At the Hospital, My Parents Asked the Doctor, “Can We Swap Her Organ to Save My Son Instead?”

Part One

It started with the sound of metal tearing open like paper. Liam was driving, one hand on the wheel, the other flicking between playlists while he talked about a prestigious internship our mother had lined up for him. I remember thinking the sunlight on his cheek made him look younger, not everything our parents had loaded onto his shoulders. Then the truck drifted across the double line, the horn, the sudden, violent sideways jerk, and that awful crunch that feels like the end of the world and the beginning of something else.

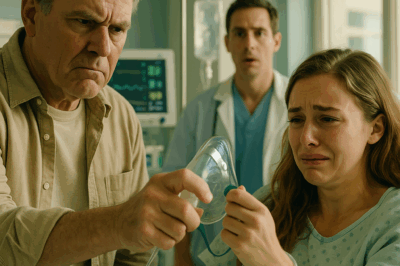

When I clawed my way back up into the light, the ceiling above me was a grid of fluorescent rectangles, and the air smelled like rubbing alcohol and plastic. IV lines webbed my arms; pain stitched across my abdomen like a crooked seam. I tried to call for Liam, but my throat ground against itself and only a sound I didn’t recognize came out.

A nurse in cornflower-blue scrubs leaned over me. “Easy,” she murmured, offering an ice chip. “You’re at County. You’re safe.”

My parents arrived not long after—but they didn’t look wrecked or wild with relief the way I’d imagined parents look when they find out their daughter survived something like that. They were composed, irritated, as if the traffic to get to the hospital had been the real imposition.

“She’s awake,” my mother told the doctor standing at my bedside, like she was checking an item off a list. She did not touch me. My father studied the wall behind my head as if it might provide a different story.

The surgeon—a compact man with crescent moons under his eyes—looked relieved. “You’ve been through major trauma,” he said, meeting my gaze. “You lost one kidney in the crash, but the other is functioning, and you’re stable. That’s what matters.”

I rasped around the ice and managed, “Liam?”

“He’s fine,” my mother said flatly. “Bruises, that’s all. You’ll be here a while.”

The sentence landed and slid across my skin like a cold hand. Liam was fine. I was not. My parents looked… inconvenienced. It didn’t make sense, so I set it aside like a puzzle piece I’d rotate later to see where it might fit.

Recovery was days stitched together by beeping monitors and the taste of saline. The nurses were kindness wearing comfortable shoes. The night-shift doctor called me “kiddo” and told me stories about his sons to make me laugh, which hurt, but in a good way. My parents visited as little as the situation allowed. Liam didn’t visit at all.

I figured it was shock or complicated grief until, on a night when pain and cold had braided together under my skin and refused to let me sleep, I heard voices drifting in from the hall. My parents. A doctor. Low, urgent.

“So you’re saying,” my mother’s voice, precise as tweezers, “if we take her remaining kidney—”

“She would die,” the doctor’s voice snapped, then pulled itself back into professionalism. “Your daughter lost her left kidney in the accident. Removing her right would be incompatible with life.”

“She’s seventeen,” my father said. “No real plans. She’s always been a… drifter. Liam has a future. He needs this.”

“She’ll never be able to lift much or run marathons,” my mother added, as if she were itemizing my defects on a ledger. “This would be a sacrifice that meant something.”

There was a silence so heavy I thought it might collapse the hallway. “You’re suggesting,” the doctor said, each word careful, “killing your daughter to harvest her organ for your son.”

“She’d be doing something good for once,” my mother replied.

I lay perfectly still, the sheets pulled up to my chin, and felt my world tilt. That was the first time I wondered if I’d been wrong about the story of my family. I’d always known Liam was the golden boy, the sun around which we orbited. I’d always known I was the spare. But I hadn’t known, not really, how far that sentence could stretch.

They left; their footsteps faded. I watched the squares in the ceiling. When the squares stopped spinning, I called for the nurse and asked, in the smallest voice I could manage without crying, to speak to the social worker.

Her name was Judith. She had the kind of patience that looks like it can absorb any heat you aim at it and still hold. She sat in the plastic chair by my bed while I told her, in halting pieces, what I’d heard. She didn’t write anything down until I finished. Then she clicked her pen, closed her notebook, and made a call from the hall.

