At The Family Party, My Sister Slapped Me For Dressing Better Than Her In Front Of Everyone. So I…

Part One

My name is Arya Walsh, and I’m twenty-three years old. Last month, I walked into a fancy Italian restaurant in suburban Boston for my dad’s birthday dinner wearing a red dress that clung to the little confidence I had. I’d spent weeks saving for it—one careful shift at a time at the bookstore—hoping to feel beautiful for once, just to try on the possibility that I could be the main character in my own life.

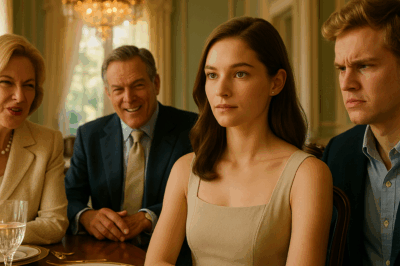

The private room was all white linen and soft chandelier light, the air warm with garlic and butter and the laughter of family friends who had known me since I was a kid. Heads turned. Compliments floated. I felt my shoulders ease back, my chin lift. Then my sister—Scarlet—saw me.

“Nice dress,” she sneered, just loud enough for the room to hear. I recognized the tone; I’d grown up inside it. Before I could reply, her hand cracked across my face, a hard, stinging slap that ricocheted through the clink of glassware and froze every fork in midair. The room went silent. My cheek burned. My mother, seated across from me, didn’t flinch. She let out a low, cold laugh and said, “You deserved it.”

That laugh was a match in a dry field. I stood there with the sting blooming, humiliation curling hot behind my eyes, and I felt something I’d never let myself feel in front of them: the clean edge of rage. That slap wasn’t just a strike; it was years of being told to shrink—condensed into one humiliating sound. I didn’t scream, I didn’t run. I sat down, swallowed the metallic taste in my mouth, and made a decision that hummed through me like voltage: I would not stay silent anymore.

Alone in my tiny apartment that night, the sting on my cheek gave way to a deeper ache. It wasn’t the pain—it was the pattern. Our childhood house in suburban Boston had always been a stage, and Scarlet, four years older and louder than the room, had always been the lead. Mom—Beatrice—called her “a natural star.” She praised Scarlet’s looks, her charm, her reckless spark. I was the quiet one, the afterthought, the grip behind the scenes. By twelve, I understood the choreography: I shrank, she shone, and Mom applauded. When Scarlet turned sixteen, she got the car keys. When I needed textbooks, I got a lecture about practicality.

Dad—Samuel—was a ghost with a set of blueprints. He loved us, I think, but his love was quiet to the point of disappearing. He’d come home late from his contracting jobs, kiss the air near my hairline, and retreat to his office. “Work hard, Arya,” he’d say, as if I wasn’t already stacking shelves at the bookstore after school to pay for the kind of future that didn’t involve waiting for the family spotlight to tilt my way.

Once, at fourteen, I won a writing contest. Mom barely glanced at the certificate before asking Scarlet about cheer tryouts. Another time, at Christmas, I saved for a wool scarf I thought Mom would love. She thanked me, then gushed over Scarlet’s last-minute earrings as if they were diamonds. Scarlet borrowed money and forgot it was borrowed; Mom called it “helping family” and told me to be generous. Generosity became a one-way current that flowed through me.

College didn’t loosen the knot. I moved out and learned the shape of a life I could afford: a mattress on the floor, a secondhand table, the bookstore job that paid my rent and tuition one paperback at a time. But the calls kept coming. Mom pushed me to cover Scarlet’s overdrafts, her phone bill, a sudden car repair. “She’s going through a rough patch,” Mom said so often that it lost its meaning. I said no more often than yes, but the guilt was its own bill.

The week before Dad’s birthday dinner, Mom called about a $3,000 credit card balance Scarlet had racked up. “It’s just a loan,” she clipped, as if the word could change the math. “You’ll get it back.” I didn’t have it. Even if I had, I was done rinsing and repeating the same lesson. I told her no. She sighed the sigh I grew up inside—disappointed, theatrical—and hung up.

