At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door

Part One

It had been twenty-four hours since I walked out of that restaurant—heels echoing against marble, mascara bleeding into the corners of my eyes, birthday cake untouched. The laughter still rang in my ears. Only it wasn’t with me. It was at me.

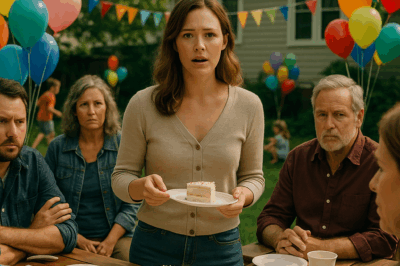

My name is Elaine Harper. I’m forty-two, and yesterday was my birthday. My husband, Greg, thought it would be charming to orchestrate a family-and-friends dinner at the Magnolia Room, that glass-and-gilt temple on King Street where the servers know your mother’s maiden name and the maître d’ remembers your child’s piano teacher. It was “to celebrate me,” he’d said with a grin he keeps in his desk for clients. He stood, tapped a fork against a flute, and called for the room’s attention.

“To Elaine,” he said. “A disaster in heels who can’t even keep her own house clean.”

A ripple of laughter moved across the tablecloths like champagne gone flat. Someone clapped. Somewhere, cutlery chimed. Beside him, Lorenza—blonde, flexible, twenty-six—arranged her napkin like a stage cue and blew him a kiss after she performed the dance he described as “just entertainment.” Greg didn’t flinch. He didn’t even pretend to be embarrassed.

I smiled. I nodded. The plates were cleared. I left my own birthday dinner without making a sound.

I did not run home. I did not run anywhere. I drove until my hands stopped shaking, then I drove to the only place I could think of where the silence might not feel like punishment: my mother’s old apartment. I unlocked the door and collapsed onto a couch that still remembered her shape. The room smelled like lavender sachets and boiled potatoes, the particular fragrance of a woman who could stretch $20 and love enough for three people into a week.

I don’t smoke, not really. Only in moments like this when the world jerks hard in one direction and you need something to steady your body until your mind can catch up. The cigarette burned to the filter before I realized it, singeing my finger. I laughed at myself because there was no one else left in the apartment to scold me.

“How did I let it get this far?” I asked the night. The cicadas had no response.

My mother died seven years ago, but this kitchen in late August still breathes with her opinions. “Don’t embarrass a man in public, Elaine,” she’d say. “Even if you’re right, be kind.” I had been kind for twenty years. I had swallowed jabs and smoothed edges and given my best energy to a man who believed his worst moods were my job to correct.

Greg used words to control me. He never yelled; he didn’t need to. A sigh directed at a dusty shelf. A joke at my expense in front of his boss. “Babe,” he’d say for the photos, the word curdled with the knowledge that he could go whole days in private without saying my name. I hosted dinners, sent thank-you notes, ironed shirts, packed lunches, listened to Rachel’s teenage heartbreak and calculus rants, and I endured.

There’s a difference between enduring and being erased. You don’t notice the shift at first; then one afternoon you’re staring at your reflection in the microwave door and the face looking back at you is older and tired and somehow sharper, too. There was grief in my eyes that night, yes, but beneath it: resolve.

Because Greg’s cruelty yesterday did not arrive whole. It was made of small things he’d been collecting: a letter, a rumor, a name he did not understand. When he stood up to toast my humiliation, he thought he was punishing me for something I hadn’t done. That nameless poison I’d felt on his breath lately had a name after all. The letter that arrived three months ago whispered it into his ear. Noah.

I learned about the letter from Melissa, my best friend since high school, who still knows more about me than anyone should and loves me anyway. She said she’d seen Greg’s face that week at their office building—cold in a way that made the lobby feel like a meat locker. She assumed he’d gotten bad news. He had. It just wasn’t the news he thought.

He thought I was having an affair.

He thought the name Noah was a man in a hotel room. He thought details on three typed pages—dates, places, times—were evidence. He did not know the only hotel room I ever shared with a man named Noah was a hospital room when I was fifteen and terrified and my parents needed a clean place to wash their hands of me.

