At my sister’s wedding reception, the screen flashed: Infertile, divorced loser, high school dropout

Part One

The first laugh always sounds like a cough.

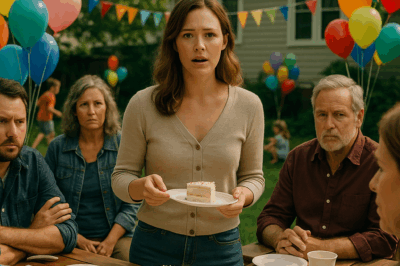

When the words INFERTILE. DIVORCED LOSER. HIGH SCHOOL DROPOUT. popped onto the twenty-foot LED screen behind the head table—clean white font on a blush-pink background—half the room coughed. A second later, laughter rippled over the white linens and gold chargers, a bright, fizzy sound like shaken champagne. Someone clapped. My mother smiled into her wine glass. My father leaned toward the groom’s father and said something that made him smirk. My sister lifted her bouquet like a wave queen and said, “Careful. She might burst into tears.”

I didn’t.

I slipped my phone from the pocket of my midnight-blue dress and, without looking away from the screen, said softly, “Start it.”

Across the ballroom the AV tech—our AV tech—tapped a key. The slideshow stuttered, hiccupped, then dissolved into black.

A new image bloomed: a teal title card, clean and spare, the kind I’d designed a hundred times before at my “low-wage desk job.” UNMUTED: LIVE. Surviving Family Harm. A little red dot blinked beside the word LIVE. In the upper corner, a number spun like a slot machine—276,904… 511,002… 983,411… —then settled over one million.

Silence replaced the laughter like a stone dropped into a lake.

My sister Sloane, white satin and diamond hairpins, turned slowly. Her smile ripened into confusion. “What… is that?”

I stood. Every eye tracked me as I walked toward the small stage the hotel had built for speeches, one hand around my phone like a talisman, the other skimming napkins and flower stems. I passed the floral arch that had cost more than my first car and thought, not unkindly: It’s unfair, how beauty can be welded to cruelty.

I stepped up beside the mic, didn’t touch it, and raised the phone higher, letting the front-facing camera take in the room: the rows of round tables; the head table set for eight; the towering cake with the sugar peonies my mother had insisted on. When I spoke, I made my voice calm, because calm is the sound of a door opening without force.

“Good evening,” I said. “I’m Maya Hart. Some of you know me as Sloane’s sister. Over a million of you know me as the host of Unmuted.”

A hum moved through the room—recognition, denial, curiosity. My mother’s knuckles tightened around her stemware. My father, Conrad Hart, commercial real estate magnate, went very still.

“It turns out,” I continued, “that one person can be more than one thing at once.”

Behind me, the number blinked again: 1,204,337.

I didn’t say I told you not to do this. I didn’t say I asked for one night free of it. I had asked, last week, when Sloane handed me a laser-printed run-of-show with SISTER’S TOAST (5 MINUTES) penciled in between FATHER-OF-BRIDE WELCOME and SURPRISE SLIDESHOW. I had told her I would not stand in front of 300 people again and polish our family’s myth. She’d smiled, air-kissed my cheek, and said, “Try not to be dramatic, Maya. We’ll keep your part simple.”

Simple. Like a bullet.

“My sister prepared a surprise,” I said, gesturing at the LED. “So did I. Mine’s called the truth.”

Sloane laughed, too loud. “Oh my God, Maya, don’t be pathetic. We’re joking. Everyone knows we love you. It’s all in good fun—”

My thumb tapped the upper-left of my phone screen. On the LED, a waveform bloomed, pale blue lines lifting and falling like breath. A label appeared: HARVEST DINNER, OCT 14—PRIMARY BEDROOM. The first voice was my mother’s, honeyed and bored.

“David did her a favor,” Lila said, lazy with wine. “He married wrong and then corrected course. Men want legacy. Maya’s body couldn’t even manage that.”