That’s the day I pulled the red dress from the back of my closet. It was the brightest thing I owned, a fitted slip of courage I’d bought on a whim because I wanted to see what it felt like. I tried it on and stood very still in the mirror. For the first time in a long time, I saw someone who wasn’t apologizing for existing. I texted my best friend Lily a photo. She works in social media and knows what makes people look twice.

“You’re going to stop traffic,” she wrote back immediately. “Count me in for the dinner. I’ll be your hype woman.” I invited Jen and Matt from school too—good people who never treated me like a prop. I needed a buffer, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. Courage is easier in company.

Mom called again two days later to press about the bill. I refused again, my voice steadying as I said the word no. The silence after she hung up felt heavier than all her lectures. The next morning, Lily slid a coffee across the café table and asked if I was backing down. I shook my head and said the sentence that made my stomach flip to hear out loud: “Scarlet’s going to lose it.” Lily didn’t blink. “Let her,” she said. “You deserve to shine.”

The day of the dinner, I zipped the dress all the way up and stood in my doorway breathing like an athlete about to run a race. The restaurant glowed. The long table stretched under white linen like a runway. Dad sat at the head, smiling a small smile he might have saved for me. People who hadn’t looked at me twice in years told me I looked beautiful. For a moment, my skin felt like it fit.

Scarlet’s voice cut through the room: “Wow. Trying to steal the spotlight, huh?” She said it with a smirk that wanted a witness. I focused on Dad opening a tie from a cousin, anyone’s eyes but hers. She leaned across the table, wine glass tipping dangerously, and hissed, “Desperate dress. Trying too hard?” A few guests set their forks down. I said, “Thanks for the opinion,” and smiled the way you do at a stranger on the train who steps too close.

Then Mrs. Thompson, our neighbor who always slipped me extra brownies at bake sales, leaned over and said, “Arya, you look absolutely stunning in that red.” Other voices chimed—cousins, friends—compliments stacking like bricks I could stand on. Scarlet’s jaw tightened. She slammed her glass—sharp, small thunder—and before my brain could catch up, her hand came up and cracked across my face.

Time hiccupped. The room exhaled in a crown of gasps. My vision blurred—not from the pain, but from the way every stare pressed me flat. Mom laughed. “You had it coming,” she said, and in that second it felt like I had been slapped twice.

I saw Lily across the room, phone halfway raised, her face carved in disbelief. Jen and Matt froze, their own phones bright with accidental witness. A small, clear thought walked into my mind and sat down: these are not just pictures. They are my proof. Not just of the slap, but of the years behind it—of the favoritism I’d been told was love, of the silence I’d been taught was maturity, of the way my life had been a scaffolding for my sister’s spotlight.

After the cake and the strained toasts and the careful goodbyes, Lily and I sat on my couch and scrolled the photos. Scarlet’s hand mid-swing. My shock. Mom’s smirk in the background like a signature. Lily’s voice steadied. “We’re not letting this go,” she said. My hands trembled with adrenaline, but my shame had burned away and left something cleaner. I opened my laptop.

Lily and I workshopped a hashtag—something sticky and bright like the dress. We chose #RedAlert. I uploaded the clearest photo and wrote:

This is what happens when you dare to stand out. My sister slapped me at my dad’s birthday dinner because I wore a red dress. My mother laughed and said I deserved it. This wasn’t a one-off. It’s years of favoritism and control. I won’t stay silent anymore.

I told the rest: the loans that weren’t loans, the bills I’d paid to keep the peace, the way Mom’s love had always been a spotlight she could swivel. I named names—Scarlet and Beatrice—because euphemism is a kind of erasure. Lily posted the same to her larger following and tagged me.

By midnight, #RedAlert was trending in Boston. My phone buzzed like a hive. Friends, coworkers, strangers—people I’d never meet—poured their stories into my comments: sisters who bullied, parents who picked favorites, families that taught one child to bend until they snapped. “Don’t let them silence you,” one woman wrote. “Your mom’s laugh is chilling,” wrote another. A local blogger screenshot my post and titled it “Family Betrayal in a Private Dining Room.” In the morning, a small news outlet emailed asking for an interview.

