At The Family Party, I Gave My Sister a Sealed Envelope: 6 Months of Covered Rent — But Then…

Part One

I’m Claire Young, twenty-eight, and the problem with being your family’s safety net is that eventually they forget you’re made of rope and fiber and time—they start thinking you’re rubber. You’ll stretch. You’ll bounce. You’ll catch them again and again and again.

Last July, at my sister’s thirtieth birthday party in a loud Italian restaurant in Boise, Idaho, I decided to be reckless in the opposite direction. I’d spent the week doing freelance layouts during the day and revising a tattoo-parlor logo at night, pinching pennies between invoices. When the server set down the tiramisu and everyone sang too loudly, I slid a sealed envelope across the white tablecloth, breathed once, and said, “Jessica, open it.”

Inside was a note—my handwriting as certain as I could make it—and a bank check for $6,000. Six months of rent. A pause. A chance to reset the ledger we never stopped keeping.

She tore the flap, glanced at the number, and smirked. “You think this means you’re forgiven?”

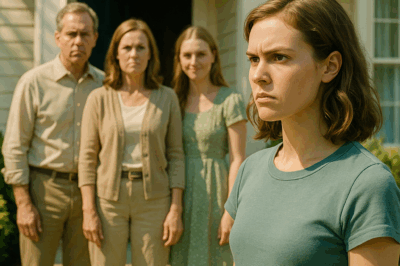

Her voice had that thin, metallic edge I know too well—the sound a mezzaluna makes when it hits the board wrong. The table erupted. My mother laughed, a little too high. My aunt’s wine sloshed. A cousin snorted. It was a chorus they’d rehearsed for years: Claire’s grand gestures are just more proof that she’s trying too hard.

My face burned. My fingers went cold. I reached forward, plucked the envelope back into my palm, and said, very evenly, “Then never mind.”

The laughter died the way a candle dies in wind—sudden and a little ugly. Chairs scraped. The server froze. Five minutes later, voices escalated into something close to a street fight in Sunday clothes, and I understood with a clarity that made every cell of me hum: nothing about this would be the same again.

I stepped outside into Boise’s summer evening, the air thick with heat and road noise. I held the envelope like a fragile animal I had just rescued. Ten years ago, when I was eighteen and working the first of too many coffee shop shifts, I bought Jessica a red scarf I thought looked perfect on her; she opened it, laughed in my face, and said it looked like something out of a thrift store reject bin. I apologized then—I apologized a hundred times, because I hadn’t learned yet that some people collect apologies the way other people collect stamps. The scarf became lore: definitive proof that I was cheap, thoughtless, tacky. Proof that I owed.

The thing about a story repeated often enough is that it becomes a rule. The next decade bent around it. I paid Mom’s electric when she “forgot to budget.” I floated Jessica’s rent when she blew her check on clothes. I paid for Aunt Bonnie’s surprise alternator. Two years. Thousands of dollars. Not one genuine thank you.

Inside, the volume pitched up. Through the glass I saw my mother lean forward, anger sharpening her mouth. “Claire, don’t do this—you’re making a scene.” My aunt tutted. “Loyalty,” she whispered like a curse.

“I’m done,” I said when I went back to the table—loud enough for the whole cluster of us to hear. “No more money. No more bailing you out. I’ve paid enough.”

Jessica crossed her arms. “You’re selfish. You think you’re better than us because you have a job?” Her friend Tamara—always hungry for a front-row seat to someone else’s humiliation—sipped her wine and nodded emphatically.

“Family sticks together,” my mother said, wielding “family” the way some people wield a cattle prod.

“You’ve taken enough,” I said. My voice didn’t shake anymore.

Dad wasn’t there—he rarely is—but his absence has always had the weight of a slammed door. The rest of the table offered me a buffet of words I’ve learned to recognize by sight alone: selfish, ungrateful, cold. I picked up my purse, pushed back my chair, and said, “I’m not your fix anymore.”

“You’ll regret this!” Jessica shouted after me as I walked away. My mother’s voice chased me across the tile—“Claire, please think about what you’re doing”—but the door banged shut, and the night softened around me like a hand on the back of my neck.

In the car, I didn’t cry. I didn’t rage. I put the envelope back in my bag, turned the key, and drove home with my chest tight and my shoulders light for the first time in years. My phone vibrated against the console—Jessica’s name, then my mother’s. I didn’t answer.

