My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars..

Part One

I didn’t recognize the sound of my own pulse until the room went quiet.

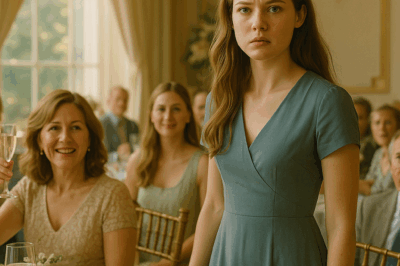

One minute the Harbor View restaurant was a cathedral of clinking glasses and high laughter, magnolias spilling down the center of the long table like someone had taught flowers to pose, Megan’s diamond working every angle for the cameras. The next minute, my father was pulling a thick white envelope from the inside of his blazer and saying, “A marriage needs a home,” the way a man says amen when he’s halfway through a prayer he’s recited his whole life.

When Megan opened the envelope and slid out a rectangle of paper as if she were unveiling a painting, I already knew which house would be printed there. I knew it because I had scrubbed the Charleston humidity from every corner of it, because the laminate flooring in the living room still held one faint nick from the day I’d dropped a box of plates and left a whisper of a scar, because the patio out back had a hairline crack that only I knew how to find if the sun hit it wrong.

“The Bay Street house,” Dad said, and there it was, the deed, crisp and smug in my sister’s hands. “Fully paid, in both your names.”

I don’t remember setting my glass down. I remember the phoniness of the applause, the way it swelled like a tide that doesn’t care what it takes with it. I remember the look on Patrick’s parents’ faces—quiet approval polished by decades of being people who expect to be pleased. I remember the weight of my rent receipts in my purse and the photo gallery on my phone full of before-and-afters: the dingy carpet I ripped up with blistered fingers; the bathroom tile I learned to lay by watching videos at midnight; the porch ledger board I set level despite the slur of August heat.

It had been Dad’s idea. Three years earlier, sitting at our usual corner table at a coffee shop on King Street, he’d stirred sugar into his coffee and not looked me in the eye. “You’ve been steady,” he said finally, meaning unlike your sister without saying it. “That place on Bay, the two-story I picked up last year—put in fifty, keep up with rent, show me you can handle it. In a few years, I’ll sign it over. Equity instead of just rent down a drain.”

As a financial analyst, I tell people every day to put promises on paper. But this was my father, and that old ache—the one that started when he put a pizza party on the calendar because Megan got a B in history and couldn’t be bothered to notice when I won regionals in science—swelled into hope. We wrote the terms on two pages from the legal pad he kept in the truck: $50,000 as investment toward ownership, rent on time every month, house kept up to standard. He signed. I signed. We didn’t take it to a notary because family is supposed to be a notary for your heart.

I pulled every dollar out of the account I’d fed since my first internship. Fifty thousand slid from my life into a promise I believed in hard enough to breathe. I paid $1,800 every month thereafter, never once late. I spent my Saturdays at Lowe’s and my Sundays on the floor with a level, learning the language of walls. I installed smart lighting that made the rooms glow instead of squint. I built a patio with my own hands and a borrowed wheelbarrow because no one else was going to build me a place to drink coffee in the morning and pretend the world was understandable.

It wasn’t just sweat. It was math. The house appraised at $350,000. Even with the upgrades and the rent, I was building equity for the price of competency and calluses. The plan had heft. It held.

What I didn’t account for, what I never really have, was the gravity of Dad’s orbit around my sister.

Growing up in our Charleston house was an education in impurities. Mom—soft voice, sharp mind, paint in her hair from the art classes she taught at the community college—was the buffer who noticed the invisible. She noticed that I liked my books stacked spines out by color. She noticed when Dad missed another one of my swim meets because Megan had a recital at the same time and “Angela’s on the team; she’ll swim again next week.” Mom would pull me aside and say, “Keep going. Your spark is bright,” as if sparks could burn through plaques that had other names scratched into them. Ovarian cancer took her when I was thirteen, and the house lost its busiest quiet. Dad started talking about Megan in declaratives—“my girl,” “my star”—and I learned to breathe around a voice that said my name only when it needed something.