The room’s temperature dropped a degree. The wave of oh moved through the room differently this time, lower, unsure. Next came Conrad’s voice, crisp, irritated:

“She never finishes anything,” he said. “Couldn’t carry a baby, couldn’t carry a degree. Sloane’s my real daughter. Maya’s the family charity.”

The waveform flattened.

I let the silence stand. It’s hard to remember that silence can be a tool when you’ve mostly known it as something forced on you. In silence, people have to feel what they’ve said.

My father rose halfway from his chair. “Turn that off,” he snapped. “You had no right—”

“In New York, I need only one party’s consent to record,” I said. “And as the person being discussed as if I were furniture, I consented.”

“Ugh, over one bad joke,” Sloane muttered into the mic, angling her smile toward the uncomfortable donors. “Maya always—”

Another waveform.

LILA to SLOANE—NEIMAN MARCUS SPRING TRUNK SHOW (THAT BATHROOM)

“Don’t worry about Maya’s toast,” my mother said, tinny with tile echo. “She’s incapable of upstaging you.”

A chorus of polite laughter. A second voice—Sloane—giggled. “She’ll cry and people will feel sorry for her. Actually, that would be great for our engagement numbers.”

My mother’s murmur, deep and contented: “Poor little barren thing.”

The waveform stilled. I almost said, I know which bathroom you mean. The one with the good lipstick.

“You’ve all heard the family lore,” I said instead. “Maya, high school dropout. Maya, divorced because she couldn’t give her husband a baby. Maya, low-wage desk drone. ‘We tried so hard with her,’ right? ‘She makes choices we don’t understand.’”

I turned my phone around so the front camera caught the expressions at my table: my mother’s flush bleeding beyond her contour, my father’s tight jaw, Sloane’s reed-thin smile collapsing.

“I didn’t drop out,” I said. “I left senior year to work full-time after my father refused to co-sign my FAFSA because ‘we don’t do debt’—this while leveraging eight-figure credit lines at his firm. I finished my diploma at night. I finished my degree online. I am not infertile. My doctor says there’s no reason I can’t carry a pregnancy to term. We didn’t divorce because I failed at anything. We divorced because my ex-husband couldn’t be married to a woman whose family treated her like a mistake.”

“Don’t drag me into this,” Sloane said brightly, which is a thing people say when you’re already there.

“He asked me to leave,” came a new voice, steady as a mezzanine beam—the man stepping into the room, tall in a navy suit, the fitted kind he’d never have owned when we were 25: Daniel Wolfe, my ex-husband. Every head turned. He stopped at the edge of the dance floor, hands at his sides like he was entering a witness box without a lawyer, and said, voice carrying, “Because every time Lila called Maya a problem, I didn’t defend my wife. The thing I’m ashamed of in that sentence is the reflexive my.”

He wasn’t on my run-of-show. He wasn’t on my contingency list. But when I had told him last month what I planned to do—when I’d said, voice small at midnight, I’m tired of it—he’d said, “Tell me how to show up for you in a way that isn’t about whether I’m allowed to call you at 2 a.m.” I told him where to be if he wanted to be there. He had not promised. He had arrived.

It would be easy to make him the hero right now. He didn’t need to be. He had a part and picked it up and that was it.

“I am a clerk,” I said, looking at my father, because yes, that’s how they’d filed me away. “I also run Unmuted, which was my anonymous YouTube channel until eleven minutes ago. We are 1.3 million strong today. We’ve connected survivors of family harm to legal aid, to therapists, to each other. We have funded emergency exits for a hundred women. We file taxes. We pay salaries. We are not a hobby.”

Sloane’s laugh was a sound a person makes when they can’t find the wall. “One point three million? on the internet? That’s probably bots.”

The number on the screen ticked: 1,412,774.

Comments scrolled in the corner: WE SEE YOU. My sister’s wedding was the same. That kitchen audio—my god. I sent this to my mom and she just texted back “call me.” My hands are shaking.