There’s a particular kind of quiet that follows a rupture. It makes every small sound sound like a decision. The next week, my phone became an engine of demands. Jessica: You can’t just cut me off. I need help with my car payment. Then: You owe me after that stunt. Mom, more theatrical: Claaaire, we’re struggling. You’re all we have. How could you do this to us?

A message from Jessica pushed me past bemused into furious: Saw this cute jacket online. Only $200. Send it over. I opened my banking app, transferred one dollar, and typed: enough for now. I sent it and let the meaning hang in the air between us like a sign in the wrong language.

Mom called. “What’s wrong with you?” she hissed, voice shaking. “Jessica’s in trouble. You can’t just send her a dollar.”

“I’m not a bank, Patricia,” I said, and the silence at the other end stung more than I expected. She recovered quickly. “You’re breaking this family apart,” she said, and hung up on her own echo.

If a person tells you you’re breaking something by refusing to be used, what they mean is that your function in the machine is necessary for the machine to keep eating you alive.

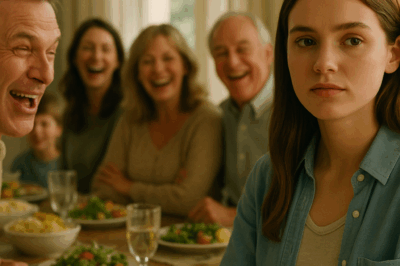

A few nights later, my boyfriend Zachary invited me to a barbecue at his parents’ house on the other side of town. I almost said no; I didn’t want to bring my frayed edges into anyone else’s backyard. But I went, because saying no to everything can become a habit, too.

Their yard smelled like summer dinner—the lazy miracle of burgers and corn on the cob. Zach’s dad, William, flipped patties and made jokes about his secret sauce; his mom offered me lemonade and a plate like she was handing a person permission to rest. Their daughter, Ava—twenty-two, paint on her sneakers, a grin like weather finally breaking—tucked me onto the grass and said, unblinking, “Zach told me what happened. Your family doesn’t see you. That’s their loss.”

No one had ever said that to me before. She handed me a cold cup. “You’re pretty cool, Claire. Don’t let them make you small.”

The thing about being seen is that it feels both brand new and like a thing you should have always known how to accept. We watched William and Zach argue about the grill like they hadn’t had the same argument at every barbecue since 2004. Zach’s mom stacked my plate as if feeding me were a math she could do easily and gladly. Ava asked about my work with the kind of curiosity that makes your answers better. Show me your portfolio sometime. I said yes before I remembered to apologize for anything.

By the time we left, I felt like someone had snuck a weight out of my chest when I wasn’t looking. In the car, Zach slid his fingers between mine and said simply, “You okay?” I nodded. I was, in that precise small way that means a starting point, not a conclusion.

Silence is a relief until it turns out to be a fuse. In September, the doorbell rang while I was sketching at my kitchen table. I opened it to find Patricia on my porch, worry hardening the shape of her face.

“The bank’s going to take the house,” she said before hello, shoulder-sliding past me onto the couch. “I owe $7,000. You have to help us.”

You have to. You are our only hope. The oldest lines in the script.

“I told you I’m done,” I said. “I can’t keep fixing your problems.”

“This is our home,” she said, voice breaking at exactly the right syllable. “Jessica and I have nowhere else to go. You’re our only—”

“You need to figure this out yourself,” I said. “I’m not your bank.”

Her face rearranged itself into something sharper. “You’re heartless.”

“You need to leave,” I said. The words surprised us both with how easy they were to say.

She stood. “You’ll regret this,” she muttered, and the door clicked behind her with a sound that felt like a small mercy.

An hour later: Jessica. Arms crossed, mouth an accusation. “You’re letting Mom lose the house?”

“I’m not paying anymore,” I said. “You both need to take responsibility.”

“Responsibility?” she laughed, bitter and loud. “You’re the one who owes us. You think you’re some big shot with your fancy job. You’ve always been selfish, Claire. That stupid scarf—”

“You’re thirty, Jessica,” I said. “Grow up.”

She flinched—then lunged for cruelty. “You’ll be alone. No one will want you.”