Lily and I wrote a second post with receipts: times Scarlet had “borrowed” money and never repaid it, screenshots of texts from Mom insisting I “help your sister,” the Christmas when my gift barely registered while Scarlet’s was praised like treasure. It wasn’t revenge; it was a record. The news piece didn’t print my family’s names, but the community could do the math.

A local women’s group reached out, offering support and asking if I’d attend a meeting. I wasn’t ready to speak, but I said I’d come. We added a third post, a full-length shot of the red dress, the caption simple: This dress didn’t deserve a slap. Neither did I. The hashtag bloomed beyond our town, beyond Boston. I felt exposed and held at once, like standing on a stage and realizing the audience is on your side.

Three days later, my doorbell rang and the air changed. Mom. Dad. Scarlet. And Aunt Josephine, Dad’s older sister, who lives a few blocks away and has a way of walking into a room like she belongs there. They filled my doorway in a block of anger and unease.

“Take down the posts,” Mom said without hello, voice iced over. “You’re humiliating our family.”

Scarlet crossed her arms in my hallway like she owned the lease. Dad hovered behind them, tired and careful. Josephine lingered near the door, lips a thin line.

“I’m not taking them down,” I said. “You humiliated yourselves.”

“Drama queen,” Scarlet spat. “Posting to play the victim. Pathetic.”

For a second, my old training twitched—I almost apologized just to make the noise stop. Then I remembered my own cheek.

Mom pointed a finger. “This is childish. You’re tearing us apart over a dress.”

I laughed, short and sharp. “It’s not about the dress, Mom. It’s about you letting Scarlet treat me like garbage my whole life.” I looked at Dad. “And you saying nothing.”

He lifted both hands, peacekeeper’s palms. “Let’s just talk this out.”

“I begged you to talk for years,” I said. “You were busy.”

Aunt Josephine cleared her throat, eyes fixed on Mom. “Enough,” she said. “Arya isn’t wrong.”

“Excuse me?” Mom snapped.

Josephine’s voice didn’t shake. “Scarlet has been lying for years, and you’ve covered for her. When she was twenty, she stole $5,000 from my account. I confronted her. You begged me not to tell Samuel, said she was struggling and needed help.”

The room tilted. Scarlet’s smirk died. Mom’s eyes flashed, then shuttered. She didn’t deny it. “That’s not your business to share,” she told Josephine, and I realized how deep the rot went.

I turned to Scarlet. “You stole from Aunt Josephine?”

“It was forever ago,” she muttered, staring at a spot on my floor.

“It wasn’t just me,” Josephine said quietly. “She’s drained all of us. And Beatrice made sure no one said a word.”

Something straightened inside me like a spine finally aligning. “You knew,” I said to Mom, “and you still told me to pay her debts.”

“She’s your sister,” Mom said. “Family sticks together.”

“Family doesn’t slap family,” I said. “Family doesn’t steal.”

Josephine’s hand found my shoulder. “I should have spoken up sooner,” she said. “I’m sorry.”

I felt very calm. “I’m done,” I said, looking at Mom and Scarlet. “No more money. No more contact. No more pretending.”

“You’ll regret this,” Mom warned.

“The only thing I regret is not doing it sooner,” I said, and opened the door wider. They left in a tumble of outrage. Josephine paused, squeezed my hand, and followed them out.

That afternoon I filed a police report for assault with the photos and witness statements from people who’d messaged me privately after the dinner. My hands were steady as I signed. It wasn’t about revenge. It was about telling the truth in a language the family couldn’t rewrite.

A week later, my lawyer called: the court had reviewed the evidence and issued its verdict. Scarlet was found guilty of misdemeanor assault. The judge sentenced her to one hundred hours of community service and granted a two-year restraining order. My shoulders dropped an inch I hadn’t known they were holding.