By lunch, security had posted a guard at my door. By dinner, the hospital’s ethics committee had filed a formal report and the medical team had locked my chart so that no one without a direct need could access my information. By the next morning, a judge had granted temporary legal protection: no visitors without my consent; no medical decisions shaped by people who believed they owned me. Judith sat on my bed and said, “You deserve to live on your own terms,” like it was a prescription.

When my parents found out, they stormed the nurses’ station. I watched from my window as my mother pointed past the clerk’s head and hissed, “She belongs to us.” I watched security walk them out. I watched my father not look back.

“The kidney girl,” some of the staff started calling me in whispers, their faces tight with anger they didn’t quite know where to put. One resident squeezed my hand and said, “It takes a different kind of courage to say you want to live.”

It wasn’t bravery. It was instinct. Somewhere underneath all their stories about who I was, I had kept small, stubborn parts of myself in drawers no one knew about. Now, slowly, I took those out and held them up to the light.

I stayed in the hospital three more weeks. When they discharged me, it wasn’t to my purple bedroom with the posters on the ceiling; it was to a spare bed in a county apartment with thrift-store furniture and a foster mother who smelled like cinnamon and wore her reading glasses on the top of her head. Safe isn’t always soft. But safe was everything.

I finished high school online in a haze of algebra and physical therapy. I worked nights at a bookstore, recommended novels to strangers, and stacked paperbacks with covers that looked like home. I kept every receipt. I learned the first language worth being fluent in: No.

Judith helped me file for a legal name change when I turned eighteen. I didn’t pick something romantic or daring. I picked my great-grandmother’s maiden name because it felt like stepping back onto solid ground after crossing a shaky bridge. I signed forms with a new signature that felt steadier under my hand. Harper Henderson shrank into the version of me that had tried to be good enough to be loved. Clare Olen learned to take up exactly the space she needed and no more.

Years passed. Quietly. While their story ran on somewhere else, I was busy building one in which I was both main character and author. I took an entry-level job at a healthcare startup not because I loved tech but because I knew what a waiting room feels like at three in the morning and I wanted to help design something better. I worked too hard in a way that would have made my mother proud if she’d known, except it wasn’t her pride I was working for. I grew out of an assistant’s desk and into a manager’s office. I learned to argue meetings into shape. By twenty-four, my name was on the door under the letters COO.

One Tuesday in late spring, my recruiter slid a new resume across my desk. “Good school,” she said, tapping the page. “Thin experience. Great interview skills on the phone.”

The name at the top yanked the air out of the room. Liam.

My coffee cooled in my hand. He had applied under his given name, of course—no reason not to when you assume the path ahead of you is one long red carpet. He had no idea that the girl he thought he could carve up and leave behind had chosen a new name, built a new life, and now sat between him and what he wanted.

I invited him for an in-person interview.

He walked into the boardroom with the same unthinking confidence he’d had at sixteen when he ran a yellow light at midnight and laughed about the way rules were for other people. He wore a suit that fit. His hair was shorter. His face did something complicated when his eyes met mine, a flicker between shock and relief and something that might have been fear if fear had ever thought it might be welcome in him.

“You,” he said. His voice cracked. “You’re… alive.”

“Alive,” I said, standing. My hand was steady when I offered it. “Healthy. Not yours.”

He stared at the glass wall where my name sat frosted in white. He looked at the plaques across from the window. He looked back at me.

“You’re the COO,” he said, as if saying it would make it less true.

“Yes,” I said. “Of the company you’re trying to join. The one that builds software to put patients in control of their own decisions.”

He dropped his gaze to his resume when I flicked a page. “Your grades are decent,” I said. “Your experience is thin. Your references are all people with my parents’ area codes.”

He swallowed. “Look, I—things haven’t been… I just thought… I didn’t know.”

“You didn’t know I survived?” I asked. “Or that I might grow into someone you couldn’t erase?”

He lifted his hands. “Whatever Mom and Dad said to you—I wasn’t part of—”

“They asked to cut me open and give you what I had left without asking me,” I said. The words didn’t shake. They sounded like I was reading from a report. “They weighed my life against yours on a scale they’d built and found me lacking. You were part of that the way you were part of everything. It was the air we breathed.”

His face reddened. “You’re ruining my life,” he said softly, maybe to convince himself, maybe because he’d never been in a room where he wasn’t the center.