“You’re humiliating us,” my mother said, low, vicious, the same voice she used once when I fell asleep in the back of her car and she met a friend in a parking lot and lied about picking up dry cleaning. “You’re humiliating your sister on her wedding day. For what? So strangers clap?”

“For consequences,” I said. “For anyone who will never have a mic and will never have a room listening. And because your consequences should not always and only be my embarrassment.”

“Family matters belong in the family,” my father snapped. “You want money? Is that it? You and Daniel always wanted money.”

Daniel didn’t flinch. “Not that it’s relevant to your defense,” he said mildly, “but after we separated I took a job in Chicago and did okay. The first check I wrote over $100k was to Maya’s nonprofit. The second was to my best friend Jake after his sister needed a hotel for two months. The third was to a scholarship at my old high school. I’m not a hero. I just put the money where I wish it had been when I was 13.”

Conrad’s face turned the color of raw beef. “This is extortion,” he said to me. “We will sue you. We will ruin you. You cannot brand us abusers and walk away.”

I smiled at him then—small, not unkind.

“I don’t need to brand you,” I said. “I recorded you.”

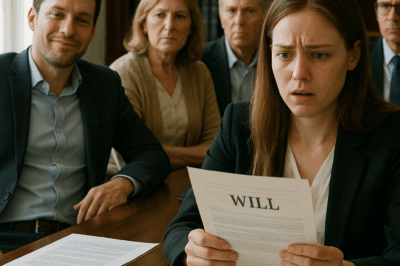

The LED cut again: now not a waveform but text messages, organized by phone number, date, and time. My mother’s threats (“We made you and we can unmake you”), my father’s belittling (“Stop talking like a therapist”), Sloane’s strategy notes for tonight (a list of “jokes”—Slide 12: Do ‘barren’ if the room is warm). The last set wasn’t mine. It was a scan of a letter on Conrad Hart letterhead—a settlement agreement for a nondisclosure he’d tried to slide across my kitchen table when I said I was done writing speeches for them. $75,000 in exchange for her silence on “family matters.”

“Who told you the NDA would shut me up?” I asked. “Did you think I didn’t know the difference between a legal document and a leash?”

“You bring this room down and you bring your own house down,” Conrad said. “Wilson Estates—”

“Your other daughter works at your firm,” I said. “If you’d lifted Sloane up without standing on my neck, we would be clapping right now.”

Sloane’s face flickered—hurt, then hot hate. “You’re jealous,” she said. “You’ve always been jealous. You’re jealous because James and I—”

“You better stop there,” said a new voice, and for a fleeting second I thought my body had conjured a fairy tale. That voice was James’s mother, who looked at me every time we’d been in the same room the way a person looks at a painting they’re trying to place. Now she stood, smooth as a blade. “Because if you put my son inside your cruelty it will end even less well than it already has.”

James’s father touched her wrist and stood too. “Please accept our regret,” he said to me, and every syllable in the word regret hit the floor like coins. He turned to his son. “We will be at the hotel.”

“Dad,” James said. “Wait.”

He looked at Sloane. His face had the stunned tenderness of someone realizing that a woman he loved could also be a woman who said ugly things when she thought the right people were listening.

“I’m not doing this,” he said quietly to Sloane. “I’m not joining a family that mocks a woman’s body as entertainment.”

Sloane stepped toward him. “You can’t be—are you serious?”

“I’m sorry,” he said to me. “This is not about punishing you. This is about not punishing myself.”

He followed his parents out. Sloane’s bouquet sagged to her side. Someone in the back whispered a curse word.

“Okay,” I said into my mic that was not my mic. “Now that we have everyone’s attention, a brief housekeeping note: this livestream is being mirrored to a separate server in case anyone thinks about pulling the plug. We are also taking down statements from those who have experienced harm tonight. There are cards on your table. You can write your truth and slip it to the person with the teal badge. We will handle the rest.”

“Handle?” my father spat. “Handle with your ‘online friends’?”

