At my sister’s wedding, I was seated in the hallway—so I left. What happened next shocked everyone.

Part One

I wasn’t expecting a red carpet. I wasn’t expecting a toast, a hug, or my name engraved on a champagne flute. But I didn’t think they’d sit me in the hallway.

Literally the hallway.

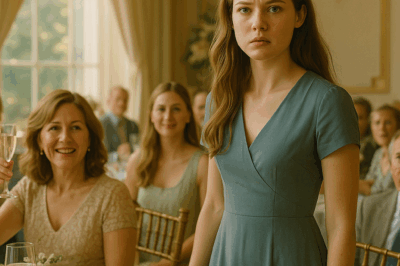

The vineyard estate in Sonoma looked like it had been built for a movie: rolling, emerald rows of vines, ivy climbing old stone, a marble fountain where white peacocks drifted in slow circles like feathered commas. Isabelle always did have a flare for theatrics, and her wedding was the apex—or at least it wanted to be.

A man in a slate-gray vest held open the car door as I stepped out, smoothing the navy silk of the one good dress that still felt like mine. “Rachel Blake?” he asked with a concierge’s smile. “Right this way.”

We passed framed engagement photos of the happy couple—her hand high, the ring catching light, his smile dutiful as a period. At the registration table, a woman with a headset and a tablet had the kind of smile they teach at luxury hotels.

“Your name?”

“Rachel Blake,” I said, steady.

Her smile didn’t falter, but I watched some small muscle jump at the corner of her mouth. She scrolled, paused, nodded too quickly. “Yes, here we are. You’re in the East Alcove.”

“Where is that?”

She pointed down a curved corridor behind the main hall. “Just near the coat check. Very cozy.”

Behind her shoulder, through the arched doors, chandeliers big as small planets bathed the banquet room in gold. The string quartet trilled Vivaldi. My name wasn’t on the big seating chart at all. It was printed on a small card in gold script—East Alcove—as if italicizing it might make it elegant.

“There must be a mistake,” I said, gentle, even.

“This is what we were given,” she replied, and that was that. A wall made of manners.

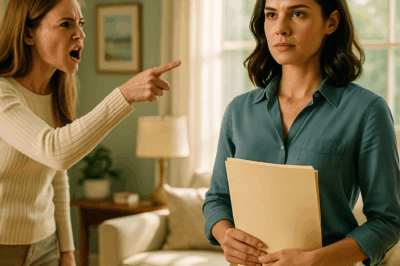

Across the room, my mother stood behind Isabelle, fluffing lace. They looked like a spread in a magazine: mother and daughter framed by light, the veil shimmering, the smile lacquered on. I walked toward them, heels clicking.

“Mom, can I talk to you?”

She didn’t turn fully. “Not now, Rachel. We’re busy.” Busy with perfection. Busy with Isabelle.

“It’ll only take a minute.”

She rolled her eyes and stepped aside half an inch. I told her about the hallway; she didn’t blink.

“We had to prioritize close family,” she said smoothly.

“I am close family.”

A small polished smile. “Don’t make a big deal.”

Isabelle turned then, sweet as frosting. “I’m sure it’s just a mix-up, Rach. Weddings are chaos.” Her eyes sparkled like cut glass.

Something inside me cracked, not loudly but cleanly, the way ice gives underfoot.

“Don’t ruin your sister’s big day,” my mother said softly—soft the way a warning can be. “You should be grateful you were invited.”

Grateful. Like being tolerated was a favor.

I turned and walked to the East Alcove, the word “cozy” hanging in the air like a tacky sign in a cold waiting room. The bench near the coat rack was velvet and maroon and tried very hard. The hallway smelled like lilies and citrus floor polish. Through the closed doors came applause. Isabelle had made her entrance.

I sat there holding my name card. In the glass across from me, a woman I recognized—me—looked back: grown, put together, lipstick precise. And I felt sixteen again, fading at the edge of every frame.

Memory slammed me like a door left ajar in a wind: Thanksgiving, three years ago, Isabelle somewhere in Portugal posting oceans at sunset, the house quiet. My mother asked me to grab a box of photos for “Isabelle’s engagement album.” I went upstairs, pulled open the drawer, and found a thin, leather-bound notebook tucked under a silk scarf. My mother’s angular handwriting filled page after page.

Isabelle didn’t cry her first day of kindergarten. She waved, a little bird ready to fly.

Isabelle loves my salmon. She eats it with her fingers when no one is looking.

Isabelle is afraid of thunder. She tells me she protects her dolls from it.

Pages of Isabelle. Only Isabelle.

When my mother walked in, I was still on the floor. “You wrote all this?” I asked.