“Do you hear yourself?” I asked. “The girl you were willing to gut is refusing to give you a job. That’s your definition of ruin.”

“What do you want me to say?” he blurted. “That I’m sorry? That I didn’t know how to stand up to them? I need this.”

“I want you to listen,” I said. “I want you to carry the sentence you say without thinking—‘I need this’—and ask yourself why it has always had to be someone else who pays for that need.”

The room was quiet in the way rooms are when they’re waiting for a judge. I let the silence do some of the work.

“I created a policy here,” I said finally. “It’s simple. We don’t hire anyone who has a credible history of exploiting, abusing, or financially coercing family or partners.”

“How would you know that?” he asked, almost sneering, because he couldn’t help himself.

“Because we ask,” I said. “Because we believe people who have never been believed. Because we look.”

I stood. The interview was over. “We will not be extending an offer,” I said. “And I’ll be sending your materials to our partner network so they can make informed decisions, too.”

“You can’t do that—” he started, and then he remembered that I could.

He left without looking back, because some habits you keep even when keeping them makes you small. I waited until the door closed and called HR. “One more note,” I said. “The blacklist.”

That night, I sat on my balcony and watched the lake turn from pewter to ink. My inbox pinged. A note from County Hospital: We’re instituting a new ethical protocol to safeguard minors’ consent in organ discussions. It’s modeled on the case you lived and the testimony you gave to the Board last month. We’d like to name it the Clare Protocol, with your permission.

Clare. My name. Not the one I’d been born into. The one I had chosen when I refused to let them write the end of me.

In the mail the next week: a letter without a return address but with my mother’s handwriting startlingly restrained on the front. Inside, the kind of apology that isn’t one. We’re ruined, it said. Liam can’t find work. We’re losing the house. You’re our daughter. Help us.

I wrote back on a sheet of plain paper with no letterhead. I was your daughter in a hospital bed when you tried to decide if my life counted. You chose your son. Now you live with your choice.

I sealed it and sent it and made tea and went to bed. Sometimes closure is loud. Sometimes it is a stamp sliding across an envelope and the way the air tastes when you open a window after a storm.

I didn’t hear from them again.

But the echo of that sentence in the hallway stayed with me in a way that no longer made my hands shake. Can we swap her organ to save our son instead? I turned it over like a stone and looked at what grows in the shadow of a thing like that. There was anger, yes. But there was also, unexpectedly, purpose. I had survived. Not just the crash, not just the insult. The story.

And I was the one telling it now.

Part Two

The nice thing about distance is that it gives you perspective you can trust. The hard thing is that it gives you perspective you can’t unsee.

After Liam’s non-interview, I kept waiting for the old anxiety to return—like a reflex you can’t train out. It didn’t. The place where my parents’ power used to sit inside me was now empty in a way that made me breathe more easily.

I turned my attention to the work that pays the rent and feeds the part of me that keeps little lists on sticky notes. Operations is just a fancy word for making sure everything runs the way it should, and after the mess I grew out of, there’s nothing more satisfying than a system doing what it promises.

We built a product that put medical decision-making back in the hands of the person whose body it was. It started as an appointment scheduler that treated people like people instead of numbers. Then it grew teeth: permissions you could lock with your thumbprint; alerts if someone tried to access your chart; a record of who had asked to see what. We presented to the Board for a countywide rollout, and I sat there in a blazer the color of a midnight river and talked about consent with a steady voice.

When the vote passed unanimously, the County Counsel asked if I’d like to speak at the press conference. “No,” I said. “Let the Pediatric Chair do it. I’ll be in the back making sure the audiovisual equipment doesn’t die.” It’s a version of power my mother wouldn’t recognize, and I like it better.

The news found the story anyway. A journalist showed up at my office with too-bright eyes and a voice that tried to make me say my old name. “You’re that girl,” she said, the way people say you’re that actress when they see someone on the street. “I’m someone else now,” I said. The article ran without a photo. Progress looks like a very careful paragraph and an editor willing to push back on a headline that makes trauma into clickbait.

When the County Board of Supervisors listened to testimony on a proposed ordinance that would codify minors’ rights to absolute consent in non-emergency organ donation, I wore flats and slacks and read aloud, quietly, about a night in an ICU when I lay in a bed and heard my parents ask to trade my life like it was a currency they had access to. A mother with a teenage daughter sat behind me and cried into a scarf. A father who looked like he could bench-press a car put his hand on my shoulder when I was done and said, “Thank you for making them hear it.”