Noah was never my lover. He was my son.

It happened the way terrible things happen to girls who think love is supposed to be more than it can afford. Michael lived in the next unit. We were inseparable because poverty throws you into intimacy like a lifeboat. We fell in love the way teenagers do: too fast, too loud, too much for parents who measured righteousness by distance between doorways.

When I told him I was pregnant, we planned like fools. We would run. We would work. We would make this small life into a country we could build together. Our parents did not ask what we wanted. They made phone calls. He was sent to Nebraska to live with his grandmother. I was sent to a clinic with a name that sounded like charity and instructions that sounded like threat.

I did not get to hold him. A nurse with kind eyes squeezed my hand. My mother stared at the wall. The doctor did his job. They wheeled him away and told me I’d thank them someday. I have not.

I learned to keep secrets that day. I kept this one so well that I forgot how to open it even for myself. I married Greg at twenty-two, not for his money (there wasn’t any), not even for his charm (there was so much), but for the stability he wore like cologne. He raised a staff for me and called it security. I built a house on it, anyway.

So when the letter arrived and Greg began asking weird questions and looking at me like I had failed an exam I didn’t know I was taking, something in me recognized the shape of a reckoning. Not with him. With myself.

I slept badly that first night in my mother’s apartment. When I woke, my back ached from the couch and my throat tasted like smoke and coffee. My phone was an unlit room: no missed calls from Greg, not even a where are you? The absence didn’t sting. It clarified. I was gulping down coffee when the knock came—polite, patient, like someone asking a favor they have thought about for a long time.

He looked like a memory standing on the threshold.

“Elaine Harper?” he asked. Light brown hair that had decided for itself which direction to go. Eyes that should not have been familiar and somehow were. He held a worn envelope like a passport.

“I’m Noah,” he said. “Noah Hartley. I think… I think I’m your son.”

The world tilted. The porch rose to meet me. Then there was nothing.

When I woke again, I was on the couch with a glass of water sweating on the table. Noah knelt nearby, looking like a man terrified he’d broken something priceless. He helped me sit. I reached without thinking to touch his cheek. The shape of Michael’s jaw lived there, sharp and sure. “You’re real,” I said, because I had to say it out loud to believe it.

“I’ve been looking for years,” he said softly. “Your name was redacted in the files. But I had clues. A nurse remembered. A woman named Rose Hartley—she ran the children’s home—I took her name. She told me about the day I came in. How young the mother was. How scared. She didn’t judge you. Neither did I.”

He did not come to accuse me. He did not come to drag me into a courtroom with the past as an exhibit. He came to see my face. He came to tell me his exists.

“I don’t want to disrupt your life,” he said. “I needed to see you. If you never want to hear from me again, I’ll go.”

“No,” I said too fast. “No, don’t—” The old instinct to apologize for need rose like a tide. I swallowed it. “Stay,” I said. “Please. Stay for coffee. Stay for… anything.”

We agreed on a DNA test because Melissa demanded we be women with proof, not feelings. At the lab, the nurse swabbed both our cheeks, and I thought about how fast even large things happen when paperwork is involved. “Five days,” she said, and handed me a card like a sentence. I couldn’t wait for the phone call. I already knew.

Noah brought tulips because the universe likes tidy symbolism and because he is not a man who expects women to do all the work of gestures. He laughed easily. He hated tomatoes. He loved old records and the way a hand-me-down shirt can feel like a story. He worked as a trauma nurse, which told me more about his spine than any test result ever could.

The lab called on a Thursday morning. “Greater than ninety-nine point nine nine percent probability,” the woman said in a voice she trusted not to sound cheerful. I cried on my mother’s back steps—not the tidy crying you see in films. The messy kind, the kind that clears a field.

I told Rachel the truth that night. We sat in a café by the waterfront where she used to eat peppermint bark after ballet recitals. She is twenty and feels too much and keeps none of it to herself. “I have a brother,” she said slowly, the words trying on her tongue like a new dress. “His name is Noah,” I said. “I was fifteen.”

