air in Boston that October felt unreal—thin and clean, ribboned with the smell of leaves and woodsmoke, as if the city itself were blessing us. The afternoon sun turned the river to hammered copper, and the wind carried laughter up and down Commonwealth Avenue like a promise. That was the day I became Mrs. Emily Parker Whitmore.

People tell you wedding days blur. Mine didn’t. I remember the weight of crystal in my hand and the way the ballroom lights fractured into starbursts when I turned my head. I remember the warm skid of a perfect shoe on polished parquet and my mother’s emotional little gasp right before the music swelled. But it’s Daniel’s hand that lives in me the clearest—warm and sure and exactly the right size for mine, steadying me at the altar as if he’d been practicing for this moment his entire life. When we exchanged vows, he looked at me like I was the only person left in the world.

We’d had three years to rehearse that look. Three years of stuffing our pockets with thrifted paperbacks and walking along the Charles at midnight, of cheap takeout eaten on stoops between double shifts, of carefully planned weekends in Maine when we were flush and carefully rationed Netflix when we weren’t. When he proposed—on a footbridge after a spring rain, kneeling in a puddle without noticing because he had a speech to get through—I didn’t hesitate. Everyone else saw incandescent romance. I saw the safest place I’d ever known.

The first years of our marriage were small and golden. Our apartment was the kind you learn to move around without bumping elbows, the bathroom you learn to share like diplomats. I bought candles for every season because I wanted the air to feel like a decision. He stacked case files on the kitchen table and under the couch and once on the oven when he needed the other surfaces for “triage,” then laughed when I scolded him and carried the pile away, knowing my scold was part of the ritual. He’d come home late from the firm, kiss my hair, and ask about my day with that total, undivided attention that makes you say more than you planned. On Saturday mornings we walked through the Common with paper cups of coffee and pointed out dogs we would adopt when we had more room, more time, more everything. We were bank-account careful and time-rich and, yes, blessed.

If Daniel ever raised his voice, it was at the TV during playoff season. If he ever sulked, it was because I had beaten him at Scrabble with a suspect triple word. When things went wrong—not if, the world said, when—he met them with this wry, improv-calm that made me feel like nothing would ever be bad for long. A missed train became a chance to explore a new bakery. A thunderstorm on a beach day became a reason to watch the ocean in fury, the kind of memory you tell on rainy days. “We’re okay,” he’d say, which is the only spell I have ever seen work every time.

So when he came home one night with that particular light in his eyes—the edge-of-a-cliff light—I put down my fork and sat up straighter.

“I’ve taken on a case,” he said. “Not like the others. This could define the next decade.”

His client was one of those men people name libraries after. A face that appeared above business headlines. Real estate holdings like a map of the city. The case: a divorce with assets that sounded like hyperbole—estate portfolios, warehouses of art that had to be cataloged by specialists in gloves, towering accounts that moved in dozens of currencies. And the wife? “Relentless,” he said, grimacing. “Demanding, manipulative.” I winced at the sourness in his voice. Daniel is careful talking about opposing counsel. He is careful about words, period. To hear contempt was to hear thunder.

“Are you sure?” I asked that first night while he sketched timelines on legal pads. “It sounds… not just exhausting. Dangerous.”

He reached across the table. His palm covered the back of my hand. “This is what I trained for. It’s not about money; it’s about justice. He built all of it. She wants half of everything.”

The case consumed him. The kitchen table became a war room. We lived around exhibits and depositions and schedules of assets that read like inventories of small countries. He was gone before light some mornings and came home long after it. At night, he told me stories with names removed—marble kitchens that had never known cooking, antique diamonds bought by men who had no idea what they meant, a woman who auditioned new lawyers like stylists because she liked how power looked on her, dangling from her wrist. I started to hate a person I’d never met.

When they finally sat down across from each other—a conference room table smooth as water, witnesses arranged like chess—he shredded her platform. He was clinical, kind even, the way surgeons are kind when they lay out facts that will hurt you. Most of the assets had pre-dated the marriage. The business had been built before she met him. There were prenups with signatures and dates. There were affidavits with handwriting that slanted with impatience because wealth creates its own weather. “She’s asking for a life she never built,” he told me that night, laying his head on my lap. “And I think I convinced her it’s a rental.”

