At My Retirement Party, My Daughter In Law Slipped Something In My Drink — So I Switch Glasses.

Part One

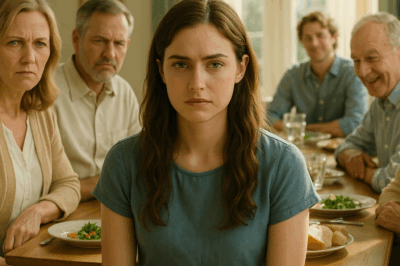

The champagne caught the chandelier light and broke it into a thousand glittering knives—beautiful, useless, and everywhere at once. “To Sarah,” someone said, and a wave of polite cheering rolled through my marble kitchen. They were all there for the show: the neighbors who’d watched me leave for work at dawn for thirty years, ex-partners who’d sworn they’d outlast me and hadn’t, my son Michael, and his ever-hungry wife, Jessica.

I sell people certainty for a living. I can smell it when it goes sour.

She was near the bar—of course she was—with her shoulder turned just enough to make her purse a small, private stage. A tiny brown vial rose from the handbag, tilted, and whispered its contents into a flute with a hairline chip on the rim. My glass. My party. My death.

I didn’t gasp. I’d spent too many years in rooms where the first gasp loses. Instead, I smiled at the Vice President of Nothing Who Once Told Me I Was “Surprisingly Sharp,” thanked him for his compliment about my “still formidable energy,” and drifted toward my future murderess.

“Sarah, you look tired,” Jessica said in that tone rich women use when they’re discussing takeout. Her manicure clicked against the flute. “Here, have some champagne. You’ve earned it.”

“Well, if you insist,” I said, and took it. I let the bubbles wink at me, let her see me lift the glass, and then waited for the room to turn its head for the cake.

When it did, I set my flute next to Helen’s purse.

Helen is Jessica’s mother, all kind eyes and lost keys; she had followed the cheese tray like a ship follows a lighthouse. She smiled at me with the vague sweetness of people who have never had to read fine print. Her hand found the nearest glass—the chipped one—and she said, “Oh, this tastes…interesting. Where did you get it?”

Two minutes later she was on my floor, the flute broken beside her, foam blooming at the corners of her mouth like sea scum.

If you have never seen a plan fail in public, you have never lived.

“Call 911!” Jessica screamed, accessing a grief that would have been Oscar-worthy if it hadn’t been rehearsed. She keened at the right volume and clutched my sleeve in precisely the way a daughter-in-law clutches an inheritance. Michael—my boy who’d once trailed buttered toast through my kitchen like breadcrumbs—looked stricken, and underneath the pallor, alert. He scanned the room, then Jessica, then me, then the flute—calculating.

Which hospital? I asked the paramedic while Jessica sobbed something about “Mom, stay with me.” St. Mary’s, he said. Family only. “Close friend,” I said without looking at Jessica, and followed the gurney out.

At St. Mary’s, fluorescent lights erase the difference between saints and sinners. While the doctors worked on Helen, while the nurses said “acute poisoning” and “plant alkaloids” to each other in the tone librarians use for gossip, I watched my children.

Jessica paced holes into the lenoleum, her heels counting out anxiety in a staccato that betrayed practice rather than panic. Michael sat rigid in a chair, his phone buzzing like a trapped wasp in his pocket, his thumb hovering and hovering and hovering.

“Terrible,” Jessica said for the fifth time. “Just terrible.” She wrung her hands and looked at me as if I might absolve her. “What do you think it was? Food? The champagne?”

“Lucky she didn’t drink much,” I said. “Only a few sips. Clever woman, Helen.”

Jessica’s breath caught. “Champagne?” she repeated too quickly, and then forced a laugh. “Doctors said not food poisoning. Probably her meds. You know Mom—careless.”

I do know Helen. And she counts pills like diamonds.