“With lawyers,” I said, and glanced at the screen where a new message from RUBIN & KESTLER LLP—SUBJECT: DEMAND LETTER READY replaced the waveform. “With boundaries. With the thing I learned to build after your house taught me not to need them.”

There is always a final secret in a family. Here was ours: the rumor of my infertility had been a distraction. The truth—not blame, not shame, not punishment, but truth—was genetic. My father’s sister, my aunt Deb, had died young, an illness that had stained my father’s eyes when he looked at baby pictures of me. A piece of that illness lived in my father’s DNA. It made daughters like me cautious about screenings. It made daughters like Sloane angry at nothing that looked like weakness. It made my father afraid to be told by a doctor that his decisions had consequences.

“Dad,” I said, turning to him as if we were alone in my childhood kitchen, a bowl of grapes between us that he never ate. “I got tested last year. That’s how I know what I carry. That’s how I know what Sloane probably carries. That’s how I know why your sister died.”

The room wavered. My father sat. My mother pressed a napkin to her lipstick. Sloane stared at me as if I had handed her a glass of water she didn’t know she needed.

“That’s why I’m saying this now,” I said. “Not to hurt you. To stop the hurt from being wrapped in ribbon.”

I looked back at the screen. The number ticked again. 1,845,332.

“To those of you watching,” I said, “here’s what happens next: after I step down from this stage, I’m filing a civil complaint for intentional infliction of emotional distress with the recordings you just heard and a hundred you didn’t. My lawyers will file Freedom of Information requests where applicable. My nonprofit will, as always, allocate funds to our emergency grants for those of you who texted that you need bus fare, a room for a week, a divorce retainer.”

I slid my phone into my pocket. “To those at tables ten and thirteen—the Wilson Estates table, the bank table—if you would like to discuss ethical practices moving forward, there’s a number on the back of your place card.”

I stepped away from the mic, and for a second no one moved. Then they did, in that sideways motion humans make when deciding whether to run or pretend they aren’t. Sloane stood alone between two arrangements of white peonies. She looked very small. It occurred to me, with the soft absence of gloating that surprised me, that I had just given her the only gift I could ever give that mattered. It wasn’t forgiveness. It was seeing.

David touched my elbow. “You okay?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “But I’m done.”

He smiled and didn’t try to touch my back like a man shepherding a girl off stage. He just stood with me as the lights came up, the way people do when they understand you have a leg to stand on but your leg is tired.

At the far end of the room, a knot of women with teal badges—my volunteers, my friends—began to collect the cards people had scrawled on. One of them lifted a card and mouthed the words to me across the room. ME TOO.

The first laugh at the beginning of the night had sounded like a cough. The sound now was a sigh—a room full of people realizing they’d been at a magic show and the trick was not that someone was sawn in half but that they’d been asked to clap at the pain.

I walked out of the ballroom and into air that felt like a clean kitchen after everyone leaves, and my lungs pulled it in like I had never done that before.

Part Two

A year is a long time. It is also no time at all.

At the book signing, a teenage girl cried when I wrote Your voice has power on the title page, and I pretended my own eyes weren’t burning as I watched her mother hold her without flinching. At a conference in Chicago, a man in his fifties took my hand for too long and said, “I stopped talking to my daughter when she came out. I thought I was protecting the family. I know better now.” In the studio at NPR, the host asked a question that wasn’t a question—“Do you regret doing it at a wedding?”—and I said, “I regret that I had to do it at a wedding. I do not regret that, because I did, a roomful of people realized they had laughed too long.”

Every story reverberates. The clip of the LED screen blinked through Instagram for six weeks. Sloane took her account private, then public, then private again. The Andersons issued a statement that used the word values six times and grace twice. Conrad Hart, who had once used his full name as a battering ram, took it off three retail developments before his partner took his seat.

The lawsuit settled in mediation after my attorneys produced a list of dates and slurs so boring in its exactness the mediator sighed. We agreed to a statement acknowledging “emotional harm and past conduct that did not reflect the values we wish to live by.” My parents wired the first payment to Unmuted Fund and the second to a trust that can’t be touched by anyone whose last name is Hart, including me without two board signatures. I trusted my lawyers more than my impulse for theater by then.