By the time I was twenty-eight, that pattern felt as permanent as the marsh out past the porch steps. Megan flamed through two community colleges, opened and closed a boutique like a curtain, and came out the other side with Dad still paying her car insurance. I graduated early, took a job that had me speaking three languages at once (spreadsheets, client, ego), and paid for my own tires. When Dad slid that envelope across the dinner table with “Bay Street” and “equity” and a timeline you could see from the right angle, I believed him. I wanted to. The part of me that wanted him to hold out a ribbon at the end of my science fair lap and look proud enough for two parents grabbed that promise with both hands.

And then Megan met Patrick.

He was decent, which I didn’t know how to hold against him. State university, good shoulders, the kind of laugh that gets you invited to everything. His father owned a shipping company out of Savannah that insisted on being called a “firm”; his mother was a lawyer who had perfected sympathetic eyebrows. When they announced the engagement at one of our awkward family dinners—me eating quietly so Dad could hear himself celebrating—Dad stood up so fast he knocked his water over and said, “Let’s do this right.”

I coordinated the dinner because Dad demanded it and because I understand how to turn chaos into an event where everyone thinks they’re happy. I wrangled magnolia centerpieces and crab cakes and a string quartet that could play “At Last” and “Yellow” without sneering. Patrick and I ended up side by side at the tasting choosing between two kinds of risotto while Megan “couldn’t get out of work” again. “I never had a sibling,” he admitted, eyes kind, and I swallowed my bitter with a smile.

Two days before the dinner, I dropped by Dad’s house with the seating chart and heard voices in his study. “Once we’re married we need space,” Megan was saying, her tone the version of a command that expects applause. “Patrick’s condo is fine, but it’s cramped. My place is… falling apart.”

Dad laughed, warm enough to make me feel like a stranger. “I’ve got something in mind. Think of it as an engagement surprise.”

I stood in the hallway staring at a framed picture of Mom mid-laugh and told myself he couldn’t mean my house. Dad had other properties: a duplex by the greenway, a cute bungalow with porches that needed love. He had promised me Bay Street. He had signed. He had meant it. He had to have meant it.

At the dinner I learned what we already know: promises are lighter than paper when the person who made them wants to be admired.

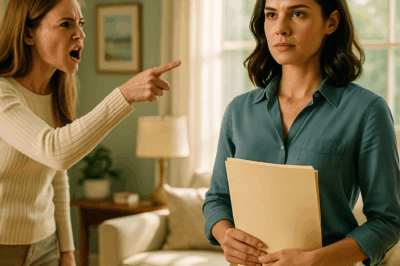

After Dad said “a marriage needs a home” and the room rose around him like a tent to keep the rain off the chosen, after Megan pressed her cheek to his shoulder with that performative gentleness she keeps for cameras, after Patrick’s mother said “Juan, how generous” in a voice that makes the word sound like ownership, my father looked at me with a face that slid from fond to flint and said, “Angela, you’ll need to be out by the end of the month. They’ll want to settle in before the wedding.”

My body turned to something like stone and something like air. I walked to the bar because my legs wanted to move. “That is my house,” I said when Dad came to adjust his tie in the mirror. “We had a deal. I put fifty in. I paid rent. I did the work.” He looked at my reflection instead of my face. “Don’t make a scene,” he said. “This is about family. Your sister needs a start.”

You’re good with money, he didn’t say out loud. You’ll figure it out. He did say: “Be supportive.”

Patrick caught my eye as I turned back to the room. His smile faltered. I think he saw me. I think he didn’t know what to do with the seeing. Megan didn’t look at me at all. She waved the deed like a flag and told Patrick’s mother she was thinking open plan for the kitchen, and if I had been holding a glass it would have shattered from the inside.

When I got home to the house that was still mine for exactly twenty-six nights, I walked through every room and laid my hand on the things my labor had turned into grace. The motion lights I wired in the hallway that made the dark tilt toward welcome instead of fear. The couch I bought used and made good with a rug underneath that did the heavy lifting of color. The stainless steel fridge I’d negotiated down to a price that made the delivery guys roll their eyes. The patio—oh, the patio—with the line of potted rosemary and the chair that fit the back of my body like a handshake.

I made a list. It wasn’t a revenge list. It was triage. A life can bleed out from a hundred small arteries. Stop this one. Clamp that.

I called Denise.

We’d been friends since the year textbooks weighed more than our choices. The kind of friend who shows up with a lap and a list when you say you’re not okay. She was also a lawyer who liked property disputes the way I like spreadsheets: not because they’re fun but because getting to the bottom of them is satisfying in a way that feels like truth. She arrived at noon with her laptop and an expression that belongs in an icon painting. “Tell me everything,” she said. I did.