Three hours later, a doctor told us Helen would live, sedated and embarrassed. “We’ll keep her overnight,” he said. “Something toxic, but we can’t pin it down.” He said “toxic” like it was a crossword clue. Jessica pressed a hand to her forehead and nodded.

Michael walked me to my car. “You should stay with us tonight,” he said—casual, practiced. “After…all this.”

The thoughtful wolf at the grandmother’s door. Red Riding Hood has better lawyers now.

“Sweet of you, dear,” I said. “I have a security system.” I kissed his cheek, slid into my car, and drove home through the oldest part of my city, looking at the houses where people keep secrets behind good hedges.

I poured myself a clean drink from a clean bottle and took my legal pad to the kitchen table. I don’t do “confused” and I don’t do “why me.” I do inventory. Gifts over five years labeled “help” instead of “loan”—nearly two hundred thousand. House down payment for a house too big and bright to be paid for by Michael’s faltering architectural firm and Jessica’s jewelry hobby—my check on that one had been thick, heavy, generous. Private school tuition for Emma because “public schools aren’t safe anymore,” as if safety were something you can buy in an admissions office. The BMW and the Mercedes and the granite and the glass—all mine, just laundered through their taste. I had built a life with a man who died fifteen years ago. I had an heir and his wife who could not wait for mine to end.

At 7:30 the next morning, the phone rang. “Sarah,” Jessica cooed, “how are you feeling? I didn’t sleep at all, thinking…if there was something at the party…”

“Nothing here gave anyone convulsions,” I said. “You must be relieved Helen will be fine.”

“So relieved,” she said with the particular flatness of someone reading cue cards.

At nine, Michael arrived with pastries from my favorite bakery. He opened my cupboards without asking and set the coffee like a son. He sat like a stranger. “Mom,” he said, “this house is too big for you. It’s time to think about safety.”

I let him show me the Sunset Manor website: hydrangeas, “fitness classes,” elderly people smiling at puzzles. “Lovely,” I said, and kept my face.

He slid a power of attorney form across my table, the kind that gives a child your life in black ink. He explained it as if I hadn’t written my own for Frank’s heart surgery. “Just in case,” he said. “It’s good to plan for emergencies.”

I smiled. “I absolutely agree,” I said, and dialed my attorney.

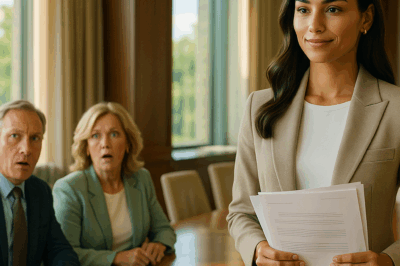

David Hartwell has a face like an expensive shoe: polished, reliable, made to survive a thousand scuffs. He listened to my story in his paneled office, made a few notes, and said, “Good. Let’s make their confidence expensive.”

In two hours I did what men like to pretend women can’t: revoked every authority I’d ever granted anyone, moved six hundred thirty-seven thousand dollars into a bank my son didn’t know existed, rewrote a will, formed a trust with teeth, and installed David as the only person who could sign anything more permanent than a Mother’s Day card on my behalf. “And the house money?” I said.

“It’s messy,” he said. “No promissory note, no recorded lien. But you have emails where they promised to provide you a home in exchange for the cash. We can argue a conditional gift. They failed their condition. We will ask for restitution. With interest.”

“Good,” I said. “Make it compound.”

We added a medical directive that said “no” in every place I could imagine my son trying to say yes for me. “Dr. Steinberg?” I said, when my PI friend Patricia called with her background packet and the name of a geriatric psychiatrist who had been on Michael’s Venmo for three months.

“Accommodating,” David said. “A man whose diagnoses have a way of matching the payer’s preferences.”

“I prefer ‘competent,’” I said, and he scheduled a real evaluation with a doctor who asked me what I’d had for breakfast and then asked me to do math in my head until we were both bored.

By two o’clock, a security company had turned my house into a small fortress with discreet cameras and a panic button on the underside of my desk where my left hand rests when I pretend to be patient.