She looked at me like she was seeing someone she loved from a new angle. “Can I meet him?” she asked.

At Melissa’s on Saturday night, string lights humming under cicadas, Rachel hugged Noah the way brave girls hug new maps. “I didn’t even know I was missing this,” she said into his shoulder, and both of them laughed through tears at the simultaneous truth and ridiculousness of the sentence.

I wrote to Michael. I didn’t know where to begin, so I began with his name. I told him everything and nothing, because there is no letter long enough to bridge thirty years. He called two weeks later. “Elaine,” he said, and I almost dropped the phone because his voice hadn’t changed. He teaches history in Sonoma. He had married once and divorced without children. “I read your letter a dozen times,” he said. “I thought you were gone.”

“I thought you’d stopped wanting to hear me,” I said.

We met at an inn outside Napa because America likes to give you vistas when you do scary things. He stood on a porch holding marigolds—a teenage boy’s idea of romance matured into good taste. He looked like the all of him had weathered evenly. We did not run. We walked. He touched my hand like a question. I nodded like an answer.

When Noah stepped around me and Michael saw him, a sound came out of him I’d never heard—a grateful, scared laugh that tried hard not to sound like a sob. “I never stopped hoping you were out there,” Michael said. “I never stopped hoping you’d find me,” Noah said.

I watched them with the kind of wonder you can only afford after grief. In that moment, the worst thing that had ever happened to me made room for something that felt like mercy.

Greg did not handle mercy well.

He called more than once. He preferred texting. He showed up at my mother’s apartment because embarrassment doesn’t teach certain men etiquette. “You weren’t returning my messages,” he said in the posture of a person who believes being ignored is violence.

“I wasn’t planning to,” I said.

“You don’t get to rewrite the past,” he snapped when he learned Rachel had met Noah. “You don’t get to drag some stranger into this family like nothing happened.”

“There is no family,” I said. “You made sure of that last night at the restaurant.” He started listing my sins: lies, secrecy, teenage decisions. It was like listening to a boy try on his father’s anger for size. “I didn’t lie,” I said. “I survived. You don’t get to weaponize the worst day of my life to avoid accountability for the worst day you created on purpose.”

He threatened court. I opened the door. “You can have the house,” I said. “I’m building something better.”

He froze—not at my refusal to fight for walls, but at the strange fact that I no longer believed I needed them. He left.

That night, beneath string lights and a sky the color of old velvet, Noah asked, “Do you want to tell him? Michael?” I did. Michael came. Rachel brought lemonade and a thousand questions. Noah sat beside his father on a porch swing that creaked like memory and told him the name of every nurse who had ever taught him how to stand in a room full of need and not flinch.

I watched the men I loved fail to apologize for years learn how to say I’m sorry in a sentence that meant I will show up next time. I watched Rachel teach me how to be brave without acting brave first.

I slept for eight hours for the first time since the dinner.

Part Two

Six months later, if you believed appearances, nothing had changed. Charleston still did its hot-and-charming act. The lemon tree in my yard flung itself at the air. Greg still existed somewhere in the city where men believed their reputations were a kind of weather they could control.

Everything had changed.

Let me say how in the language I’ve learned to trust: lists.

- I sold the house. Quietly. Cleanly. We had bought it in a season when Greg still brought home tulips and borrowed joy from the future. It had too many echoes now. I packed what belonged to me and to Rachel—books with our smudges in them, photos that held love and not performance, her childhood drawings that still held glue-gun glitter—and left behind furniture Russell insisted on because the magazine said so. We found a craftsman near the water where the air arrives before the ocean ever does. Melissa brought throw pillows. Noah installed a porch swing. Michael mailed a box of vintage history books with a note inside:

For when you’re ready to start again.

- I put the note on the fridge.

- Rachel moved with me by choice and not fear. She teaches part-time now, spends the rest of her days working at a communications nonprofit that amplifies girls’ voices. She made me a sign for my office with her serious face and then laughed at herself when she hung it crooked.

Harper & Co.—Transitions & Tides.

- “It sounds like something that could help women and also sell farmhouse tables,” she said. “Exactly the vibe.”