The measure passed. We named the county policy for the anonymous case that had started it. The hospital named their internal protocol after me. I still can’t say the phrase Clare Protocol without laughing a little into my coffee, because I know how names work when you’re someone else’s daughter, and I like the way this one works now when I am my own person.

There were still practical things to attend to. My foster mother had two teenage girls pass through her house in one season who scared me even as they made me proud. I taught one to make rice without burning it. The other taught me how to do eyeliner in a way that didn’t make me look permanently startled. We ate spaghetti around a table too small for all our elbows. We traded phone numbers like talismans. We learned the names of each other’s ghosts.

Around the time the second girl moved on to a dorm two counties away, I received an email from a public defender who wanted to talk about a case that looked too much like mine. I met the client in a room that smelled like coffee and despair. She was thirteen. She told me her story without looking up. I asked her if she wanted a different name to tell it under. She said yes. We picked one together that made her smile. The motion to protect her consent was granted in fifteen minutes. It felt like holding open a door someone had wedged shut for too long.

At work, I became the annoying executive who insisted that people with lived experience sit at the table when we made decisions about them. It slowed us down. It made us better. My CEO rolled his eyes and called me a bulldozer and bought me a toy dump truck for my birthday which now lives on my desk under the plant I cannot keep from leaning toward the window. When we hired a new head of product, she asked in her interview if there would be room for motherhood. I asked her, “Do you want it? Tell me how it would fit into the life you want to build, and we’ll figure out where the edges go.” She did. We hired her. It’s a small thing to do differently. It changes everything.

Every once in a while, the past still write letters. Not from my parents—they understood, finally, that silence is the only response worth sending. But from people who had known the old me and wanted to tell me they were sorry. From teachers who wished they had paid closer attention. From a nurse who had stood outside my door the night my parents tried to trade me and had gone home and held her baby and cried because she hadn’t been able to protect every person she wanted to. I wrote back like gratitude. I do not want to be the person who stays angry forever. Anger was the instrument I needed. It’s not the one I want to play now.

And then there was the letter from Liam.

It came via email, which I hadn’t blocked because I thought it would be an interesting experiment to see if ignoring a name could make it smaller. I’m sorry, it said. Mom and Dad raised me to think the world was mine and everyone else was staff. That’s not an excuse. It’s a diagnosis. I don’t know how to make this right. I just didn’t want to be the person who never said he was wrong.

I stared at it for a long time. Then I wrote back: You saying it doesn’t change what was done. It’s not up to me to forgive you. Live differently. Change a tire for someone without telling the story about it later. Take some kid in your care to the library instead of to his fourth baseball practice. Teach consent like it matters. Ask for less than you think you need, and give away more than you think you have. That’s what making it right would look like.

He wrote back: Thank you. I didn’t expect a response.

I wrote: Me either.

That spring, the hospital’s foundation asked if I would speak at a fundraiser. I stood behind a podium under a chandelier and told a room full of people in rented tuxedos that the check they were writing would not make them good. The volunteer hours would. The way they treated the receptionist in the morning when their MRI ran late would. I watched an older woman put her hand on her husband’s arm like a promise.

After the speech, a man with a familiar jawline waited awkwardly by the hors d’oeuvres.

“Dad,” I said.

He flinched at the word. “Clare,” he said, and dropped his gaze to my shoes. “You look… like yourself.”

“I do,” I said. The sentence had multiple meanings. He looked thinner; grief had carved him in unkind ways. The edge of me that still bristled at empty apologies waited but didn’t thrum like it used to.

“Your mother…” he began, then let it go. “I was weak,” he said instead. “It doesn’t matter, I know. But I was worse than you remember me. I could have said no. I didn’t.”

“You could have,” I agreed. The chandelier chimed quietly because a door had opened somewhere. “And you didn’t.”

He nodded. “I’m… trying to be better now. It’s late. I know that, too.”

“Late is still something,” I said, not because he deserved it—maybe he didn’t—but because I want to live in a world where someone does not have to be good yesterday to try to be good from today onward.

He looked at me then in a way he never had, as if seeing me were a skill he was practicing. “Clare,” he said again, and I believed he meant it this time.