At three, Patricia delivered the kind of report that used to arrive on my desk with a ribbon. “Two mortgages, a tapped-out HELOC, $80,000 in credit card debt, business bleeding cash for two years, BMW in arrears, life insurance policy taken out on you six months ago with Jessica as the beneficiary.”

I poured myself an espresso and said, “Of course.”

“And payments to a Dr. Richard Steinberg,” she added. “Consultations start three months ago.”

“Of course,” I said again. You don’t live as long as I have without recognizing choreography.

I called Michael. “Lunch?” I said. “Giovani’s? Your father loved the cannelloni.”

He arrived with his hopeful face on. I ordered zucchini fritti and let him watch me play with it until he asked, “Have you decided?”

“I have,” I said. “Sunset Manor looks idyllic. Perhaps we could go see it. They have an opening that requires the entrance fee by Friday.” His eyes lit. “And the power of attorney,” I added, setting my signed document between us like a treat.

He reached. I slid it closer.

“What could go wrong?” I said, and it was almost kind.

They came to my house the next morning to “help with the paperwork.” Jessica opened her laptop like a dealer opening a deck. “Assets?” she asked. “Account numbers? Passwords?”

We filled in the lines. I answered with numbers and smiled with my eyes. When we finished, I asked them to wait—“David’s coming with a few tax forms”—and the doorbell rang.

Detective Lisa Morrison stood on my porch with a partner and a small notepad. The hospital lab had done what labs do: they’d found oleander in Helen’s blood and in my party champagne. “It’s a common ornamental in this county,” the detective said, “and a very old poison.”

Jessica’s face did the work of ten poets.

“And then there’s this,” Detective Morrison said, holding up a printed email. “Your life insurance policy on your mother-in-law. Half a million dollars. Taken out six months ago.”

“That’s legal,” Jessica whispered, voice gone paper thin.

“Legal to buy,” the detective said. “Illegal to collect when you’ve tried to provide the opportunity.”

I told the detective the truth: I’d watched the vial, watched the pour, switched the glasses like a magician switching fate, and waited. The arrests happened with the quiet efficiency of people who want to be home by lunch. They took Jessica first, and as they led her through my front door, cuffs catching the light, she looked back and hissed, “You have no idea what you’ve done.”

“I have an excellent idea,” I said. “You were about to find out the hard way.”

Michael sat on my sofa after they left, a demolition site where a son had been. “I didn’t know,” he said. “About the poison.”

“But you knew about the rest,” I said. “Sunset Manor. Dr. Steinberg. The power of attorney. Convince me you weren’t going to sign my money to yourselves because you could pretend it was love.”

“She said—” he began.

“Of course she did,” I said. “It is amazing what men will believe when it’s narrated by a pretty woman and ends in a check with their name on it.”

Then I asked for his phone and read the texts that made excuse unnecessary. “By Sunday she’ll be begging us to take care of her,” Jessica had written. “What’s Sunday?” Michael had replied. “Trust me,” Jessica had tapped back.

Trust evaporates on contact with sunlight.

I told him the power of attorney I’d given him was a fake. I told him the real money was strong inside trusts that didn’t care how sorry he sounded. I told him if he was convicted for conspiracy, the modest income stream I’d left him would vanish like foam.

“You destroyed my life,” he said finally.

“No,” I said. “Your choices did. I wrote them down in neat ink so a grown man would be able to read them.”

And then, because I am an old woman with a heart that still beats harder when her son cries, I added, “Your daughter will always have me. You might not, but she will.”

Part Two

The criminal justice system is not a thriller; it’s a conveyor belt. Jessica’s attorney tried to make her a victim of panic. The toxicology made her a perpetrator of planning. She took a deal: attempted murder, fifteen years. Michael’s attorney tried to make him a victim of love. The texts made him a conspirator. He took a deal: three years, five on probation, restitution ordered in numbers that made him flinch.

I did not wear black to the hearings. I wore navy. Navy is the color you wear when you intend to be taken seriously and want people to believe you will continue to live.