- Noah comes by with his adoptive mother, Rose, on Sundays when he can. She is the kind of woman who makes apology into apology and not excuse. “I raised him,” she told me, full stop. “But I always hoped he’d find you.” She calls me Elaine and then sometimes

ma’am

- when she forgets, which makes me laugh because she’s earned the right to not call me that.

- Michael visits every other month with marigolds because he believes in continuity. We walk the length of the pier. We eat sandwiches. We tell the truth like an exercise. There is no grand reconciliation. There is the soft, steady return of trust in a body that once learned it couldn’t afford it. Sometimes he holds my hand like a habit. We are not naive. We are not dramatic. We are careful, the good kind.

- Greg called less. He texted more. The last I heard, he had tried to fill the hole humiliation carved out of him with a startup whose marketing copy looked like a parody of itself. Tessa is dating a real estate developer in Mount Pleasant who does not view women as a part-time job. The world does not take notes, but it does keep score.

And then there was this: the door.

My new house has a front door that sticks in humidity the way old houses insist on teaching you patience. I stalled it with a wedge. The night everything felt finished, the family dinner that had started this finally found its bookend.

Not at a restaurant. At my house.

We’d planned it long before it became poetic. Rose made pot roast. Melissa brought a ridiculous trifle that leaned but did not fall. Michael arrived with marigolds because of course he did. Noah carried in a box of old records. Rachel swore she’d do the dishes and then didn’t and we all forgave her.

We sat elbow to elbow at my table, the kind of sitting you do when there’s history in the room and you’re all determined to arrange it into something you can swallow. We ate. We laughed. We forgot to pretend.

The doorbell rang.

No one stood to answer it at first. Then Rachel looked at me. “I’ll get it,” she said, because she is always braver than she feels.

She pulled the door open. I watched from the table, napkin in my hand like a prayer flag. Greg stood on the porch where he did not live anymore, in a suit he had not paid for yet, with a jaw so tight it had to ache. He had that look men get when they come to collect something they’re sure the universe still owes them.

He stepped forward—and froze.

Noah stood behind Rachel. Michael came to the threshold because habit sometimes outruns intention. It was startling, even to me, how visible their resemblance was—the way Noah’s brow creased exactly like Michael’s, the way they both cocked their head when confused, the way their stance said we without rehearsal. Greg’s eyes flicked from one to the other like a tennis match. His mouth opened and closed twice. He couldn’t find a shape total enough for what he wanted to spit.

“Evening,” Michael said, and did not offer his hand.

Greg’s gaze slid past them to the table, to Rose who nodded at him like a queen acknowledging a peasant she did not fear, to Melissa who crossed her arms, to me, who did not stand.

“What is this?” he asked, but his voice didn’t carry.

“This,” I said, staying seated because the days of me rising for his comfort were done, “is a family dinner.”

“You humiliated me,” he said, as if naming a feeling could make it true enough to matter.

“A year ago,” I said, “you stood up in a room and told strangers I was a disaster for sport.”

He bristled. “I know about your bastard son.” He said the word like he’d saved it for maximum injury.

“Do you?” I asked, my voice quiet and even. “Look at his face, Greg. Then tell me if this is a bastard, or a man who exists despite you.” He didn’t look. Or maybe he did, and that was what made him freeze to begin with.

He took a step into the doorway—and hit the wedge.

“Don’t,” Rachel said, and it wasn’t a plea. She had my voice that night, the one that had found me under lavender and grief. “You’re not welcome here.”

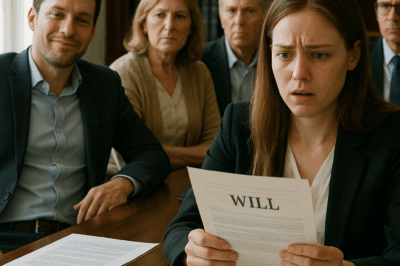

He stared at her. He tried Dad on his tongue, the word sounding like a person he used to be. She did not soften. She did not look to me for permission. He opened his mouth again; the sound of paper interrupted him. Someone behind him cleared his throat. “Mr. Delane?” A man in a cheap suit held out an envelope. “You’ve been served.”