Desperation has a smell; I could have bottled it. I opened my app, sent her two dollars, and typed: time to grow up. Her phone chimed. She looked. She turned the screen toward me like a weapon that had misfired. “Two dollars?”

“It’s more than you deserve,” I said, and watched her leave a dent in the air with the slam of my door.

My hands shook afterward, and then they didn’t. For years, I had treated guilt like a mortgage I could never pay down. The payments felt new and right. Two dollars. A dollar. No more.

In early October, my doorbell rang again. Ava stood there, paint on her sneakers and a rolled-up sheet of paper in her fist. “I made you something,” she said, suddenly shy.

It was a drawing: a Boise street, swooping lines, colors like sunrise. In the center, a figure that looked like me—standing, confident, lit from the inside. “You’re always making cool stuff,” she said, shrugging. “I wanted to give you something back.”

I sat down right there on the floor to look at it properly. No one in my family had ever given me something simply because they had seen me. They took; they called it love. Ava gave; she called it nothing but what it was.

“You’re stuck with me now,” she grinned.

Later that week, dinner at Zach’s parents. Zach’s mom hugged me at the door as if she’d known me longer than she had, and set an extra plate without looking at me like I was an imposition. In the living room, William had a notebook open, sketches spreading across the page like a plan unfurling. “Got a minute?” he asked.

He’s a retired architect with a habit of dreaming that makes you want to help him finish his sentences. “We’re revitalizing the park’s old rec room,” he said. “Community center. Mural. Signage. Maybe a small sculpture if we can scrape. Zach showed me your portfolio. You’re good. Want to take the design?”

“Me?” It came out small.

“Yeah, you,” he said, amused. “We need someone with vision.”

He handed me a folder—actual budgets, actual timelines, actual community board contact names. It wasn’t charity. It was trust.

I spent dinner half listening to book club gossip and half sketching in my head. Ava slid me a napkin across the table with a doodle on it—a messy heart with legs. “You’re going to kill this,” she mouthed. Under the table, Zach squeezed my hand once, the way you do when words aren’t the right tool for the job.

Back home, I laid Ava’s drawing beside William’s folder and opened my sketchbook. Ideas came quick: bold patterns that felt like echoes of voices, signage that didn’t look like anyone was being told to behave, a simple sculpture with room for people to decide what it means. I wasn’t designing for a budget or a board; I was designing for a city I was learning how to love again—and for a girl who had spent too long asking people to bless her with crumbs.

I thought of Patricia and Jessica—how they’d pressed until the glue of my yeses gave out. They called me selfish; here I was, full to the edges with other people’s good ideas and my own hand steady enough to turn them into lines and paint. I fell asleep with a pencil still in my hand.

By December, Boise had put on its cold face for a while, and I was deep into the community center project. William checked in with the kind of feedback that makes you better without making you smaller. “You’re making this place special,” he said one afternoon while we stood in the dusty room that would soon be loud with kids.

An old family friend called, the kind who keeps her ear to the sidewalk. “Claire…I thought you should know. Jessica lost her apartment. She’s working at the diner on Front Street. Your mom’s…behind, too.”

I didn’t ask for details. The pang came—sharp, then gone. For years, their crises had been my sirens. Now they were background noise I refused to let into my house. I placed my hand flat on the sketch I’d been working on and felt the paper warm.

Days later, an email: a new coffee shop wanted full branding—logo, menus, signage, merch. William had shared my portfolio like a proud conspirator. The budget was good. The timeline was the kind that makes you reach for the better pencil.

“You’re killing it,” Zach said, hugging me and making a terrible joke about naming the place Brewed Awakening that made me laugh until I cried. With him, with Ava, with William, I was a person in motion, not a wallet with legs.

My phone stayed quiet. No unknown numbers clawing at midnight. No voicemails heavy with accusation. The silent space where Patricia’s sigh used to live began to fill with other sounds: the scrape of my chair against the floor as I stood to stretch, the radiator clanking itself into warmth, my pencil tapping while I stared at a line and decided whether to keep it.

January slid into February. I stood at my table one night with a map of the Pacific Northwest spread out and a fat pen in my hand. Zach leaned over my shoulder and pointed. “Canon Beach,” he said, grinning. “Weekend getaway. Views for days.”

“Cannon Beach?” I asked.

“Shh, details,” he laughed.