The day Michael was sentenced, Emma called me from her bedroom where the painted stars on the ceiling were flaking like dreams. “Grandma,” she whispered, “is Daddy going to jail because he’s bad?”

“No,” I said. “He’s going to jail because he did something bad.”

“Is that different?”

“It is,” I said. “It’s the difference that gives people a way out.”

She breathed into the phone. “Can I still come to your house on Saturday?”

“Yes,” I said. “And bring your swimsuit. The pool is warm and the rules are kind.”

We developed a rhythm, Emma and I. Saturday mornings meant pancakes and multiplication wrapped in admiration. Saturday afternoons meant swimming until we were both wrinkled and smelly of chlorine. Saturday evenings meant a movie where the old lady does not die and the child learns to fix a bike. Sometimes Jessica would text me and ask if “we” could have Emma for Sunday morning so she could “catch up on things.” I would say yes and remember that my boundaries were not a fence against a child.

Helen became my accomplice. We met for coffee every Tuesday and marveled that two women who had once chosen their daughters’ happiness over their own blood oxygen saturation could laugh so hard we cried. She told me she wanted to write a book. I told her I wanted to teach a class called “How Not To Get Eaten.” We made outlines. We shared receipts. We googled “oleander pruning” and called the city and asked them why a plant that can kill a grandmother in a party dress belongs on a median.

In March, Adult Protective Services asked me to speak on a panel about “Elder Autonomy and Family Pressure.” The moderator introduced me as “a survivor of financial exploitation” and I said, “I’m a survivor of good faith.” People nodded. I told them to write their wills while they were still angry at the right people. I told them to bake their bank managers cookies. I told them to carry their legal documents in their purses like passports. I told them to put a panic button under their desk and to tell no one but their lawyer. I looked out at a room full of women who had taught kindergarten for thirty years, who had raised sons who call only when the rent is due, and I thought, “The army of old women is coming. Tremble.”

David brought me peaches one afternoon and set them on my counter with a sigh of a man whose client is finally sleeping through the night. “One more thing,” he said. “The insurer is voiding Jessica’s policy given the conviction. Premiums refunded. Also, Burke’s strategy to use your husband’s other policy fizzled. The judge wasn’t fond of a defense based on ‘we only wanted to control her with paperwork, not poison.’”

“Judges have hobbies,” I said. “Some of them are justice.”

“What will you do with the money you wrestled back?” he asked, nodding at the ledger on my table where neat sums had become stories.

I pointed to three lines: an endowed scholarship in Emma’s name for girls at her public high school, continuing legal education funding for APS workers so they can recognize pretty lies in pearl earrings, and a grant to the nonprofit that drives old women to the bank.

“Leaving anything for yourself?” he asked.

“I bought a wagon,” I said. “For the plant store. And I hired a gardener because time is the only currency I believe in more than compound interest.”

Spring pressed on, and the roses went mad for the sun. I pruned them back with a ruthlessness I reserved for budgets. I thought about Frank some nights, but thinking about dead men won’t change a court order, and anyway, love and betrayal are both pregnancy tests—you are or you aren’t, and no amount of squinting makes the line different.

One Saturday at the pool, Emma asked, “Did Grandma Jessica try to kill you because she didn’t like you?”

“She tried to kill me because she liked money more,” I said, and watched her small face process a calculation grownups pretend to find complicated. “Do you like me more than money?” she asked.

“I like you more than almost everything,” I said, “including the good chocolate. But I will teach you to like yourself most. That way you can say no to a bad idea without having to call me first.”

We watched a little boy push a little girl in the shallow end. “Hey!” Emma yelled. “We don’t drown people where I come from.”

That night I wrote Emma a letter for her eighteenth birthday. It said, “Trust the lawyer who tells you the thing you don’t want to hear. Wear flats to court. Keep a copy of your signature on a piece of paper only you can find. Never let someone else’s sense of emergency turn into your permanent problem. If you ever feel afraid in your own kitchen, call me and then call the police. In either order.”

