At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was…

Part One

I should have been excited. Thirty was supposed to feel like a threshold—one foot still in the noisy bloom of youth, the other stepping into a steadier light. Instead, dread settled over me like a heavy coat I couldn’t shrug off. The party my husband planned felt less like a celebration and more like a corporate launch with my name slapped on the banner. Somewhere between my twenties and this particular Tuesday, I had slipped from being a person to being a presentation.

“Don’t embarrass me, Natalie,” Richard had said three days earlier, the words soft as velvet and sharp as a paper cut. “Everyone will be there. Do not show up in one of your ridiculous skirts and sneakers.”

He said “ridiculous skirts and sneakers” the way some men say “poor manners.” He said “everyone” the way the men at his firm said “the markets,” with a reverence that did not include me.

I walked the mall that Saturday with a numb kind of determination, fingers trailing over silk that shimmered under the lights, past sequins that winked like lies. I’d always loved clothes you could breathe in, dresses that swished and laughed with you, cotton T-shirts soft from too many washes. But those weren’t what wives of partners wore to parades held in their honor. They wore sheaths that didn’t forgive and heels that said things about their husbands’ balance sheets. Richard had told me as much, over cocktails in other people’s houses, on the ride home from his firm’s holiday gala, in the silence when we got into bed and he turned away.

I was staring at a display of glittering gowns when a voice I knew better than my own reached for me. “Darling,” he said—warm in a way I hadn’t heard in years—and my heart leapt like a dog at a door.

I turned, smile already rising, and froze. He wasn’t alone.

She was a shimmer in red and gold: tall, blond, skin like poured cream, a blouse that clung as if it had been molded to her. Richard leaned in close to her ear, the corners of his mouth turned up in a way I had once thought belonged to me alone. His hand rested on her hip, a proprietary press, the touch of a man very sure of his stage.

They moved together toward the bridal boutique as if drawn by gravity. The window glittered with a field of white—lace like frost, satin like moonlight. I followed without deciding to, slipping in behind a rack of tuxedo jackets as the door chimed.

“Something elegant,” Richard told the saleswoman, the cadence of command in his voice. “I want the most beautiful gown you have.”

“For you?” the woman asked, polite disbelief crinkling her mascaraed eyes.

“For her,” he said, and the blonde—Amanda, I’d learn later—tucked a lock of hair behind her ear and laughed a laugh you could pour straight into a flute and serve to a room.

“When will you divorce that wife of yours?” she murmured, as if we were sharing a secret.

“Soon,” he answered, like a man discussing a minor merger. “As soon as I get her signature on the transfer papers. She’ll roll over if I press. She always does. Trust me.” He squeezed her hand. “We’ll have our wedding next month.”

The dresses around me tilted and swam. He wasn’t just unfaithful. He was erasing me, drawing up plans to bulldoze the house of my life and build a newer, shinier version over it. And if I wasn’t very careful, I realized, he’d use my hands to sign the permits.

I left the boutique on legs that didn’t feel like mine and drove to my daughter’s school by muscle memory. Katie’s little pink backpack hit her knees when she ran, her gait uneven but determined, sleeves askew, hair ribbons listing. She stumbled on the curb and then righted herself, cheeks flushed, eyes bright as coins.

“Mommy,” she sang, flinging herself at me.

She smelled like crayons and soap. I folded around her and breathed deep, letting her shrink the world back down to a size I could hold. “How was your day?”

“Matthew teased me again,” she said matter-of-factly, but her mouth trembled. “He said I walk funny. Everyone laughed.”

“You are perfect,” I told her, bending so my eyes were level with hers. “Strong and brave and perfectly you.” I meant it, fiercely, too fiercely, maybe, because that was where it always caught in me—at the reminder that some of the world, including her father, would have given anything to sand down the parts of her that weren’t convenient.

She was buckling herself into the booster when a man’s voice—warm, steady—came from behind me.

“Mrs. Whitaker?”

I turned. Tall. Broad shoulders. Suit I couldn’t afford. Little boy at his side whose cowlick did whatever it wanted.

“Daniel Hayes,” he said, offering a hand. “I wanted to apologize for my son. I heard what happened today. Matthew?”

The boy scuffed his sneaker against the curb, eyes somewhere near his shoes.

“Go on,” Daniel prompted gently. “Real apology.”

“I’m sorry,” Matthew mumbled. “I won’t say it again.”