She agreed to terms the next afternoon. An apartment, a stipend calibrated to the jawline of her habit—but not a kingdom. Daniel called me in the stairwell, relief like laughter in his voice. “Papers tomorrow. Then I’m coming home on time. I want to sit at our own table and not think about anyone else’s.”

I went overboard. I bought his favorite wine. I brined a chicken. I lit candles and put on a playlist and moved the stacks of legal pads to a chair and sat there in a pool of warm light and thought about how we had weathered this together.

The phone rang fifteen minutes after he told me he was leaving the garage. “Just hit traffic,” he said. “Fifteen minutes.” I tucked a napkin under a fork and kissed my own finger for luck.

I never learned to measure fifteen minutes like that.

When twenty passed, I called. Straight to voicemail. I tried again at thirty. I texted, then called the parking garage. “He left twenty minutes ago,” the attendant said. “Bright blue tie? Good tipper? He waved.”

I ran to the street, absurdly, as if he might round the corner carrying flowers and an apology and we would laugh and go upstairs and life would unpause. The city was all wrong—too loud, too bright, too indifferent. The cold smelled like pennies.

My parents came. The police came. They took notes and descriptions and my voice with them. “Adults can disappear,” the detective said gently, as if good intentions make up for bad sentences. We canvassed security footage and benches and hospitals. We printed posters. We hired a private investigator who had a voice like gravel and eyes like patience. We took shifts sleeping and not sleeping. The chicken sat on the table like humiliation. In the morning, the kitchen looked the way hotel rooms look when you wake from a dream you can’t crawl back into.

People talk about grief in metaphors. The bottom dropping out. The ground turning to water. For me it was blackberries—how they stain your fingers for days. I couldn’t scrub it out. I tried to work for a week and found my hands shaking over copyedits, wove whole campaigns around phrases like vanish and return and felt like a monster when I caught myself. My parents found me kneeling in the shower one morning fully dressed. I remember my mother’s lipstick—coral, the kind she thought made her look less tired—and the way my father kept smoothing the same corner of the bath mat as if a crease could hold me to the world.

The hospital didn’t feel like failure; it felt like being picked up from the bottom of a pool. They gave me edges and pills with names that sounded like flowers. Nights were worst—corridors quiet as wrong decisions, nurses with ghost-step shoes. A counselor with hair the color of coins said, “You can drown or you can float. You don’t have to swim yet.”

When I left, I didn’t go back to the office. I couldn’t sit inside the architecture of my former life where every object testified against me: his mug with the chipped handle, the suit jacket that remembered the shape of his shoulders. I needed a different geometry.

Work found me instead. An elderly neighbor, Mrs. Henderson—who had postcards from New York tucked into mirrors and ballet posters taped over the dryer—needed help. I swept out corners and made soup and learned how to talk about anything but myself for hours. Mrs. Henderson told me stories of tours and aching feet and the way applause warms you differently than a lover’s hands, and I learned to be a pair of steady hands in a world that needed them. When she told me that grief is a dance you learn one step at a time—forward, back, pause—I believed her more than anyone else.

The city whispered my name back to me in odd places. In the produce aisle when I heard Daniel’s laugh two rows over and nearly dropped a lemon. On the T when a man in a suit smelled like his cologne and I stepped off two stops too early to stand with a stranger’s ghost. Loss is a neighborhood; you learn your way around it whether you want to or not.

People I cleaned for recommended me to their friends. I organized linen closets and shook out rugs and polished banisters I had no business touching because money had sealed their finishes like armor. Which is how I ended up at a townhouse in Back Bay that had columns like a courthouse and a door that weighed more than my car. Victoria Reynolds—whose name appears at the bottom of charity ball invitations as if it had been born there—owned the place. She hired me with an efficient smile and a once-over that told me she always knew the cost of things.

I was dusting the library shelves when I heard it. A voice in the hall: deep, warm, threaded with that court-trained patience like silk through canvas. It wasn’t Daniel’s, I told myself. It couldn’t be. Except my body didn’t know that. My heart, stupid, beautiful animal that it is, climbed the inside of my ribs like a ladder.

I waited. It was nothing. A guest. A cousin. A dream. Victoria called me back a few weeks later. I went because work is work and because I believe in not punishing the future for past hurts. This time I was in the kitchen when the door opened and the townhouse filled with expensive sound—leather soles on marble, the click of a watch clasp. I turned.