Jessica wrote me a long letter from the women’s facility where she now organized a book club and taught a yoga class in a room that used to be a chapel. She apologized for “bad decisions” and “panic” and said the word “money” three times in a row, and the word “murder” none. I wrote back, “I hope you are learning to breathe. Please make sure Emma knows how to make a broth. It’s an anchor when the ocean is ugly.” I did not forgive her, but I did not allow her to become a hobby.

Michael sent me a photo of his first pot roast. It was dry. I told him to tent the pan with foil next time and to stop opening the oven to watch things cook; some transformation requires trust and time. He got a second job stocking shelves overnight and learned that honest work with a sore back pays better in peace than stealing with a silk tie. He rang me up at the plant store once and looked at the roses and said, “Do they hurt you?” I said, “Not if you look where you put your hands.”

On the anniversary of the party, Helen and I stood in my kitchen and raised flutes—clean ones, from a clean bottle—and toasted to the year no one got away with it. “To old women,” she said. “The last surprise in a bad plan.”

“To girls who overhear things at the right moment,” I said, thinking of Emma coloring and whispering, “Grandma, today.”

“To lawyers with spines,” she added, and we both looked at David sitting on my stoop wiping peach juice from his chin with a linen handkerchief he pretends is not an affectation.

“To the security camera that made me feel like James Bond,” I said.

“And to you,” Helen finished. “For switching glasses.”

I laughed—sharp, unafraid, alive. “I learned to switch long before that. I switched the script. I switched the ending.”

When the sun went down, I took the wagon to the plant store with Emma and bought too many herbs. We planted them in the raised bed I had built with my own fury and my own two hands: basil for insistence, rosemary for remembering, thyme for patience. Emma chalked their names on little stakes in her careful printing.

“Which one makes you safe?” she asked.

“None of them,” I said. “I do. The papers do. The camera does. The boundary does.”

She nodded solemnly and watered the thyme until the dirt stopped drinking. “Okay,” she said. “Show me again where the panic button is. I want to be faster than last time.”

“We were fast enough,” I said, and pressed her hair out of her eyes. “But we can always be faster.”

We ate tomatoes on thick slices of bread and watched the sky take off its color by degrees.

A week later, I got a letter from Jessica in which she used my name without adjectives and asked if I would meet her in the visiting room with Emma. I said yes because love without wisdom is a gun with a hair trigger, and Emma deserves to see how to put a safety on it. We went. The air smelled like disinfectant and coffee. Jessica sat on one side of the table; Emma sat on mine. Jessica didn’t cry. She said, “I am sorry,” and let the period be the whole sentence. That’s worth something.

As we walked back to the car, Emma asked, “Is it over?”

“Yes,” I said. “No. Mostly. Enough.”

The thing they don’t tell you about happy endings is they still need groceries. You still have to change the battery in the beeping smoke detector at two a.m. You still have to say no on days when you would rather say yes because saying yes would get you an easier morning and an uglier life.

When I go to bed now, I check the deadbolt once. I put my hand on the panic button because habit is a religion I trust. I sleep. I do not dream of champagne.

If you were here with me, on the first step of the porch with a glass of decent merlot, watching my roses misbehave in the dark, I would tell you the moral that took me seventy years to earn: never be the most surprised person at your own party. Look hard at the hands that pour your drink. Write your plans in ink. Love your children, but do not trust them with your signature, your passwords, or your will. Give generously; lend almost never. Teach your granddaughter how to laugh at a thief’s surprise.

And if someone tries to poison you at your retirement party, smile, switch glasses, and let the chandelier make a thousand glittering knives you won’t ever need to use. The law is heavier than champagne. It will fall where you point.

END!

News

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. ch2

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. But… Part One…

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me. ch2

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… Part…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong. CH2

My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong Part One The roast…

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. CH2

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. Part One…

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… CH2

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… Part One The hallway outside my…

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One. CH2

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load