I circled the dot anyway. We booked a tiny cabin. We planned to walk until the cold whipped us awake, eat chowder until our bones forgave us, pretend the whole world only contained us for two days. Ava texted a begging string of emojis: take me in your suitcase. I sent back a photo of a postage stamp and said, Only if you fold.

I’d spent a year prying my life out of other people’s hands and into mine. Here was the proof I hadn’t ruined anything: I could still give. I could give to myself. I could give to the right people.

I used to think family meant give until empty. Now I know it means share what you have with people who add to your plenty. I used to think boundaries were what cold people built to avoid warmth. Now I know boundaries are the frame that keeps the painting on the wall.

As I packed, my phone buzzed. The coffee shop owner’s email: Customers love the brand. More, please. The community center emailed too: Mural unveiling in spring. Bring whoever you want. I put my phone down and looked around my apartment—the table cluttered with markers, Ava’s drawing taped where I could see it when I looked up, William’s folder thick with check marks, Zach’s overnight bag by the door. Choose, I told myself a year ago, hurt and shaking in a parking lot. Choose again, I told myself now, steady and warm.

“Ready?” Zach asked, stepping in with an armful of car snacks.

“More than you know,” I said, and for once the phrase didn’t feel like a wish—it felt like a fact.

Part Two

The night before we left for Canon Beach, Boise glowed cold and bright. I stacked my sketchbooks on the shelf, tucked my laptop into the good sleeve, and watered the succulent I keep forgetting the name of—he is either a Gus or a Hank; I can’t decide. I put Ava’s drawing into a cheap frame and hung it in the hallway because I wanted to pass through her belief on the way out into the world.

The next morning, we drove west with music too loud and a thermos of coffee I forgot to sweeten. The hills folded into each other until they turned to trees, and the trees turned to that gray ocean that always looks like it’s keeping a secret. We didn’t talk about my mother or my sister. We didn’t talk about the party or the envelope. We talked about the way the road looks like a ribbon looped on purpose.

On Saturday night, we built a fire outside the cabin and burned marshmallows we pretended we meant to burn. Stars appeared like they’d been listening for their cue. Zach leaned back in a camp chair and said, “Remember when you thought you had to keep paying to be allowed to sit at a table?”

“Yeah,” I said, staring at the sparks lifting. “I don’t think that anymore.”

He reached for my hand. “Good.”

When we got back to Boise, life didn’t wait; it never does. The coffee shop launched. The community center’s interior finally smelled like paint instead of dust. William walked me through the space with that proud-uncle squint he does. “When the light hits that curve…” he said, pointing at a swirl of color I’d fought the committee for. “They’ll get it.”

A week later, he brought a small group of neighbors by. I watched a woman in her seventies stop in front of the first panel and smile without meaning to. I watched a toddler pat the wall like he knew it was alive. I watched a teenager take a picture with a carefulness that made me want to write a thank-you note to whoever taught him to notice.

I didn’t think of the restaurant. I didn’t think of the envelope. I thought of a girl I used to be who apologized for a red scarf until her apologies turned into a leash, and I thought about cutting that leash one sentence at a time.

Of course the story didn’t leave me entirely. Two months after the unveiling, a DM crawled into my Instagram—an old family friend again. Saw Jessica at the diner. She looked tired. Your mom’s renting a small place. Thought you should know. I sent back a simple thanks and set my phone face down. Once upon a time, that update would have been a summons. Now it was just what it was: information I didn’t have to let decide my day.

Work rolled, then roared. The coffee shop asked me to brand their seasonal drinks because apparently peppermint mochas look “too Christmas” if you lean too literal. William passed my name to a neighborhood association; their park needs wayfinding that works for toddlers and grandparents and everyone in between. I designed a series of little icons with big hats and bigger noses and names I won’t admit out loud. My inbox felt like a thing growing instead of a thing emptying me out.

Zach’s family became the kind of gravity I wanted. His mom started texting me book recommendations like I’d already joined her club; his dad sent me photos of buildings he loves, which is how I found out I love them, too. Ava pinned a new drawing on my bulletin board every month, each one its own dare. She put eyes in the clouds one time and wrote look up in tiny letters where only I would see them.