Greg looked at the process server as if he were part of a magic trick he hadn’t rehearsed. “What is this?” he asked again, smaller this time.

“Restraining order,” the man said. “Financial disclosure. Court date.” He pointed at a line like he had done this a thousand times and enjoyed it never.

Greg held the envelope like it burned. He looked past us into the home that had nothing to do with him anymore. He looked at the table where a group of people who had chosen each other were about to pass a bowl of mashed potatoes he didn’t deserve. He looked at his own hands. He stepped backward, bumping into his own consequence, and left.

The door shut with that sticky sigh old houses make—the kind of sound that isn’t a slam, isn’t a whisper, just a line drawn clean.

We stood there for a breath. Then Rose said, “The pot roast is getting cold,” and Rachel rolled her eyes in relief and Melissa said, “God, yes,” and Noah put a record on and Michael set the marigolds in a jar and I sat back down.

We ate. We laughed. We were quiet together without fear. I did the dishes with Michael at my elbow because some domestic things feel like sacraments when you haven’t had them in a long time. Later, when everyone had gone and Rachel was asleep in the guest room with the sound machine she swears is classy and is not, I stepped out onto the porch. The air smelled like salt and rosemary. The new door clicked behind me in a way that said it was doing its job.

I looked up at a sky so clear it felt like reassurance and thought about the woman in the microwave door—tired, hollow, sharp as a tack. I thought about the girl in the clinic whose mother called silence love. I thought about the wife at a white tablecloth, the mother in a bleacher, the woman on a back step with a lemon tree. I thought about the moment at the threshold when a man stopped moving forward because he finally saw something he could not control.

People ask whether I forgave him. That isn’t the word. I set him down. I set down the weight of his moods, his financial messes, his appetite for humiliation. I set down the idea that being loved meant being small. I set down the belief that knowing a story meant you were obligated to stay in it. Then I picked up my life. That’s the opposite of hate.

I still have the cream envelope in a drawer, not because I need to remind myself of the way it felt to slide it across a table, but because sometimes tangible things help you narrate the truth back to yourself. The truth is this: he humiliated me and I did not die. The truth is this: my son knocked on my door and I fainted and then I woke up. The truth is this: my daughter hugged a stranger and called him brother and meant it. The truth is this: the man I loved when we were children came back as a man and we took a walk. The truth is this: at a family dinner in a house that is mine, my husband humiliated me—and everyone laughed. But later, at a door that sticks in the summer, he froze. And I did not.

I walked back inside. The record skipped once and smoothed itself out. I switched off the porch light and left the door ajar for the night air to find its way in.

END!

News

At My Brother’s Wedding, I Was Given a Folding Chair by the Kitchen… ch2

At My Brother’s Wedding, I Was Given a Folding Chair by the Kitchen… Part One My name is Adrien….

At My Nephew’s Birthday Party, I Said, ‘Can’t Wait For The Big Family… ch2

At My Nephew’s Birthday Party, I Said, “Can’t Wait For The Big Family…” Part One My name is Eli….

Found Out My Parents Left Everything To My Brother In Their Will, So I… ch2

Found Out My Parents Left Everything To My Brother In Their Will, So I… Part One My name is…

‘Sorry, This Table’s For Family Only,’ My Brother Smirked, Pointing Toward… ch2

‘Sorry, This Table’s For Family Only,’ My Brother Smirked, Pointing Toward… Part One My name’s Eli. I’m thirty-four. The…

When I Attended My Sister’s Wedding, My Seat Was in the Hallway. MIL Smirked.. ch2

When I Attended My Sister’s Wedding, My Seat Was in the Hallway. MIL Smirked.. Part One My name’s Alex,…

My Aunt Accidentally Sent Me A Video Of My Family Calling Me A ‘Pathetic Failure’.. ch2

My Aunt Accidentally Sent Me A Video Of My Family Calling Me A “Pathetic Failure”.. Part One My name…

End of content

No more pages to load