Sloane moved upstate to a rental that smells like mildew, if her texts are to be believed. For six months she posted postcards of mornings alone with coffee and captions about starting fresh that made me want to send her a space heater. The seventh month, a card arrived at my office in an envelope without a return address. I started therapy, she’d written. I am learning that what I did wasn’t a reflex. I am learning to say “I was cruel” without adding “but.” That was the hardest sentence I’ve ever written. If you want to meet for a walk sometime, I’ll be at the reservoir on Saturdays at nine. If not, I’ll keep walking anyway.

I did not reply for four weeks. Then I went to the reservoir.

She was already there, ridiculous in a parka she’d never have worn last year, with boots that sloshed. We walked without talking for a long time. The first thing she said was, “I’m sorry,” and she said it like a person used to ordering an apology on a menu and was trying now to cook. The second was, “I got tested.” She didn’t need to specify. I nodded. She swallowed. “It would have been better to know years ago,” she said. “It also feels good to know now.”

We walked two miles in a circle and made a plan to walk again the next week. We did it six times before she asked, “Can I come to one of your meetings? There’s a mothers’ group, right? Sometimes I think I’d be less likely to be awful if I knew what women were talking about when I’m not in the kitchen.”

At Unmuted we started calling the Wednesday evening session Practice, because that’s all any of us are doing. Sloane sat in the back row the first time, not because she didn’t think she belonged but because she’d always liked exits. She didn’t talk. She didn’t cry. She listened while a woman in scrubs said, “My mother used to say I was dramatic when I kinked a hose and it sprayed me.” She listened while a teenager whispered, “How do you tell your aunt to stop calling you a phase?” She listened while a man who had been a bishop said, “I’m here because I told my congregation to forgive their fathers. I retired and my daughter stopped calling. I realized I had not taught my church to send money with casseroles.”

At the end Sloane hugged the woman in scrubs. Sometimes stubbornness is desire trying to drive without a license.

Conrad wrote me one letter and did not call. I read your book, he said. I will not say I didn’t know. I will say I didn’t want to know. I saw myself in the chapter about the word “standards.” I am in a men’s group now where no one knows my profession. I know that my work won’t be visible in a way you will accept because the only thing I’ve ever tried to do with you is fix what I broke. But I am doing it anyway. This is not a request. It is an apology. If you want to meet for coffee let me know. You will likely not, and I will understand.

I did not want to. I met him anyway, in the corner of a diner at ten in the morning on a Tuesday where no one would know his name. He looked smaller, not because he was humbled by fate but because he’d stopped trying to fill the room with his posture.

“I don’t forgive you,” I said after the waitress left. “I don’t have to. I also don’t have to spend my life not forgiving you. I can just…I can just make your part in my story proportionate to other parts.”

He nodded like a man reading English as a second language and finally understanding a preposition. “When your mother said those things about your body,” he said, and looked away, and his throat worked. “I should have told her to stop. I can’t understand why I didn’t without hating myself. I have a therapist who keeps asking me who I thought I was protecting. He is tiresome. He is also correct.”

He handed me an envelope. “What is it?” I asked.

“It’s not money,” he said ruefully, managing half a smile. “Don’t worry. It’s the lab my cousin used, the one I wish we’d known about forty years ago. If you know anyone who needs a name that isn’t a brand, you can give them this.”

We split the check. He didn’t try to hug me in front of the rotating pie case. I walked out onto the street and didn’t check to see if he watched me go.

My mother did not write. That is not a tragedy. It is a noun.

Daniel and I didn’t get back together. But he came to every third Wednesday at Unmuted and made coffee and brought real cream because he had finally learned the difference between being useful and being necessary. We were not a romance. We were the thing that’s left when you decide the person who broke your heart will not be the last person who gets to touch it.