And then—because stories like tidy circles even when life doesn’t—Jessica showed up where I least expected her to: the community center on a Saturday afternoon in late spring, the room loud with kids painting paper flowers with more paint on their hands than on the page. She stood in the doorway for a long time before she noticed me, as if the room had asked her a question she didn’t know how to answer.

“Claire,” she said, and it wasn’t a shout. It wasn’t even the beginning of one. She looked smaller than I remembered, the way people look when they’ve run out of air and decided to admit it.

I wiped my hands on a rag—blue into green—and said, “Hi.”

Silence is a kind of language when you let it have a turn.

“I lost my place,” she blurted at last. “I got a job. But it’s…you know.” She didn’t have the words for “hard” that weren’t coated in self-pity, so she stopped.

“I heard,” I said. “I hope you land okay.”

She looked at the mural without facing it, like staring is how the truth might change shape. “I was awful,” she said, to the air to my left. “I don’t know how to…you know. Undo.”

You can count apologies by how many “buts” they do or don’t need. She didn’t add one. She didn’t ask for money. She didn’t ask for coffee. She just stood there holding out a tiny match and waited to see if I had any dry tinder left flammable for her use.

“I believe you’re trying,” I said. It was true. “I don’t do loans. I don’t do rescues. I don’t do late-night drives across town to sit on your floor while you cry. But if you want a list of places hiring? If you want a link to a budgeting class the center hosts on Tuesdays? I can do that.”

She blinked like I’d offered her soup when she’d asked for a check. “Okay,” she said, and the word sounded like a foreign currency she wasn’t sure would spend.

I texted her a list. She stared at her phone as if she didn’t recognize it. Then she looked at the wall properly for the first time. “You did this?” she said.

“With a lot of help,” I said. “That’s the good part.”

She nodded, the kind of nod that means noted. “The scarf,” she said, abrupt. “It wasn’t about the scarf. I was mean because you were kind, and it made me feel…less.”

For a second, something old and tender tugged. I did not pick it up. “I know,” I said. “I’m going to get back to the paint.”

She hovered, then left. I didn’t watch her go. I pressed a palm against the wall where the blue met the green and felt the cinderblock hum with the day’s heat.

That night, I told Zach the truth about the moment—no neat edges added. He nodded the way he does when he understands that the thing you didn’t do matters as much as the thing you did. Later, a text from Jessica: Thanks for the list. Period. No emojis. I put my phone face down on the arm of the couch and fell asleep during the second act of a movie that didn’t deserve my full attention.

Summer edged in again. The coffee shop launched another drink with a name I fought to keep from pun territory. The park wayfinding passed city council without anyone trying to turn my little hat guys into a political problem. William and I started walking the neighborhood on Sundays because he says design is mostly “listening to the corners.” Ava painted eyes on a traffic box and got yelled at by a man with opinions about art; I bought her a milkshake and taught her the magic sentence, “You might be right,” as a shield.

In August, Zach’s mom hosted a small dinner and insisted I bring my “big unveiling outfit,” which turned out to be a joke and also not a joke: she presented me with a small framed article from the local paper about the mural. The headline made me wince; the photograph made me proud. William handed me a cheap plastic trophy he’d had made at a shop that still smells like the 90s; it said NEIGHBORHOOD COLOR BOSS and I laughed so hard I had to put my head on the table.

On a Tuesday evening that didn’t feel special until it was, I closed my laptop on a finished invoice and looked around my apartment and realized I hadn’t thought about the envelope in a long time. I pulled it out of the drawer where I’d tucked it after taking it back at the restaurant. The check had yellowed at the edges; the note still read, six months of rent. I tore it in half, then in quarters, and didn’t feel dramatic doing it; I felt accurate.

A week later, an email came through the community center’s site: Would you speak at our boundary-setting workshop? People know your story. It would help. I wrote back, Yes. But only if I can tell the part about how hard it was. They wrote back, Especially that part.

The night of the workshop, the room filled with faces that looked like mine and faces that didn’t, all of us carrying versions of the same tangle. I told them how it felt to be the family ATM with lipstick and a smile. I told them about the one-dollar transfer, the two-dollar transfer, the words time to grow up typed with the kind of shaking hands that make your phone correct it three times before you win. I told them about the envelope across the table and the way a laugh can become a life if you let it. I told them about Ava’s drawing and William’s folder and Zach’s hand and how family is a verb you get to define every day.