“He can’t do that,” she said finally, tapping the agreement’s thin paper with a pen that could have been a baton. “It’s basic, but it’s a contract. You invested. You performed. He promised consideration. And you have receipts: the fifty, the rent, the improvements. Before we go to court, we send a demand: the deed as agreed, or restitution—fifty plus the value of your upgrades. In the meantime, take your stuff.”

“Take my… stuff?” I said, looking around at the house that had been built with sweat and the kind of stubbornness that grows under your fingernails.

“Furniture. Appliances. Lighting—if you can swap without damage and reinstall what you replaced. Anything you installed that isn’t permanently affixed is yours. You leave it safe. You don’t leave them with the fruits of your labor if they didn’t pay for the tree.”

I rented a storage unit with a garage door that hummed like a song. I called Mark from work and Sarah from book club. I hired a handyman from Folly Road who knew how to shut off water lines without baptizing the kitchen. I dug out the old ceiling fans from the crawlspace and the original dishwasher from the shed out back that Dad had called “inventory” and I had called “future problems” and I made them ready. If there is one thing a childhood like mine gives you, it is the ability to work like your life depends on getting two things done at the same time.

On Friday night I unscrewed the smart bulbs and replaced them with bulbs that were merely lights. The hallway got dimmer. My resolve didn’t. On Saturday we moved the couch, the bookcases, the bed. We unscrewed the patio string lights and shook the dust off them like old songs. The fridge required gloved hands and patience; the old one went back into its space with a sigh that said I knew you’d want me again. In the bathroom I took down the mirror I had chosen and put the old one back, the one with the chip in the corner that had taught me not to look in the wrong place to find myself.

Every time my muscles protested, I whispered the number in my head: fifty. Sixty-five in rent times thirty-six. Twenty into tile and laminate and switches. One hundred and thirty-five thousand dollars of work, of love, of math. I photographed every room before and after in case anyone wanted to argue about intent with a judge who’d seen too much of that in divorce court.

On Sunday, right before dark, Mark stood in the kitchen and whistled at the version of the house that had returned. “Brutal,” he said, almost admiring. “They’ll think you’re a monster.”

“They already do,” I said. “This is for me.”

Megan texted at noon. We’re going by the house! Any tips on the layout? I wrote: You’ll see. Patrick texted an hour later: Angela, I didn’t know about your deal. Can we talk? I put my phone face down on a box of plates and kept moving.

Dad and Megan showed up at my rental the next day with Patrick trailing behind them like a conscience. I opened the door and stood in the frame. I didn’t invite them in. “You gutted the house,” Dad said, marveling, as if he’d stumbled onto a ruin. “The appliances, the fixtures—everything gone.”

“I took what I paid for,” I said. “I put everything back that was there when I moved in. It’s safe. It’s legal. It’s fair.”

“That’s our home now,” Megan said, and if incredulity could be a laugh, hers was. “You’re being—”

“Efficient?” I offered. “Prepared? Tired of being invisible?”

Patrick looked at me and then at the ground. He is not my problem, I reminded myself. He will never be the problem I prioritize. “I didn’t know,” he said, and I believed him because the surprise in his voice had the shock of a decent man’s first lesson in someone else’s family history. He turned to Megan. “Why didn’t you tell me she paid for it?”

“Because Dad said it was his to give,” she said. “Because it was.”

“Because promises don’t apply to me,” I said, and Dad finally flinched.

“Don’t make this ugly,” he said.

“You already did,” I said. “Denise sent you a letter. We’ll settle or we’ll sue. Your choice.”

The settlement came three days later. They offered fifty plus fifteen for improvements. Denise countered twenty-five for the upgrades because she knows that a person who invested dignity has to overprice just enough to make dignity visible to people who otherwise wouldn’t value it. They accepted. The money hit my account with a thunk that didn’t make me feel rich and didn’t make me feel poor. It made me feel free.

I bought a condo on a quiet street where the marsh is a rumor at the end of the block and the light is good in the morning. I hung my art. I reinstalled the smart bulbs. I put Dad’s letter in a frame and Mom’s magnolia print over the couch. The first evening I sat on the tiny balcony with a glass of wine and watched the wind move across a tree and thought, I did that. I saved me.