Katie considered him with the regal seriousness of a small queen. “Okay,” she said finally. “But don’t be mean to anyone else, either.”

“Deal,” he said, and when his father smiled down at him, the boy’s shoulders loosened.

“She has spirit,” Daniel said to me as they started to go. “You should be proud.”

“I am.”

He hesitated, then said, “I’m a divorce attorney.” I braced instinctively—people do one of two things when they hear that: they flinch or they confess—but his voice held no prying. “I also have a friend—pediatric orthopedics in San Diego. If you’d ever want a consult. No pressure. He’s changed a lot of kids’ lives.”

Hope is a muscle that doesn’t choose when to flex. It jumped. “You’d share his contact?”

“Of course,” he said simply, as if a man offering you a road out weren’t the rarest kind of mercy.

The night of the party an army of caterers turned our house into a magazine spread—chairs dressed like debutantes, music that made people nod as if they understood it, oysters borne aloft like tiny chandeliers. Richard moved through the rooms like a man at the opening of his own museum. He’d banned Katie from the main floor with a clipped “She’ll trip, Natalie. The last thing I need is—” He didn’t finish the sentence. He didn’t have to. The contempt did the rest.

I’d intended to smile and nod and pour wine I wouldn’t drink. Then Amanda glided in, late and theatrical, crimson pooled around her feet, the air pulling around her as if even oxygen knew its place. A ring of whispers rippled through the room. She floated to us and said, “Still playing the good wife?” Lots of people heard that part.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Richard boomed four toasts later, hands raised for silence. “A special treat. My daughter will perform for you.”

I saw the nanny at the top of the stairs, Katie’s small fingers white on the banister, knees trembling. My blood went hot. “No,” I said, clear as glass. “She will not.”

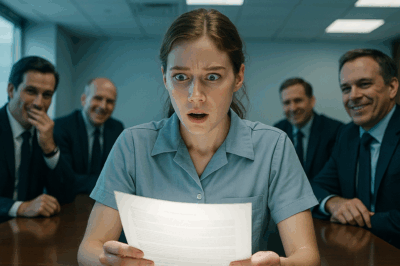

One hundred eyes swiveling. Richard’s smile did not falter; it got thinner. “Natalie, darling,” he said into the microphone like an MC kissing a viper, “someone has had a bit too much champagne.” He angled his phone, recording. Laughter rose like obedient applause.

If he wanted a scene, he got one. I took one step toward the stairs, looking up at our child. “You are not a trick pony,” I told her. “You are not a party favor. Go back to your room, sweetheart. We will come tuck you in.”

“Natalie,” he hissed when I turned back to him, but I was done listening. The room rustled uncomfortably. He lowered the mic and said under his breath, “You’ll lose everything.”

An hour later, after fake hugs and carefully placed outrage, the last guest left and the house exhaled. Richard poured whisky that smelled like money and said, “Tomorrow morning you’ll sign the company over. The house. It’ll go easier if you don’t fight.”

“You can’t take Katie,” I said, because shock makes you answer the wrong threat.

He smiled without his eyes. “I don’t want her. But a judge will believe she’s safer with me if I show them what you’re like. The breakdowns. The late nights. The video. I don’t need to keep her. I just need to scare you.” He swirled his drink. “Sign nicely, Natalie.”

At three a.m. I lay in the dark and realized there was no version of staying that did not end with me erased. Fear is a good alarm clock. Before dawn I was in his office, knees in my nightgown on the rug in front of the safe. He used the same four numbers for everything—his mother’s birthday, because of course he did. The lock turned with a soft, treacherous click. Cash. Documents. I took what we’d need to be human somewhere else: passports, birth certificates, account statements. I didn’t take the deed yet. There are some papers you fight for publicly.

I packed two bags, then unpacked one and repacked lighter. I tucked money into the hem of my coat and into the toe of a shoe and into the zipped inner pocket of Katie’s backpack. I made coffee. I woke her at six.

“Special day,” I said when she blinked up at me, and watched her run through the possible holidays we’d invented over the years—Pajama Pancake Sunday, Backyard Camping Night, Movie Marathon Monday—before deciding there must be a new one. She let me dress her in her school clothes. She let me braid her hair. She let me kiss her forehead twice. At drop-off I sent a photo to Richard. He grunted a reply: Meeting. Call later. Good.