The internet did what it does. #RedAlert had moved beyond my circle and the story found more oxygen. A local paper ran a follow-up on “toxic favoritism.” Neighbors stopped inviting Mom to book club. Mrs. Thompson—sweet Mrs. Thompson—crossed the street to avoid her. Mom posted a vague apology about “family misunderstandings,” and the comments reminded her what she had laughed at. I didn’t engage. Not everything is mine to fix, especially not other people’s consequences.

Dad left a voicemail. He wanted “to move forward.” With who? I wondered. The daughter he hadn’t defended? The one he defended by doing nothing? I didn’t call back. Silence, I was learning, can be a boundary too.

Aunt Josephine emailed to apologize again and to say she’d told the truth to other relatives. “I thought I was protecting the family by keeping quiet,” she wrote. “I see now I was just protecting the problem.” I wrote back: thank you for speaking when it mattered.

With Mom and Scarlet out of my immediate life, air moved differently through my apartment. I worked extra shifts, saved for a better place, bought bright curtains with Lily at the thrift store, and hammered nails into plaster without asking who else needed the wall. I started therapy and learned what happens when you stop tethering your worth to people who need you to be small. If grief is love with nowhere to go, then freedom is grief that found a home.

The women’s group invited me to a meeting—not to speak, but to sit and listen. I listened to stories that were mine and not mine: women who left houses full of shouting, women who survived the kind of love that bruises invisible, women whose mothers taught them to applaud their sisters while starving themselves. After the meeting, a woman named Sarah touched my arm. “Your post helped me leave,” she said. I swallowed hard and said thank you. When they asked for volunteers, I raised my hand and wrote my name next to “chairs,” “flyers,” “coffee.” I wanted to be the person who sets up the room where other women tell the truth.

And I kept the red dress. I hung it where I could see it when I reached for my coat, a small flag I planted in my own life.

Part Two

The consequences didn’t end at the courthouse steps. They rippled.

Mom—Beatrice—took the hit the hardest socially. The posts painted her as the mother who laughed at her daughter’s pain, and the small town we grew up in runs on a current of reputation. Church ladies whispered, book clubs went quiet when she entered, neighbors looked at their shoes. She tried to pivot, to post soft-focus photos about forgiveness and family, but the comments didn’t let her narrate over the facts. “Accountability is love,” one woman wrote beneath her apology. “Start there.”

Dad remained a quiet planet orbiting whatever hurt least. He called once more and said he wanted to “heal.” In therapy I’d learned that apologies and amends are cousins, not twins. I texted him that I needed time, and by “time” I meant actions. He sent a thumbs-up, a punctuation mark with no hands attached.

Scarlet didn’t appeal the verdict. The restraining order drew a clean line she hadn’t expected to meet. Friends told me she’d started community service at a food pantry and that the volunteers there liked her when she wasn’t performing. I tried to let that soften me and felt only the empty space where the slap had been living in my jaw.

At the bookstore, I moved from cashier to events coordinator, which mostly meant I got to string fairy lights and decide which author got the big chalkboard. I poured my energy into calendars and chairs and cozy corners where stories bloom, and it felt like building something good. Lily came by after work and tried to teach me the difference between reels that perform and reels that are just pretty. “They’re not mutually exclusive,” she said, and I wished that had been true in my family.

I rented a slightly bigger apartment with a secondhand sofa that didn’t sag, and Lily brought over a spider plant that started thriving in my window like it owed me an apology. On Sundays I cooked simple things and ate them slowly at a small table. Sometimes I ate in the red dress for no one but me.

The women’s group became a rhythm: folding chairs, coffee carafes, a sign-in sheet that always ran out of lines. I learned how to set boundaries the way you learn a new language—awkwardly at first, then with an embarrassing fluency that made me cry in the cereal aisle for no reason. I learned that loyalty without safety is captivity. I learned that forgiveness without change is a costume. I learned that leaving is sometimes the most faithful thing you can do for love.

A few weeks after the verdict, Aunt Josephine invited me for tea. She lives in a narrow row house with a tiny garden riotous with herbs. We sat at her kitchen table and shared lemon cookies that left sugar on our fingers. “I should have protected you,” she said. “I knew Beatrice was… invested in Scarlet’s shine.” I told her the truth: I wasn’t asking anyone to go back and relive my childhood correctly. I just needed them to stop insisting that what happened hadn’t happened. She nodded and showed me how to pinch basil so it grows sideways and thick.