The day the trade association for developers invited me to deliver the keynote on Trauma-Informed Housing Policy, I almost laughed. I almost said no out of pettiness. Instead, I walked onto a stage and told a room of men like my father, “You don’t need to become social workers. You need to stop treating neighbors like profit. You need to fund a tenant liaison who is a woman of color from the neighborhood you’re destroying. You need to hire my board member to teach your superintendents to call the hotline instead of pretending the screaming is a TV.”

When I finished, one man—pink scalp, blue suit—stood and said, “All due respect, Ms. Hart, I came here to learn about risk mitigation, not get a lecture on feelings.”

“Good news,” I said, smiling into the mic. “This is risk mitigation. The people you call tenants call the police when you ignore them. In ten years you’ll call it good business. Tonight you can call it saving face.”

They laughed. It wasn’t a cruel laugh. It was one of those laughs people make when they recognize a line that will someday be in a PowerPoint they’ll pretend they wrote.

Sloane and I met at the reservoir every other Saturday all winter. She never once said, “You humiliated me.” She said, “I hate who I am when I feel unsafe.” She said, “I told my therapist it feels like I’m giving up all my good lines.” She said, “My therapist said, ‘Or you’re learning which ones were just mean.’”

She came to a book signing and handed out sticky notes to strangers so they could spell their names the way they wanted them written. She signed up to volunteer at our drop-in clinic and watched a woman with a baby fall asleep in a chair in thirty seconds because for the first time in a week she was in a room where no one needed her. She looked at me like she was seeing a different species and I thought, no, not different, just later.

When spring came, I rented a small hall with terrible lighting and too much air-conditioning and hosted a meeting I’d been avoiding: Daughters & Mothers. I stood in the back while twenty women sat in a circle and said the things I can’t put in a press release. At the break, one woman came over to me, lipstick worn off, eyes wet.

“I watched your video at my sister’s wedding,” she said. “My mom texted me that night and said I’d ruined the family chat. I texted back a link to your channel and said, ‘You can join the new chat when you stop pretending my body is community property.’ She didn’t. But my aunt did. She brought me a lasagna. I didn’t know adults still did that.”

“Adults do that,” I said. “The ones we keep.”

On the anniversary of Sloane’s meltdown—and my beginning—I walked by Manhattan’s Bryant Park and saw a couple posing for wedding photos. The bride had tucked tissues behind her bouquet. The groom adjusted his tie with the gentle, absent grace of a man who wears ties every day and still thinks his collar is a costume. The photographer fussed. The mother-in-law cried like the sky. The bridesmaids were cold.

I hoped they didn’t need me. I hoped their jokes were about shoes.

My phone buzzed. A text from Sloane: I went to Mom’s today. I brought her a plant and said, “I am an adult who can leave.” She said, “You always have been.” I said, “Not like that.” We didn’t fix anything. I didn’t take her jokes. I left when I was ready. It felt like finishing a run.

Proud of you I typed. Reservoir Saturday?

A pause, then: Always.

At Unmuted, we hung a corkboard by the door and wrote LOOK WHAT DIDN’T KILL ME across the top. People pinned rental agreements, court documents, GED results, restraining orders, restraining orders denied with try again scrawled across them, a library card, a picture of a woman smiling beside her new used car, a receipt from a locksmith, a child’s drawing of a house with the people bigger than the roof.

I brought a copy of the program from Sloane’s wedding that wasn’t, and I pinned that up too, not because I needed a trophy but because I needed to remember how close I had come to believing that I deserved that joke.

When I signed copies of my book after a talk in Cleveland, a small woman with nervous hands set her copy on the table and said, “Please make it out to Regina, because my name is not Tina, no matter how often my mother says she forgets.” I wrote, DEAR REGINA, THERE IS ONLY ROOM FOR YOUR NAME.

At a school board meeting in Yonkers, I handed a board member an index card that said, ALLERGIES ARE NOT PREFERENCES, because he’d just said “nut-free tables are a fad,” and I can’t save a world that still thinks peanut butter is a patriotic right. He read it and said, “You want me to say ‘I was wrong’ in public?” I said, “I want you to say ‘I will learn,’ and then I want you to learn.” He did both. The nurse hugged me later.