We did not hug. We did not take a photo. We stood in the glow of a room that had always belonged more to people like my parents than to people like me and made it ours for a minute. He left. I exhaled and realized I had been holding that breath longer than was good for anyone.

On the one-year anniversary of the Clare Protocol, County held a ceremony where the pediatric ICU staff wrote down on little cards one thing they had done to protect a minor’s choice and hung them on a string in the hallway. I stood with a cup of terrible coffee and read them all. Stopped a grandmother from seeing a chart she thought she had a right to. Pulled a resident aside and explained consent like he was five. Asked an angry father to leave and sat on the floor with his kid while she picked out a nail polish. It looked like a line of laundry. It felt like a prayer.

Emily sent another text one summer night when the sky felt like it wanted to be kinder than it had been all day. We need to talk. I wrote back, All the talking has been done. She replied, You’re cruel. I put my phone down and watered the plant on my windowsill and thought about the way the world divides itself sometimes into people who believe in wounds as identity and people who believe in scars as story. I cannot be responsible for which one my sister wants to be.

In the fall, I took a weekend and drove to the coast by myself. I stayed in a shabby rental with a view of a lighthouse that looked like it might topple any day and never does. I walked until the wind made me grin and then I sat at a chipped table and wrote a thank you letter to Judith, who had retired to a little town with a good farmer’s market. Your voice saved me, I wrote, because it was the first voice I heard in that building that said I deserved to live without adding ‘if’ or ‘but’ or ‘for.’

She wrote back: You saved yourself. I was lucky to be there to witness it. She included a recipe for zucchini muffins. I made them on a Sunday and underbaked the first batch and sent her an email titled Zucchini as Metaphor and she sent back a string of smiley faces like this one 💚.

Sometimes I still wake up at 3:17 a.m.—the time the monitors used to beep louder when the night was at its thinnest—and remember the exact sound of my mother’s voice in that hallway. I don’t shove it away anymore. I invite it in and let it sit for a second on the edge of the bed and then I send it into the kitchen to wash up the mugs so I can go back to sleep.

I think a lot about that day in the boardroom when Liam sat across from me and called what I was doing ruining his life. It felt nice to say out loud that he and our parents had wanted to take mine. It felt nice to say no. But that’s not the part I keep. The part I keep is the way his eyes changed the tiniest bit when I suggested a life where need could be hollowed out and filled with something like purpose. Maybe he will do it. Maybe he won’t. It’s not my story to write.

What is mine is this: a kitchen with three chipped plates and two good knives; a job where I get to say let’s ask the people this will affect more often than not; a legacy that looks like little cards clipped to a string in a hallway; a protocol named after the person I decided to be. A plant that reaches for the window and keeps growing no matter how many times I forget to turn it.

And every now and then, a letter from someone whose hospital hallway sounded like mine, who says, I heard what they said. I know what I deserve.

I write back with the ease of someone who practiced for a long time: Yes.

END!

News

At the Hospital, When I Needed Surgery, Dad Took My Oxygen Mask Off —Save It for Someone Who Matters. CH2

At the Hospital, When I Needed Surgery, Dad Took My Oxygen Mask Off — “Save It for Someone Who Matters”…

On My 25th Birthday My Parents Blindfolded Me for a “Surprise”Then Dumped Me Outside a Dog Shelter. CH2

On My 25th Birthday My Parents Blindfolded Me for a “Surprise” Then Dumped Me Outside a Dog Shelter Part One…

“Before My Marathon Race, Dad Smashed My Ankle With the Baton — ‘Your Legs Were Never Made to Win. CH2

“Before My Marathon Race, Dad Smashed My Ankle With the Baton — ‘Your Legs Were Never Made to Win” Part…

My Sister Gave My Child Expired Food While Her Dog Got Steak — My Parents Laughed “It’s just Expired. CH2

My Sister Gave My Child Expired Food While Her Dog Got Steak — My Parents Laughed “It’s just Expired” Part…

After I Lost My Baby Mom Laughed Finally One Less Useless Mistake Breathing Out Air. Dad Laughed. CH2

My Parents Laughed When I Lost My Baby—“Finally One Less Useless Mistake Breathing Our Air.” Dad Laughed. Part One The…

My DIL: “Oh please, your pennies mean nothing!” “This party is not for you!” CH2

My DIL: “Oh please, your pennies mean nothing!” “This party is not for you!” Part One It should have…

End of content

No more pages to load