In late spring the women’s group asked if I’d be willing to speak—just ten minutes—at a monthly meeting about the before and after of #RedAlert. I wrote index cards and then threw them away and just spoke. I told them that posting the photo didn’t break my family. It documented the crack that had always been there. I told them that filing the report wasn’t about destroying my sister; it was about stopping my complicity. Afterward, a teenager with blue hair hugged me and said, “I wore a yellow dress to my cousin’s wedding because of you.” I whispered, “Good,” into her hair like a blessing.

The summer passed in small, good increments: iced coffee, late sunsets, dog-eared paperbacks, nights on my fire escape with Lily laughing too loud for the neighbors. Once, in the grocery store, I ran into Mrs. Thompson. She squeezed my hand and said she had watched Scarlet slap me a hundred times in other rooms with different instruments: a snide comment, a borrowed twenty, a seat taken. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I should have said something then.” I told her she had said something now.

Then, one humid evening in August, my doorbell rang. I checked the peephole and saw Scarlet, alone. I stood there with my hand on the chain, feeling my pulse climb stairs. The restraining order meant she couldn’t be at my door; if I opened it, I would be the one making an exception. I slid the chain but left the door on the latch.

She stood on my threshold without eyeliner, which felt like a confession. “I’m not here to fight,” she said. “I know I’m not supposed to be here. I just… I wanted to say I’m sorry. Not the ‘it was a long time ago’ kind. The real kind.”

I didn’t answer. She rushed to fill the quiet. “I was jealous,” she said. “And I was used to getting away with being jealous because Mom would clean it up. I don’t know who I am without that.” She kept her hands at her sides like she was swearing something in court. “I can’t ask you to forgive me. I can only tell you I’m trying to be better at that food pantry. They like me when I shut up.”

The latch felt very thin. “You hurt me,” I said. “Not just that night.”

“I know.” Her eyes were wet. “I also know you don’t owe me a damn thing.”

There it was: accountability without expectation. I didn’t swing the door wider. I didn’t slam it. “Write it down,” I said. “Send me a letter. Don’t come to my door again.” She nodded, stepped back, and walked away. I watched her until she turned the corner and then stood very still and let my heart slow down.

A week later a letter arrived addressed in careful, unfamiliar handwriting. She wrote three pages: about stealing from Josephine and not making excuses, about the whiplash of being adored and how it made her hungry for a kind of attention that never fills you up, about the slap and the laugh and the look on my face and how she dreams about that look. She ended with a sentence that felt like a hinge: I don’t want to be the main character if the script is cruelty. I put the letter in a drawer and didn’t answer. Some things don’t require response so much as rest.

Autumn eased in. The bookstore’s event calendar bloomed with launches and signings; I moderated a panel on “women writing anger” and said the words red dress into the mic without my voice cracking. After the panel, a woman around Mom’s age pressed my hand and whispered, “I laughed at my daughter once when she cried. I’m going to call her.” I squeezed back and said, “Good,” like I had to the blue-haired girl, because sometimes blessing is a loop you hold open for other people to walk through.

One gray Sunday, Dad called and asked if I’d meet him at a diner halfway between us. I said yes and chose a booth near the window. He arrived with a new tentative around his shoulders. We ordered pancakes we didn’t eat. He told me he’d started seeing a counselor through his union. “I didn’t protect you,” he said, very quietly, like saying it loud would make it less true. “I thought if I kept the peace I was keeping the family. I see now I was keeping Beatrice comfortable.”

He slid a small manila envelope across the table. Inside was a check—not hush money, not a bribe, but his tangible apology for the years he watched me be taxed for existing. “It’s not enough,” he said. “It’s a start.” I didn’t cry. I took the envelope and said, “Thank you,” and we sat for a while watching a man outside struggle open a stubborn umbrella.