Ten minutes after the bell, I was back in the office asking to sign my daughter out for a “doctor’s appointment.” I was halfway across the parking lot with Katie on my hip and a knot in my throat when a familiar car pulled in. Daniel unfolded from the driver’s seat, coat flung open, tie askew, concern drawing lines in his kind face.

“You look like you’re about to run,” he said, not accusing, not surprised, just stating the weather.

“I am,” I said, because sometimes honesty is the only thing that fuels your legs. “I need help.”

He opened the passenger door without another word. “Get in.”

The plane to San Diego was full of people who looked like ads for their own lives. I kept thinking someone would tap my shoulder and say, “Ma’am, you can’t take a child’s entire future as your carry-on,” but the flight attendant only touched Katie’s hair and said she liked her sneakers.

Daniel’s friend, Dr. Alvarez, had a smile that made me believe other people’s miracles. He made no promises. He drew pictures on the back of an intake form. He talked to Katie like she was a person, not a problem. “We can help a lot,” he said finally, and the ground steadied.

Surgery day: waiting room coffee I didn’t drink, hands that wouldn’t hold still, Daniel’s palm a warm weight between my shoulder blades. When Dr. Alvarez came out, mask pulled down, eyes creased with exhaustion and triumph, I cried without embarrassment. “It went well,” he said. “She will work hard, and it will be worth it.”

Therapy hurt. Katie swore at me once, a word she’d heard at the park from a teenager with no mother hovering. I told her I loved her anyway and then swore at the car door when I accidentally slammed my hand in it. We learned to keep going. At night Daniel drove us to the beach. We let the Pacific teach us the rhythm of breathing again—rush in, rush out, always return. The first time Katie walked six steps on sand, she put her hands in the air and laughed like a bell. I watched the horizon and thought, This is what beginning again looks like.

While I was learning to measure progress in inches and seconds, the Seattle version of my life fell apart without me in it. Word came in sideways. Amanda left when she realized weddings require more than gowns and declarations; they require a man with money and the willingness to keep it. Richard found out what happens when you build a house from paper. The board didn’t back him. Investors stopped answering. The lacquer on his charm cracked. The three voicemails he left me in a week went from furious to pleading to resigned. I saved none of them.

When Dr. Alvarez cleared us to fly home, Seattle was gray and unapologetic. The boardroom table felt different under my palms. Men who had practiced not seeing me tried to recalibrate. “Good to have you back,” one said, like I’d returned from a sabbatical instead of an exodus. I smiled the smile women learn when they want to win. “We have work to do,” I said and meant it. The juggernaut that had been ours became mine again, and I didn’t let it chew me up a second time.

Richard tried to take me apart in court, the way men like him play pretend gladiator: with spreadsheets and edited videos and words like “unstable” dressed in suits. He brought the clip from my birthday, the one where I raised a glass as if I’d once believed the world could be simple. Daniel rose slower than my panic and laid other pages on the table: the caterer’s affidavit, lab results, the full footage that showed a woman hosting, not unraveling. He took the judge through bank statements and business records and a timeline of a man hollowing out a marriage for parts. Richard’s lawyer had nothing left to do but object and object again, like a metronome trying to keep time no one else heard.

“The court grants full custody of the minor child to Mrs. Whitaker,” the judge said, and the gavel’s knock sounded like the first note of a new song.

Outside, the sky decided it might try blue. The courthouse steps felt like ground at last, not the edge of something. Richard sat inside one minute longer, looking smaller than money can compensate for. I did not look back.

We didn’t throw a party. We went for pancakes. Katie put whipped cream on her nose and Daniel pretended to be scandalized. He wiped the cream off with his thumb and put it on his own nose. She laughed so hard she hiccuped. My mother insisted on paying the bill, then cried anyway. When we walked out into the cold, I reached for Daniel’s hand, and he let me have it.

Not long after, I found myself at the park while Katie ran with a pack of kids, feet sure in a way that made my chest ache in the best possible way. Daniel stood beside me with two hot chocolates and said, “Sometimes I think the bravest thing we do is not leave,” and I nodded, because sometimes the bravest thing we do is exactly that: stay with ourselves.

The party dresses at the mall came down. The bridal boutique replaced its winter window with summer silk. I walked past once with Katie on my hip and felt nothing but air. The mannequin in the corner wore a gown with sleeves like wings. “Pretty,” Katie said.

“Very,” I said. “But not our kind of pretty.” We bought sneakers with glitter instead.