One night in May, my apartment buzzer rang. I looked at the screen. Daniel stood on the stoop holding a paper bag. I buzzed him up without thinking about story arcs.

“Your favorite,” he said, lifting the bag, “which is also mine, which I think is the same as it used to be.” Pad see ew, extra broccoli. He set the food on my counter. We ate out of cartons like grown-ups pretending to be teenagers.

“For the record,” he said, and stared into his noodles, “I would have come even if you hadn’t asked last year.”

“I know,” I said. “I wouldn’t have asked if I didn’t think you would.”

He smiled. “Do you think you’ll ever do it again?” he asked. “The live drop, the room, the… spectacle?”

“No,” I said. “I don’t think I will ever be in that position again. Family is no longer a room where I have to win to be allowed to sit.”

He nodded and changed the subject because he had learned too.

When he left, he hugged me the way you hug a person you would like to kiss and will not, and I closed the door with a laugh that wasn’t bitter and went to bed in a room where the quiet was mine.

People think a happy ending is forgiveness or a wedding. For me it is neither. It is a Saturday morning when Sloane texts, I’ll be late—bodega cat sat on my lap and I didn’t want to disturb him, and I laugh alone in my kitchen with coffee and an orange. It is an afternoon when my father sits in the back row of Practice without speaking and then puts five twenty-dollar bills in the donation jar and doesn’t look at me. It is a Thursday when my mother doesn’t call. It is my niece sending me a picture of her peanut-free classroom list with the caption I FIXED IT and a hundred heart emojis.

At my sister’s wedding reception, the screen flashed words that were supposed to end me. What flashed next was a life I would not trade for the life on the stage. Sloane and I are not best friends. My parents will never be grandparents in the way people write about in Christmas letters. Unmuted will likely be sued twice next year. A boy in our support group relapsed and we kept his chair empty until he came back.

I used to think freedom was a poster—big, declarative, framed. It turns out freedom is a bulletin board with pushpins. It is a law firm that keeps a folder with your name on it. It is a group chat that says CHECK-IN every night at nine. It is a child who knows to dial 911 and a woman who knows she is not a disgraced daughter just because she stopped eating when her mother runs out of jokes. It is a door that opens inward and outward and a woman who knows how to stand in it.

If you were waiting for a neat bow, I don’t have one. I have the thing that keeps replacing bows: a life. One I chose when I stood on a stage and said “Start it,” because someone had to turn a laugh back into a cough. If that someone had to be me, I was ready.

I still am.

END!

News

At My Brother’s Wedding, I Was Given a Folding Chair by the Kitchen… ch2

At My Brother’s Wedding, I Was Given a Folding Chair by the Kitchen… Part One My name is Adrien….

At My Nephew’s Birthday Party, I Said, ‘Can’t Wait For The Big Family… ch2

At My Nephew’s Birthday Party, I Said, “Can’t Wait For The Big Family…” Part One My name is Eli….

Found Out My Parents Left Everything To My Brother In Their Will, So I… ch2

Found Out My Parents Left Everything To My Brother In Their Will, So I… Part One My name is…

‘Sorry, This Table’s For Family Only,’ My Brother Smirked, Pointing Toward… ch2

‘Sorry, This Table’s For Family Only,’ My Brother Smirked, Pointing Toward… Part One My name’s Eli. I’m thirty-four. The…

When I Attended My Sister’s Wedding, My Seat Was in the Hallway. MIL Smirked.. ch2

When I Attended My Sister’s Wedding, My Seat Was in the Hallway. MIL Smirked.. Part One My name’s Alex,…

My Aunt Accidentally Sent Me A Video Of My Family Calling Me A ‘Pathetic Failure’.. ch2

My Aunt Accidentally Sent Me A Video Of My Family Calling Me A “Pathetic Failure”.. Part One My name…

End of content

No more pages to load