Thanksgiving came again whether we wanted it to or not. Aunt Josephine hosted. She invited me and Dad. She did not invite Mom or Scarlet. I brought roasted carrots and a pie Lily swore was foolproof and somehow still cracked. We went around the table saying one thing we were grateful for. I said, “Doors that close and also open.” No one laughed at the metaphor. After dinner I helped Josephine wash dishes and she showed me how to get wax out of a tablecloth with a paper bag and an iron, and I put that knowledge somewhere near the basil.

In December, the women’s group asked if I would help coordinate a holiday drive for a domestic violence shelter—gift cards, warm socks, new pajamas with tags. The night before delivery, a volunteer dropped off a box with a note on top: From someone who finally learned to say I’m sorry the right way. The handwriting looked familiar. I didn’t have to name it to accept the gift.

The new year arrived quiet as a cat. I rearranged my apartment plant by plant until the room felt like it could breathe with me. I applied for a scholarship the bookstore offers to part-time staff and picked up an extra class at the community college: Creative Nonfiction. On the first day, the professor asked us to write a list of moments that had re-written us. I put: red dress, slap, laugh, post, door. I didn’t explain. I didn’t need to.

Spring brought crocuses and a text from an unknown number: This is Mom. I know you don’t want to hear from me. I am trying to learn. I joined a group. I won’t ask you to respond. I am sorry. I stared at the words for a long time. They didn’t heal anything. They also didn’t hurt. Sometimes progress is a message that expects silence.

When the anniversary of the dinner arrived, I didn’t mark it with a post. I invited Lily and Jen and Matt over. We made pasta, the cheap kind that tastes like home when you add butter and garlic and too much parsley. We ate at my table and told each other one brave thing we’d done that year. Matt asked if I’d ever wear the red dress again. I said, “I wear it all the time,” and everyone laughed because they’ve seen me cooking in it.

Sometime that summer, the women’s group nominated me to sit on a small advisory board for the shelter. It meant more meetings and fewer nights off, and I said yes. One afternoon, sitting under a buzzing fluorescent light with a clipboard, I realized the quiet joy of making rooms safer for strangers than any room had been for me. It didn’t erase what I’d lost. It made use of it.

Months later, I ran into Mom at the farmer’s market. She stood beside a pyramid of peaches, her hair a little grayer, her posture smaller. For a second I was a kid again, straight-backed under a spotlight I hadn’t asked for. Then I was me now. She said my name like a question. I said hello. We didn’t hug. She said, “I’m reading a book about breaking cycles.” I said, “I hope it’s good.” We stood there, two women who had finally learned that love without respect is performance. We wished each other well and kept moving.

Here’s what didn’t happen: We didn’t all cry and reconcile in a swoop that would make good TV. Scarlet and I are not best friends. Mom and I don’t swap recipes. Dad and I didn’t become a Hallmark commercial. What happened was smaller and truer: I took my life back and kept it. The family adapted to the new weather or stood in the rain.

On a cool September evening, I pulled the red dress off its hanger for no reason at all. I poured a glass of seltzer, put on a record Lily found in a free box, and danced in my living room with the curtains open and the moon catching on the glass. I felt the tender pull of the seam I had mended with my own hands. I touched my cheek and felt only skin.

This is the ending, clear as I can make it: My sister slapped me for daring to be seen. My mother laughed. I turned that moment into a mirror and made them look. I sent the truth into the world with my name on it. I filed the papers. I drew the lines. I built something sturdy where a bruise had been. I learned that loyalty can be a trap and that love without accountability is just gravity pulling you into someone else’s orbit.

I keep the red dress not as a trophy but as a reminder. It is not just fabric; it is a decision I made and remade: to stand up, to be visible, to refuse to make myself small so other people can feel big. And whenever I slip it over my head, the zipper whispering shut, I remember: I am the person who chose me—and that choice, at last, is the story’s final word.

END!

News

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… CH2

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… Part One The pen…

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… CH2

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… Part One The…

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… CH2

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… Part One The…

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. Part One…

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… CH2

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… Part One The emergency room’s…

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street… CH2

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street……

End of content

No more pages to load