On a Saturday that smelled like wet grass, I found the courage to put away the last of the old life I’d been dragging. I opened the closet and ran my fingers over the emerald dress I’d worn to my own indictment. “You were beautiful in it,” my mother said from the doorway.

“I know,” I said. “I just wasn’t free.” We donated the dress. Someone else would wear it to a party where she wasn’t scenery.

In the evening, drama in the sky—clouds breaking, sun slicing through, people on porches making halfhearted jokes about finally, finally. Daniel and I sat on the back steps while Katie chalked galaxies on the driveway. “What will you do for your birthday this year?” he asked.

“Eat cake at home,” I said. “Invite people I love. Wear a ridiculous skirt and sneakers.”

He laughed, the sound warm and unstartled. “I’ll be there,” he said. “If that’s okay.”

“Good,” I said. “Bring candles.”

He did. We ate cake in the kitchen and got frosting on our faces, and I wore a skirt that swished and shoes that made no sense with it at all, and Katie blew out the candles with a wish she refused to tell, and my mother took a photo where we are all looking at the wrong thing and still somehow right. The picture is framed on my desk now. If you look closely, you can see through the window the faint outline of chalk planets on the driveway, and if you look closer still, you can imagine the noise of us, which is to say the proof that we exist as we are.

Betrayal has a specific gravity. You can drown in it. Or you can learn to float. In the mall that day, hidden among dresses meant for beginnings, I watched an ending announce itself and thought the world had finished with me. It hadn’t. It had just changed key. I will go on turning years like pages. I will go on buying sneakers and swishy skirts. I will go on mothering and making coffee and saying no when someone tries to make me small. And when I walk past a window glittering with white, I won’t think of erasures anymore. I’ll think of the day I ran, and the day I stayed, and the way the ocean taught me to breathe.

Part Two

San Diego expanded in my chest like a lung finally given air. We arrived with a wary bundle of courage and a girl who had learned to look at the world sideways because some parts of it tripped her, and we left with muscles made strong by work and a new way of measuring grace.

Katie learned the hard math of progress—inch by inch, one beep of the therapist’s metronome at a time. On good days she walked to the shore by herself and let waves lap her ankles, declaring herself Queen of All Salty Things. On bad days she cried and threw the elastic bands at the mirror and then cried because she’d cried and we ate grilled cheese on the floor and watched cartoons until the edges smoothed. The therapists called it “outcome variability.” Katie called it “my legs being dramatic.” I called it “bravery.”

Back in Seattle, I learned to put myself in rooms I used to walk passively through. The company my parents built had been shaped by Richard into something that functioned like a mirror—reflecting only what he wanted to see. In the months that followed the trial, I replaced finish with function. We rewrote policies with words like dignity and transparency instead of words like optics. I learned more about supply chain logistics than I’d known existed. I surprised myself by loving some of it. Power, when it is not being used to make you smaller, can be a generous tool.

Richard, I am told, joined a gym he didn’t go to and a men’s group that told him he was a victim of a changing world and a book club where he never read the book. Amanda married an orthodontist and moved to Scottsdale; her Instagram features a lot of teeth and sunsets. There is always a bench at the edge of ruin where people sit and try to sell each other reasons. I do not visit.

Katie started writing letters to Dr. Alvarez on paper she decorated with stickers of dolphins and planets. “Thank you for fixing my walking,” she wrote. “I am faster than my friend Lilly now. Please fix someone else next.” He wrote back every time. “I fix no one,” he wrote once, “I just help them fix themselves. Like you did.” She read that sentence ten times and then traced it on our kitchen whiteboard in her wobbly letters for a month.

Daniel and I learned to love without making it too precious. There were no speeches—just Tuesday night pasta and Friday morning coffee and his coat dropped over my shoulders when I’d forgotten mine. We took Katie to the aquarium and let her pretend she was a shark narrator with a very specific accent. We took my mother to a matinee, and she fell asleep, and he pretended to be outraged. We did not rush. Love that follows triage does its own pacing.

On a gray Sunday I took Katie to the mall because she wanted to see the holiday fountains dance to music and because one of the lessons I keep relearning is that new memories push out old ghosts. We passed the bridal boutique. The windows flamed with winter white. Katie pressed her nose to the glass. “Do all brides wear white?” she asked. “No,” I said. “Some wear red. Some wear blue. Some wear pants to make certain people nervous.” She laughed until she hiccuped, then insisted we go to the bookstore to pick out a gift for Daniel “because he reads very serious books and needs a funny one.” She chose a collection of New Yorker cartoons. He laughed at all the ones she didn’t get and explained none of them, which is the trick.