My father texted once: Coffee? We should clear the air. I didn’t respond. My sister texted: I didn’t mean for it to be like this. I let the message blur and then vanish. Patrick sent a note with no ask in it: I’m sorry. I hope you’re okay. I put the phone down and went to bed.

At work, my boss put a hand on the back of my chair during my review and said, “Something’s changed.” I argued with a client about ridiculous assumptions and won by saying, “No,” like a person who had practiced it at home. Denise came over with Thai food and we ate on my floor like we used to and she said, “You can breathe,” and I said, “I can.” A man named Daniel who lives two doors down asked if I was the person who put rosemary on every windowsill and I said, “Guilty,” and he asked if I wanted coffee sometime and I said, “Yes,” and then I said, “But a good one,” and we laughed because sometimes lives change in ways that feel less like plot twists and more like relief.

Megan sent an invitation to the wedding. I wrote a card with a neutral wish and mailed it. I didn’t go. A cousin told me they’d spent a small fortune redoing the Bay Street kitchen anyway. “Open plan,” she said, and I said, “Of course,” and then we talked about her kid’s soccer team because I am done discussing houses that no longer contain my life.

On a Sunday afternoon I took my coffee to White Point Garden and watched strangers’ dogs pretend to understand history. I thought about Mom telling me my spark was bright. I thought about who I became without needing anyone else to reflect light onto me to make it real.

It seems too neat to end with a lesson, but I keep finding this one and it keeps fitting: the moment you stop asking someone to see you and decide to be visible to yourself is the moment you stop bargaining for your worth. Family can be the people who sign their names under promises they keep. Sometimes they are not. In either case, you get to decide what becomes yours.

I paid fifty thousand dollars for a house and three years of my best weekends for a dream. It was not a waste. It bought me a spine and a door I can lock. It bought me the kind of quiet where you can hear yourself think: I matter. It bought me the knowledge that if someone ever tries to hand your life to someone else as a gift, you can take a deep breath, pick up your toolbox, and begin again.

Part Two

Charleston’s light is loud in the morning. It poured across my new kitchen and turned the coffee in my mug into something like a mirror. It made the papers on my counter—closing statement, demand letter, second copies of receipts in case anyone decided to be forgetful—a still life of resolve. I sat there and let the brightness work on me the way sun does on damp walls after a storm: steady, inevitable.

The calls slowed. The texts shrank. The air between me and my father went from charged to static to something else: blank. It’s a strange grief, losing a parent while they’re still alive. It’s quieter. It jumps out at you in the grocery store when you see the right kind of cereal box. It shows up when you do something good and your first instinct is to call someone who taught you how to want their approval more than you wanted your own. My therapist, a woman who wears clogs and mercy, said, “You can grieve the father you didn’t get without pretending the one you did get loved you wrong in every way.” It helped. I wish it didn’t.

I made a rule: I would not talk about the house unless I had to help someone else stand up. I broke it twice and forgive myself once a week for being human. A colleague with a father who had started saying “equity” with too many syllables took me to lunch and asked, “How did you know it was time to stop being the easy daughter?” I said, “When being easy felt like making myself smaller every day and calling smallness kindness.” She cried at the table. The server gave us extra napkins and a cookie and we both laughed.

It would be tidy to say Patrick and Megan lived happily or that they didn’t. The truth is less symmetrical. They threw a wedding that looked like a mood board. She wore a dress with sleeves like a sentence that needed more punctuation. Patrick’s mother tried to put her hand on mine at a market once and I moved before she could because boundaries are easier when your body remembers to keep them. A mutual friend said Patrick insisted they send me a thank you for handling it, like the house had been a package delivered by someone with a uniform. I was glad to hear he was learning to require fairness. I did not require his updates.

At the foundation, Juan’s Fund printed its first pamphlet—ugly the first time because we used a template; better the second after I redesigned it on my couch between episodes of a show about people who rebuild kitchens without checking the joists. We handed out three stipends in the fall. One kid put his toward a welding certificate, one toward HVAC, one toward a semester that didn’t make him cry about money on the phone with his mother. I went to the ceremony and cried at a podium because I am allowed to. Dad would have hated the speech and loved the tools we rolled out of storage.

“Come by the shop,” one of the kids said later, proud as a table leg. “I’ll fix your AC for free.”

“No,” I said. “You’ll charge me like a professional. Then I’ll recommend you like a person whose name belongs on the back of the fridge.”