He walked in as if he owned the light.

Almost Daniel. That’s how my brain categorized him—the way you do with paintings at a museum when you see the original after years of postcards. The cheekbones were more pronounced. His hair was shorter, slicked back in a way that cost $85 and knew it. And then there was the scar: a clean diagonal just under the left eye like punctuation.

But it was his eyes that undid me—familiar shape, foreign weather. He looked at me. Past me. Through me the way men look through staff.

“Mr. Alexandrovich,” Victoria called, gliding into the room, vowels polished to a shine. “You’re early.”

Alexander… what?

The room stretched like a breath held too long. I said “Daniel” like a prayer that had missed its place in the liturgy and arrived late. He glanced at me the way one glances at a painting one has walked past a thousand times—polite, indifferent, nothing caught.

I finished the shift by muscle memory, my hands doing what they were told like hired ghosts. I went home and sat at my parents’ table with my fingers around a mug that didn’t cool because I wasn’t drinking. “It was him,” I told them. “But not.” They didn’t say you’re crazy. They said grief can do strange things to the eye, and I wanted to scream that grief had nothing to do with the unique way Daniel curled his fingers when he was about to make a point, or the pale crescent scar on his wrist from an old can opener, or the way his shoulders carried stress like a suit he was trying not to wrinkle.

The private investigator—whose gravel voice had softened when he saw me at the door because even professionals have hearts—took the case. He watched Victoria’s townhouse. He watched the man who now answered to “Dmitri Alexandrovich.” He watched them together like a director learning someone else’s blocking. Weeks later he brought me a report and a cup of bad coffee and, with the kindness of someone who hates his own news, told me a story.

Daniel had been assaulted the night he disappeared. Beaten near the Reynolds property. Found by Victoria. Taken in. He woke up a man without a name—no ID, no memory, only pain and a body that no longer felt like it belonged to him. Victoria wrapped him in a narrative: you are safe; you are Dmitri; your life starts now. Money can make paperwork where none existed. Faces can be introduced as histories. New suits can be hung in closets where old ones once hung.

Do I think she broke the law? Not obviously. Do I think she broke the universe? Yes.

I went to the police with everything I had: the timeline; the photos; dental records that matched because teeth don’t lie the way people do. A detective who had treated me gently two years earlier read everything twice and said, “We’ll look into this,” and this time I believed him because the paperwork landed differently on the table.

They brought Daniel—Dmitri—to Mass General for evaluation. I stood in the hall outside the interview room and remembered prom night nerves. My hands shook. My mouth tasted like pennies again. When they wheeled him in, he looked tired and expensive. When I said his name, the first syllable broke me in half.

“I’m sorry,” he said politely. “I don’t know you.”

The world did not end. It did not even make a sound. It shifted one millimeter and then another while I learned to breathe in the new shape. The doctors were kind. “Sometimes pictures don’t work,” one of them said. “Sometimes you need to stand in the exact place the memory is stored.” The next afternoon I drove Daniel to the garage where I had waited beside candles and a brined chicken and a future that had misread the schedule.

Concrete is honest. It keeps secrets only until the right feet walk over it. I parked in the same lane and turned off the engine and said, “Let’s walk.” At the far pillar Daniel’s body went stiff. He grabbed the rail as if the building had lurched. He made a sound I have never heard from a human throat, the kind wild things make when they remember traps.

“I remember,” he whispered, and then the words ran out of him like water from a smashed glass. Men in the dark. Fists. A boot. The taste of blood silvering his mouth. the cold slap of air as they dragged him across the floor. A woman’s voice later—low, rich, reassuring—telling him his name was Dmitri as if it had always been, telling him the past was a danger from which she, benevolent, had rescued him.

“I didn’t leave you,” he said into my hair.

“I know,” I said into his shirt.

The investigation picked up speed. The men who had done the beating were found because violence leaves receipts—burners and buddies and bravado. Under questioning they gave up the names of the people who had paid them. It wasn’t Victoria. It was the ex-wife’s family, furious at the settlement and feral with entitlement. They wanted Daniel silenced. They hadn’t planned the amnesia; they’d wanted a body. The universe refused their request and turned their violence into my husband’s second life instead.