“Of course,” she said. “Isabelle was so sensitive. She needed it.”

“And me?”

“You’ve always been independent, Rachel. You didn’t need to be written about.”

It wasn’t anger that came then. It was hollowing, a house settling into its own foundation until it broke.

Now, on a velvet bench beside a coat rack, I traced the edge of my clutch with my thumb and breathed through the embarrassment like a slow bleed. Some people are forgotten by accident. I was forgotten on purpose.

“Rachel.”

Isabelle’s silhouette filled the doorway to the banquet hall—glittering gown, veil floating like a soft threat.

“Are you upset?” she asked, amused.

“Why would I be?”

“Because of the seating. Weddings are chaos; people get misplaced.”

“It’s not the seat,” I said. “It’s what it means.”

She laughed softly. “You’re always so sensitive.”

“Do you ever listen to yourself?”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“That you assume the rest of us are trying to take something from you or ruin your moment. You don’t see the people you don’t step around to be center stage.”

Her smile tightened. “You sound jealous.”

“No,” I said, calm. “I sound tired.”

She leaned in, voice syrupy. “You’ve always wanted to be the victim, Rachel. You wear pain like pearls. It makes people feel sorry for you.”

Something colder than anger lifted my chin. “I never wanted pity,” I said. “I wanted respect.”

“You wanted to be me,” she whispered. Her eyes gleamed.

“It’s not about wanting to be you,” I said. “It’s about not wanting to disappear every time you enter the room.”

Before she could sling another line dressed like concern, a man’s voice cut the air.

“Rachel.”

Julian stood in the corridor, tux perfect, tie loosened just enough to out his nerves. He glanced at his bride, then back at me, and there it was—doubt. Not the performance kind. The real kind.

“Can I talk to you?” he asked.

Isabelle stiffened. “Is something wrong?”

He didn’t answer her. He looked to me, and for reasons I’m still not sure of—maybe because I knew the weather before it broke—I nodded.

We waited until Isabelle floated back into her ballroom. The doors swung shut. The music swallowed her.

Julian exhaled through his nose. “Has she ever said anything…about me? To you?”

The question startled me. “Why?”

“Because lately it’s like she’s wearing me like an accessory when other people can see and tossing me into a drawer when they can’t. She’s…performing. And I’m the prop.”

The last family dinner flashed in my mind: Isabelle calling him “the most manageable man,” the table laughing, me staring at my water. I should’ve said something. Who would’ve believed me?

“I think,” I said carefully, “you might not know who she is when you’re not a camera.”

He swallowed. “I’m starting to realize that.”

He didn’t get to say more. Another woman’s heels approached—measured, elegant. Diane Carter—Julian’s mother—appeared like an injunction: navy gown, platinum hair, the kind of poise earned, not bought.

“A friend at Isabelle’s stylist studio accidentally sent me their backup files when I changed a fitting time,” she said, holding out a phone like evidence. “I didn’t mean to see any of it. But I did.”

Julian scrolled. I watched disbelief shatter into betrayal in slow gradations. His hand trembled.

“She said I’m predictable,” he whispered. “That she can train me. That once she has my trust she’ll control the estate…through me.”

“She also texted,” Diane said, voice crystal, “that six months after the wedding, she’d start the legal process to control joint assets. ‘As long as I stay sweet,’ she wrote, ‘the house will be mine before he realizes it.’”

Julian closed his eyes. When he opened them, something had steeled. “Thank you,” he said to his mother. Then to me, softer: “And you.”

He reached into his jacket and touched the edge of a white envelope. “I need you there,” he said. “Not to fight. Just to not let me lie to myself.”

I nodded.

The conference room upstairs had floor-to-ceiling windows and a view wasted on what was about to happen. Isabelle entered a minute later, our mother shadowing her like a well-trained echo.

“What is this?” Isabelle demanded. “Why are you pulling people out of my wedding?”

Julian slid the envelope onto the table between us. “You know what this is.”

She stared like it might bite. “A prank?”

“A petition to annul,” he said, voice flat. “Signed.”

Margaret—my mother—made a brittle sound that wanted to be a laugh and failed. “Don’t be absurd.”

Diane’s voice cut through. “We saw the messages, Isabelle. You didn’t leave much to context.”

“I was venting with friends,” Isabelle hissed. “You’re all being dramatic.”

“And the divorce consultation with a ‘property optimization plan’ dated last month?” Diane asked. “Was that venting too?”

Even our father, who had wandered in during the storm, looked staggered. “Is that true?” he asked Margaret, not Isabelle. Old habits.