Daniel came over with basil seedlings and humility. We cooked together because lovemaking is built in kitchens long before it becomes anything else. He is the sort of man who asks, “Can I hang this for you?” and then learns how to spackle because he doesn’t want to leave holes when he goes. The first time I told him the whole story, he said, “You didn’t get smaller to make them big,” and I felt the kind of love that makes you look at your own reflection with less suspicion.

The settlement covered the condo and six months of cushion. After that my work and my sense of my work covered the rest. My boss handed me a portfolio that had always gone to someone with louder opinions and watched me tip the room toward the right decisions by refusing to be interrupted. “It’s wild,” she said at my next review. “You’re the same and different.”

“I made a choice,” I said.

“You started telling the truth out loud,” she corrected. “We needed that.”

The truth did what truth does when you let it stack up: it freed space for other things. I painted the hallway. I joined a running group that met at White Point and made the bridge sturdier under our feet. I stopped checking to see if I fit into old dresses and started noticing I could lift boxes without holding my breath.

On the anniversary of Mom’s death, I made her shrimp and grits recipe the way she taught me—extra butter, don’t skimp on the pepper, let the onions get almost too soft. I put her magnolia print above the stove and told her I’d built a life where nobody gets to give away what I worked for. If she answered, it was in that way dead people do: a sigh that could be the AC reading the room or a feeling that the house understood.

A month later, a letter from Dad arrived in my mailbox, handwriting stubborn. Coffee? it said. We should clear the air. Love, Dad. I put it under a magnet and went about my day. A week later I took it down and put it in a folder labeled Not Now. I may throw it away. I may not. Boundaries can be acts of love if you name them that way.

Megan sent a postcard, not from Las Vegas or Paris but from Sullivan’s Island, which felt like progress. On the back she wrote, I’m getting better at standing up to him, and drew a lopsided heart. I taped it next to the Las Cruces card. Because hope is a habit and I want mine to stay in practice even if it never gets another chance to be rewarded.

Aunt Joan told me at a barbecue—the kind where men pretend to tend the grill while women do the thing that makes the day happen—that cousins have started saying my name with something like respect when they tell the story. “They say you did right,” she said between bites. “They say he did you wrong. They say she didn’t know better. They say you made it so she has to learn.”

“I didn’t set out to teach anybody anything,” I said. “I set out not to let them steal my life.”

“It’s the same lesson,” she said, and wiped her mouth with the back of her hand like a woman who knows nothing good was ever born out of being delicate.

When people ask me now what I bought with fifty thousand dollars, I tell them: a way of holding myself that will not collapse under the next person’s generosity. I bought a lesson I didn’t know I would need this much: that you cannot build your life out of other people’s promises and then be shocked when a strong wind knocks it apart. You have to build with joists and glue and nails you drive with your own arm. You have to be the one who checks if the wall is load-bearing and then decide whether to knock it down anyway.

On a Thursday night in November, after the first real cold front came down the coast and told Charleston to remember what seasons are for, Daniel and I sat on my balcony under a blanket and listened to the city. “To new beginnings,” he said, lifting his glass.

“To the courage to keep going after the last one ended,” I said, clinking mine against his, feeling this new chapter settle into place like a board flush against a beam. Solid. Real.

If someone ever hands your life to someone else as an act of love, you are allowed to say no. You are allowed to take your bulbs and your fridge and your good chair. You are allowed to get a lawyer. You are allowed to tell a room full of people who have always been clapping for the wrong thing that applause is not law. You are allowed to walk away and refuse to look back until there is something on the horizon you chose.

The night Dad gave my sister my house, I thought he had taken everything. He hadn’t. He’d given me a chance to show myself who I was when nobody important was watching. Now when I stand in my doorway and lock it, I do not think mine because of paper. I think mine because my life fits inside it and finally, beautifully, so do I.

END!

News

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… CH2

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… Part One I…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited me Over Just to Tell me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited Me Over Just to Tell Me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her …

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And then.. CH2

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And…

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a… CH2

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a … Part…

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration. CH2

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration Part One…

At My Sister’s Wedding, Her Husband Smashed the Wedding Cake Into My Face, But then… CH2

At My Sister’s Wedding, Her Husband Smashed the Wedding Cake Into My Face, But then… Part One My name…

End of content

No more pages to load