There were indictments, hearings where men in suits pretended they hadn’t known what fists could do, paper that turned names into charges, and reporters who pelted us with questions like hail. We got him back on paper first. Birth certificate, license, passport: the prosaic liturgy of a life restored. Victoria fought, of course. In her story she had saved a drowning man, given him a name to cling to, a house to walk in without the echo of who he used to be. I do not hate her. I also do not absolve her. Charity is not custody. Love is not possession.

The judge ruled. He was Daniel again—legally, formally, out loud. Victoria’s face did something I have never seen a face do. It opened and closed like a door in a windstorm. It showed me the girl she had been before she learned money could hide her tender places. It showed me the woman who believed that keeping someone alive entitled her to keep him. She looked at me once like a woman measuring a cliff. I nodded because there are no winners here, only people who get to go home.

Daniel moved into my parents’ house first, then into the apartment we had kept because I am superstitious about mailboxes. He slept in the guest room for a while because familiarity can feel like a violation when you don’t own it. He was gentle with my expectations and impatient with his own memory. He wanted everything back at once. Neuroscience declined. He remembered in tatters—how he made coffee, how he folded socks, the last lines of novels. Our albums helped sometimes; the muscle memory of laughing in the kitchen helped more. You can’t talk someone into a life. You can walk them into it.

At night I found him standing at the window. “I owe her,” he said once, not looking at me. “She took me in when I was all… pieces.”

“You don’t owe her yourself,” I said, and this is where I could say something neat about boundaries and trauma and the rightness of justice, but the truth is that I cried in the shower a lot and I sat in the hallway listening to him breathe and I learned to say the same thing three different ways so his brain could catch it on a pass. The truth is that love felt like decision more than epiphany for a long time.

We went back to the garage together, weirdly, because that was where he remembered how to remember. Each time he found a new angle—the oil stain he had slipped on, the flicker of a fluorescent light that had been going out for months, the taste of metal. The brain is a house with too many rooms. You get lost until someone leaves the lights on.

When the men who ordered the attack were sentenced, the courtroom was colder than church. The judge was measured. The language was precise. The punishment was prison and fines and the rest of their lives hearing their names in the mouths of people who only say names in a certain tone. We walked out past cameras and someone asked, “Do you forgive them?” and I wanted to say, “I have better uses for my verbs.”

I will say this instead: I forgave myself for the worst thought grief taught me to think—what if he left because he wanted to?—because now I know he didn’t, and the part of me that doubted is a creature I hold with gentleness. I forgave the woman who thought candles could keep bad things away because now I know they can’t, but the world is kinder when it is lit. I forgave the city for being indifferent because that’s not a city’s job.

We ate dinner at our own table again. We learned how to do work and sleep and small jokes in a present tense that sometimes limped. We went to Maine and burned the chicken on purpose and laughed until we couldn’t breathe because the old rituals are still rituals even if you do them wrong. He put his hand over mine at crosswalks again. I stopped hearing his voice in strangers because now it lives where it belongs.

There’s a scar on his face I touch in the morning. I hate it and love it—hate what it took to put it there, love what it tells me when I need telling: he survived. We did. There’s a little white crescent on his wrist that makes me cry when I’m tired. Can openers will do that. I buy the pull-top cans now because I am allowed a superstition.

People asked us what we learned. I said nothing new. I said what I always believed: that love is the only argument you can win without raising your voice. That memory is water and stone. That justice is slow and sometimes, when the universe feels especially brave, real.

Part Two

Healing is a quiet work carried out with ordinary tools.

We stacked our marriage back together like books we had stored on the wrong shelf. This one is laughter. That one is “call me when you land.” This one is the soup he makes when I look like I haven’t eaten hope in a while. That one is the way I learned what trauma looks like on his face when a door slams too hard behind him and how to say, without spooking it, “It’s a door. It’s the wind. We’re here.”

His memory came back in mosaics. A smell (“You used to wear that perfume when we fought because you said it made you feel armored”). A song (“I sang the harmony on the bridge and you said I was a whole band”). One afternoon he remembered the exact shade of the paint in our bathroom and we stood under the awful lightbulb while he described “gray with thumbprints,” and I realized he was right, that our stupid, inadequate paint was perfect because it was ours.