The case against the hospital ended in a settlement that paid for more therapy than we’d need and scholarships we insisted be named for the two nurses who’d worked springs on end without enough support until mistakes became inevitable. Diana cried in my kitchen when I told her. Natalie sent flowers and a note that said, “I still think of that night. I still light a candle.” We invited her to the park. She came. She sat on the bench and watched the boys argue about a foul, and it broke her open in what I hope was a healing way.

The first snow of the next winter fell in earnest, not the early dust we’d gotten before. Katie ran out in her boots and wanted to see how her new legs felt on ice. “Carefully,” I said, which is a word I say too often and am trying to learn to replace with “bravely.” She stepped onto the sidewalk like a queen testing a new kingdom. She slipped and then didn’t, arms flung out, cheeks pink with delight. “Again,” she demanded, and I stood behind her with my hands ready and let her.

When I turned thirty-one, we didn’t throw a party. We made pancakes in ridiculous shapes, and my mother wore a hat with candles on it that lit up when you tapped the brim, and Daniel brought flowers that came in a paper wrapped like a dress, and Katie sang a song she’d made up about being good at being old, which stung less than it would have a year ago. We toasted with orange juice. We danced in the kitchen to a playlist that included both Motown and Beyoncé and a song from Katie’s show about sea creatures.

There are days still when a flash of a red dress on a stranger makes me feel like I might fold. There are mornings I wake with the taste of old fear in my mouth. There are nights when the house is too quiet and I go stand in Katie’s doorway and listen to her breathe. There is grief that sits on my chest like a cat and refuses to be moved. But it purrs less. It allows me to stretch.

Sometimes after dinner Katie pulls a chair up to the counter and tells me she is going to make “learning soup,” which means she dumps dry pasta into a pot and asks me questions like, “If love is invisible, why can I feel it?” I tell her it’s like heat—no shape, but it changes everything it touches. She says, “Like the sun,” and I say, “Exactly,” and we dance around the kitchen with wooden spoons as microphones until we are out of breath.

If you stand in the right spot at the edge of the park and look west just as the sun slips, Seattle goes briefly transparent. You can see the city’s bones—the cranes, the cranes, always the cranes—and past them, wilder lines: mountains shouldering the sky like the backs of sleeping beasts. On a day like that, with Katie barreling back toward me and Daniel jogging slow behind her, my mother on the bench telling the person next to her the entire story of what we have survived with hand gestures, I can feel how the world rearranged itself and still held, how something that cracked right through the middle could become a mosaic.

The mall where I once hid in a bridal boutique watching my life tilt is still there. Occasionally I take the escalator up just to prove I can. In the window the mannequins wear gowns that would make me itch. I don’t stay long. I walk past and into the light, where my daughter walks with both arms spread, where a man waits with the good kind of patience, where my feet know the way home.

There is a story we are told about breaking: that it’s the end. It isn’t. It’s the invitation. On the day I followed my husband into a room full of white dresses, I thought the story of me had been stopped with a hand on its neck. Turns out, it had just been turned another direction. Turns out, there was a door. Turns out, the key was mine.

And this, at last, is the truth I will hand my daughter when she is old enough to ask me why the world wobbled once when she was small: I caught him. He planned to erase me. He couldn’t. We ran. We stayed. We chose again. We lived.

END!

News

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… CH2

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… …

“Mister, please take my little sister, she’s only six months old and very hungry.” Ethan turned and saw a 7-year-old boy holding a tiny baby close. ch2

The city’s pulse was a frantic drum against Ethan’s ribs. Time was a thief, and it was currently picking his pocket…

The Waitress Said, “My Mother Has the Same Ring.” — The Millionaire Looked at Her and Froze. ch2

Graham Thompson, the 53-year-old founder of Thompson Grand Hotels, sat alone at a corner window table in The Beacon, a warm, wood-paneled…

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… CH2

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… Part One…

My Son’s Family Left Me Stranded on the Highway — So I Sold Their House Without a Second Thought… ch2

Everything began about six months ago, when my son Ethan called me sobbing. “Mom, we’re in trouble,” he choked out,…

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract… CH2

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract……

End of content

No more pages to load