“I didn’t know,” my mother said quickly. It was the first honest thing she’d said all night. “I—”

“You never wanted to,” our father said quietly. Then—to me, as if noticing I was in the room for the first time in fifteen years—“Rachel, I should’ve said something years ago.”

“I wasn’t okay,” I said. “But I am now.”

Isabelle’s composure snapped like spun sugar meeting rain. “You’re siding with her,” she spat, eyes like cut glass. “You’ve always resented me, Rachel. You came here hoping—”

“I came to be your sister,” I said. “You never once treated me like one.”

She looked from me to Julian to Diane and back. Fear finally found her face, not because she was caught but because the choreography had failed and no one knew the next step.

She didn’t storm so much as detonate out of the room. When she hit the ballroom, the quartet faltered. Hundreds of heads turned in the same instant.

“You think this is funny?” Isabelle shouted into the chandeliers. “Humiliating me on my wedding day?”

“No one humiliated you,” Julian said from the doorway. His voice carried further than it had any right to. “You did that yourself.”

“You said you loved me.”

“I did,” he said. “Until I realized you never loved me.”

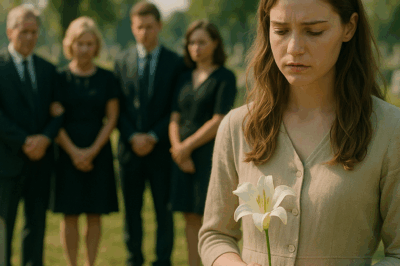

The room held its breath. Diane touched her son’s arm. “Let’s go.”

Isabelle reached out, but no one reached back. Not her friends, not her bridesmaids, not the parents who had taught her the world was a stage and her name the only credit that mattered.

Julian lifted the white envelope so the room could see it. “This is the annulment,” he said. “Signed.”

The gasp felt like a weather pattern. Isabelle ran. The doors swung shut behind her. The quartet set down their bows.

I remained in the threshold, not triumphant, just standing in a space I hadn’t been allowed for years. For once, my presence wasn’t an inconvenience or a prop. It was a witness.

Part Two

I woke a week later in my small Boston apartment to the soft hum of a refrigerator and the slow travel of morning across my wall. No chandeliers. No headsets. No seating chart. No hallway. Just a growing square of light and the sound of my own breathing.

My mother had called every day since Sonoma. I let the calls stack up into a silent tower. The texts began softer than I expected.

Rachel, I know I failed you. I know I was blind. Please. Just coffee, just us.

A year ago, I would have said yes before the message finished loading. I would have chosen a blouse she liked, rehearsed polite sentences, braced for the conversation to slide back to Isabelle. I would have smiled until my mouth hurt. Then I would have gone home and stared at the ceiling until morning.

I put the phone facedown and walked to the river instead. The lamps along the Charles were still on, their light ribboning across the water. I sat on a bench and unfolded an old photo—Christmas, the red dress, the hand on the shoulder that wasn’t mine. I folded it neatly and slid it back into my wallet. I didn’t need to tear it. I just didn’t need it anymore.

Back in my apartment, I took the cracked-spine album from my shelf and slid it into a storage box. Closures don’t always require flames. Sometimes they just require a closet.

That afternoon I booked a cabin in Maine. Just me, a stack of books, a window to a cold blue. I didn’t text anyone the dates. I didn’t ask permission. The confirmation email chimed. It felt like a bell rung in a church I hadn’t believed in for a long time.

The messages from Sonoma continued, not just from my mother but from guests—apologies wrapped in gossip, gossip wrapped in apologies. I answered none of them. Then a voicemail from my father, halting and shy in a way I’d never heard from him.

“I’m sorry, kid,” he said. “For the…everything.” He chuckled softly. “Your mother and I are…learning.” I let him have his ellipses. Some men experience vocabulary late in life.

A month after the wedding that wasn’t, I received a square envelope with thick paper. Diane’s handwriting on the front. Inside, a note:

You were anchored when my son needed bedrock. When you’re in Boston next, I’d like to buy you a coffee that tastes like something and ask about that quiet you carry so well. Respectfully, Diane.

I laughed at “tastes like something” and folded the card in half carefully, a small origami of respect.

Isabelle reappeared online as if nothing had happened—sun-drenched brunches, pilates, a caption about resilience with a sparkly heart. Her friends liked it. I did not. She reached out once with a single line—You ruined everything. I typed and erased three responses. Then I chose not to reply at all. No response is not silence. Sometimes it is a boundary that doesn’t want to fight.

The holidays arrived like a test you know all the answers to now. My mother texted that she was making lemon squares “if you still want the recipe.” I didn’t respond. A week later, a card appeared with the recipe in my grandmother’s looping script and a post-it in my mother’s hand: Consider this a first step. I don’t know how to do this. I want to try.