We went back to our places like tourists on a pilgrimage. The bench by the river where he had told me that he wanted to make a life so quiet inside it sounded like a promise. The cheap Italian place in the South End where the waiter had comped our dessert when he heard my last name because his mother had been a Parker, too, and he believed in coincidence. The footbridge where he had proposed, which had been replaced by a nicer one, which is how life works sometimes and you either learn to see beauty in the upgrades or you mourn the rust forever.

What doesn’t get said about trauma often enough: it is boring. Not the what happened, though people love that, a story to pass around like a rare coin. The after is the dull work of “again.” Again to the neurology appointment. Again to the lawyer. Again to the closet to take down the sweater you put up there when you thought you would never have to see it again. Again to the argument you already had last week when he forgot to text because time is slippery for brains that have been hit and for hearts that have been broken.

We learned the art of the do-over. “Ask me that again as if we’re on the same team.” “Say that again without leaving the room first.” He learned to tell me when everything in him was about to go white noise. I learned to tell him when everything in me was about to go loud. We learned to agree on simple rules like never going to bed angry and always having tortillas in the freezer and saying “I am afraid” instead of “You are wrong.”

When I told Mrs. Henderson he was back, she cried into her tea and then made a brittle joke about pas de deux. She asked to see him and he sat at her small table and listened to her tell stories about 1963 as if the date were written in gold. When she died—because people do—she left us her music box that plays a tune so afield from our lives that it makes me laugh every time I wind it. It sits on our dresser and sometimes the sound makes me feel like grief might, in fact, be a dance after all and not always a wound.

There were people to forgive or not. Victoria’s lawyer sent a congratulations once the legal dust settled that made me snort coffee. Victoria herself didn’t send anything. She does not occupy my head as a villain or a saint, just as a person who built a house on shifting sand and then wept when it moved. There are parts of my life I cannot imagine without her—namely, the part where Daniel is back. This is what I mean by “mixed,” and why I wish English had a word that meant “I hold this contradiction without moving the furniture of my soul.”

The men who hurt him went to prison. I do not think about them except when the news is compelled to remind me they exist. The ex-wife’s family learned that money is not a god. The wealthy client sent a bottle of wine we couldn’t afford and a handwritten note that said “I am sorry” in a way that felt too late and somehow exactly on time.

There were bills, because the universe has a sense of humor. We paid them. There were headlines for a week. We read none of them. There were relatives who found our number and said “I always knew he didn’t leave on purpose,” and I did not ask them why they had not called in the years in between. There was our landlord, who gave me a hug and then slipped $200 into an envelope on our door anyway, the kind of small mercy that tells you the world is not entirely made of metal.

I have a folder in our kitchen drawer labeled PROOF. Inside it are the skeletal pieces of a story I never wanted to learn to tell—the dental records, the police reports, the investigative notes, copies of orders with seals like stickers on schoolwork. I don’t open it often. I have another folder labeled LIFE. It’s full of recipes torn from magazines (one we hate, marked with a skull), a list of books we want to read this year and haven’t, a childlike sketch of a house with a tree bigger than the roof because that’s how hope draws. We open that one a lot.

I will not pretend we returned to “before.” Before isn’t a place you can go back to once you have learned that the ground and the air can change places without warning. But there is an “after” that includes laughter that doesn’t feel stolen and naps on Sundays and the knowledge that the person in the next room will still be in the next room when you go get something from the kitchen and come back.

One afternoon, months into the rebuild, we walked down to the river. Autumn had gone thin and gray in that particular New England way where the city smells like smoke and school supplies. A little boy was feeding ducks with a grown man who I assume was his father because of the way he stood slightly behind the child as if he could catch the present with his hands if it slipped. Daniel watched them and his face went soft in a way I had not seen it go yet in this new life. He said, very simply, “I want that.”

“Bread?” I asked, because I have learned to go slow so I don’t trip over meanings.

“That,” he said, and his hand brushed mine and settled there. “Some future that has crumbs and ducks and no cameras.”

We have it, in so many small ways it would break my heart to list them, so I won’t. I will say instead that it exists in the way he learned how to take the bus out of his muscle memory—left hand on the rail, step-right—and how I learned to love the scar that means here is where the story bent and didn’t break.