When I finished, a man in the back raised his hand and said, “How do you know when you’re being strong and when you’re being cruel?”

“You won’t, at first,” I said, and saw the room lean forward. “At first, it all feels the same. Use three tools: your numbers, your body, your future. Numbers don’t lie. If the math says you’re sinking, you’re sinking. Your body knows—if your shoulders rise when a certain name lights your phone, listen. And your future? Picture the person you want to be in a year. Does today’s yes make her smaller or bigger? Answer that, and act accordingly. Then try to forgive yourself for the days you guess wrong.”

Afterward, a woman with tired eyes hugged me and said, “I sent my brother two dollars last week.” We laughed the kind of laugh you only learn when you stop apologizing for protecting your own oxygen mask.

Fall came soft and gold. One early evening, Zach and I stood in the park looking at the mural as the light slanted just right and the colors did the trick I’d hoped for. Kids ran past, the small messy miracles that all good public spaces generate. A woman I’d never met touched my elbow and said, “I come here when it’s hard. Thank you.” I said, “Me too. You’re welcome,” and meant both.

Later that night, a letter slid under my door. Plain envelope. No return address. Inside: I’m sorry, in my mother’s neat script. No demands. No but. No stamping of feet. I put it in the drawer under Ava’s early sketches and took exactly one breath of the kind of relief you ration. Then I texted her two links: one to the budgeting class at the center, one to a tenant-right resource. She wrote back: Thank you. No emoji. Good.

The next morning, I walked through my apartment and touched three things on purpose—the framed article, Ava’s drawing, and the cheap trophy that makes me laugh every time I look at it—before I locked the door and headed to the shop to meet a client who wants a logo that looks like a hush. Boise was the kind of blue it gets once a year. I passed the Italian restaurant where last July that laugh cracked something open. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t gloat. I nodded at the building like you nod at an old teacher in a grocery store and kept walking.

Here’s the ending, precisely as clear as I can make it: at a family party, I gave my sister a sealed envelope with six months of rent. She smirked, asked if it bought me forgiveness, and the table laughed. I took it back. They called me selfish; I said no; I sent a dollar, then two; I learned that boundaries are not fences built to keep love out—they are doors hung straight so love can come in without breaking the frame. I lost the version of my family that required me to disappear to be acceptable. I gained the version of a life where people hand me napkins to sketch on, email me real budgets, and save me seats because they like me, not because they need my wallet.

I still design for the coffee shop. The community center still smells like kid-paint and possibility. Zach still argues with his dad about grills. Ava still tapes drawings to my wall like prayers. Patricia writes sometimes; I answer sometimes; we are trying to learn a new language without translators. Jessica sent me a photo last week of a small studio: First month paid, she wrote. I replied, Proud of you, and put my phone down like it wasn’t on fire.

If you’re waiting for the people who keep taking to tell you that you’ve given enough, you’ll be waiting until your hands are empty. Decide. Say no. Hold your yes for the places where it makes you bigger. And if you ever have to take an envelope back across a table, do it. Some endings are their own beginnings.

END!

News

On My Birthday, My Dad Texted: “Don’t Expect Anyone To Show” Then I Saw The Group Photo: All… CH2

On My Birthday, My Dad Texted: “Don’t Expect Anyone To Show” Then I Saw The Group Photo: All… Part…

My Parents Didn’t Come to My Graduation — They Said “No Time,” but They All Went to My… CH2

My Parents Didn’t Come to My Graduation — They Said “No Time,” but They All Went to My… Part…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Kicked Me Out Of The House Just For Defying My Sister. CH2

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Kicked Me Out Of The House Just For Defying My Sister — So I……

My Parents Gave My Sister a $860K Home. Then, They Came to Take My House. But When I Refused… CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister a $860K Home. Then, They Came to Take My House. But When I Refused… …

At Family Dinner, My Dad Sneered, “Still Living Off Us” The Whole Family Laughed And Then… ch2

At Family Dinner, My Dad Sneered, “Still Living Off Us” The Whole Family Laughed And Then… Part One I’m…

My Parents Mocked Me at My Sister’s Wedding — But Everyone Went Silent When My Husband Arrived. ch2

My Parents Mocked Me at My Sister’s Wedding — But Everyone Went Silent When My Husband Arrived. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load