I invited her for tea at a café where the chairs wobble just enough to make everyone pay attention to their weight. She arrived tight in the face, softer in the eyes. We didn’t talk about the journal. I didn’t ask her why my name had never appeared in blue ink. She didn’t ask me to forgive anything or pretend it could be undone.

“I measured love too loudly,” she said, stirring her tea with unnecessary precision. “I mistook volume for care.”

“I learned to whisper,” I said.

We sat with that. It was a start. It was also enough.

On a raw Saturday in March, I took the early bus to the coast and unlocked the cabin. The windows looked like eyes after a cry. The books waited. So did a small yellow legal pad. I wrote the first line of something that might become a memoir or might just be a letter to the kid I used to be: You will want to disappear. Don’t. Just move your seat.

When I returned to Boston two weeks later, there was a voicemail from Isabelle. Her voice was different—not softer, exactly, but less lacquered.

“I thought love was a scarcity game,” she said. “I thought there was only room for one sun.” A beat, then: “I was cruel because I was afraid. You don’t have to say anything. I just didn’t want the next sentence I wrote about myself to be a lie.”

I didn’t call her back. But a month later, when she texted that she’d started therapy and wanted to send me the cover of the journal she was keeping—blank, thick, waiting—I sent a thumbs up. It was the only emoji that didn’t feel like a costume.

I saw Julian and Diane once in Boston, mother and son in coats that looked like competence. We had coffee that tasted like something. Julian laughed easily for the first time since the corridor, then looked out the window and said, “I keep being grateful I found out in time to rewrite the ending.” Diane’s hand—bright with rings, beautiful with age—rested over mine for a moment. “Thank you for not letting us pretend,” she said.

The Maine cabin became habit. So did saying no without sending a follow-up text explaining why no was the vote for everyone’s greater good. I started teaching a workshop once a month for women who sit in hallways like they were told to and then realize they can stand. The class was called Seat Yourself. We did not practice speeches. We practiced exits.

On the anniversary of the wedding that wasn’t, I put on the navy silk dress I’d worn to Sonoma and stood in my kitchen with my bare feet on the tile. The dress hung differently now. I did too. I baked lemon squares using the recipe in my grandmother’s looping hand. I brought a plate downstairs to the neighbor who plays Miles Davis after midnight and a plate to the woman who lives alone with plants she keeps alive out of sheer will.

I sent a photo of the squares to my mother. She texted back three words I didn’t expect: Come by Sunday. I went. The kitchen looked the same: bowl of fruit as centerpiece, calendar with appointments and a script of the month’s meals. She pulled a leather-bound notebook from the drawer. We both stared at it.

“I thought about burning it,” she said. “But I want to add.”

“To what?” I asked.

“To the record,” she said, looking at me the way people look when they decide to focus. She uncapped a blue pen—the blue I knew from childhood—and wrote, in deliberate, careful letters, “Rachel moved to Boston and learned to be visible. She makes the best lemon squares now.” Then she laughed, tiny and real. “Not as good as mine.”

“They’re different,” I said. “Both good.”

We didn’t hug. We didn’t fix anything. We made tea.

If you ask me now what shocked everyone that night in Sonoma, it wasn’t the annulment. It wasn’t the envelope or the phone with its little glowing betrayals. It was smaller and louder than that. It was the sound of a woman in a hallway deciding to stand, and then standing. It was the sound of other people hearing her weight shift and realizing the floor isn’t immutable.

The next time someone prints a seating chart with your name in italics by a coat rack, move your chair. Or don’t sit at all. Walk into whatever room the door opens on, not because you need the chandeliers to validate your outfit, but because your presence is not a favor. It’s a fact.

A year after Sonoma, I hosted a dinner in my apartment. Not a spectacle. Six chairs, one table, soft jazz, bad jokes. My father told a story with an ending this time. My mother ate slow, which for her is a confession. Diane mailed a bottle of something and a note: For the woman who didn’t scream and still made the room listen. Isabelle sent flowers with a card that said only, “Thank you for not letting me win.”

I stood at the sink that night, hands in warm water, the smell of citrus and sugar on the air, and thought of the hallway. Of the way the light hit the maroon velvet. Of the little gold card with my name. And I smiled, not because I was chosen at last, but because I had chosen myself.

END!

News

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… CH2

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… Part One I…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited me Over Just to Tell me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited Me Over Just to Tell Me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her …

At My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. CH2

My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. Part One…

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And then.. CH2

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And…

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a… CH2

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a … Part…

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration. CH2

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load