On the day his name was restored on paper, a clerk at City Hall raised her eyes over the counter in that tiny, conspiratorial way government workers have when they have seen things. “Welcome back,” she whispered. We walked out into a city that had kept our seat and found it still warm. We bought coffee from a shop where nobody knew us anymore and drank it on a bench we had once claimed and the coffee was not as good as it had been, which is fine. Sometimes the coffee being worse is proof of life.

I have no moral except the obvious ones. Love is sturdier than people give it credit for. Money can invent paperwork but not truth. The human brain will heal if you give it time and stories and the exact smell of a parking garage on the day everything went sideways.

If you are reading this because you, too, stood in a kitchen with candles and a chicken and then learned what absence weighs, I won’t insult you with advice. I will say only this: your eyes are not lying to you. The ground is real even when it tilts. There is a woman with a folder labeled PROOF who sees you and a man with a scar who would tell you, if he could, that sometimes you choose each other again, and that counts.

In our apartment, above the little table where we once plotted budgets and vacations and reconciliation strategies with the universe, hangs a photograph from our wedding. Not the magazine-perfect shot—one that a tipsy cousin took, crooked and slightly out of focus. My veil is caught on a chair. Daniel has laughter in his mouth and not quite out yet. There are leaves in the corner like coins. We kept it over the mantle these last months on purpose because it tells the truth better than any staged thing: our life has always been, will always be, a little off-kilter, a little imperfect, brilliantly alive anyway.

Some evenings I wind Mrs. Henderson’s music box and let its fragile tune flutter around the room while Daniel reads and I try to decide whether to light a candle for no other reason than it makes the air feel like a decision. The music runs down and we do not. He looks up and catches me looking and we smile the resigned, grateful smile of people who know exactly how unlikely their present is.

He reaches for my hand.

I let the world end and begin again in that simple grip.

END!

News

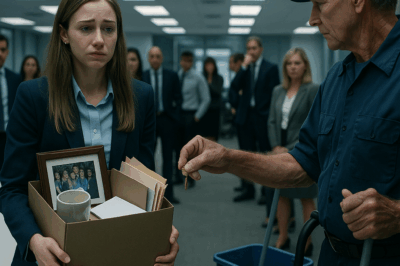

I was fired in front of the whole office. Then the janitor handed me a key and… ch2

I was fired in front of the whole office. Then the janitor handed me a key and… The rain started…

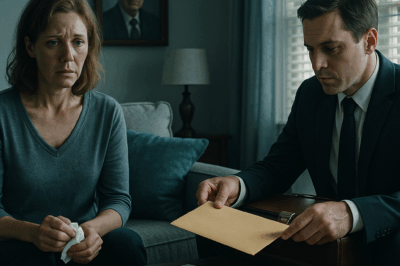

My 89-year-old father-in-law lived with us for 20 years without contributing to our expenses. After his d.eath, I was sh0cked when a lawyer arrived with explosive news. ch2

I got married at 30, with nothing to my name. My wife’s family wasn’t well off either; there was only…

I Said Goodbye to My Dying Husband and Walked Out of the Hospital—Then I Heard the Nurses Talking. ch2

I Said Goodbye to My Dying Husband and Walked Out of the Hospital—Then I Heard the Nurses Talking Part One…

At His Estate, I Was Just the Caretaker — Until I Realized Who Set Me Up to Fail… ch2

At His Estate, I Was Just the Caretaker — Until I Realized Who Set Me Up to Fail… Part…

After My Husband Died, I Tried to Sell His Garage—But Inside Was Something I Never Expected. ch2

After My Husband Died, I Tried to Sell His Garage—But Inside Was Something I Never Expected Part One The…

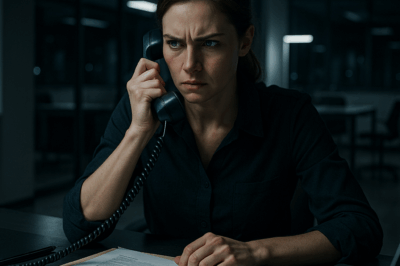

My Husband Snarled Over the Phone, “You’ll Crawl Back on Your Knees!” — But He Never Expected… ch2

My Husband Snarled Over the Phone, “You’ll Crawl Back on Your Knees!” — But He Never Expected… Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load